Everyone wants to be lean. Unfortunately, it's hard to kickstart the metabolism and feel good at the same time. Good news: these are the exact problems that ProSupps Thermo is here to help you solve, with some new ingredients to enhance the burn.

ProSupps Thermo Introduces NeuroRush and CapsiBurn from Aura Scientific!

ProSupps Thermo is a new fat burning powder that promises energy and appetite control with exciting new ingredients like CapsiBurn and NeuroRush from Aura Scientific!

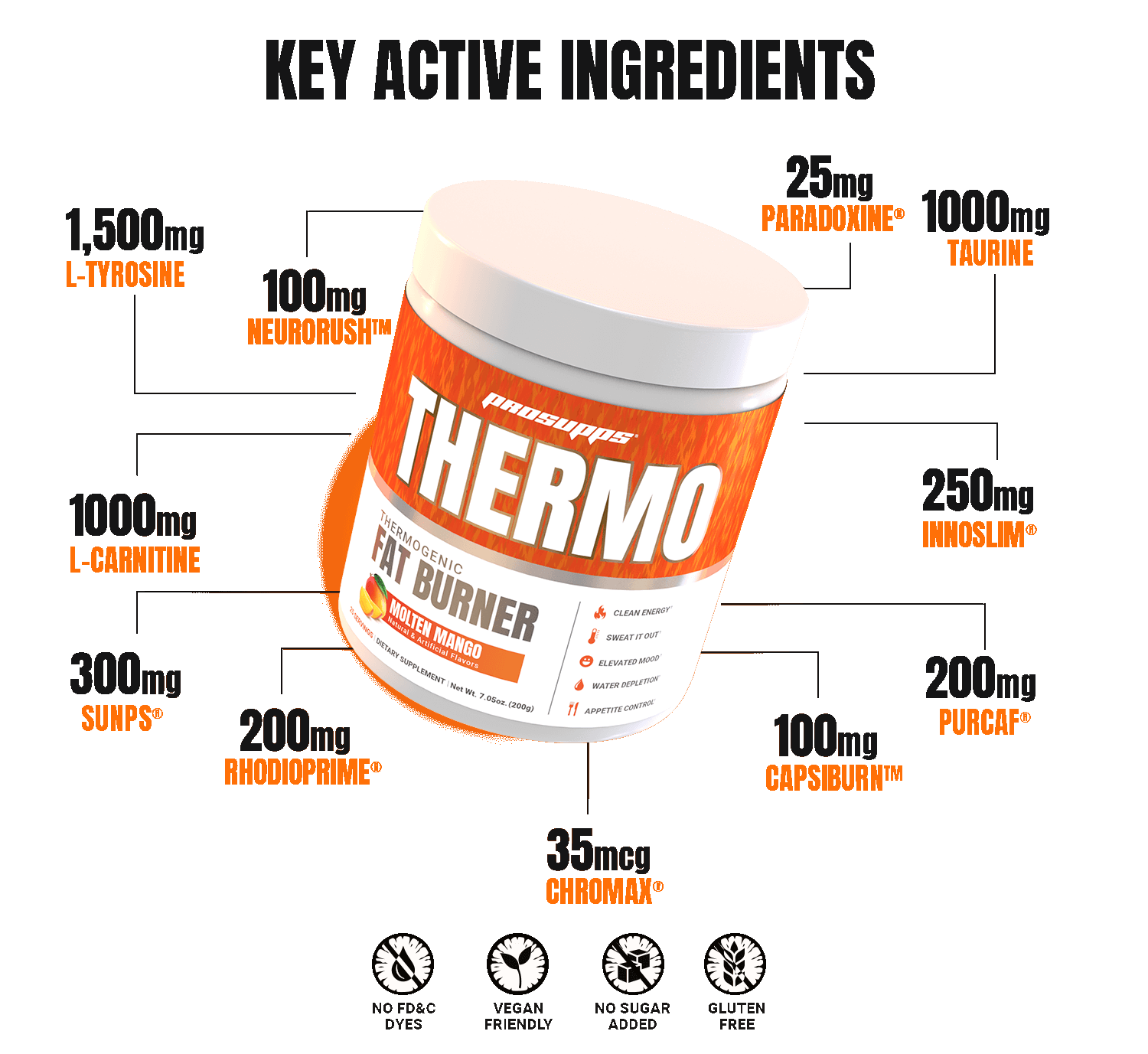

ProSupps Thermo is one of the most comprehensive fat-burning formulas we've seen in a while. It's a powdered drink formula touting thermogenic energy and appetite control, and with an 8-gram scoop, we have plenty of room inside.

