Regular readers of the PricePlow blog see us harp on mitochondrial health and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production on at least a weekly basis, if not more frequently.

We emphasize it for the same reason that the supplement industry as a whole is focusing more and more on mitochondrial optimization and ATP generation: cellular energy and bioenergetics are fundamental to every aspect of human health and performance.

ATP’s Manifold Importance

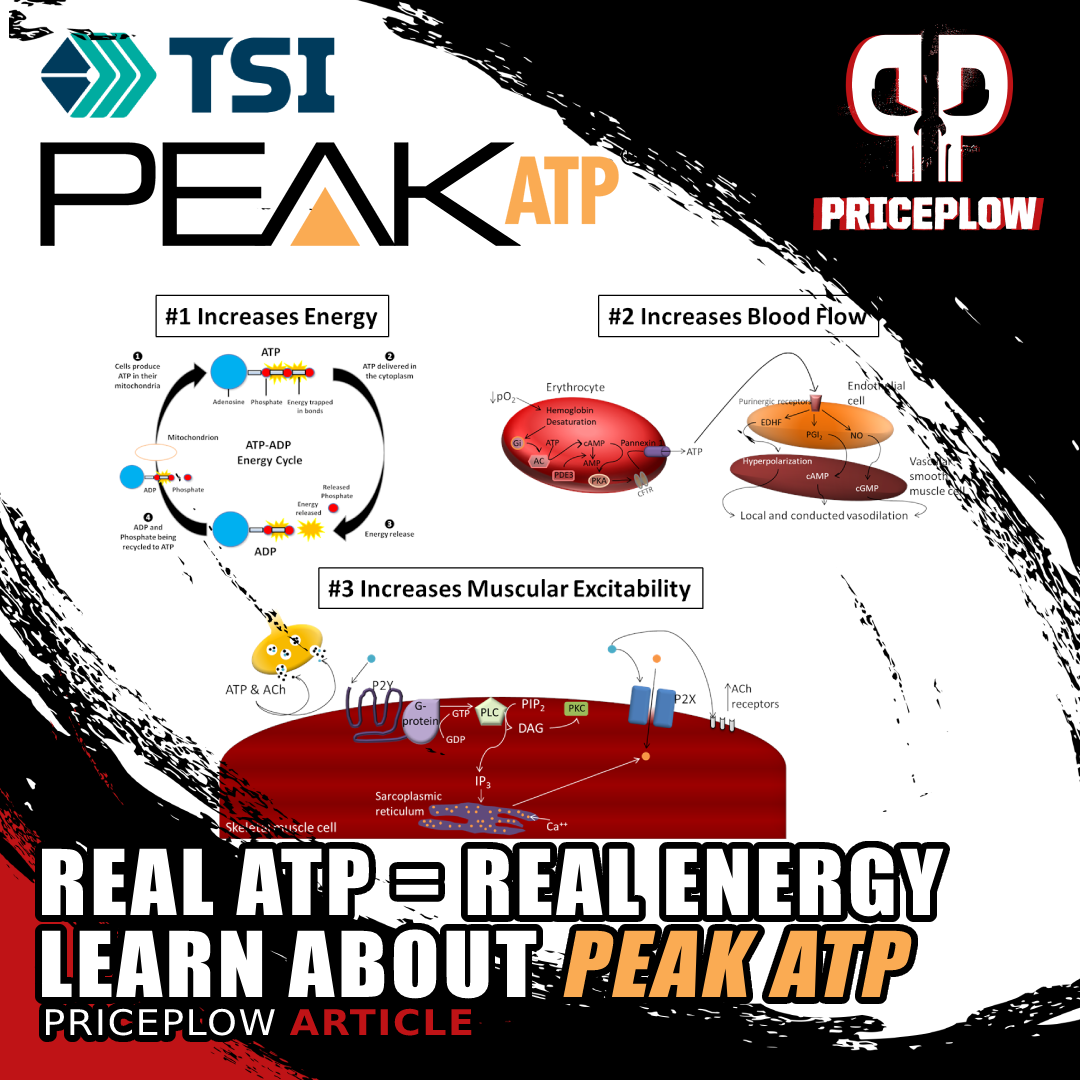

Peak ATP is a patented oral ATP supplement that's been shown to increase blood flow, boost muscle activation through calcium release, and help boost muscle mass, strength, and recovery. This article covers the biochemistry, mechanism, and human research in detail.

Let's consider creatine and caffeine. Two incredibly common dietary supplement ingredients that most of us have used, or even use on a daily basis. Creatine is a "bodybuilder supplement" – in most people's minds, its purpose is to build muscle. It has many uses, but it's primarily used because it can improve cellular energy production, in the form of ATP.[1]

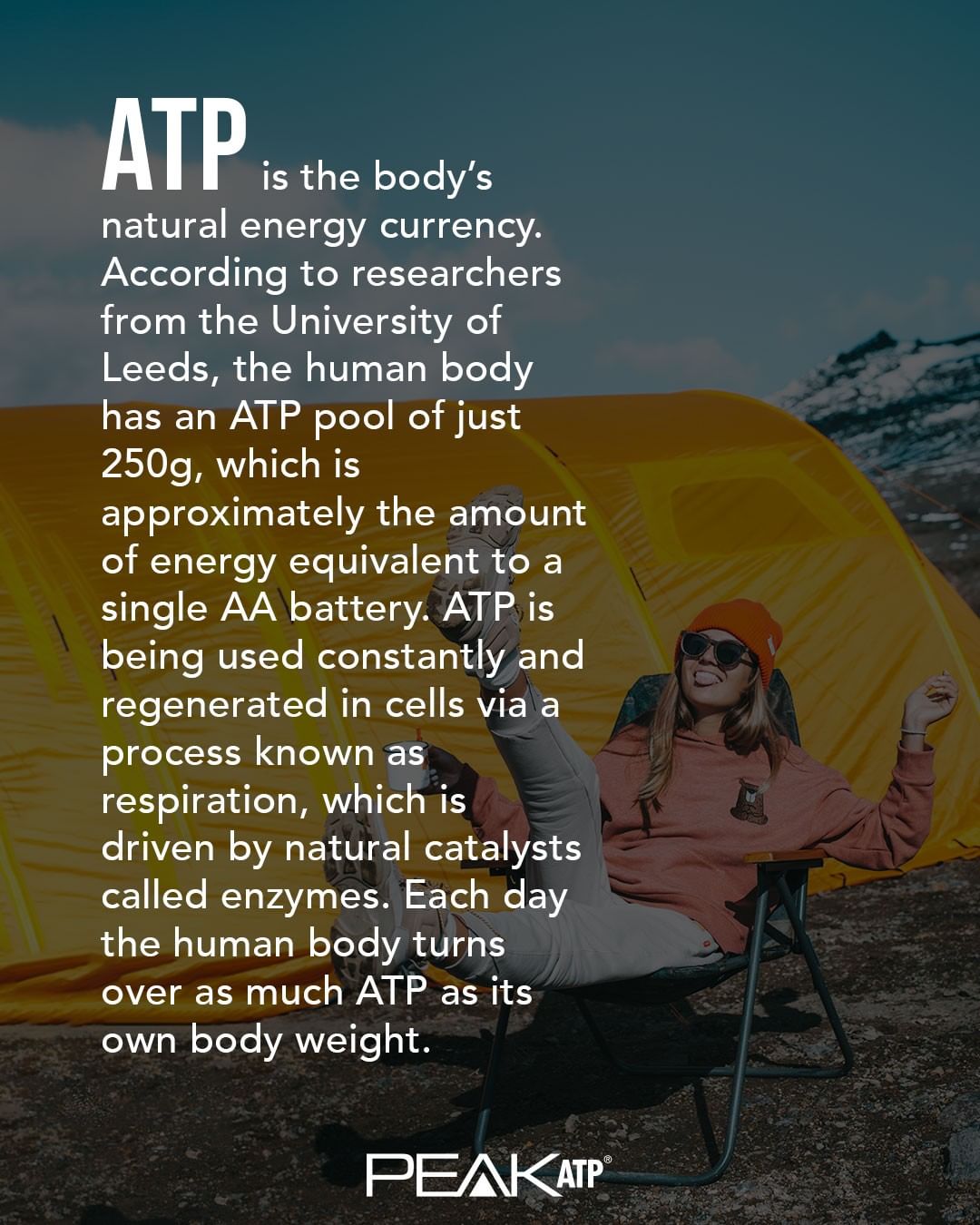

Normally when we think of energy supplements, caffeine comes to mind. However, realize that caffeine doesn't boost ATP, but instead binds to adenosine receptors,[2] which are normally used to regulate neurotransmitter release. Instead of giving energy, caffeine merely prevents you from realizing you're low on energy!

