Update Summer 2018: After taking petitions, the FDA has denied approval for Isomaltooligosaccharide as a dietary fiber! See the video below for more details.

Video on the FDA's Denial over Isomaltooligosaccharide as a Fiber:

Isomaltooligosaccharides have been widely used in protein bars for a number of years for their high fiber, lower calorie claims, but they shouldn't be considered "dietary fiber" as the labels say.

Who doesn’t love a tasty protein bar?!

It’s high in protein, moderate in carbs and fats, and provides a healthy, satisfying snack that keeps you on track with your macros while still giving you the feeling of having something naughty.

The humble protein bar has come a long, long way since it was first introduced many years ago. Not only do they taste 1,000x better than the early generations of protein bars, but advancements in nutritional ingredients have led to the development of novel sweetening agents that help blunt the carb load of a bar, yet still provide the sweetness needed to deliver a phenomenal tasting product.

Of all the next-gen sweeteners that have debuted over the past few years, none has garnered quite the attention or widespread use as isomalto-oligosaccharide (IMO), a "prebiotic fiber" that's relatively sweet.

But is this stuff really a fiber as we typically understand it? Does it behave the same way? What is the caloric load and glycemic impact from it? These are the questions to be explored when considering IMOs in your diet.

TL;DR

- Isomaltooligosaccharide (IMO) is a lower-calorie sweetener used in protein bars, first popularized by Quest Nutrition's Quest Bars around 2010.

- Due to its structure, it's labeled as a "fiber", but we do not consider it a "fiber" in the classical dietary sense, and it should not be counted in your fiber numbers for those counting calories or watching fiber intake.

- The caloric load is estimated to be 2.7 - 3.3 calories per gram of material, a bit less than sugar and most other carbs, conferring some benefits for dieters (ie ~20 less calories per bar), but not as much as originally hoped.

- VitaFiber by BioNeutra is the most popular way to test it yourself - it comes in both syrup and powder forms.

- Oh Yeah! ONE Bars are our favorite protein bars containing IMOs. Quest Bars have since switched to soluble corn fiber.

- On the note of Quest Nutrition, we discuss the conclusion of the IMO lawsuit they faced over this ingredient and the marketing of their Quest Bars.

- Overall, it's still popular, but the market may be shifting away, as it's not as exciting as once hoped.

IMOs Up Close

IMOs gained notoriety as a moderately sweet carbohydrate (about 50-60% as sweet as sucrose[11]) that had a relatively high amount of dietary prebiotic fiber. Prebiotics are foods that stimulate and support the growth of beneficial microorganisms (i.e. bacteria) that promote well-being of the host (i.e. you!).[12] This makes for a carbohydrate that yields fewer “net carbohydrates” than more conventional sweetening agents. Additionally, it has a other properties such as low viscosity and moisture retention which make it extremely useful for inclusion in protein bars.

Typically, IMOs are added in excess of 15g, which lends a considerable amount of "fiber" to the bar's label, resulting in a bar with a low level of net carbohydrates and relatively low calories, at least as legally listed on the label. On top of that, IMOs are naturally occurring in foods such as honey, miso, and soy sauce.[1]

Consumers saw this as a big “win” as it not only offers the benefit of increasing their daily fiber intake, but it’s also “natural”, easing the concerns of those who have a phobia of artificial sweeteners in products.

However, there’s more than meets the eye with IMOs as the more you dig into the research, it might not be as calorie-free, fiber-rich as initially advertised.

IMO Sources

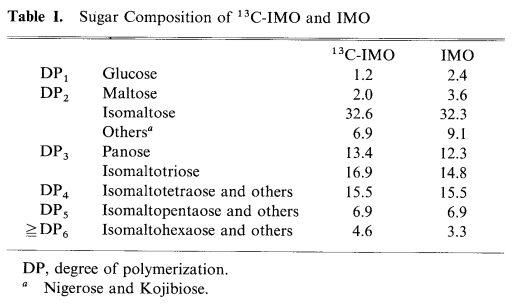

There’s a common misconception with IMOs, in that they are all sourced from one type of plant and contain only a single type of sugar. However, Goffin, et al. have shown that there exists a multitude of IMO including those produced from hydrolyzed starch but also:

- Koji-oligosaccharides

- Nigero-oligosaccharides

- gluco-oligosaccharides (branched IMO)

- cyclic IMOs

- Isomaltulose[1]

Why is this a big deal?