A serious feel-good fat burner

This formula is loaded with all of the major fat burning ingredients in modern formulas -- especially some feel-good ones like tyrosine, taurine, acetyl L-carnitine, phosphatidylserine, and RhodioPrime 6X -- but there are two more in particular that we're most excited for: CapsiBurn and NeuroRush. Both of these are from upstart nutraceutical R&D firm Aura Scientific, and ProSupps Thermo is the first product to use both.

Aura has spent the last couple of years getting really deep into the research literature, finding studies and new delivery mechanisms for bioactive constituents to serve as the basis for new standardized extracts. And with these two ingredients, we think their efforts really paid off.

Let's get into how this works, but first, check PricePlow's pricing and availability and sign up for our Aura Scientific news alerts:

Pro Supps Thermo – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

ProSupps Thermo Ingredients

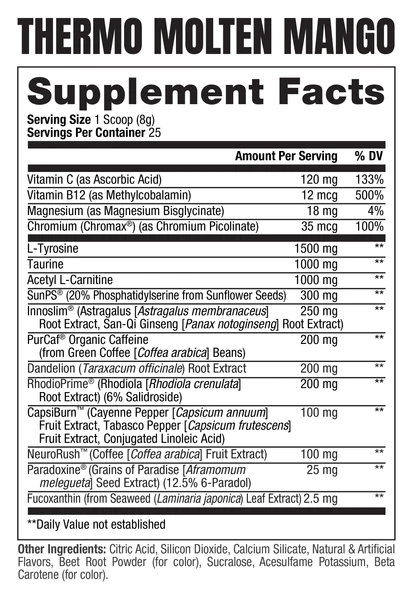

In a single 1-scoop (8 gram) serving of ProSupps Thermo, you get the following:

-

L-Tyrosine – 1,500 mg

The amino acid tyrosine is an excellent supplement for managing the stress associated with training and body recomposition. Tyrosine serves as a building block for catecholamine neurotransmitters such as dopamine, adrenaline, and noradrenaline,[1,2] which are crucial for regulating focus, motivation, and energy levels. Additionally, adrenaline and noradrenaline play a role in appetite suppression,[3] potentially making dietary restrictions more manageable.

Tyrosine can also increase the thyroid's production of hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4).[4,5] This matters because diet and exercise can interfere with the production of these hormones, especially when those behaviors are practiced simultaneously.[4,5]

Maintains Cognition During Sleep Deprivation

We all know that nothing can tank your physical performance—or your ability to build muscle—quite like sleep deprivation.

Not getting enough sleep can also severely impact your brain and compromise cognitive performance. However, tyrosine can help with this. Research conducted by the U.S. military indicates that tyrosine is better at restoring cognitive abilities in sleep-deprived individuals than caffeine.[6,7]

This is a good start for dieters - we love fat burning powders because you can simply hold more -- this alone would take up three capsules, and wouldn't have made the cut if we were taking capsules. Same idea applies for the next ingredient:

-

Taurine – 1,000 mg

Taurine is one of PricePlow's favorite jack-of-all-trades ingredients. This conditionally essential amino acid comes with a plethora of mental and physical benefits, for both health and performance.

Taurine can induce the browning of fat,[8] which is important because brown fat is more mitochondrial-dense and metabolically active!

We see taurine in endurance, hydration, and pre-workout supplements, and those use cases are covered below. But first, there's a fat burning mechanism at play too:

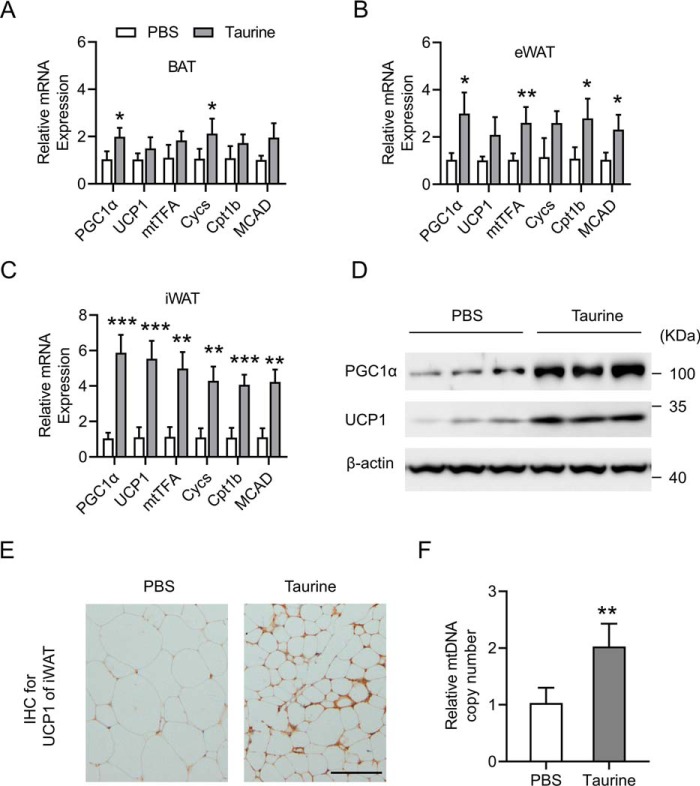

Supporting conversion of WAT to BAT

One of taurine's lesser-known benefits is the best reason to include it in a fat burning drink: it not only supports the process of non-shivering thermogenesis in brown fat tissue,[9] but also supports the conversion of white adipose tissue (WAT) to the more biologically active brown adipose tissue (BAT).[8]

