For PricePlow Formulator’s Corner #13, we tackle the challenge of creating a stimulant-based nootropic that boosts focus without disrupting sleep, using enfinity paraxanthine as the foundation.

Stimulants have their advantages. When you really need to buckle down and get work done – whether in the gym or while trying to meet a professional deadline – the default solution is typically some variation of caffeine.

The issue with caffeine (and other, more aggressive ingredients) is that while they can make you feel energetic for a short period, they also have negative effects, such as sleep disruption. Not only is it easy to consume too much and end up feeling jittery and "tired but wired", but excessive caffeine intake can profoundly impact your circadian rhythm, hampering your body's ability to repair itself.

The standard recommendation is to avoid caffeine after around midday to minimize its negative effects on sleep. That's all well and good, but what about when you need to dig deep in the afternoon and evening? Our latest Formulator's Corner segment seeks to answer just that as we put together a hypothetical focus supplement intended for use in the afternoons (and even at night) – without disrupting your sleep cycle.

Formulator’s Corner: enfinity-Powered Late Night Focus

The backbone of our formula is none other than enfinity paraxanthine from TSI Group. This relatively recent addition to the supplement mainstream is a total gamechanger. As one of caffeine's metabolites, it provides nearly all the focus-promoting benefits of caffeine without the jitters and anxiety, making it the perfect stimulant base for our nighttime formula.

Ideating a restorative stimulant-based nootropic

In addition to paraxanthine, we've included a variety of ingredients like tyrosine, creatine, theanine, and magnesium threonate, which create a truly restorative stimulant formula that will help you cram efficiently for your exams. This is also the first time we've seen anyone talk about combining enfinity with L-theanine, an amino acid known to be synergistic with caffeine. Will it work with paraxanthine as well? We believe it will.

Before diving in, subscribe to our TSI Group price alerts

Restorative Nootropic Formula Ingredients

-

Creatine - 3g

Creatine is well-known for its extensive array of studied benefits ranging from power output to lean mass gain. However, it also has nootropic benefits that are less widely recognized.

Neurons, like all cells, require ATP to function. During periods of high stress, disease, or injury, the depletion of ATP in neurons can lead to cognitive impairment. Research indicates that creatine supplementation might help replenish ATP levels in neurons, potentially reversing cognitive decline.[1]

A study based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), conducted between 2005 and 2012, found that individuals with the lowest creatine intake had nearly twice the risk of major depressive disorder (MDD) compared to those with the highest intake.[2]

Additionally, a 2018 review of six randomized controlled trials on creatine and cognition concluded that supplementation may improve short-term memory and reasoning skills, even in healthy individuals,[3] although further research is needed.

Our main point is this: there isn't enough creatine in nootropic supplements. So this is our way of saying that it should be included more often -- alongside enfinity, of course!

-

Tyrosine - 2g

If we're looking at a restorative nootropic that may be used at night, then there's a good chance we're going to be dealing with sleep deprivation. Enter L-Tyrosine.

L-tyrosine is a conditionally essential amino acid known to enhance focus, alertness, mood, and mental energy by increasing the production of key neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine.[4] These neurotransmitters are crucial for cell communication and play a central role in physiological processes. During high-stress events, such as intense exercise, neurotransmitter levels can become depleted, leading to decreased performance and fatigue. Supplementing with L-tyrosine before exercise may help prevent this depletion, supporting improved focus and endurance.

Norepinephrine and epinephrine are hormones involved in the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for initiating the fight-or-flight response during stressful situations. They help increase heart rate, blood glucose, and lipolysis, while dopamine is linked to feelings of pleasure, motivation, and mood.

By boosting dopamine levels, L-tyrosine improves cognitive function and helps the body better cope with stress. Research supports the use of L-tyrosine to enhance mental performance and assist in adapting to stressful conditions, including sleep deprivation in military experiments.[5,6]

-

Magnesium L-Threonate - 2g (yielding 144mg magnesium, 34% DV)

Magnesium plays a vital role in neurotransmitter production,[7] particularly in facilitating GABA signaling,[8] which helps promote relaxation and improve sleep quality. GABA, being an inhibitory neurotransmitter, counteracts the excitatory effects of glutamate, and both must be balanced for optimal cognitive and emotional health. Even a slight deficiency in magnesium can lead to sleep disorders and has been linked to a 22% increased risk of depression in people under 65.[9]