The fact is, these sugars are digested by various enzymes in the small intestine, some faster than others due to their particular structure.[13] This is significant because the whole original sales pitch of IMOs was their prolonged digestion in the body, which gave them the convenient classification of a “dietary fiber.”

However, different absorption rates mean some could be slow-digesting, while other may be faster digesting and not pass through the body in the “calorie-free” manner as was originally proposed.[5,6,7]

Remember this...we’ll come back to it later!

“Natural” Claims

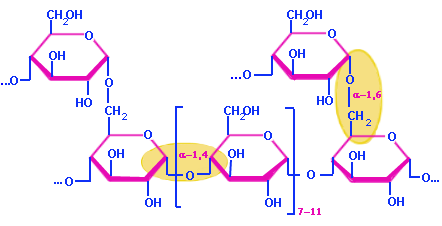

Here's a close up of an alpha 1,4 glycosidic bond with an alpha 1,6 glycosidic bond. Image courtesy TutorVista.com

IMOs do exist in nature, as described above, but what about the IMO syrup in your protein bars? How natural are they?

Simply put, it’s not economically savvy for companies to extract IMOs from foods on a widespread scale. IMO syrups used by manufacturers are produced via enzymatic reactions involving starch.[1]

These reactions convert starch into smaller glucose chains (2-4 units) that are connected primarily by ɑ-1,6, as well as other chemical bonds. So, while IMOs are indeed natural, as in "of nature", the ones in your bars aren’t as “natural” to the extent as some companies may claim. It will highly depend on the source used.

However, we're more concerned with the health impacts:

Are IMOs really a completely non-digestible dietary fiber?

In a word, no.

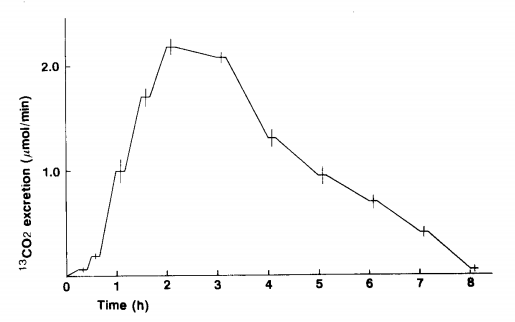

Fig. 1. Breath 13C02 Excretion of 6 Human Volunteers at Rest after

Oral Intake of 13C Labelled Isomaltooligosaccharides.[5]

Initial research, by Goffin et al., conducted with an in vitro digestive modeling system using either human saliva or hog pancreatic alpha-amylase documented an absence of IMO hydrolysis -- leading researchers to conclude IMOs may be a dietary fiber since it wasn’t hydrolyzed in the small intestine and reached the colon intact.[1]

However, the small intestine contains a number of brush border enzymes, sucrase-isomaltase among these, which has the ability to hydrolyze or “break down” the ɑ-1,6-glucosidic bonds mentioned above.[2]

So, there exists the very real and distinct possibility that the body is actually digesting these IMOs and they’re potentially not passing undigested to the colon.

For example, if you ate three IMO-based protein bars, you likely wouldn't experience the same situation as if you ate the equivalent amount of labeled fiber from something like wheat bran or psyllium husks.

The Down Low on Digestion

Several studies conducted involving rats, both in vitro and in situ, noted that IMOs were in fact digested in some fashion (i.e. they yield calories for the body).[3,4]

We know what you’re already thinking…. what about in humans?

Well, that’s been researched too!