With improved ATP production from creatine or an improved diet, we can see numerous benefits, which makes sense given the molecule's global importance for human health and energy.

But it's not just health we're interested in -- it's performance. Which leads us to an issue:

The Problem: ATP Levels Drop During Exercise

Ingredients like creatine don't raise ATP levels directly. Instead, it acts to help readily synthesize ATP. For example, creatine doesn't contain ATP, but helps support ATP production by increasing your body's stores of phosphocreatine, which is a storage depot for high energy phosphate to supply for synthesis of ATP.

In the supplement industry, this has been the go-to strategy for as long as manufacturers have been interested in developing ATP boosters - increase ATP production by supplying the necessary precursors for it. There's a catch, though.

Creatine takes time, but we need ATP now

Using creatine and eating creatine-containing foods is a great strategy, but it's not acute. It takes time to build up to saturation levels, meaning its role in ATP metabolism won't be instantly deployed.

And the immediate issue is that ATP levels drop during exercise as the ATP is consumed.[3,4] And, as we'll explore throughout this article, ATP is a molecule responsible for the release of nitric oxide, leading to improved blood flow! We often discuss nitric oxide in the sports supplement industry, but don't fully understand how ATP is involved.

Thankfully, if we want to replenish ATP and keep levels high during hard training, there's a more acute way to restore levels and keep them elevated so that we can reap its countless benefits:

The Solution: Peak ATP!

Here's where Peak ATP from TSI Group Ltd (TSI Group) comes in.

This is the patented oral ATP supplement[5-7] with significant performance benefits, and we couldn't be more excited about it after exploring how it works. And one of the incredible properties is that it works acutely.

After all, if ATP is so great for exercise performance, but it's declining as we use it, then why not just supplement more of it directly.

As we'll learn in this article, it actually functions as a concentrated blood flow ingredient, yet only requires 400 milligrams to get a clinically-effective dose. That's a small capsule's worth!

Peak ATP: ATP disodium for max stability and solubility

So why is this the case? According to a systematic review on ATP disodium that was published in March 2021, the researchers found over ten different studies where oral ATP disodium supplementation was shown in randomized controlled trials to have significant benefits for health and athletic performance.[8]

Further studies have shown, and have repeatedly validated in a clinical setting, that with the Peak ATP formulation of ATP disodium, can raise ATP concentrations in the human body during exercise.[9]

As we continue, we'll look at studies using Peak ATP to improve performance, and then get into some popular products that contain it (a couple of great recent examples are Alpha Prime Supps' Legacy Pre-Workout and Beyond Raw's Concept X). You can also sign up for our Peak ATP and TSI Group news alerts to get notified when we have new products, news, and studies to announce:

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

ATP: A Detailed Look at the Biochemistry

If you read the PricePlow Blog, or any other publication that discusses the biochemistry behind supplements, you've no doubt heard a million times that mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell, and that ATP is the body's energy currency.

But how exactly does ATP deliver energy to cells?

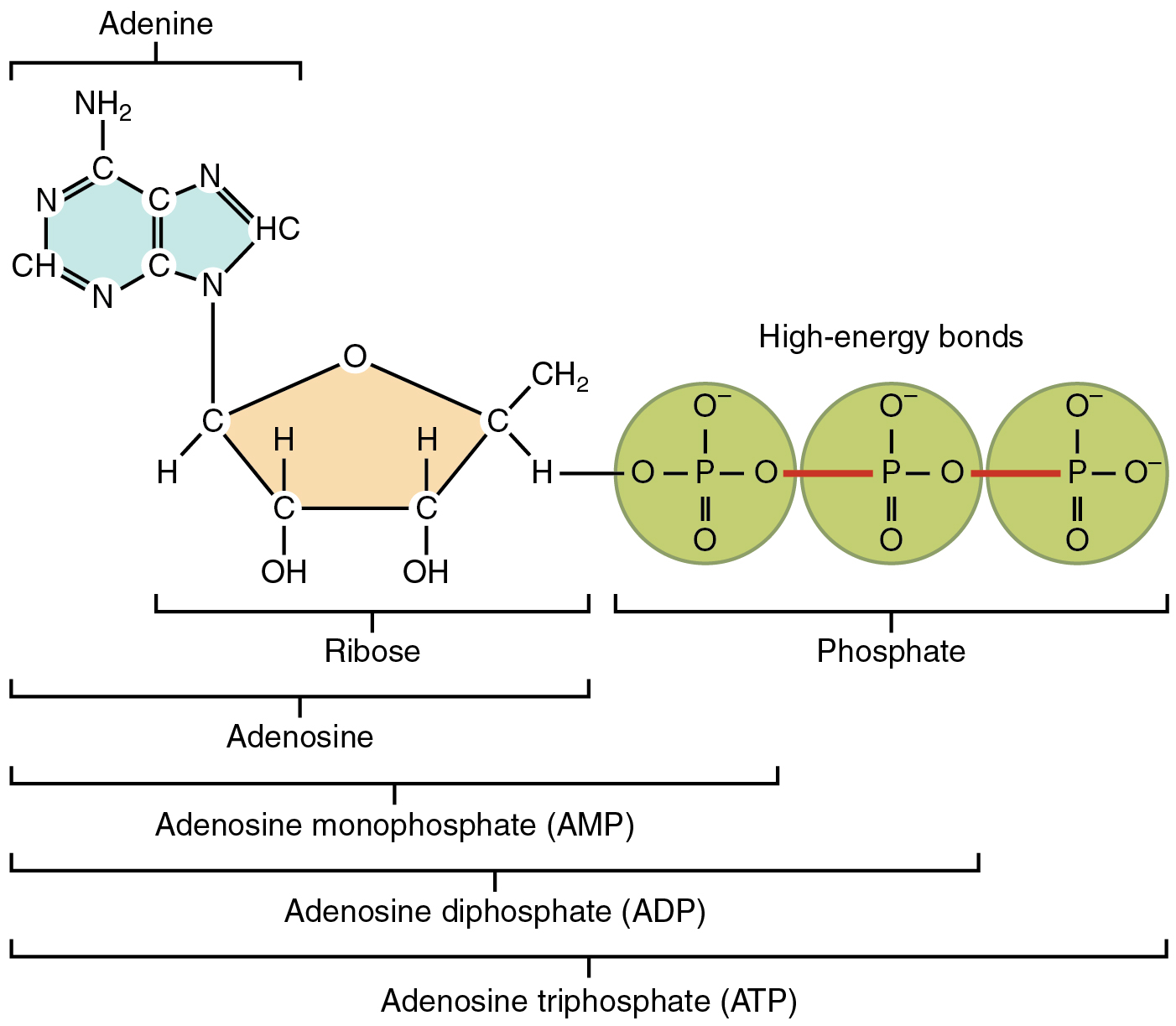

ATP Contains Chemical Energy In Phosphate Bonds

The blue, beige, and green shaded areas, taken together, comprise the entire ATP molecule. The chemical bonds between phosphate groups, indicated in red, are the high energy bonds that release free energy when subjected to hydrolysis. Note the close proximity of the negatively charged oxygen ions within the phosphate groups. Image courtesy of Wikimedia.

First, know that ATP is produced by four distinct metabolic processes:[10]

- Cellular Respiration,

- Beta-Oxidation,

- Ketosis, or

- Anaerobic Respiration.