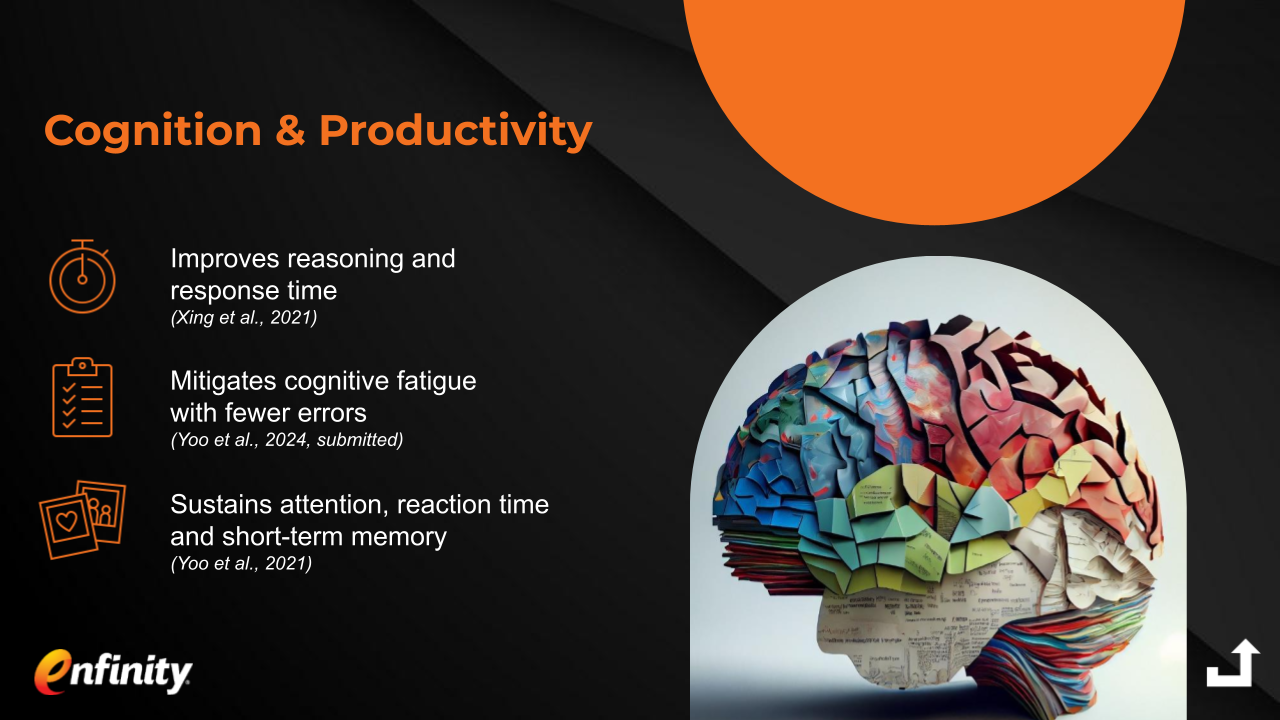

A new study finds paraxanthine (found in enfinity®) outperforms caffeine in boosting cognitive function after a 10k run.[10] Clear thinking under pressure is key to winning, and paraxanthine could be the edge you need.

Moreover, magnesium's ability to relieve muscle tension and promote relaxation has been observed in many individuals after their first dose, indicating the broad benefits of correcting even mild deficiencies.[11,12] Research, including meta-analyses and systematic reviews, shows magnesium's effectiveness in reducing anxiety and stress.[13] On the other hand, untreated magnesium deficiency may lead to more severe issues like chronic fatigue and heightened stress, making it crucial to maintain adequate levels for long-term mental and physical health.

Why magnesium threonate though?

Magnesium Threonate, specifically, is considered the nootropic form of magnesium, best used for brain function rather than more "bedtime" forms like magnesium glycinate. Magnesium threonate supplementation has been shown to increase neuroplasticity, cognition, and reduce cognitive impairment.[14-20]

Researchers now call it L-Threonic acid Magnesium salt (L-TAMS, formerly MgT), and have shown that it effectively enhance magnesium concentration in cerebrospinal fluid via oral intake.[14] It increases synapse density in the brain regions responsible for executive function and memory (namely the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus).