-

Human Study #1

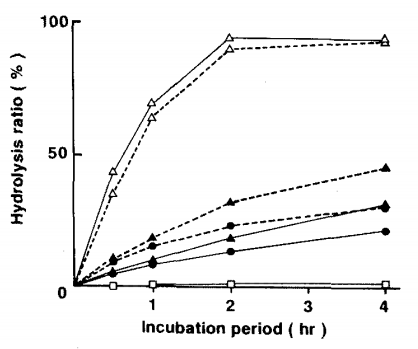

One study conducted in 1992 had subjects consume either 25g IMO syrup along with 50mg 13C-IMO (an isotopically-labeled form of IMO).[5] “Isotopically labeled” compounds are atoms with a detectable variation that can be tracked through a metabolic pathway or reaction. Including this 50mg isotope of IMO allows researchers to see exactly how the body metabolizes IMOs and where it goes.

Researchers investigated IMOs digestibility at both resting and exercise conditions. Under resting conditions, subjects' mean serum glucose levels were 109 mg/dL pre-ingestion and increased to a peak of 136 mg/dL at 30 min post-ingestion. Consummate with the glucose level increase, serum insulin levels also increased. Pre-IMO ingestion levels measured 4.8 μU/mL and peaked at 32 μU/mL at 30 min post-ingestion, up from pre-ingestion.

Researchers also measured Breath 13CO2 recovery -- measure of the metabolism of the isotopically-labeled IMO to carbon dioxide. Measurements were taken for 8 hours following IMO consumption and researchers noted that the IMO syrup had 83% that of an equivalent dose of maltose Breath Breath 13CO2 recovery. FYI, maltose is a completely digestible carbohydrate.

Following a brief exercise period, subjects had an IMO Breath 13CO2 recovery that was 69% of maltose. What we’re getting at here is that the study points to the fact that the majority of IMOs are indeed digested and metabolized by the body.

Researchers summarized their findings in the study as:

”These results indicated that a part of IMO was digested and the residual IMO was fermented by intestinal flora. The energy value of IMO might be about 75% of that of maltose.”[5] (emphasis ours)

-

Human Study #2

Another study conducted in humans had subjects consume either fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS), galactosyl-sucrose (GS) or IMO to measure any possible increase in breath hydrogen excretion.[6] The reason for using FOS and GS to compare to IMO is that both FOS and GS are non-digestible oligosaccharides.[6]

"Was that ~20 calorie savings and keeping the "sugar" number lower really worth it?"

Human cells do not readily produce hydrogen atoms; however, hydrogen can be produced when non-digestible (non-absorbable) carbs enter the upper GI tract and are then metabolized by bacteria of the colon.[7]

Both FOS and GS resulted in significantly larger breath hydrogen areas under the curve (14.2 and 8.5 times larger, respectively) than IMO.[6] What this means is that FOS and GS are much more non-digestible than IMO -- in laymen’s terms IMO is indeed digestible.Thus, while the breath hydrogen response to IMO was quantifiable, it was nowhere near as large as the breath hydrogen response to GS and FOS. In addition, neither a 10- nor 20-g dose of IMO caused appreciable gastrointestinal intolerance symptoms. This again indicates that the vast majority of the carbohydrate in IMO is, in fact, digestible.

”Notably, none of the subjects had abdominal symptoms after ingestion of 10, 20, or 40 g of IMO. These findings indicate that IMO is readily digested in the human intestine.”

Again, were you to try eating 2.5cups of oat bran fiber (providing 36g fiber - about half of it insoluble), the differences would be monumental...

Are they really Calorie-free?