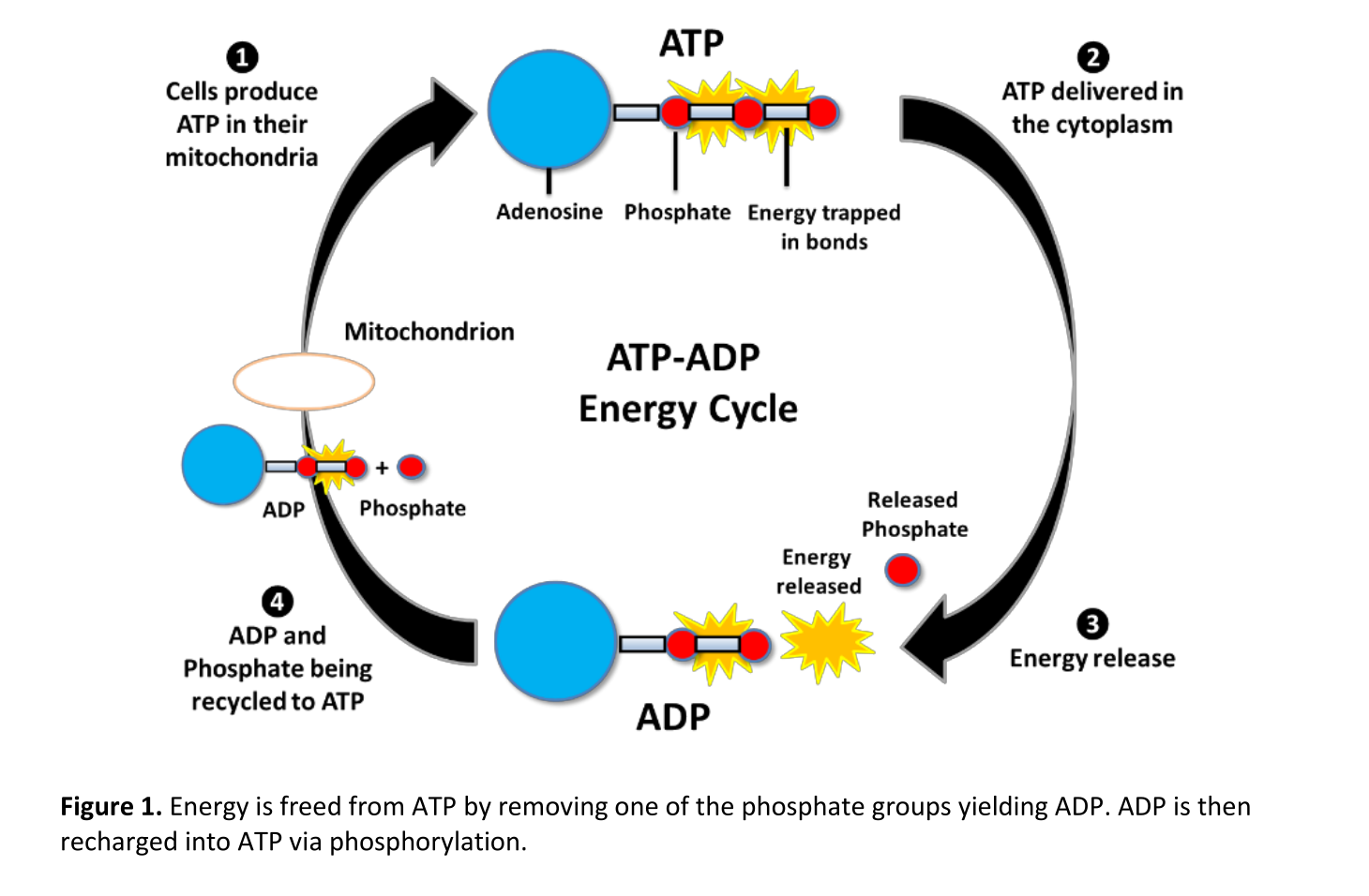

We won't go into detail on how each of these processes works, because they're each complicated enough for their own article. All you really have to know, for our purposes, is that each process uses some kind of electrical gradient to "pack" energy into the chemical bonds between the phosphate groups of the ATP molecule.[10]

We call these bonds high-energy bonds because, well, they contain a lot of energy.

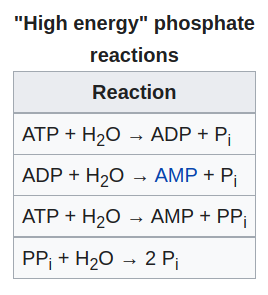

High Energy Bonds Release Energy When Hydrolyzed

Referring back to our diagram of the ATP molecule's chemical structure, we can see that the negatively charged oxygen ions are in close proximity to one another. This is the conceptual key to understanding why ATP functions so well as an energy carrier.

Free phosphate groups (Pi) are released when ATP is hydrolyzed, releasing free energy. These phosphate groups are then joined to other molecules in a process called phosphorylation. Table taken from Wikipedia

Because similar electrical charges repel one another, the phosphate groups "want" very badly to get away from one another. But they are prevented from doing so by the high energy bond.

Once that bond is hydrolyzed, the potential energy between the phosphate groups is released as the newly detached phosphate group gets repelled by the others.

In other words, the hydrolysis of the high energy bond very much wants to happen because the ATP molecule is so unstable. All it needs is a little push to come apart and release energy in the process.

This energy-releasing reaction can be harnessed by the cell to power energetically unfavorable reactions.[8]

In this way, the cell can hydrolyze as many high energy bonds as it needs to create the free energy required to perform useful functions.

For example, the phosphate group that's released from ATP after the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP can be used to catalyze a reaction between glucose and fructose, forming sucrose.[8]

In fact, this process works much like the hydrolysis of ATP itself: The phosphate group, when joined to glucose, creates an unstable intermediate called glucose-P, which is highly reactive and "wants" to bond with fructose.[8]

Sorry if all of this is confusing – that's about as simple as we can make it. If you want a little more detail, check out the (free!) lesson, ATP and reaction coupling, at Khan Academy.[8]

The Big Takeaway: First Law of Thermodynamics

It's easy to get bogged down in the chemistry details, which is why we tried our best to simplify it.

But the big picture concept you have to bear in mind about the workings of cellular machinery is this: Cellular function, like everything else, is subject to the first law of thermodynamics, which states that energy can be neither created nor destroyed.

This implies that if you consider a human cell as a closed thermodynamic system, every single energy expenditure within the cell must be balanced by an equal energy input.

The free energy released by hydrolyzing high energy phosphate bonds in the ATP molecule is what creates an energy input, allowing the cell where the hydrolysis is taking place to then expend energy on other useful tasks.

In other words: no free energy from ATP hydrolysis, no cellular work.

And without cellular work, there not cellular functioning. Lack of ATP can lead to cellular death.

Why Supplement with ATP?

So now that you understand some of the chemical theory behind what ATP is and how it works, let's discuss how ATP supplementation can play into improved performance.

ATP Is The Final Metabolic End Product

When you consume any kind of food, it goes through a long chain of metabolic processes to become usable cellular energy.

For example, let's say you eat something that contains a lot of starch, a polysaccharide carbohydrate (the type of carbs in foods like bread, potatoes, and pasta).

In order to transform into energy your cells can use, first that starch has to be pre-digested by enzymes, like amylase in your mouth. Then it goes to your stomach, which completes the process of hydrolyzing the starch into simple sugars. Once the glucose molecules are absorbed into your bloodstream, they have to be shuttled into your cells by insulin. Once inside the cell, the glucose is subjected to glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. Only after a final, second phase of glycolysis is the phosphorylated glucose turned into ATP.[11]

That's seven distinct metabolic steps required to turn starch into ATP, and this isn't even really a complete list. Certain things have been omitted or condensed for the sake of simplicity.

These steps take time, but during exercise, we want more ATP now:

ATP Is Consumed During Exercise

Unsurprisingly, ATP is consumed at an elevated rate during exercise, and stores of ATP in muscle tissue can decline significantly if exercise is sufficiently intense.[3,4]

That's because your muscle cells use ATP to power muscle contractions during workouts. The demand generated by exercise can be intense – as high as 1,000-times the metabolic demand for ATP when your body is at rest.[3]

This dramatic increase in energy consumption during exercise eventually leads to the physiological state of fatigue, which all of us, no doubt, are intimately familiar with.

It isn't so much that your body runs out of ATP – this doesn't happen except under very extreme, and frankly, catastrophic circumstances. In fact, your body's metabolic systems have several redundancies to ensure this doesn't happen. The state of fatigue itself is a mechanism your body uses to force you to stop exercising before ATP runs out.[3]

What generally happens is that your body consumes so much energy substrate – the carbohydrates and fatty acids that your body uses to produce ATP (especially glycogen, a form of stored glucose that your body can rapidly convert to usable glucose) – that these metabolic failsafes get activated, and you eventually get so tired that you cannot exercise anymore.

Your body makes you stop, in order to prevent you from depleting your cellular energy levels to a dangerous extent.

Once you've finished your workout, your ability to recover is highly dependent on glycogen replenishment.[11] The food you eat following a workout gets converted into glycogen, thus refilling your body's stores, which enables muscle protein synthesis, among other things.[11] Without glycogen, you won't get maximum gains.

But remember, some of the food you eat also has to be burned on fueling your body's normal metabolic processes.

The research: ATP Disodium Can Improve Exercise Performance and Recovery

What if you took supplemental ATP alongside the food you eat to recover? Then your cells could use the ATP to perform normal functions, sparing some of the food to be used for glycogen synthesis instead. Or even better, consider taking supplemental ATP during or before a workout, allowing your muscles to burn the exogenous ATP for energy, leaving your body more "breathing room" for its own ATP stores.

We would expect to see improvements in performance and recovery from ATP supplementation.

Let's see what the research says about that.[12]

-

A Single dose of ATP disodium improved lower body resistance training

First we'll look at a study from 2019, published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.[13]

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, with a twist. Instead of having two separate populations, the subjects served as their own controls by completing two different workouts: for one workout, each subject got ATP disodium in the form of Peak ATP, and a placebo for the other workout.[13]

In each workout, the subjects were required to train to failure – which is the point where energy demands of the exercise exceed the body's energy supply. Performance was measured in terms of total weight lifted, which is calculated by multiplying the weight on the bar by the number of reps. This gives you a great idea of the total work performed during the workout.