All in all, this is the clinically-studied "nootropic form of magnesium". But now it's time for the star of our show:

-

enfinity Paraxanthine - 150mg

Enfinity is the trademarked name for paraxanthine, a stimulant distributed by TSI Group Ltd that is used as a cleaner caffeine replacement.

Announced on September 1, 2023, TSI Group (the sponsor of this article) is the Exclusive Global Distributor of enfinity paraxanthine

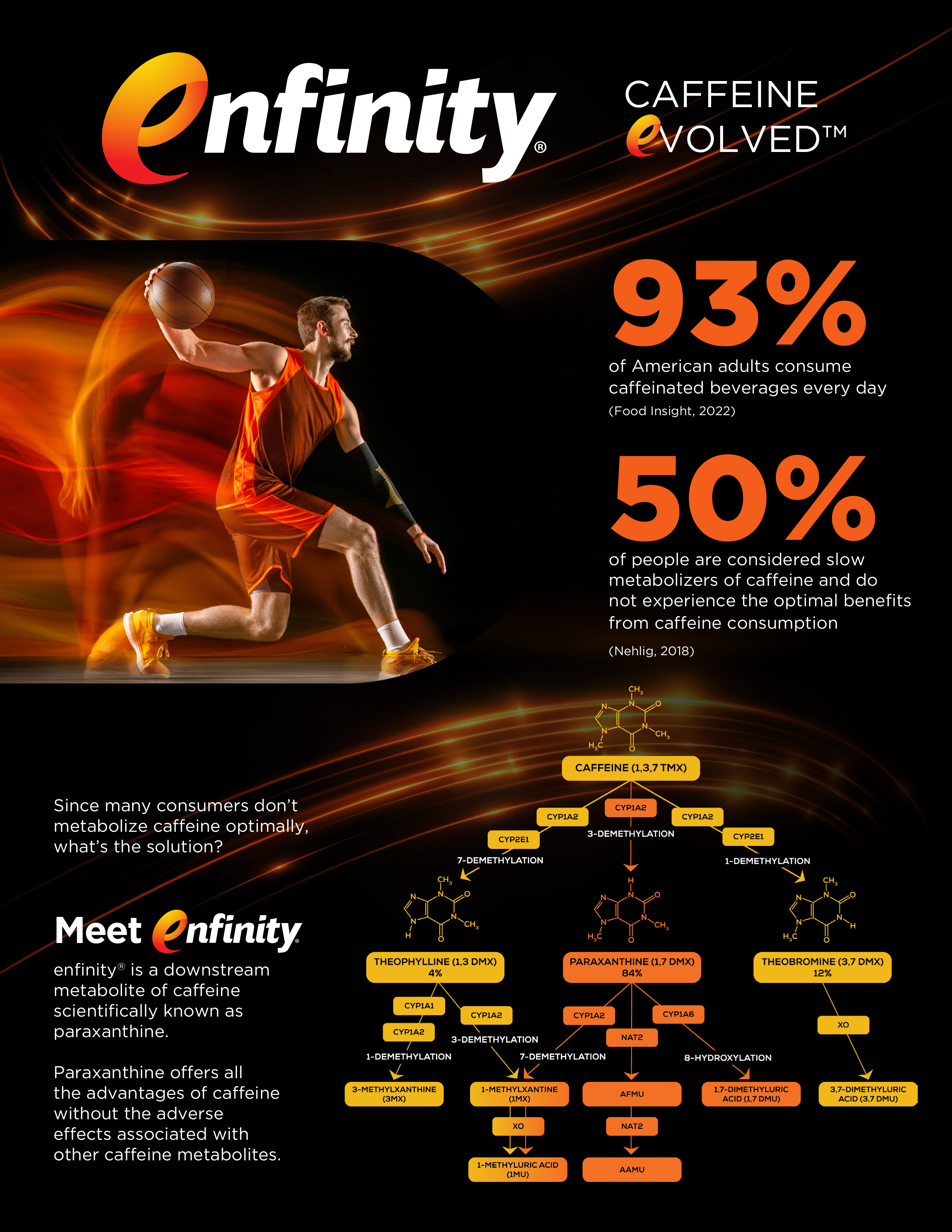

Paraxanthine is the primary metabolite of caffeine, responsible for most of caffeine's positive effects by blocking adenosine receptors, which promote wakefulness. When caffeine is consumed, about 70-80% of it is converted into paraxanthine,[21-23] while the remainder breaks down into two other metabolites, theophylline and theobromine, which have much longer half-lives and more undesirable side effects.[21]

By directly consuming paraxanthine (enfinity), users can bypass these less desirable byproducts and achieve a more efficient energy boost. This is the stimulant you want for an energized nootropic -- not caffeine!