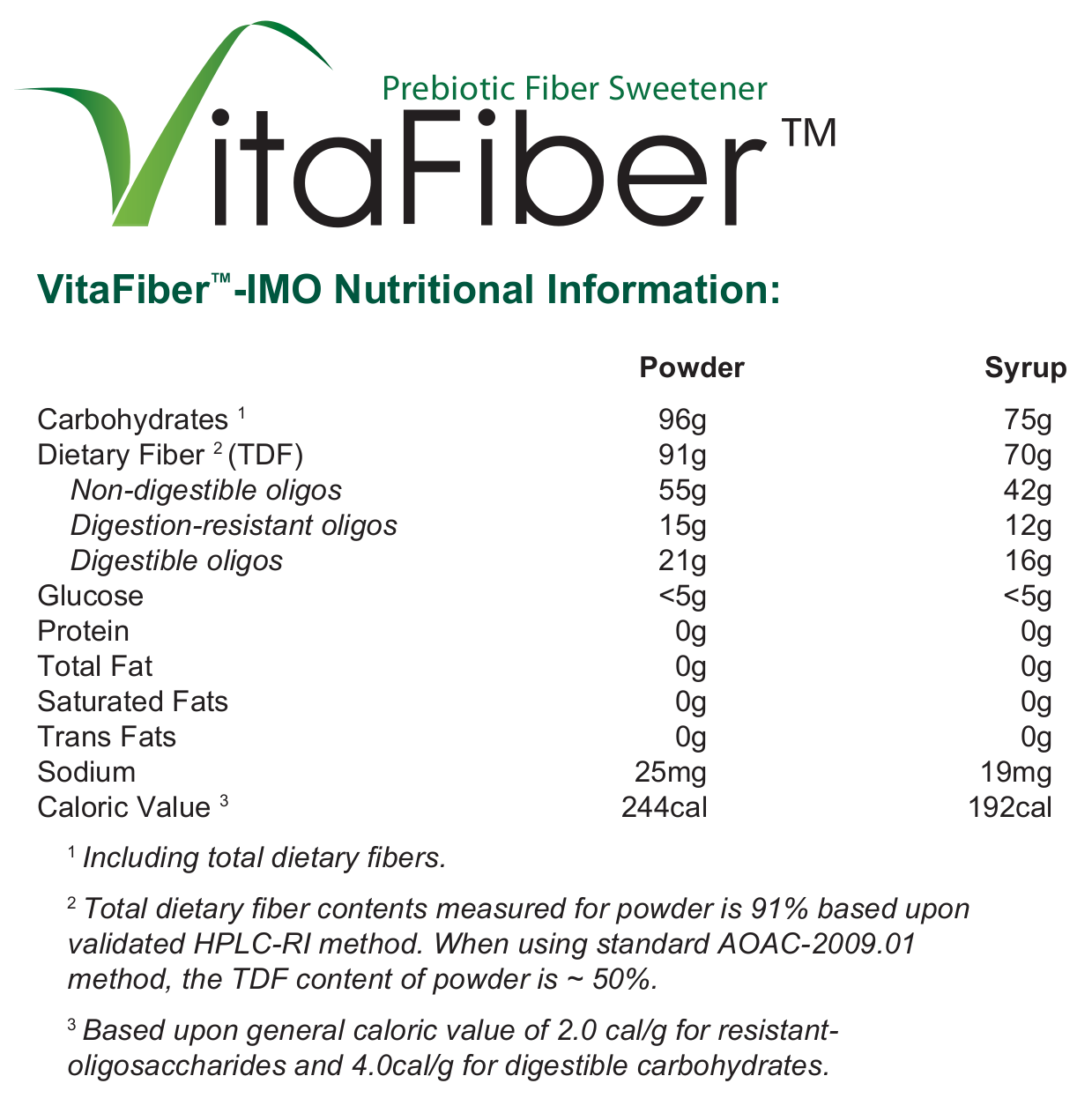

Courtesy BioNeutra, creators of VitaFiber, this is by far the best caloric breakdown you can understand from IMO Fiber.[14] This is from 100g worth of product.

Don’t bet your life on it!

Referencing the studies above, the first study showed IMOs had between having 69-83% the digestibility of maltose. Using these numbers to estimate IMO’s caloric impact and the energy density of maltose gives the following:

- Maltose energy density: 3.947kcal/g

- IMO energy density: 69-83% of maltose

- IMO energy density = ~2.7 to 3.3 kcal/g

Therefore, it’s flat out incorrect to assume or state that IMO carbs don’t count as carbohydrates or have any caloric impact simply because they’re classified as a dietary fiber.

Additionally, companies are also misleading consumers when the list the full carb content of IMOs are purely dietary fiber -- that’s just not the case.

IMOs Claim as a Prebiotic

One of the health benefits purported by IMO supporters is that it in addition to it being a dietary fiber, it also functions as a prebiotic. But, seeing how the “calorie-free” claims are less than solid, is the status of a prebiotic truthful?