Additionally, taurine can inhibit lipogenesis (new fat cell growth), yet leaves BAT growth unaffected while it does so.[10] It's also been demonstrated to reduce obesity-related hyperglycemia and inflammation.[11]

We don't always talk about these benefits in a pre-workout, hydration, or nootropic context, but they're important here. Now let's get to the other great reasons to use taurine:

Taurine for the mitochondria

Taurine is also a formidable antioxidant,[12,13] and is especially good for protecting all-important neuronal mitochondria from oxidative damage.[14] Taurine can even trigger the generation of new mitochondria in neurons, a process called mitochondrial biogenesis.[14] This is a big deal because, per Schoolhouse Rock, your mitochondria are the powerhouses of your cells – they generate all the power that your cells need to carry out essential functions.

In the brain, taurine acts like a neurotransmitter where it exerts calming, anti-anxiety effects.[15] It also decreases neural inflammation.[16] Simultaneously, taurine upregulates the synthesis and activity of dopamine, helping defend your dopaminergic neurons in particular, and helping increase their output.[17,18]

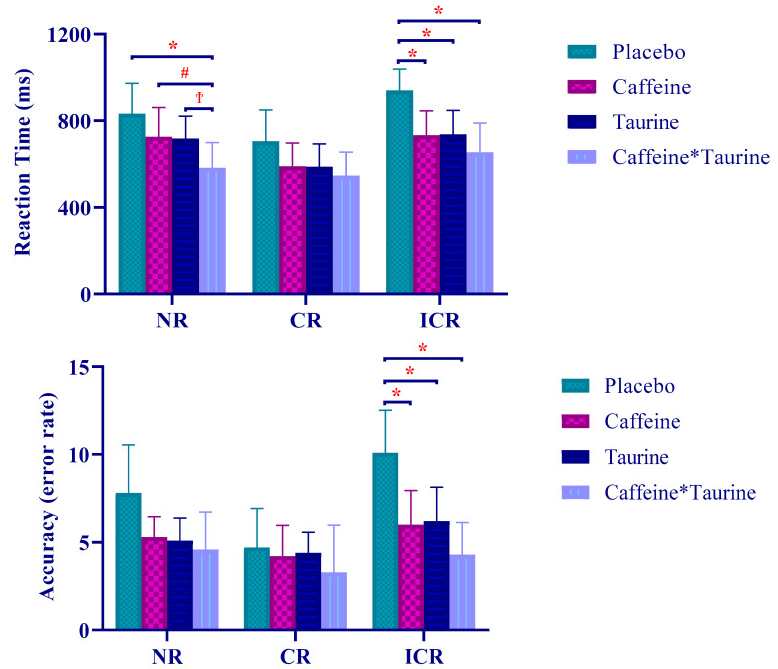

When it came to reaction time and mental accuracy, CAF*TAU absolutely crushed CAF, TAU, and the placebo.[19]

As you can see, taurine is neuroprotective via several different key mechanisms.

Caffeine synergy

We're especially pleased to see taurine in the ProSupps Thermo formula on account of the fact that it also contains 200 mg caffeine. As it turns out, caffeine and taurine synergize, as demonstrated by one study that found the pair increased performance in elite male boxers to a greater degree than either supplement on its own.[19]

Osmolyte

Taurine is also an osmolyte, meaning that it can positively affect the balance of fluid in and around your body's cells. More specifically, betaine can cause an influx of water into your cells, inducing a desirable state called cellular hyperhydration, which increases cellular resilience and access to nutrients.[20,21]

One 2018 meta-analysis showed that even a 1,000 mg dose of taurine, which is 50% less than the quantity used in ProSupps Thermo, can substantially boost athletic endurance.[22]

Taurine can also increase muscular electrolyte function[23] and help mitigate muscle cramping.[24]

-

Acetyl L-Carnitine – 1,000 mg

Acetyl L-carnitine (ALCAR) is a form of carnitine with pronounced neuroprotective, neurotrophic (i.e., promoting the growth and interconnection of neurons) properties. It's so good at defending the brain from oxidative stress and inflammation that it can actually cause significant reductions in mood disorders.[25]

The basic mechanism of action behind ALCAR, and all other forms of carnitine, is shuttling energy substrates like glucose and fatty acids into your mitochondria, which can then take up those substrates and turn them into adenosine triphosphate (ATP),[26] the energy currency of your body's cells.