Shorter half-life, smoother ride

One key advantage of paraxanthine over caffeine is its shorter half-life of 3.1 hours, compared to the longer-lasting effects of theophylline and theobromine, which can linger for over six hours and disrupt sleep.[21] Since caffeine metabolism varies based on genetics, with 54% of the population classified as slow or intermediate metabolizers, paraxanthine offers a more predictable and controlled stimulant experience for a wider range of individuals.[24-26] Slow metabolizers, in particular, are more susceptible to the negative side effects of caffeine's longer-lasting metabolites, making paraxanthine a more suitable option. Details on the genetic side of the story are covered in our article, "The Genetic Differences of Caffeine Metabolizers", which explains why we like using the MuscleTech EuphoriQ pre-workout for afternoon or even early-evening workouts.

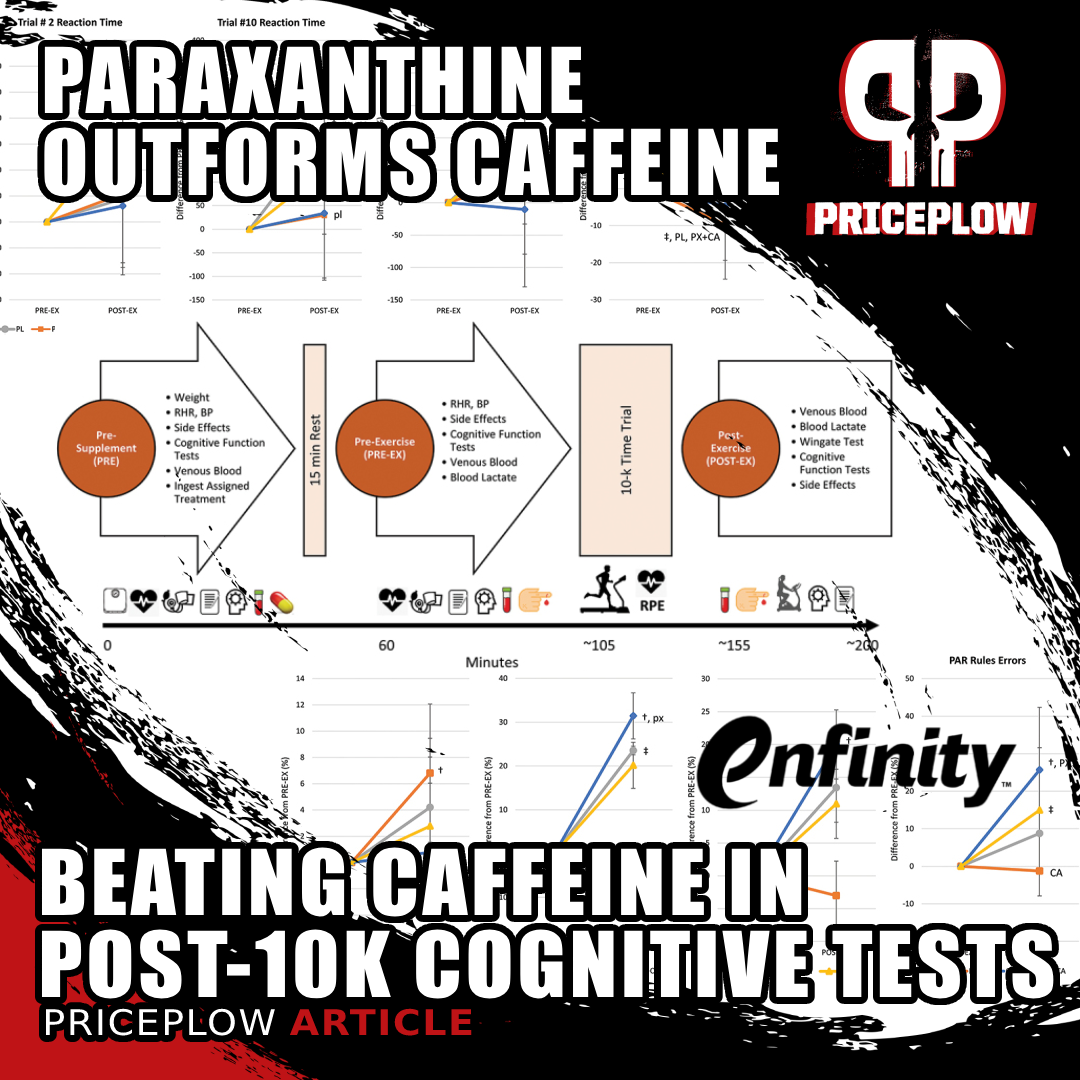

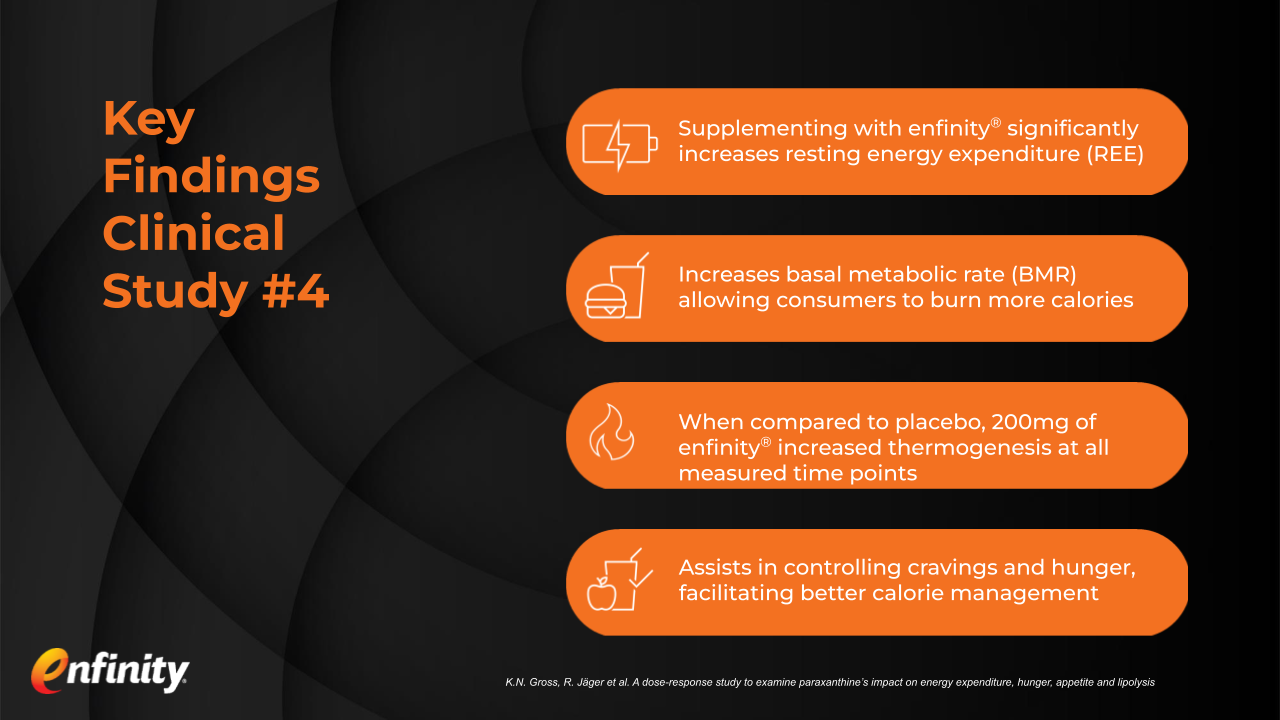

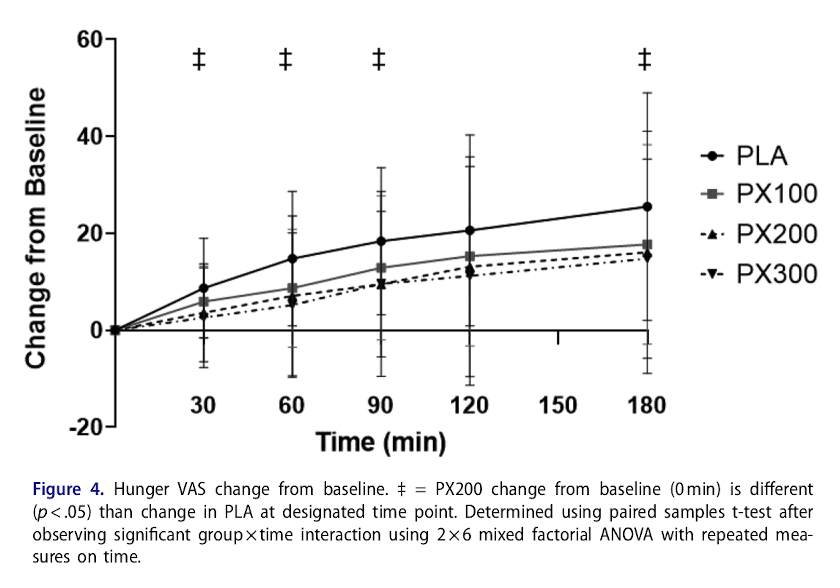

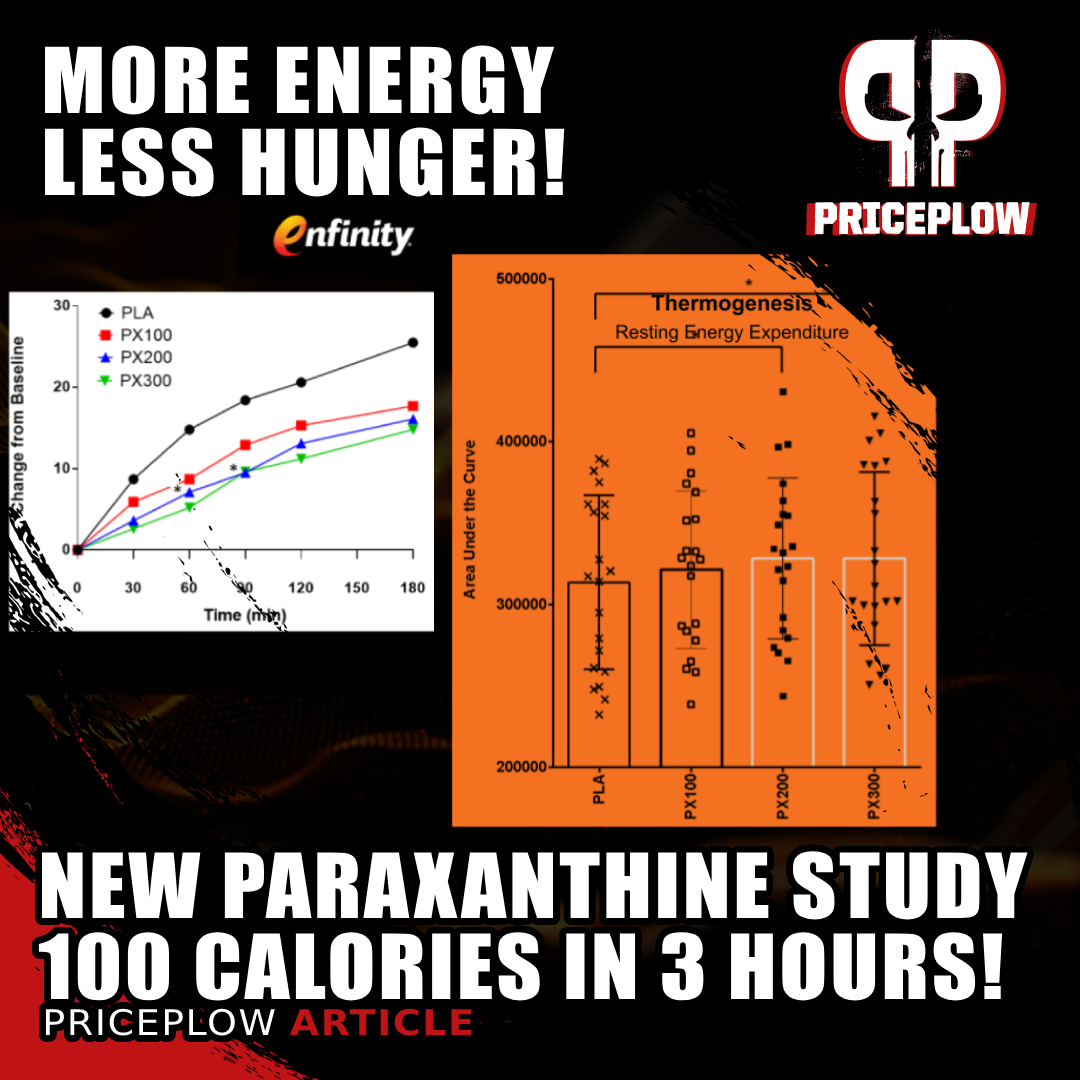

Area under the curve (AUC) analysis of the subjects' resting energy expenditure shows us that all doses of paraxanthine burned significantly more calories overall than the placebo.[27]