Unsurprisingly, the subjects did better on ATP than they did on the placebo. What's shocking is the size of the effect.

On the placebo, the subjects lifted an average of 3,995.7 kilograms per workout.

After taking ATP, they lifted an average of 4,967.4 kilograms per workout![13] That's a 25% increase in total work performed.

Granted, the sample size used in this study was relatively small, but nonetheless, we rarely see effect sizes this big in studies on ergogenic aids.

And remember – nobody knew which treatment the subjects had received for any given workout, so nobody could have thrown the results. The difference in performance was spontaneous.[13]

-

A nitric oxide booster

We all know that exercise is one of the best ways to take care of your cardiovascular system. Intense physical efforts cause the heart to work harder, while at the same time arteries dilate to permit more blood flow. Over time, repeated bouts of exercise can strengthen the heart and help increase the plasticity of the arteries, which improves your cardiovascular function when you're at rest.

So what does this have to do with ATP? As it turns out, ATP is a major factor in cardiovascular function:

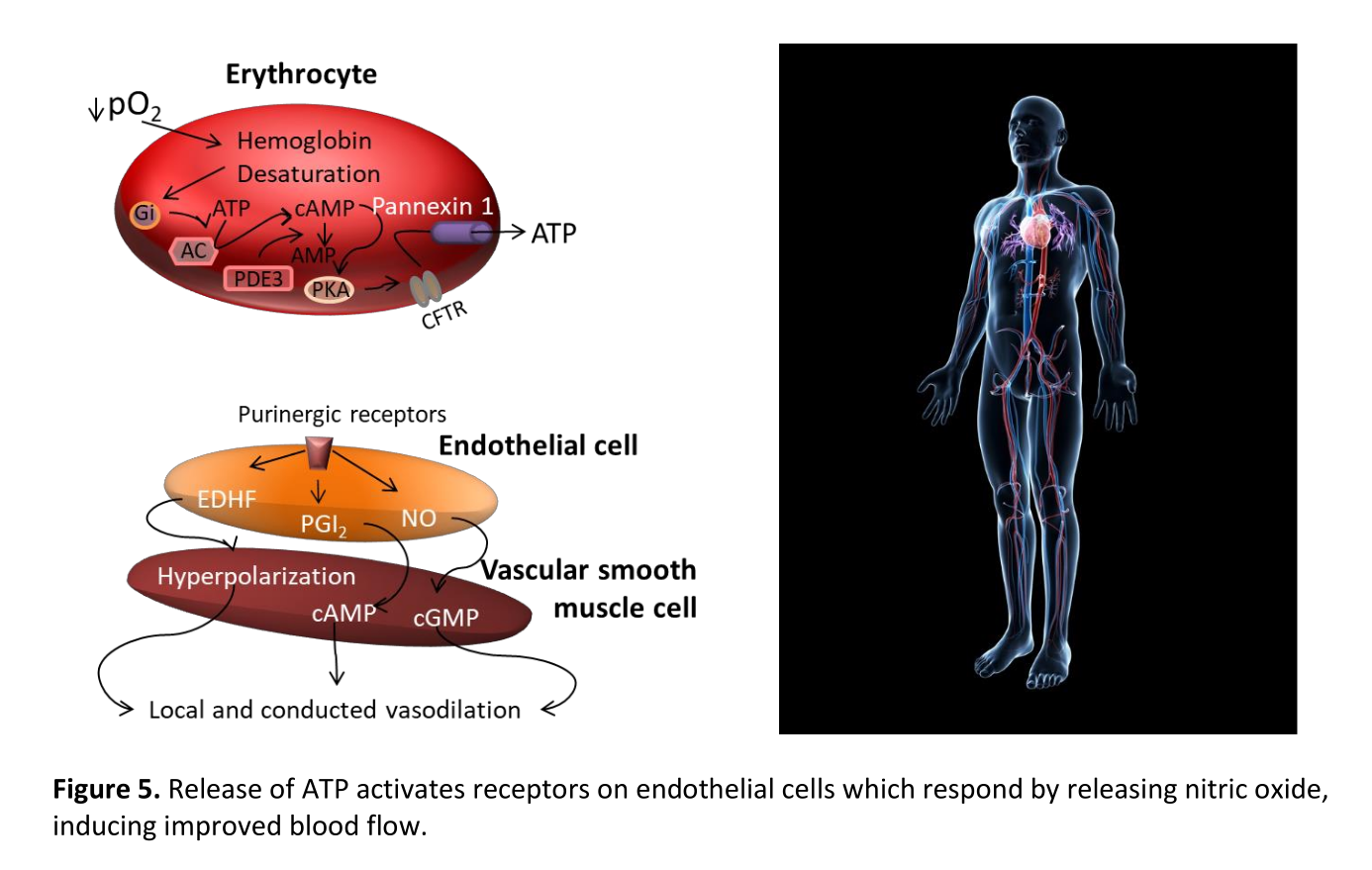

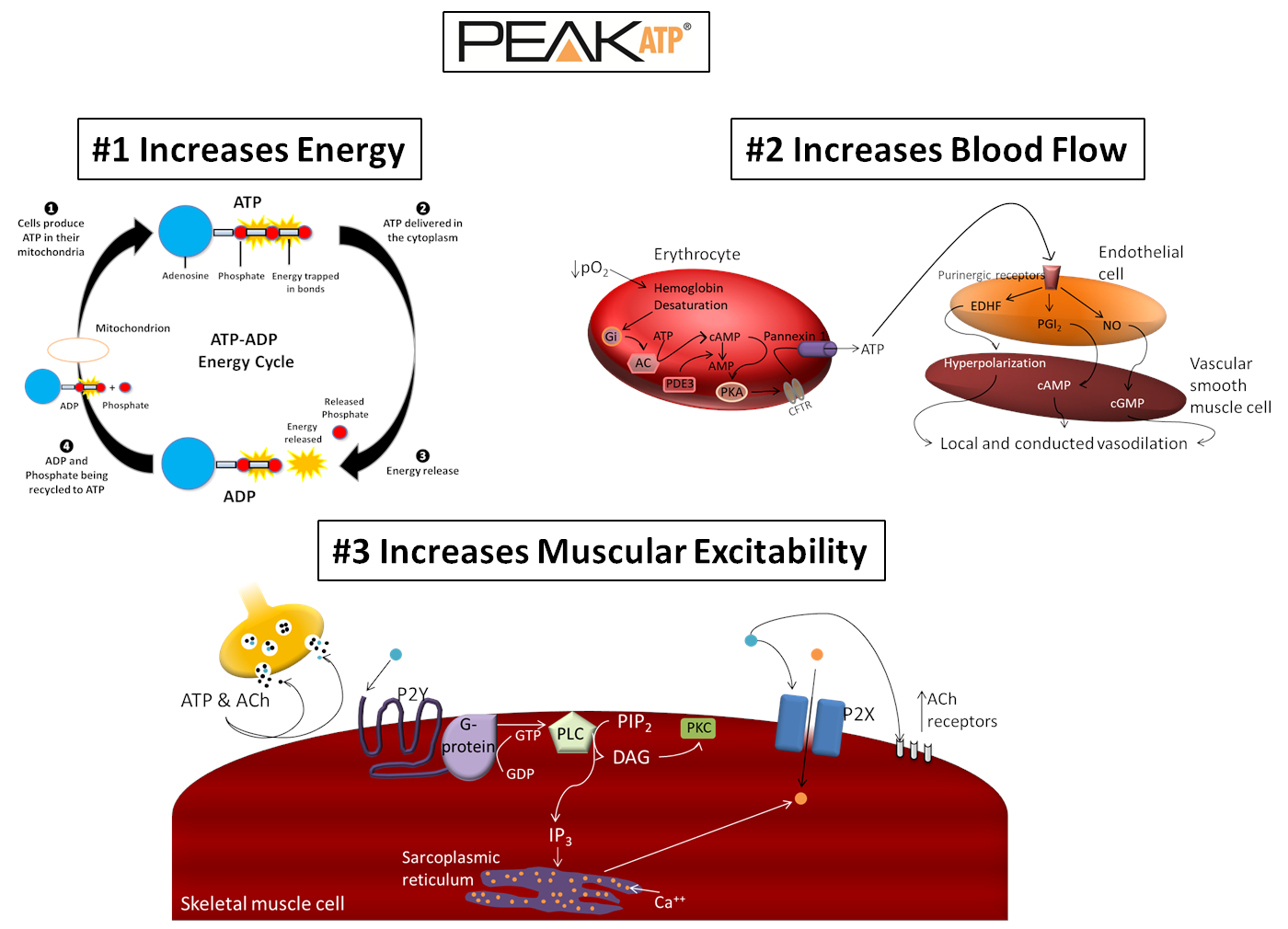

Once released, ATP binds to purinergic (P2X and P2Y) receptors on endothelial cells. Binding results in the endothelial cells releasing nitric oxide via endothelial nitric oxide synthase, prostacyclin, and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, all 3 of which affect the smooth muscle of the vasculature via cyclic guanosine monophosphate, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, and hyperpolarization, respectively.[9]

