We've always "known", but now we know. In lieu of the "Standard American Diet", eating your fruits and vegetables makes you live longer.

Or, to put it in a way that will hit closer to home, not eating vegetables in this food environment generally makes one die sooner.

This meta-analysis makes it about as official as we can get: if you eat 4-5 servings of fruits and vegetables, then all other things equal, you will live longer.

Nearly every health enthusiast, doctor, and loving grandmother has always recommended eating plenty of fruits and veggies, but didn't have much slam-dunk data showing that they provide serious, life-altering effects compared to the standard Western diet.

That is no longer the case.

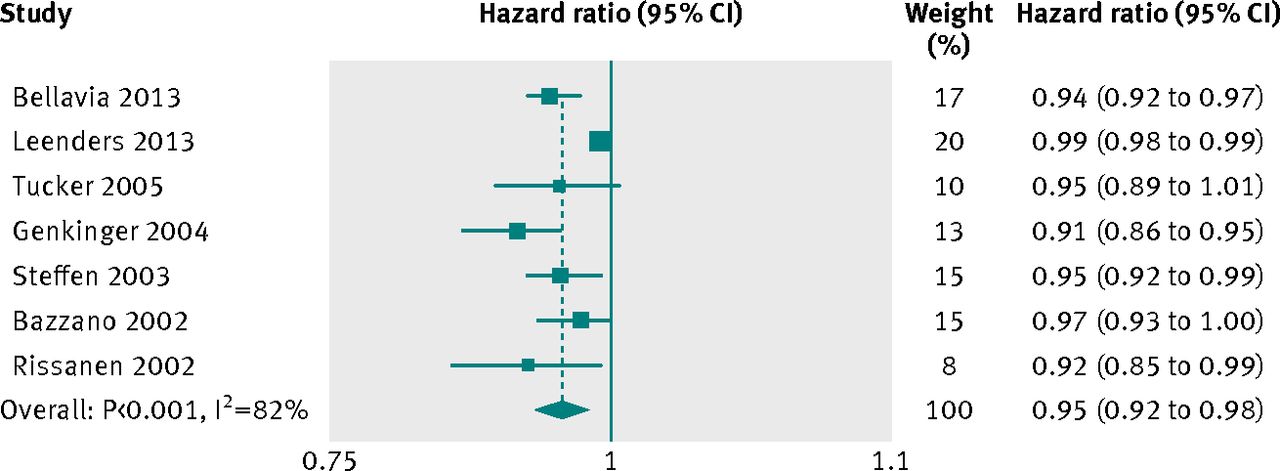

In 2014, a team of American and Chinese researchers came together to conduct a monstrous meta-analysis of diet and mortality data, and came away with one major conclusion: a diet high in fruits and vegetables leads to a longer life - and the data is basically universal no matter the other factors.[1]

Unfortunately, this paper didn't get as much press as it deserved, so we'd like to re-spark the conversation.

TL;DR

If you don't want to read the details, the key takeaway:

On average, a combined total of five servings of fruits and vegetables per day will yield significant benefits on your lifespan by reducing the risk of death by heart disease by 26%.

Do this each and every day, and all other things considered equal, you'll live a longer, healthier life than you otherwise would have.

The major question/caveat is, "If we went back to nutrient-rich eating organ meat and ditched the processed foods and seed oils, would this be necessary?!"

This monstrous meta-analysis confirms it about as much as we can confirm diet research: Eating 4-5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day significantly reduces your chance of death from cardiovascular disease

Now let's back that statement up with the data and the postulated reasoning why it works. After that, we'll provide some basic advice combining everything we currently know about diet, health, and body composition at this point.

The Fruit and Vegetable Mortality Research

The research is publicly available online:

The data behind the research: how good is it?

First, it's important to discuss whether or not this is clean data:

Data quality

A few major points show that this was indeed a very well-performed analysis:

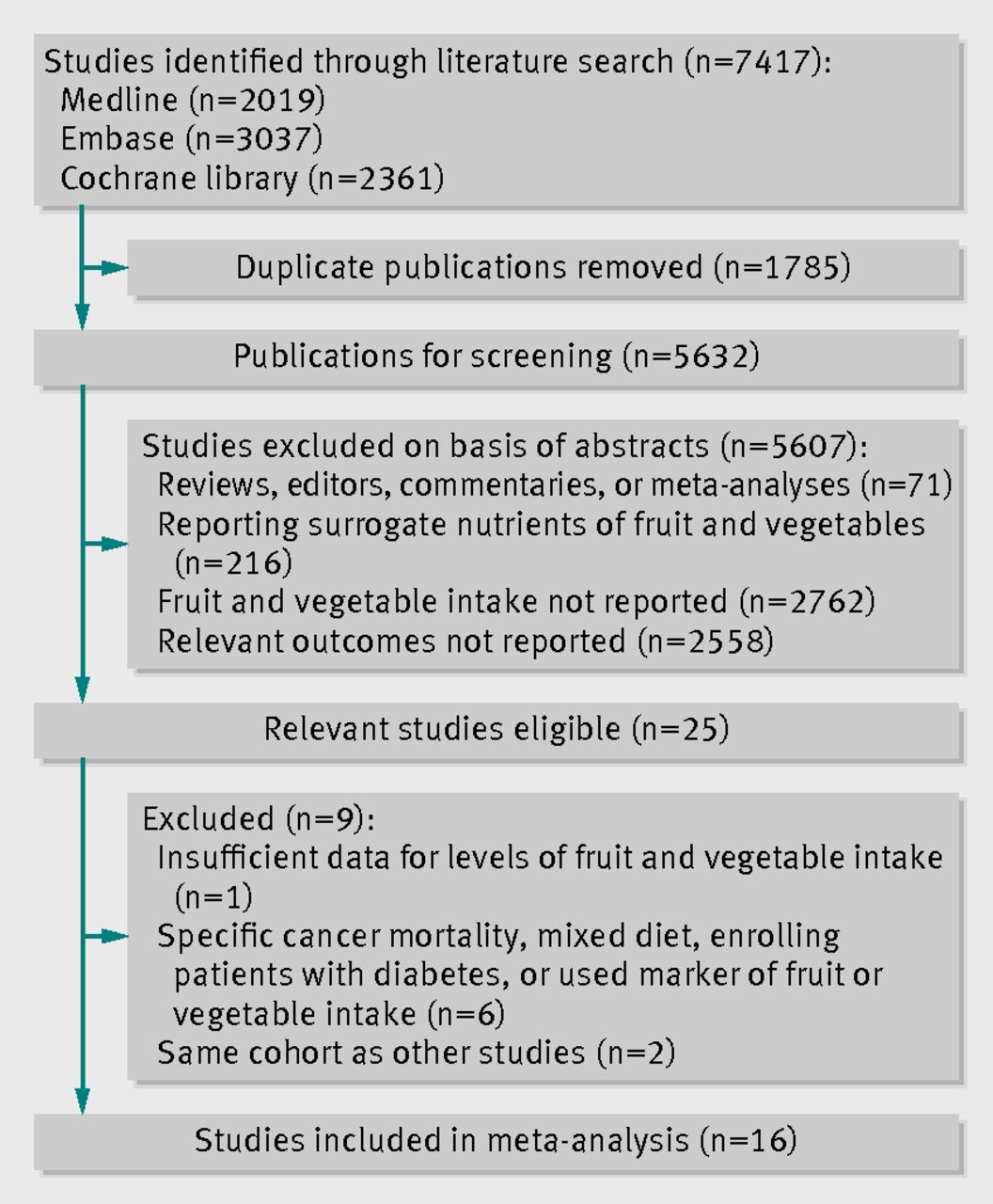

- The meta-analysis uses only primary sources of data - it doesn't include previously-performed meta analyses.

- It excludes all animal studies, and focuses only on humans.

No bad data in this study. Of 7,417 studies, only 16 were good enough to be used - but they still yielded over 833,000 participants.[1]

The data used studies ranging from 1950 through 2013, which were from several major medical publications.

- After finding potential studies to use, the researchers then isolated studies that dealt with various forms of mortality and were also paired with fruit and vegetable intake.

- They then screened each study with a fine-tooth comb and disqualified any study that did not meet all of their criteria, which removed questionable or poorly-collected data.

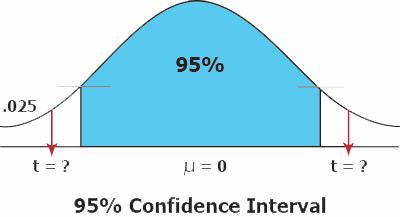

- They then ran a massive amount of statistical analysis. This included standardizing all data around their 95% confidence interval (i.e. not taking the previous researchers' conclusions at face value).

-

When temporarily re-analyzing the data, after removing the largest study (which was most heavily weighted due to its larger number of participants), the results did not appreciably change.

This means that even the biggest study did not have a disproportionate effect on this meta analysis' final conclusions.

The researchers were left with the following data:

- Sixteen studies were used

- The studies ranged from 4.6 to 26 years long

- There were 833,234 participants. There were a total of 56,423 deaths recorded. 11,512 were from cardiovascular disease, and 16,817 were due to cancer.

Is that enough data points?

You might be wondering if this is enough data to make blanket statements like this study is, given our massive populations. The quick answer is yes, but with one caveat: it depends on where you're from.

First, let's assess quantity. To make some estimates, in 1950, the world had a population of 2.56 billion[2]. In 2013, the population was 7.136 billion.

"Were this procedure to be repeated on multiple samples, the calculated confidence interval (which would differ for each sample) would encompass the true population parameter 95% of the time." Quote courtesy Wikimedia Commons

So, throughout the course of these research studies, let's be conservative and state that the average global population was 5.5 billion. This gives us data from 0.0151% of the population, which seems sparse, but it's actually far beyond what's required for us to get quality statistical data, and the data is shown for a 95% confidence interval.