In addition to its shorter half-life, paraxanthine boasts other benefits. It binds more effectively to adenosine receptors, enhancing wakefulness, and unlike caffeine, it can enhance nitric oxide signaling,[28,29] which may improve circulation. Paraxanthine also supports dopamine production, protecting dopaminergic neurons and offering potential cognitive benefits.[28-30] Overall, paraxanthine provides a more consistent and efficient stimulant effect than caffeine, making it a superior alternative for many users.

New research on thermogenesis and cognitive performance

Since TSI Group began distributing enfinity, new research has come out that we've covered. First, a 2024 metabolic study shows that paraxanthine increases energy expenditure and reduces heart rate and hunger.[27]

More importantly for fans of nootropics, another study was published showing that paraxanthine outperforms caffeine in post-10k cognitive tests.[10] So if you're a bit wiped out, paraxanthine is the stimulant to consider.

We have a lot more information on this incredible stimulant -- for a great podcast, see Episode #072of the PricePlow Podcast with Raza Bashir and Shawn Wells. And for even more information, check out our main paraxanthine article.

-

L-Theanine - 75mg

L-Theanine is an amino acid that mimics the neurotransmitter GABA,[31] which has a calming effect on neurons by reducing excitability.[32-34] This results in decreased anxiety and promotes both mental and physical relaxation without causing sedation. Research shows that theanine can improve attention and reduce reaction time, especially in stressed individuals, helping them feel more focused and relaxed without feeling tired.[35]

Theanine is often used in conjunction with caffeine, where the two are synergistic for nootropic purposes, but thus far it has not been used with paraxanthine instead. We predict the combination would still provide a nice, smooth focus that doesn't feel jittery.

In our formula, we're opting for a 2:1 paraxanthine:theanine ratio, which we often like for caffeine-based supplements, although testing may determine that it should move down to 50 milligrams.

-

Zembrin (sceletium tortuosum extract [aerial parts]) - 25mg

Zembrin is a patented extract from kanna, which has been used in traditional South African medicine for centuries to enhance mood and relieve stress. Produced by PLT Health Solutions, Zembrin is the most thoroughly researched kanna extract, with numerous clinical studies validating its benefits for stress reduction, mood enhancement, and cognitive improvement.[36,37]

Its effects are primarily attributed to its rich profile of mesembrine alkaloids, which target serotonin reuptake and phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibition,[38,39] key mechanisms involved in emotional regulation and cognitive function.[40]

Paraxanthine (enfinity) significantly reduced hunger while increasing energy expenditure,[27] an incredible combination.

Zembrin's serotonin reuptake inhibition increases serotonin availability, improving mood and reducing anxiety. Additionally, PDE-4 inhibition enhances cognitive function by boosting cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, improving learning, memory, and mental clarity.[41] Studies have demonstrated Zembrin's ability to reduce the brain's response to stress, as seen in a 2013 fMRI study,[42] and its cognitive benefits were confirmed in a 2024 trial, where participants showed significant improvements in executive function and cognitive flexibility[38]. Zembrin's dual-action mechanism offers calmness without drowsiness, making it an ideal supplement for maintaining mental sharpness under pressure.