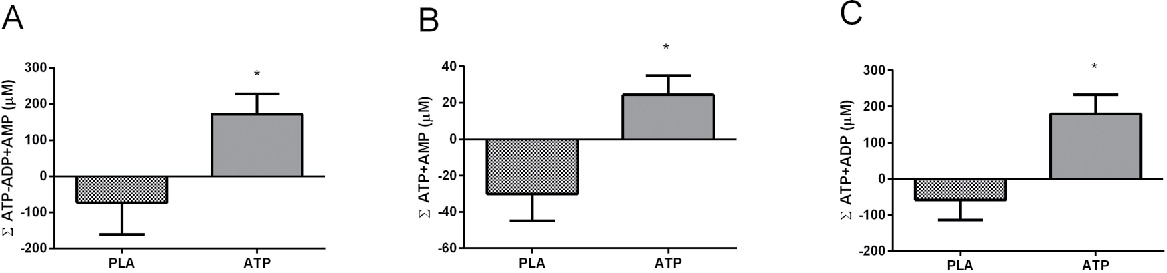

This was discussed in a study where oral disodium ATP administration was shown to increase post-exercise ATP levels, muscle excitability, and athletic performance after repeated sprint bouts:[9]

Again, we see the importance of cellular energy. Endothelial cells need energy to synthesize endothelial nitric oxide! Supplying them with that energy, in the form of ATP, makes them more likely to successfully do their job.

-

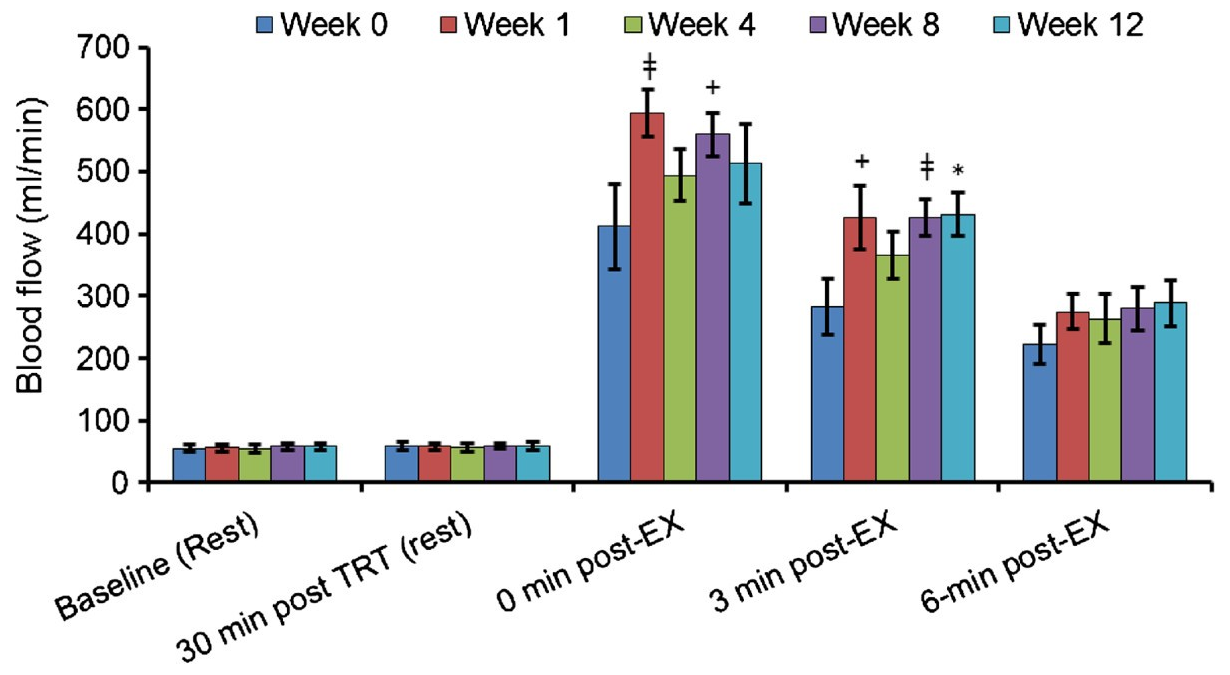

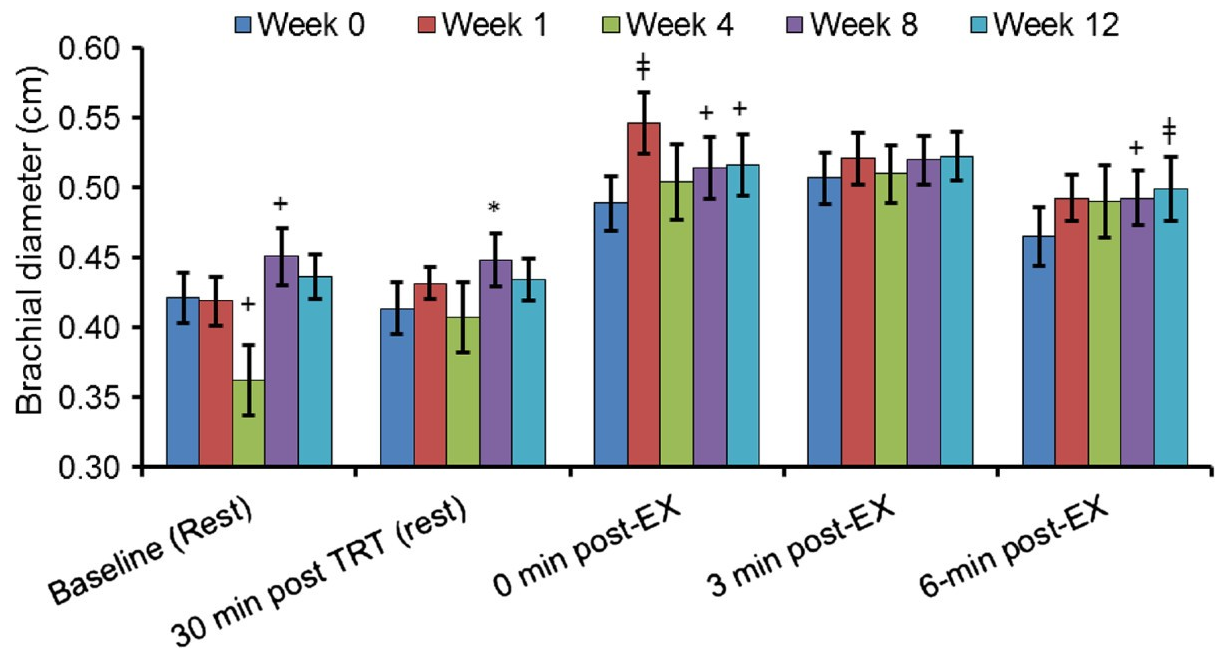

ATP disodium increases cardiovascular response to exercise

Next, a 2014 study published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition set out to establish whether supplemental ATP could enhance the cardiovascular response to exercise.[14]

After all, exercise itself takes energy – energy that gets diverted to muscle cells is energy that your endothelial cells can't use on nitric oxide synthesis. So the question is: If you gave your body extra ATP, would that cause an upregulation in endothelial function?

Improved blood flow!