For optimal health and function, all cells require a constant, reliable stream of ATP, which means that all kinds of cells can gain from carnitine's effects – especially neurons. What makes ALCAR special is its ability to traverse the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which enables it to be far more active in the central nervous system than other forms of carnitine.[27]

So, it isn't that ALCAR works better at the cellular level – rather, it is more bioavailable in the central nervous system, where it really counts.

Animal studies repeatedly show that ALCAR supplementation can significantly boost neuroplasticity, and accelerate learning.[28]

In one human study, conducted on patients over the age of 65 with mild cognitive impairment, daily ALCAR administration substantially boosted scores on a wide range of psychometric tests, compared to a placebo.[29]

Mood improvements

Other studies show an inverse correlation between serum carnitine and mood disorder risk. Moreover, the worse an individual's carnitine deficiency, the more severe his or her mood disorder is likely to be.[30] A 2018 meta-analysis showed that "ALC supplementation significantly decreases depressive symptoms compared with placebo/no intervention, while offering a comparable effect with that of established antidepressant agents with fewer adverse effects."[31]

The above three ingredients (as well as the next one) are all very supportive of mood and overall sense of well-being, and there's no way you could get them all in a product without using a powder. This is what makes ProSupps Thermo such a great fat burning drink. But the next ingredient's one we rarely see in fat burners:

-

SunPS (20% Phosphatidylserine from Sunflower Seeds) – 300 mg

Phosphatidylserine (PS) is a phospholipid, a type of lipid molecule that is a major component of cell membranes. Phospholipids are also required for the creation of myelin sheaths, a multi-layered complex of phospholipid bilayers that are interspersed with proteins and provide the structural integrity and electrical insulation needed for nerve fibers to function effectively.

If your body lacks access to phospholipids, then loss of nerve function can result, leading to neurodegeneration.[32]

On the other hand, peer-reviewed studies routinely demonstrate a negative correlation between PS intake and risk of neurological or psychiatric disorders.[33-36]

In the context of ProSupps Thermo, the most relevant benefit is that phosphatidylserine supplementation has adaptogenic and anxiolytic effects.[37] Large doses of PS can downregulate cortisol, your body's main stress hormone,[38] which can help you deal with the stress of training and cutting.

Under normal circumstances, the human body actually increases cortisol synthesis in response to physical training, and PS administration has been shown to dampen this rise in cortisol to such a degree that the phospholipid can actually increase athletic performance.[32,39,40]

-

InnoSlim (Astragalus [Astragalus membranaceus] Root Extract, San-Qi Ginseng [Panax notoginseng] Root Extract) – 250 mg

Innoslim is a patented combination of botanical extracts derived from Panax notoginseng root and Astragalus membranaceus root,[41-45] two plants often called by their colloquial names, Chinese ginseng and astragalus.

Both of these source plants are nutraceutical powerhouses that confer tons of health benefits, and contain such a broad spectrum of bioactive constituents that you can get very different effects from either extract, contingent on what specifically manufacturers standardize the extracts for.

When it comes to InnoSlim, the extracts have been designed to emphasize the thermogenic bioactive constituents of the source plants.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1)

InnoSlim downregulates a transporter protein called sodium-glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1),[46] which is responsible for helping glucose transit your intestinal wall. A decrease in SGLT1 expression significantly decreases the amount of glucose your body absorbs from ingested food – by as much as 41%.[46]

This represents a substantial reduction in effective caloric intake, which can help facilitate fat loss when paired with a caloric restriction program. Additionally, it means lower postprandial blood glucose levels, reduced de novo lipogenesis, and increased insulin sensitivity.

Glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4)

InnoSlim can also upregulate a different transporter protein called glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4).[47] Since GLUT4 is responsible for transporting glucose into muscle cells, increasing GLUT4 expression can also lower blood glucose levels, as glucose is moved from your blood into muscle.

Metabolism boost

InnoSlim can also increase your metabolic rate by upregulating key messengers like adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF).[48]

Additionally, it can upregulate adiponectin, an enzyme that limits glucose storage capacity in the liver.[49] In theory, preventing liver glucose overflow should significantly decrease your risk of contracting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

-

PurCaf Organic Caffeine (from Green Coffee [Coffea arabica] Beans) – 200 mg

Caffeine is a methylxanthine stimulant capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier,[50] a property that has a profound impact on the workings of the brain and central nervous system (CNS). PurCaf is an organic, naturally-sourced caffeine extract from green coffee beans.