It could be.

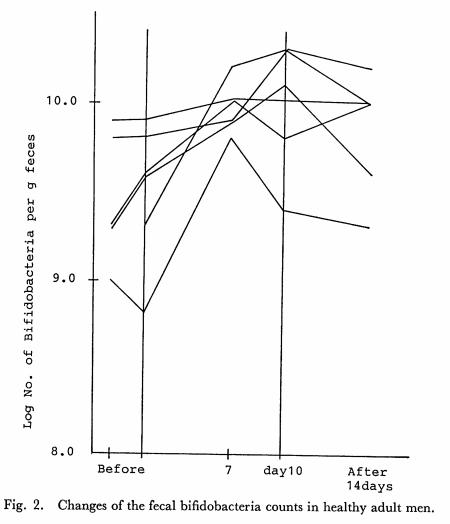

Although most of an IMO is digested prior to reaching the colon, some of the IMO is fermented by colonic bacteria. This fermentation increases some healthful bacteria populations, namely bifidobacteria:

A handful of studies have documented significantly increased fecal bifidobacteria concentrations when subjects ingested IMOs to the tune of 5-20 g/day for 12-14 consecutive days.[8,9] However, another more recent study found no evidence of prebiotic activity when subjects were fed 10g IMO for 7 consecutive days.[10]

So, IMOs may be a prebiotic -- at least from the small portion that escape digestion and undergo that colonic bacterial fermentation -- but its status as one is far from conclusive and probably shouldn't be used for any medical-grade purposes.

So how many calories is it?!

Ok, now that all of the mind-numbing science is out of the way, let’s see how to actually apply this when you’re reading a label that uses IMOs. Here, we’ll use the go-to IMO syrup all the top protein bar manufacturers use -- VitaFiber, made by BioNeutra.

BioNeutra is a Canadian manufacturer and supplier of various prebiotic and fiber ingredients / products. Most well-known of their line is Vita-Fiber.

According to the VitaFiber literature, the powder and the syrup have different calculations. 100g of syrup contains 75g of total carbohydrates, divided as follows:[14,15]

- 75g "carbohydrates"

- 70g "dietary fiber"

- 42g Non-Digestible oligos

- 12g Digestion-resistant oligos

- 16g Digestible oligos

- <5g glucose

- = 192 calories

How do we get that math?

- 42g Non-Digestible oligos have a general caloric value of 2.0cal/g* == 84 calories

- 12g Digestion-resistant oligos also have a caloric value of 2.0cal/g == 24 calories

- 16g Digestible oligos has a full carbohydrate caloric load of 4.0cal/g == 64 calories

- 5g glucose has a full carbohydrate caloric load of 4.0cal/g == 20 calories

- 84 + 24 + 64 + 20 = 192 calories total

* The current question is whether the portion of "Non-Digestible oligos" truly provide 84 calories. Are they labeled as 2.0cal/g because it's the law, or do you really get some energy from that portion? We've contacted BioNeutra and hope to have an answer soon.

100g of the powder, however, is far more dense, as it doesn't have liquid added, but the percent breakdown is the same. The VitaFiber liquid is easier to work with at home if making your own protein bars, but the manufacturers are probably using something similar to the powder and adding just the right amount of liquids for their needs.