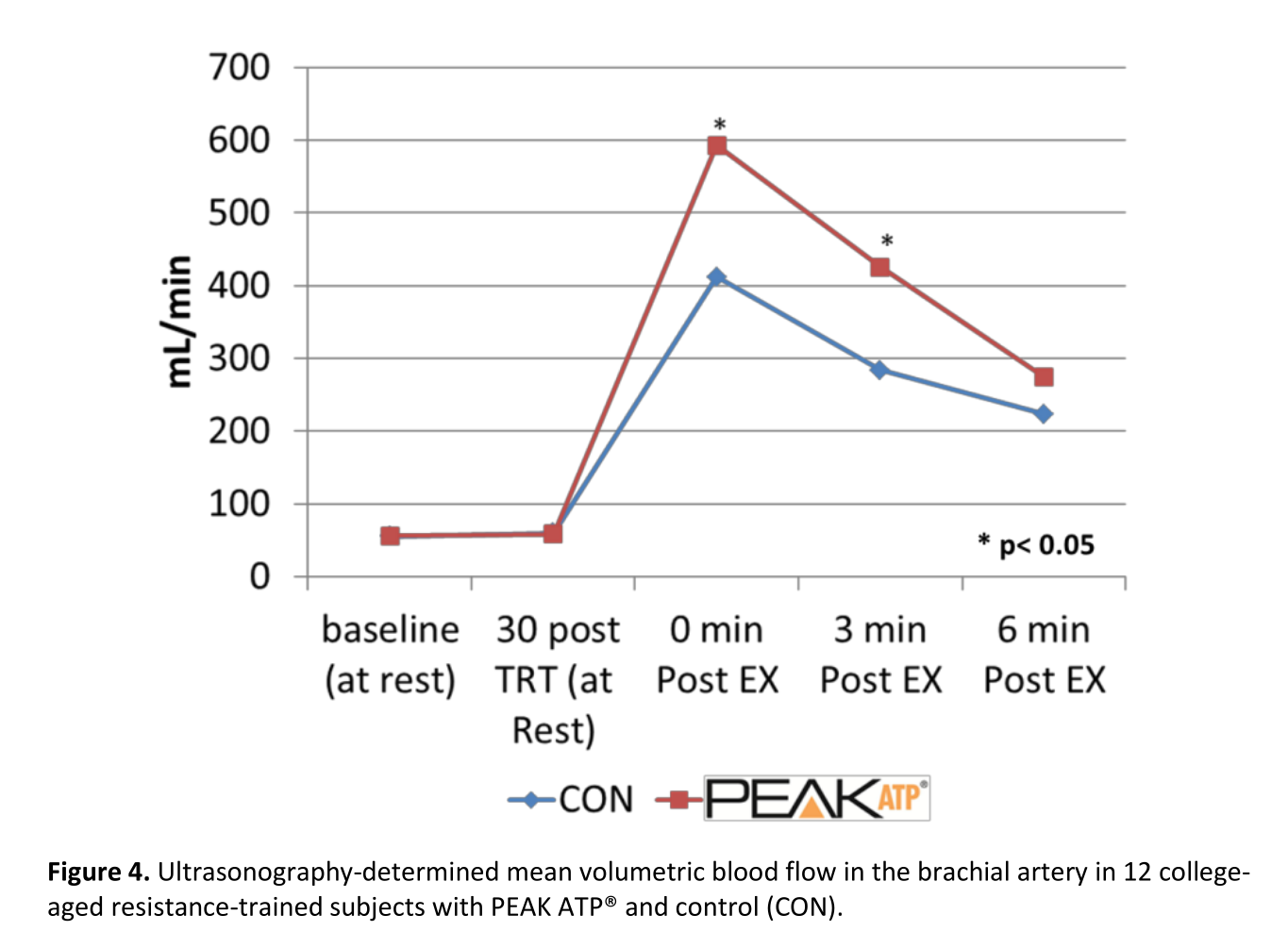

In this study, a 400 milligram of Peak ATP taken 30 minutes prior to exercise for one week led to improved blood flow after elbow flexor exercises in men compared to controls, as measured by ultrasound.[14] The blood flow improvements continued post-exercise as well:

Human data from Jäger et al.[14] After 12 weeks of ATP supplementation, human subjects showed significantly greater blood flow and brachial diameter following arm exercise.

It should be said that this study was not placebo controlled, although sophisticated statistical techniques were used to help overcome this limitation.

Additionally, the subjects selected for the study were already trained – each subject had been weightlifting for quite some time before the study began. This means that they should have been fully adapted to the exercise they were performing, as each volunteer was instructed to maintain their normal training regimen and volume.[14]

The results really speak for themselves: After 12 weeks of ATP supplementation, the subjects' brachial artery blood flow was nearly 50% higher than the baseline.[14]

Human data from Jäger et al.[14] After 12 weeks of ATP supplementation, human subjects showed significantly greater blood flow and brachial diameter following arm exercise.

Before that, improved blood flow response to exercise from Peak ATP had also been seen in 2013 in a study published in both animals and humans.[15] And recall the study above, where the researchers discuss the nitric oxide boosting mechanism after finding increased postexercise ATP levels.[9]

400 mg of PEAK ATP® supplementation significantly increased blood

flow and significantly enhanced brachial artery dilation following resistance exercise.[14]We further discuss the mechanism of action behind this below, because it's something that should be better understood in the supplement industry.

Again, the study above was not a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, and the researchers freely acknowledge those limitations.

However, it's an excellent indication that there is potential to use Peak ATP for cardiovascular reasons. The authors of the study propose to conduct a similar study with placebo controls in the future, and we agree that this research should be done if pursuing this category.

-

ATP disodium increases total body strength, vertical jump power and muscle thickness

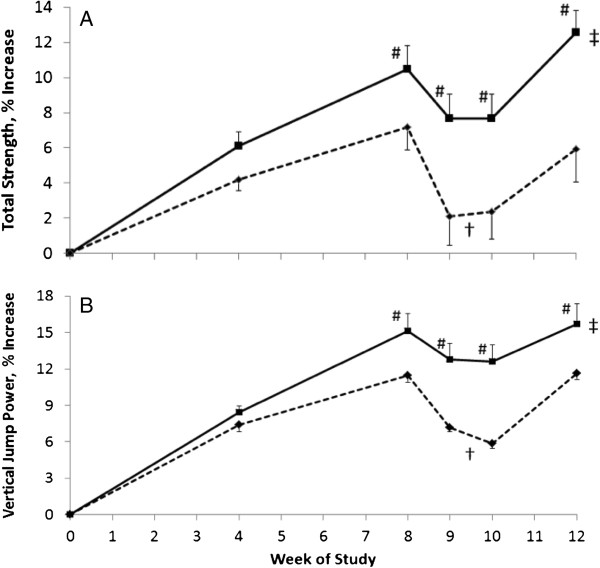

Next up is a 2013 study published in the London-based journal, Nutrition and Metabolism.

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study – remember, the gold standard of study design – researchers recruited resistance-trained males and gave them either the ATP disodium or the placebo. The participants in the ATP group got 400 milligrams of ATP disodium daily, over the course of 12 weeks.[16]

Additionally, this study was diet controlled, meaning the participants ate a diet prescribed by the researchers.[16]

The participants' 1 rep max on the "big three" lifts of powerlifting – barbell squat, deadlift, and bench press – were taken at baseline and throughout the study period. The same methodology was applied to the subjects' vertical jump power (measured in watts) and muscle thickness.[16]

The researchers found that although both groups gained strength on the 1-rep-max lifts throughout the study period, the ATP disodium group gained more strength. Specifically, the ATP group's strength increase on all three lifts combined was about 55 kilograms. The placebo group's increase was only 22 kilograms.[16]

When it came to vertical jump power, the ATP group again outperformed the placebo group: The ATP group increased their jump power by about 15%, whereas the placebo group only increased their jump power by about 11%.[16]

Finally, the ATP disodium group gained significantly more muscle than the placebo group. The ATP disodium group's muscle thickness, as measured by ultrasound, increased by about 5 millimeters. The placebo group got only half that increase![16]

Check out what the researchers had to say about ATP's ability to increase muscle thickness:

"In addition to ATP's capacity to buffer fatigue during repeated high volume sets and increase total training volume, the supplement may increase skeletal muscle blood flow, thereby enhancing muscle O2 recovery. This is critical as muscle deoxygenation is associated with decreased performance under repeated high intensity contractions. Specifically, extracellular ATP directly promotes the increased synthesis and release of nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGl2) within skeletal muscle and therefore directly affects tissue vasodilation and blood flow. This is supported by research suggesting increased vasodilation and blood flow in response to intra-arterial infusion and exogenous administration of ATP. It can be speculated that these changes in blood flow may lead to an increased substrate pool for skeletal muscle by virtue of increased glucose and O2 uptake."[16]

This proposed mechanism of action dovetails nicely with what we reviewed in the previous study, and highlights the importance of optimal cardiovascular function for all aspects of training and recovery.