As you're probably aware from personal experience, caffeine's exceptional CNS bioavailability makes it incredibly good at improving mood, sharpening focus, and increasing vigilance. Caffeine helps fight fatigue by downregulating your brain cells' receptors for adenosine, a nucleotide byproduct of ATP utilization that accumulates during the waking state, causing fatigue as it builds up.[51,52]

In the sports nutrition and fat-burning context of ProSupps Thermo, caffeine's effect on cellular metabolism is arguably its primary reason for inclusion. Caffeine downregulates phosphodiesterase (PDE). PDEs play a critical role in regulating the levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) within cells, thus controlling the duration and intensity of cAMP-mediated signaling pathways.[51-54]

cAMP-mediated signaling pathways have a significant impact on the cellular metabolic rate – you can think of it as your body's "need energy now" hormone. The increase in cellular energy created by caffeine's inhibition of phosphodiesterase can increase your overall caloric burn and multiple dimensions of athletic performance.

Among other things, cAMP signaling stimulates the breakdown of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. It also directly phosphorylates hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), thus increasing its activity and leading to the release of free fatty acids, which can be used as an energy source.[55,56]

Human studies consistently show that this mechanism can significantly accelerate lipolysis, the burning of stored fatty acids for energy.[57] In one study, the effect size was an impressive 50%.[58]

A 2020 meta-analysis, which included 19 different peer-reviewed studies, demonstrated that caffeine's ability to increase fat burning during exercise can be detected with doses as small as 3 mg/kg bodyweight.[59]

Other research has linked caffeine ingestion to improved performance in the athletic domains of strength, speed, power, and endurance.[51,53,57]

When you consider safety, cost, and effectiveness, caffeine is one of the most viable ergogenic aids on the supplement market.

Cognitive benefits

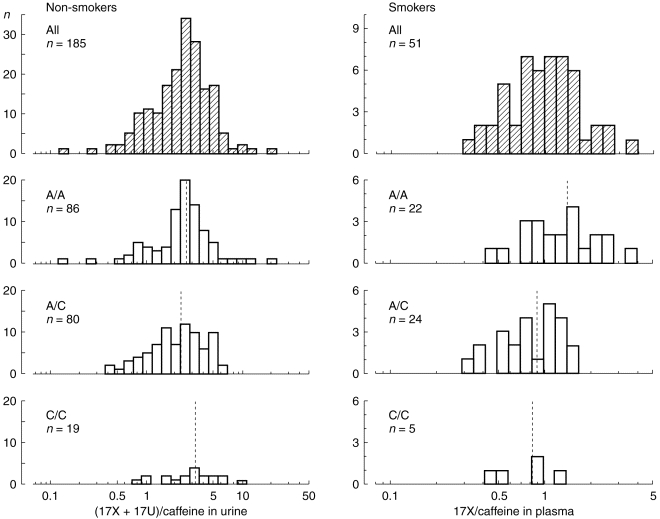

Are you a slow, medium, or fast caffeine metabolizer? In this study, ~46% of all participants were fast caffeine metabolizers (A/A),[60] meaning more than half of individuals aren't optimal caffeine consumers!

Caffeine can also improve cognitive performance, as it's been shown to improve attention, vigilance, and working memory, while speeding up reaction times.[61-63]

-

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Root Extract – 200 mg

Dandelion is a botanical diuretic.[64] In traditional folk medicine, it has long been used to improve bladder and kidney health.[64]

It's considered exceptionally safe thanks to the fact that, unlike the vast majority of diuretics, dandelion doesn't increase potassium elimination in the body.[65] This means you can use it to decrease water retention, without potentially compromising your body's electrolyte balance.

While not a fat burning ingredient, dandelion can definitely help you look leaner and more shredded by decreasing puffiness caused by water retention.

-

RhodioPrime (Rhodiola [Rhodiola crenulata] Root Extract) (6% Salidroside) – 200 mg

Rhodiola extracts are currently derived from one of two species – Rhodiola rosea and Rhodiola crenulata.

Those two varieties are nearly identical, except for one major difference: While both plants contain significant amounts of rosavin and salidroside, the crenulata plant contains vastly more salidroside than rosea does.[66,67]

Rosea owes its dominance to a long-standing belief that rosavin was primarily responsible for the benefits of Rhodiola supplementation. However, this belief has recently been challenged, thanks to emerging research that suggests salidroside may actually be more beneficial.[68,69]

Thus, the industry is gradually shifting from rosea-derived extracts to crenulata-derived extracts – and in order for this to work, we need a reliable, third-party-tested extract to serve as the industry standard.

Enter RhodioPrime from NNB nutrition

This crenulata-derived extract is standardized for an unheard-of 6% salidroside by weight, far beyond the 1% concentration that you can expect from rosea extracts.