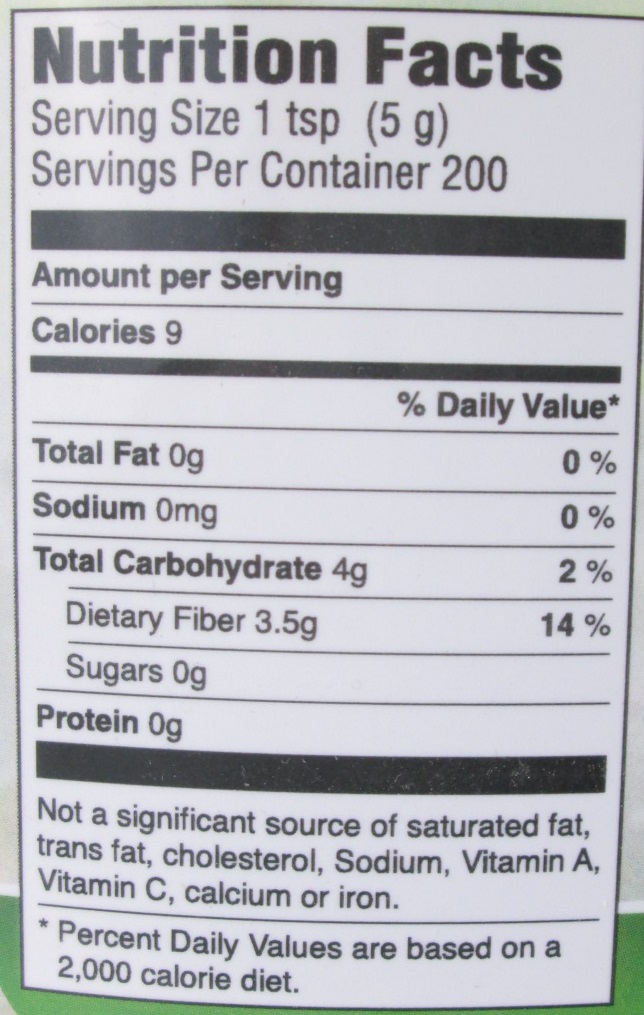

Now let's look at how that translates from a tsp of the liquid:

1 tsp of Vita-Fiber claims to be 9 calories, but when you do the math...you get 11 calories...what's up?

Each gram of carbohydrate yields 4 cal/g, while dietary fiber accounts for 2 cal/g.[14,15,16]

Putting the numbers together gives:

- Total Carbs = 4g

- Dietary Fiber = 2.5g

- Net Carbs = 1.5g

- Calories from Fiber = (2.5g) * 2 cal/g = 5

- Calories from other carbs = 1.5g * 4 cal/g = 6

- Total Calories = 5 + 6 = 11 calories / tsp of VitaFiber liquid

You’ve probably noticed that the ingredients panel says “9”, so what’s the discrepancy?

Nutrition Facts panels are rounded to the nearest gram for carbohydrates, fibers, and proteins (fats are different) when their mass is ≥ 1g.[17] So, theoretically, we could have anything between 3.5 to 4.49g carbohydrates, but the nearest whole gram is listed per FDA regulations, which gives us 4g total carbohydrates.

Point being, there is always “wiggle room” on a nutrition facts panel, regardless of the product, so at best, the Total Calories listed on an Facts panel is an estimate that could be slightly higher or lower than what’s listed.

Note: BioNeutra was contacted to assist with this article but never responded.

What happened in the Quest Nutrition Lawsuit of 2013?

The Quest Bar was the first bar to take IMO fiber to the mainstream market. In the early 2010s, Quest seemingly came out of nowhere to dominate the market, and while they're now using soluble corn fiber, earlier versions had labels stating "Isomalto-Oligosaccharides* (100% Natural Prebiotic Fiber)", with the footnote of "* Isomalto-Oligosaccharides Are 100% Natural Prebiotic Fibers Derived From Plant Sources."[18]

On that same label, the Apple Pie flavor of the bar had the following calories and macros:

- Calories: 170

- Fat: 5g

- Total Carbohydrates: 24g

- Dietary Fiber: 18g

- Sugars: 3g

- Protein: 20g

The classic mathematics of

[5g x 9cal/g (for fat)] + [6g x 4cal/g (for non-fiber carbs)] + [20 * 4cal/g (for protein)] + [18g * ~2cal/g (for fiber)] ~= 185 calories

(We assume some of the numbers were rounded down to arrive at 170 calories.)

However, this use of 18g of dietary fiber and the calories listed raised some questions, and eventually in September of 2013, a class action lawsuit was filed.[19]

In that suit, the Plaintiff claimed that the "Bars understated their calories by at least 20% and overstated their dietary fiber by more than 750%" based upon their testing and the generally-accepted methodologies for testing fiber.[19]

Sometime around the conclusion of this lawsuit, Quest Bars switched to soluble corn fiber, and these new Beyond Cereal Bars use the new allulose as their sweetener instead of IMO! A market shift occurring?