Next, for our vitamins and minerals, we're looking to restore critical components that are depleted by stress:

-

Folate (as Calcium Folinate) - 400mcg DFE (100% DV)

Folinic acid, a methylated version of folate (vitamin B9), is more effective than other folate forms. Folate deficiency can lead to serious health issues, particularly by increasing homocysteine levels, which can harm the cardiovascular system.[43] Many people have genetic mutations that impair the enzyme MTHFR, which is responsible for converting folic acid to 5-MTHF, making them more prone to folate deficiency.[44]

Supplementing with 5-MTHF bypasses this issue, and studies have shown it can boost plasma folate levels,[45,46] reduce homocysteine by 15%,[47] increase red blood cell folate content,[47] and support mood and cognitive health.[48,49]

With folate, we also like to provide its counterparts, methyl B12 and niacin.

-

Vitamin B12 (as methylcobalamin) - 2.4mcg (100% DV)

Methylcobalamin, the preferred form of vitamin B12, is a methylated compound that supports key metabolic processes by donating methyl groups.[50] Vitamin B12 is essential for red blood cell production, and a deficiency can lead to megaloblastic anemia,[51,52] where larger but fewer red blood cells reduce aerobic capacity. B12 also helps regulate homocysteine levels,[53-55] which is crucial for preventing birth defects and maintaining brain health.

Even mild B12 deficiencies can lead to memory problems and cerebral atrophy,[56] highlighting its importance in central nervous system function. While evidence on B12's ability to boost energy in non-deficient individuals is inconclusive, fatigue is an early sign of deficiency that can be prevented with moderate supplementation.[57]

-

Vitamin C - 90mg (100% DV)

Vitamin C is a well-known water-soluble vitamin found that serves as a powerful antioxidant that supports the immune system.[58] It's great for those purposes, but the reason we've added it here is because it's depleted in stressful situations, and supplementing it can attenuate increases in circulating cortisol.[59,60]

This isn't a massive dose, however. Remember, we're merely trying to restore what may get lost, not shut down the entire detoxification process here.

-

Niacin (as Nicotinic Acid) - 16 mg (100% DV)

Niacin in the form of nicotinic acid is added here -- this is the effective form that gives many individuals a flush at higher doses, which is why we're keeping it reasonable here with 16 milligrams. Niacin supports NAD+ production,[61-63] which is critical in supporting energy metabolism, DNA repair, liver detoxification processes, and much more.[64-67]

New research data has been published on enfinity (paraxanthine), showing increased energy expenditure compared to placebo (100 calories in 3 hours) -- yet it decreased appetite and heart rate![27]

This synergizes with the folate and B12 because NAD⁺ plays a vital role in the folate and methionine cycles by acting as a cofactor for enzymes like methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). The methylation reactions involved are critical for DNA synthesis, repair, and the regulation of gene expression. Vitamin B12 works closely with folate in the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, another NAD⁺-dependent process.

By boosting NAD⁺ levels through niacin supplementation, we enhance the efficiency of these interconnected pathways, supporting optimal methylation processes, reducing homocysteine levels, and promoting overall cellular health.

Other ingredients worth considering

This is one of the rare formulator's corners that we made reasonably affordable - the formula isn't completely blown out like many of our previous ones. However, if we wanted to include more of our favorite ingredients, we would consider the following:

- Cognizin Citicoline

- SalidroPure Salidroside

- MitoPrime L-Ergothioneine

- Acetyl L-Carnitine

However, for this round of ideation, we've kept it choline- and carnitine-free, although formulators can easily take the above ideas and run with them.

Somebody steal this formula, please

While this formula is strictly hypothetical, we hope someone steals it and makes it into a delicious afternoon energy nootropic powder. It's always difficult to decide if we should risk another cup of coffee late in the day, and this formula would make the decision a breeze. By using paraxanthine instead of caffeine, in addition to some synergistic ingredients like theanine and magnesium, we expect that this blend would result in an extraordinarily smooth, focused energy.

There's a reason paraxanthine is the cornerstone. The ingredient has, and continues to, open up entirely new worlds of formulation, and we'd love to see it in action in a formula like this. IT's an anti-stress stim-formula with restorative ingredients like folate, B12, and vitamin C, which are often depleted by stress -- and pre-powered by niacin. Perfect!

Be sure to sign up for our TSI Group news alerts below so that you don't miss out on the latest and greatest enfinity-based science:

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)