Salidroside benefits

Two new studies on salidroside in Rhodiola have been published in 2023: Improved gut health and hormesis for longevity and neuroprotection

Peer-reviewed research shows that salidroside works to:

- Improve memory consolidation[67]

- Trigger autophagy, a process of cellular self-renewal[70]

- Improve cellular oxygen utilization[71]

- Upregulate the neurotransmitters dopamine, adrenaline, noradrenaline, and serotonin[68]

- Inhibit monoamine oxidase (MOA), an enzyme responsible for breaking down catecholamines[72]

- Upregulate neuropeptide Y[70]

By these mechanisms, salidroside supplementation can:

- Improve cognitive performance[67]

- Reduce feelings of anxiety and stress[73]

- Enhance mood[73]

- Mitigate depressive symptoms[74]

- Decrease mental and physical fatigue[75,76]

- Improve athletic performance[77]

- Decrease appetite[78]

- Improve glycemic control[79]

As you can imagine, RhodioPrime's popularity for fat-burning applications is going through the roof, thanks to its anti-cortisol, adaptogenic effects, which can help users deal with the stress of training and body recomposition.

Now it's time to get to the new stuff:

-

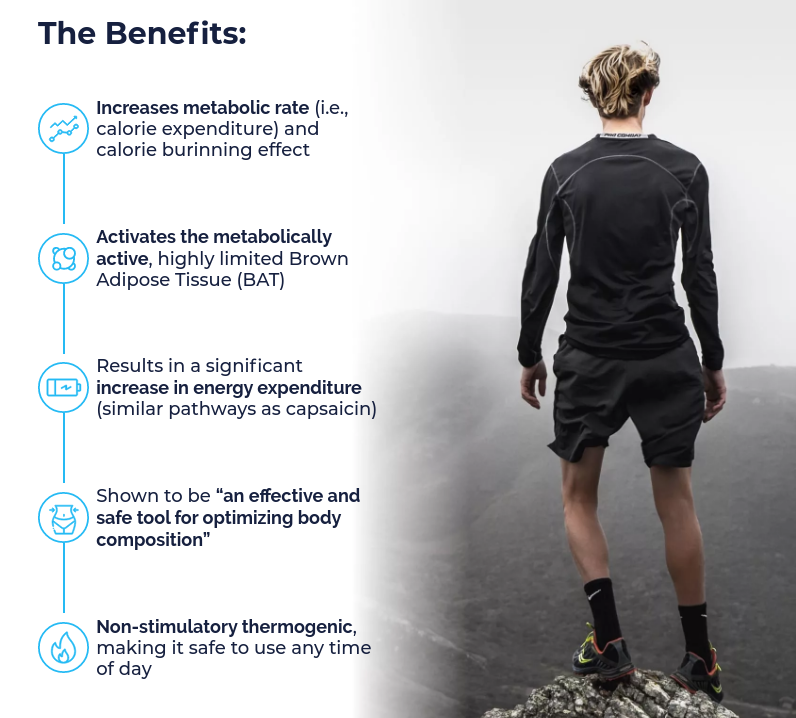

CapsiBurn (Cayenne Pepper [Capsicum annuum] Fruit Extract, Tabasco Pepper [Capsicum frutescens] Fruit Extract, Conjugated Linoleic Acid) – 100 mg

CapsiBurn is the novel red pepper extract from newcomers Aura Scientific, and it comes encased in a CLA lipid layer to protect both your taste buds and the manufacturer's machinery!

Taking a step back to the main constituent, capsaicin is an alkaloid derived from chili peppers, which is basically responsible for the burning and irritating sensation they're known for. It has a long history of use in supplements because of its lipolytic and thermogenic properties.[80] Capsaicin is also a good appetite suppressant,[81] so it can make fat loss easier by two complementary mechanisms.

A 2023 meta-analysis, looking at 15 different studies and 762 cumulative participants, concluded that:

"Compared with the control group, the supplementation of capsaicin resulted in significant reduction on BMI, body weight (BW), and waist circumference (WC). The current meta-analysis suggests that capsaicin supplementation may have rather modest effects in reducing BMI, BW and WC for overweight or obese individuals."[82]

Two earlier meta-analysis found that capsaicin supplementation can increase energy expenditure in overweight and obese subjects,[83] and can increase basal metabolic rate by increasing lipolysis, specifically.[84]

In fact, probably the most useful aspect of capsaicin is that it can keep your metabolic rate high while you're on a cut. One study showed that people who took 2.56 mg capsaicin with every meal did not experience the decrease in basal metabolic rate that's typical of caloric restriction.[85]

Another study found that just 6 milligrams of capsaicin per day, taken over a 90-day period, can cause a substantial drop in body fat.[86]

One really interesting thing about capsaicin is that it can downregulate pain receptors, thus increasing pain tolerance.[87] If you're particularly sensitive to the effect of capsaicinoids, this may enable you to push just a little bit harder during your toughest gym sessions.

What makes CapsiBurn special?