-

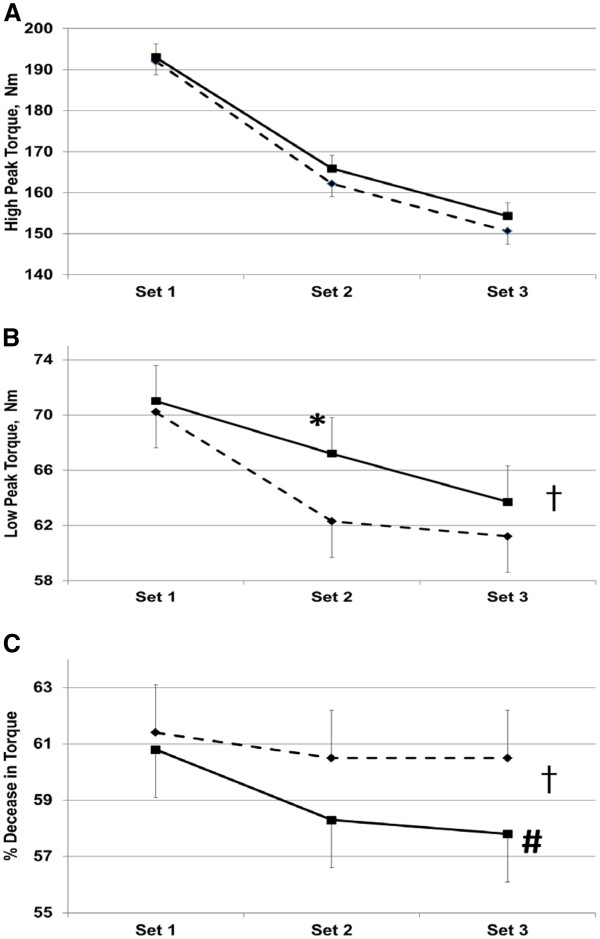

ATP disodium increases torque during resistance exercise

Subjects who received 400 milligrams of ATP disodium performed better on 3 sets of 50 leg extensions than those who received the placebo. Low peak torque is defined as the value of the lowest peak torque produced during the last 10 contractions of each of the 50 contraction fatigue test.[17]

Finally, let's talk about a study from 2012, published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition.[17]

This study had an elegant but effective design: Subjects were randomized to either ATP disodium or a placebo, which they took for 15 days and then performed 3 sets of 50 knee extensions on a machine that measured their ability to produce torque throughout the exercise.[17]

Throughout the leg extensions, those subjects who'd been supplementing with ATP disodium had significantly higher peak torque, and fatigued significantly less than the placebo group.[17]

-

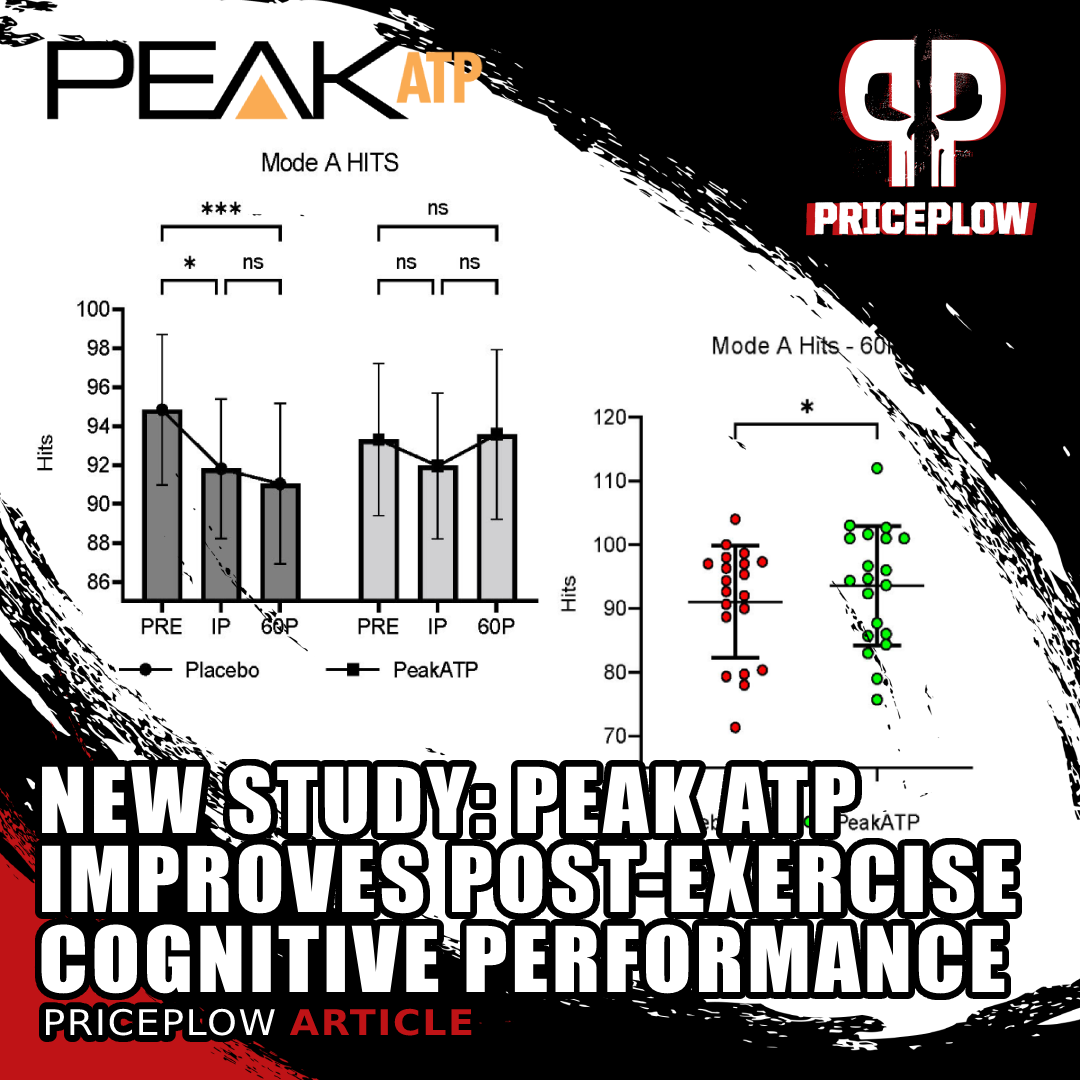

2023 Nootropic Study: Peak ATP Improves Post-Exercise Cognitive Performance

A new study published in Frontiers in Nutrition in 2023 demonstrated that Peak ATP helped prevent the temporary decline in cognitive function that normally occurs following intense exercise.[18] The study used a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover method and showed Peak ATP's efficacy after 14 days of use at 400 milligrams per day.

Of the measurements taken were reaction time and hand-eye coordination, as well as ocular reaction time.

Exercise can create a feeling of mental fatigue by eliciting deficits in attention and processing speed. A study published in 2023 showed that PEAK ATP® helps mitigate deficits in several cognitive tasks following exercise.[18]

You can read more about the study in our article titled "Nootropic Study: PEAK ATP Improves Cognitive Performance After Intense Exercise".

Conclusion from the overall body of research

Overall, a 2021 review concludes the following, also citing a few earlier studies not covered above:[12]

The available literature on ATP disodium when provided in a dose of at least 400 mg approximately 30 min before a workout or 20–30 min before breakfast on non-exercise days provides insight into its potential to reduce fatigue (Purpura et al., 2017,[9] Rathmacher et al., 2012[17]), increase strength and power (Wilson et al., 2013[16]), improve body composition (Hirsch et al., 2017[19], Wilson et al., 2013[16]), maintain muscle health during stress (Long and Zhang, 2014,[20] Wilson et al., 2013[16]), increase recovery and reduce pain (de Freitas et al., 2018[13], Khakh and Burnstock, 2009,[21] Wilson et al., 2013[16]). Additionally, other literature indicates a role for ATP in improving cardiovascular health (Hirsch et al., 2017,[19] Ju et al., 2016,[22] Rossignol et al., 2005[23]).[12]

The Triple Mechanism of Action

Much of the above research is unsurprising, given ATP's triple mechanism of action. As a universally-utilized molecule in the body, it actually has uses and influences that vary from tissue to tissue,[21] so there are several potential benefits from supplying more.

First, it's involved in anabolic signaling, and is responsible for triggering signaling cascades related to neuromuscular activity through phosphorylation of ERK1/2. This can result in increased lean body mass and muscle thickness, as shown in the studies above.