In this case, functional food technology (e.g. IMOs) had outpaced the FDA -- a not uncommon situation -- and there was really no officially agreed-upon method for determining the nutritional label specifications for IMOs!

To pile on and make matters worse, one blogger went so far as to [improperly] test the caloric value of Quest Bars,[20,21] falsely arriving at a calculation of 399 calories per 100g of material (since each bar is 60g and reported 170 calories, this lab test was insinuating that a 60g bar was showing 279.3 calories, not 170).

Quest's President and Co-Founder, Tom Bilyeu, then responded in a well-penned blog post titled "Are Quest Bars Too Good to Be True?",[22] stating that they welcomed lab tests, but "you will need to use a lab that is familiar with IMO testing", since "IMOs require a unique testing protocol specifically designed to accurately detect IMO".[23]

Those lab results and response posts are now all taken down, but thankfully, the Internet is forever and we still have access to them. Anyway, back to the lawsuit at hand:

Case stayed and then dismissed with prejudice…

The lawsuit was eventually stayed (halted) due to new developments at the FDA:

When the Complaint was filed in September 2013, the FDA had no regulations defining dietary fiber.

On March 3, 2014, the FDA officially published in Volume 79 of the Federal Register (at pages 11880 through 11987) a proposed Rule entitled “Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplements Facts Labels” (to be codified as an amended version of 21 CFR Part 101) whereby regulations for food labeling are to be revised. Among many other things, the proposed Rule defines dietary fiber for the first time, addresses how fiber should be measured, and mandates that companies using isolated fibers (such as IMO) submit citizen’s petitions to the FDA for it to determine if they are dietary fibers. The comment period closed on August 1, 2014.[24]

In the order, the Judge explains that courts can stay a case when there are regulations pending.

You can see that proposed 2014 rule cited by the judge here.[25]

Shortly thereafter, on October 6, 2014, the case was "settled" out of court,[26] with no settlement terms displayed. The case was then dismissed with prejudice, stating that the plaintiff had dropped the case, and that each party would have to pay its own legal fees.[27]

Even though it looks like they won the case, Quest Bars ended up switching to soluble corn fiber anyway, as explained in another blog post that has since been taken down but archives can be found.[28]

How does this help us?

The whole point of this section (besides updating interested readers on what ultimately happened) is that food technology often outpaces the FDA's abilities to regulate it, and cutting-edge consumers and companies can get caught in a gray area between nutritional knowledge and legal compliance.

With new food ingredients such as IMOs cerca 2010, there will be a period of time where we may not completely understand the true metabolic effects, or simply cannot agree on how the label should read because the law can be interpreted in several ways.

New ingredients aren't for conservative users or extreme dieters

In those cases, if you're a conservative consumer or are a very strict dieter, it's best to stay away from new ingredients until the research and regulations are both fleshed out. The last remaining question is whether that class action lawsuit helped move the regulation needle forward, or if it was just a big waste of time and taxpayer money.

All in all, we now know that the IMOs are a bit better than sugar in terms of calories, but still provide anywhere from 2.7 - 3.3 calories per gram of material. Was that ~20 calorie savings and keeping the "sugar" number lower really worth it?

Takeaway

Still feel as good about all those IMOs in your protein bar as you did before reading this?

New ingredients aren’t for conservative users or extreme dieters

Probably not, and sorry to burst your bubble, but the fact of the matter is that IMOs are comprised of carbohydrates that are digested by the human body and yield a caloric density of approximately 2.7-3.3 kcal/g.

While this is less than other sugars (~25% < maltose), you’re still experiencing a hit of carbs (and calories) that need to be taken into consideration when calculating your daily macros. So keep an eye out on IMOs and remember they’re not as jaw-dropping as originally touted, and don't let your calorie counting app fool you -- you still need to get some real fiber (both soluble and insoluble) in your diet, even if you do enjoy eating IMO-based bars!

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)