CapsiBurn is better than your generic capsaicin-standardized pepper extract, for two reasons:

- It uses both cayenne pepper fruit and tabasco pepper fruit extract. This supplies a broader spectrum of capsaicinoids, including dihydrocapsaicin.[88]

- The CapsiBurn molecules are encased in conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which should help buffer the capsaicin and decrease the risk of gastrointestinal upset compared to generic capsaicin.

CLA is often used in fat burners on its own, but there's not enough of a dose to make a huge metabolic difference. The key benefit is that it's lipid-encased but not with some nasty soybean fat.

Overall, dieters and manufacturers alike are excited about these benefits from CapsiBurn -- if we can get the thermogenic, appetite-suppressing benefits of red pepper extract with a bit less burn, we'll gladly take it.

The other Aura Scientific ingredient comes next:

-

NeuroRush (Coffee [Coffea arabica] Fruit Extract) – 100 mg

NeuroRush is a coffee fruit extract standardized to consist of 50% chlorogenic acids by weight, and also has and 5-caffeoylquinic acid. In our beta testing, we've found NeuroRush to be quite the feel-good ingredient -- it seems to add a bit more 'pop' to any stimulant it's paired with.

Given the impressively diverse array of health benefits linked to coffee consumption, you probably won't be too surprised to hear that coffee fruit extracts have a similar breadth. Generally, though, they're prized for their cognitive benefits.

Improved vigilance?! The mental energizing effects

One 2019 study found that just 100 mg of coffee fruit extract can partially prevent the decline in vigilance and rise in fatigue that people typically experience after completing a series of cognitively demanding tasks.[89] Interestingly, the "mental energizing" effect of the extract was the same at a 100-mg dose as at 300 mg.

Chlorogenic acid, cognitive performance, and mood

Other studies have found that chlorogenic acid, one of the key bioactive constituents in NeuroRush, can significantly improve cognitive performance and mood.[90-92]

Longevity considerations

A new novel ingredient developer named Aura Scientific has launched, with four new ingredients that include a feel-good coffeefruit extract named NeuroRush. Get the first peak here today!

One thing we don't always talk about with coffee fruit extracts is that there could be a longevity play here. Many people are aware of research showing that coffee drinkers, on average, live longer.[93-96] Well, animal research shows that coffee extracts may be a big part of these longevity benefits![97]

Coffee Fruit Extracts and Chlorogenic Acids: Well-Studied for Safety

One thing we love about coffee fruit extracts is that they're very safe, and there's plenty of excellent research demonstrating this.[98] And with respect to the chlorogenic acid inside, a massive review titled "The Biological Activity Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid and Its Applications in Food Industry: A Review" also goes heavily into the constituents supportive effects against free radicals and oxidative stress.[99]

What we also love is that ProSupps paired NeuroRush with PurCaf, so you're getting a real blend of natural botanicals in coffee -- far exceeding a supplement that would only contain synthetic caffeine.

You can definitely expect to see more NeuroRush coming out in the months and years ahead -- with this ingredient, Aura Scientific is taking coffee fruit extract to the next level.

-

Paradoxine (Grains of Paradise [Aframomum melegueta] Seed Extract) (12.5% 6-Paradol) – 25 mg

Grains of paradise extract is standardized for a bioactive constituent called 6-paradol, a phenolic ketone that is also found in ginger and greatly contributes to that root's characteristic tingly effect. Here we're going to find a lot of synergy with taurine:

Research shows that 6-paradol can help drive fat browning, a process in which new mitochondria get created in your body's white adipose tissue (WAT), thus converting it into brown adipose tissue (BAT). The reason this matters is that whereas WAT is metabolically inactive and doesn't burn any calories, BAT is metabolically active and does burn calories. BAT does this in a process called non-shivering thermogenesis (NST), which converts energy substrates like glucose and fatty acids into heat.[100]

Basically, with a greater ratio of BAT to WAT, the higher your potential daily energy expenditure.[101,102] We say potential because in order for this mechanism to work, cold exposure is generally required.

Besides burning calories and thus accelerating fat loss, NST can also cause immediate improvements to cardiometabolic health by burning up fatty acids and glucose from your bloodstream, thus lowering blood levels of both molecules.[103]

In one study, 19 healthy men aged 20 to 32 took a single 40-mg dose of grains of paradise extract, and the ensuing BAT activation caused their metabolic rate to go up significantly.[101]

A study in women found that grains of paradise can burn visceral fat,[102] an especially damaging type of fat that's closely linked to insulin resistance and diabetes.[104]

-

Fucoxanthin (from Seaweed (Laminaria japonica) Leaf Extract) – 2.5 mg

Fucoxanthin is a xanthophyll carotenoid that is abundant in seaweed. It's been shown to activate a transporter protein called glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) whose function is moving glucose from your bloodstream into muscle cells.