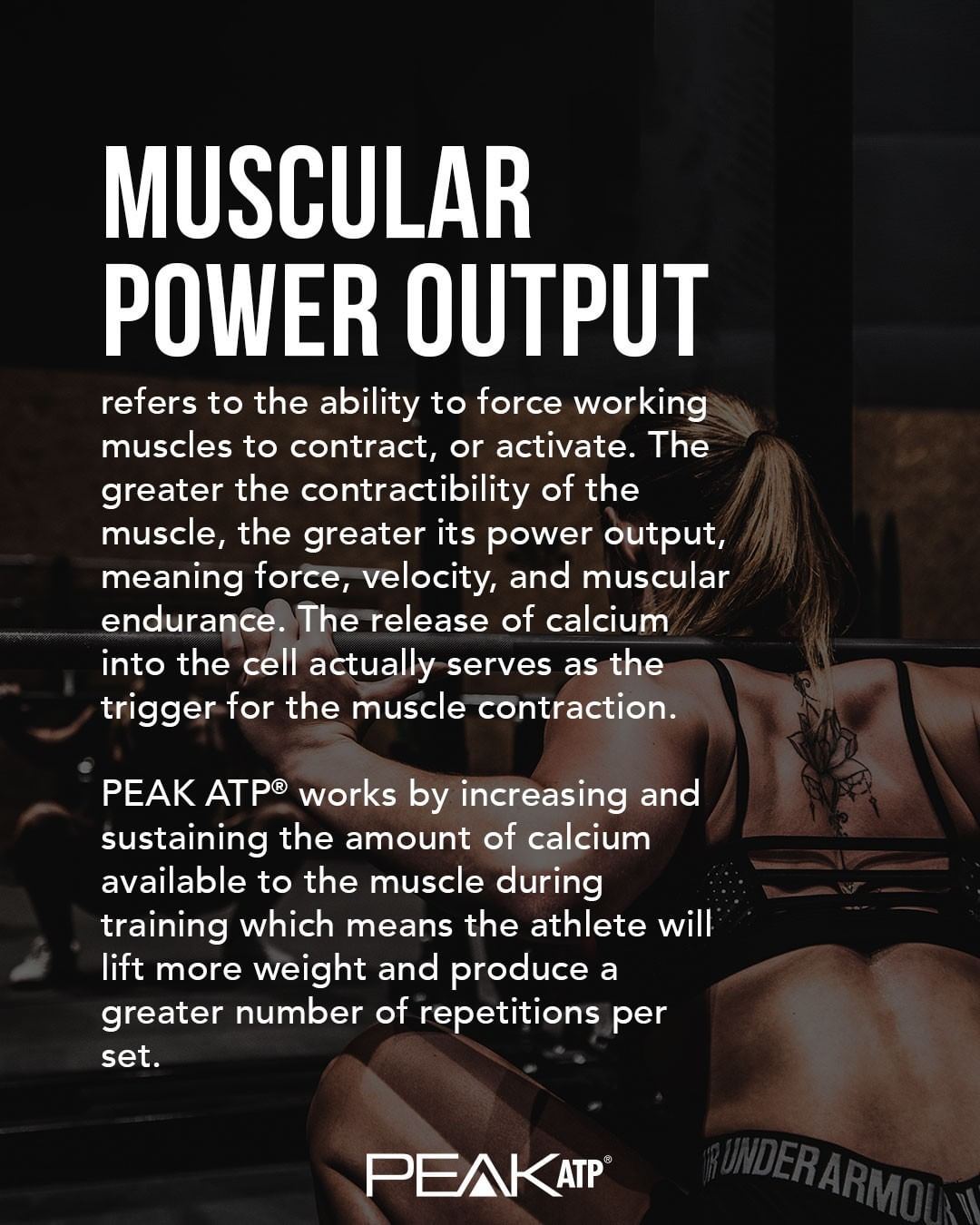

Moreover, ATP can increase muscular contractions, leading to significant gains in strength and power. But further, there's another mechanism that's not as frequently discussed:

Another mechanism of action: blood flow improvements!

It's not just that Peak ATP is providing more ATP for the body to acutely use - there's an interesting blood flow related mechanism that underlies its success. We already saw improvements to blood flow after just one week of use of Peak ATP.[14]

How was that accomplished? In the other study cited above that demonstrates how ATP disodium increases the cardiovascular response to exercise, the authors illuminate some very interesting biological information in their introduction:[16]

It has been reported that the half-life of infused ATP is less than one second,[24-26] ATP is rapidly taken up and stored by erythrocytes.[24] This rapid uptake by erythrocytes is central to its role in affecting blood flow and oxygen delivery to oxygen-depleted tissue.[27]

Specifically, there is a tight coupling between oxygen demand in skeletal muscle and increases in blood flow. Erythrocytes regulate this response by acting as "oxygen sensors".[28] When oxygen is low in a working muscle region, the red blood cell deforms, and releases ATP.[28,29] The result is vasodilation and greater blood flow to the working musculature, thereby enhancing nutrient and oxygen delivery.[28,29]

Long-term oral administration of ATP has been shown to increase both the uptake and synthesis of ATP in the erythrocytes of rodents.[30] Collectively, these findings suggest that oral ATP supplementation may elicit ergogenic outcomes on skeletal muscle without elevating plasma ATP concentrations.

-- Wilson, et al, 2013.[16]

What the researchers are postulating here is that ATP's mechanism may actually be acute blood flow mediation, and not merely the addition of more ATP to the system!

The researchers then discuss some of their results in their conclusion, and postulate the reasoning:[16]

Our results indicated greater increases in LBM and muscle thickness in response to oral ATP versus placebo. We can speculate on a number of possible reasons for the ergogenic effects of ATP on muscle mass we have observed. In addition to ATP's capacity to buffer fatigue during repeated high volume sets and increase total training volume, the supplement may increase skeletal muscle blood flow, thereby enhancing muscle O2 recovery.

This is critical as muscle deoxygenation is associated with decreased performance under repeated high intensity contractions.[31] Specifically, extracellular ATP directly promotes the increased synthesis and release of nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin (PGl2) within skeletal muscle and therefore directly affects tissue vasodilation and blood flow.[32] This is supported by research suggesting increased vasodilation and blood flow in response to intra-arterial infusion[33] and exogenous administration of ATP.

It can be speculated that these changes in blood flow may lead to an increased substrate pool for skeletal muscle by virtue of increased glucose and O2 uptake.[27]

-- Wilson, et al, 2013.[16]

Emphasis ours above. This teaches us that Peak ATP is actually a blood flow supplement more than just an "exogenous energy" supplement! Perhaps this will be an area of research for TSI Group to explore even further in the future, although we've already seen one study where Peak ATP led to improved blood flow.[14]

With this now in mind, we're surprised we don't see the ingredient in more stimulant-free pre-workout supplements that are meant to increase blood flow and "muscle pumps". These supplements often rely on improved nitric oxide levels to achieve their goals, and the ATP mechanism of action is right in line with their goals.

On that note, below are some key supplements utilizing Peak ATP:

Supplements with Peak ATP

Are you ready for your legacy? AP Regimen released their Legacy Series Pre-Workout and Pump Supplements, and the stimulant-based Pre-Workout has Peak ATP

Ready to try Peak ATP to test the incredible advantage of exogenous ATP disodium? Below are a few key supplements containing it. After that, you can see all of the articles we've written about it:

- Pre-Workout Supplements: Beyond Raw Concept X and Alpha Prime Supps Legacy Pre-Workout

- Stimulant-Free Pre Workout Supplement: NatureCity TrueNOx

- Creatine Supplements: MuscleTech Cell-Tech Elite

- Standalone Peak ATP: MuscleTech Muscle Builder

The dosage used: 400 milligrams

You'll consistently see that 400 milligrams is the clinically-verified dose, used for over a decade.

In Episode #078 of the PricePlow Podcast, Dr. Ralf Jaeger dove into ATP, explaining how supplementing Peak ATP improves workout performance.

To verify that this is the most cost-effective dose, researchers tested 100, 200, and 400 milligrams or a placebo in a randomized crossover study published in 2021.[34] They verified that compared to placebo, 400 milligrams of Peak ATP significantly increased the number of repetitions in the first set, the number of total repetitions, and total weight lifted. 200 milligrams increased the number of repetitions in the first set, and placebo had no improvements.[34]

This indicates that 200 milligrams helped a touch, but wasn't enough to power a significant increase throughout an entire workout, which is why formulators are sticking at 400 milligrams.

Listen to Dr. Ralf Jaeger explain ATP on the PricePlow Podcast!

In Episode #078 of the PricePlow Podcast, Dr. Ralf Jaeger dove into ATP, explaining how supplementing Peak ATP improves workout performance.

You can see a video of the discussion below:

Previous PricePlow Blog Articles Mentioning Peak ATP

Conclusion: Peak ATP is more than an “ATP Supplement”

We began our research looking at ATP as an energy substrate, but ended up in a complete separate area - blood flow improvement. This is the nature of science, and is something we've come to expect -- -- twists and turns are the norm. All the more true when considering a biological chemical that's so paramount to human health.

TSI Group has an incredible ingredient on its hands, and now that we better understand how it works, we don't think we're seeing the full and best utilization of it just yet. And that excites us, because there's so much more to be explored and researched.

Mark our words: we firmly believe that bioenergetics and cellular health are the future of health and supplementation. Healthy mitochondria lead to healthy bodies, and healthy bodies need healthy blood flow. With improved ATP status and exercise, we may just be able to get both of those.

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

MuscleTech Platinum Muscle Builder – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Note: This article was originally published on September 11, 2019 and updated October 14, 2022 and August 23, 2023 with the new research supporting reduced post-exercise cognitive decline.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)