Thus, GLUT4 activity can help your body with glucose disposal – it stores carbohydrates in lean tissue, where you want them, instead of fat tissue, where they contribute to body fat gain over time.[105,106]

Fucoxanthin can also activate uncoupling protein 1 (UCP),[107-109] in WAT specifically,[110] which causes mitochondria to burn more calories as heat. So this is yet another ingredient that's support of the WAT to BAT conversion![110,111]

Research in animals has found that seaweed-rich diets, thanks to the fucoxanthin, can impair the development of adipocytes (fat cells) and augment the sensation of satiety.[112]

-

Chromium (Chromax) (as Chromium Picolinate) – 35 mcg (100% DV)

Chromax is a trademarked form of chromium picolinate made by Nutrition21. Since chromium picolinate is, according to the research, the most efficacious and bioavailable form of chromium available,[113,114] we love seeing it show up in ProSupps Thermo.

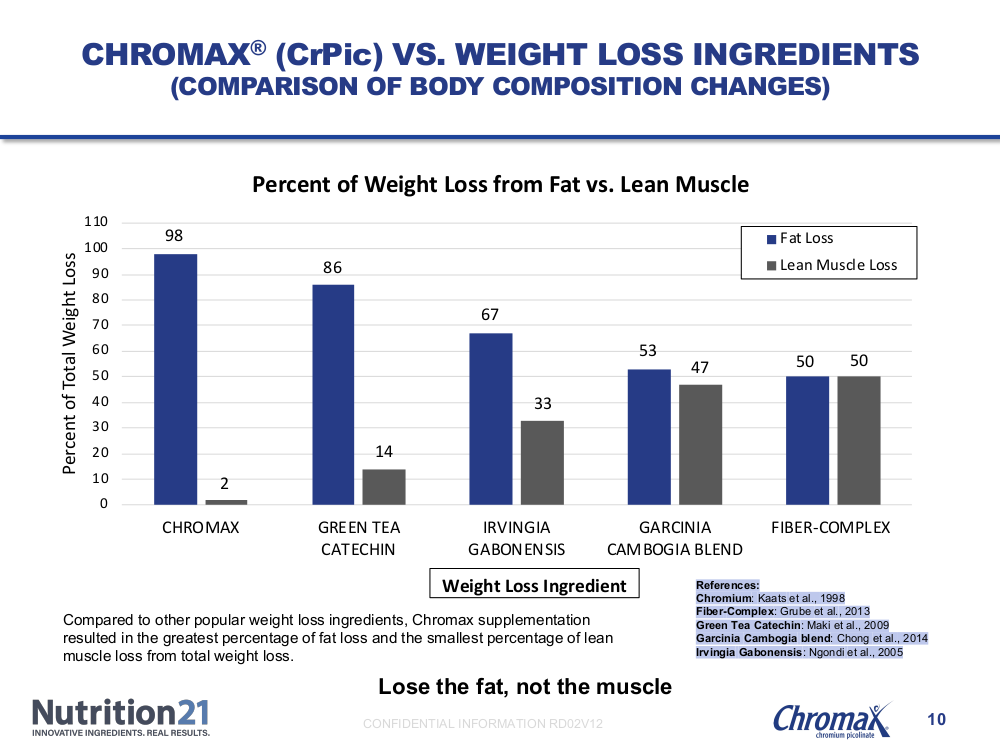

Compared to other popular stimulant-free weight loss ingredients, Chromax seems to outperform them all! Image courtesy Nutrition21.

Chromium works by magnifying the impact of insulin, thus enabling a more efficient cellular disposal of glucose.[115-117] In other words, chromium can increase insulin sensitivity – and as we've all heard by now, insulin sensitivity is one of the most crucial factors in maintaining long-term metabolic function.[118]

-

Other Ingredients

Plus, ProSupps Thermo has some nice vitamin and mineral support:

-

Vitamin C (as Ascorbic Acid) – 120 mg (133% DV)

-

Vitamin B12 (as Methylcobalamin) — 12 mcg (500% DV)

-

Magnesium (as Magnesium Bisglycinate) — 18 mg (4% DV)

While this isn't a monstrous amount of magnesium, we'll take any amount of magnesium glycinate, almost any time.

-

Flavors Available

Conclusion: A feel-good, WAT-to-BAT machine with 2 Novel Ingredients

ProSupps Thermo is an absolutely loaded thermogenic fat loss formula. Building a powdered fat burner supplement allows companies to do so much more than they can with capsules - you don't have to choose between taurine or tyrosine or carnitine -- you can do all of them!

But what really makes it stand out are rising star ingredients, CapsiBurn and NeuroRush. Aura Scientific has done some really amazing R&D on these two, and we're really looking forward to seeing the results of ingredient-specific clinical trials published on these ingredients. This is your first chance to try the new duo, so it's definitely worth a test:

Pro Supps Thermo – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)