If you don't understand confidence intervals in statistics, you might find StatTrek's explanation useful.[3] It's complicated and requires some prerequisite statistical knowledge, but the point is, the data is strong.

The bigger issue is demographic

While the quantity of data points (the 'N') is enough to provide strong confidence, the bigger issue is where they're from. The studies weren't simple random samples (SRS) from the global population because they were centralized to certain countries:

- Six were performed in the United States

- Six were in Europe:

-

One covered 10 countries

- One was all across the United Kingdom

- One in Wales

- Two in Sweden

- One Finland

-

- Four were in Asia:

- Three in Japan

- One in China

This is good news for most of our readers, who are primarily American and European. But if you are from other parts of the world - especially Africa and South America - then take the information with a grain of salt: it doesn't technically apply to you.

It doesn't take a leap of faith to project the data onto other cultures, including Canadians, but once again, the data is truly only valid for the geographies listed above (sorry Canucks!)

With that now known and accepted, we can get to the meat of the research:

The key findings

The primary amount of mortality research is about two things: cancer and cardiovascular disease. This makes sense, since they are the two main causes of death worldwide.[4]

It is the latter of those two - cardiovascular disease - where fruits and vegetables have the highest impact:

For each additional serving of fruit or vegetables, the risk of death by cardiovascular disease drops by 5%.

The benefits begin to cap out at a threshold of five total servings per day, where the risk of death is reduced by 26%. After that, mortality risk does not lower any further.

Interestingly, fruits "outperformed" vegetables: the fruit-based research studies showed that each additional serving of fruit decreased the likelihood of death by 6%, vs the 5% for vegetables!

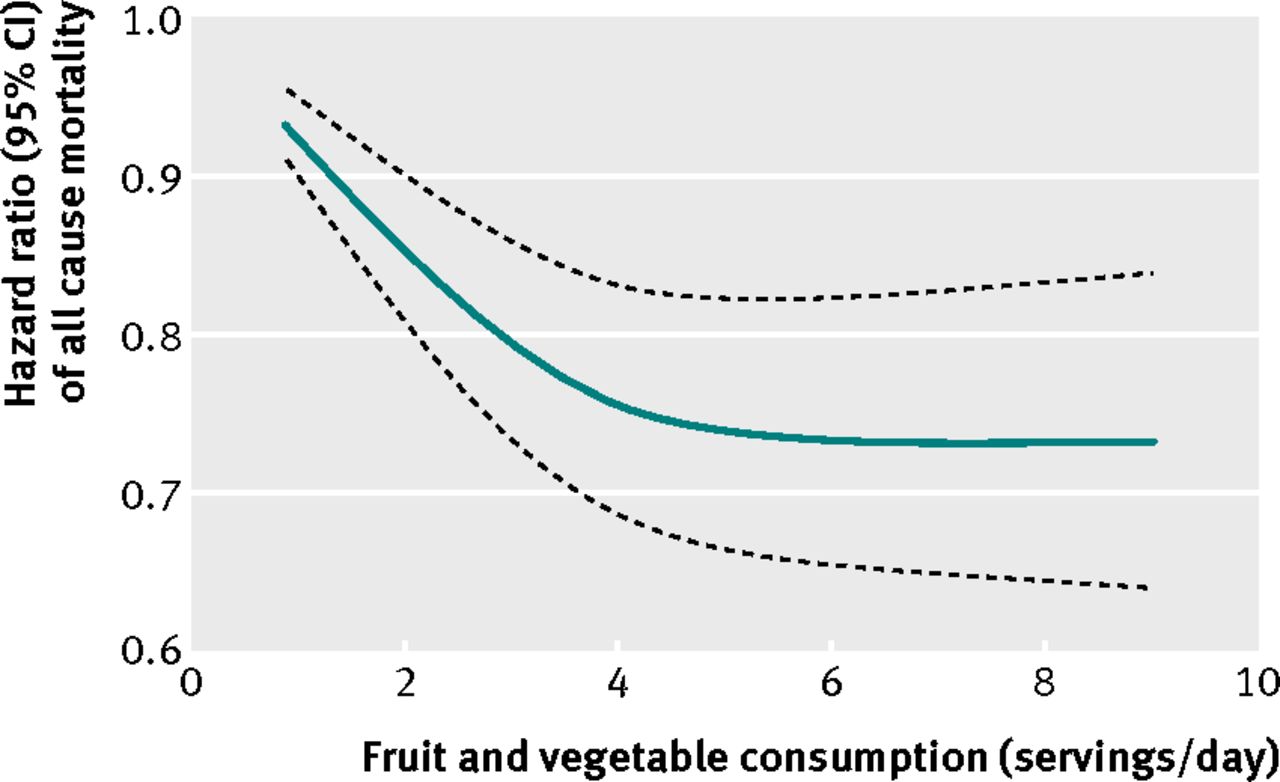

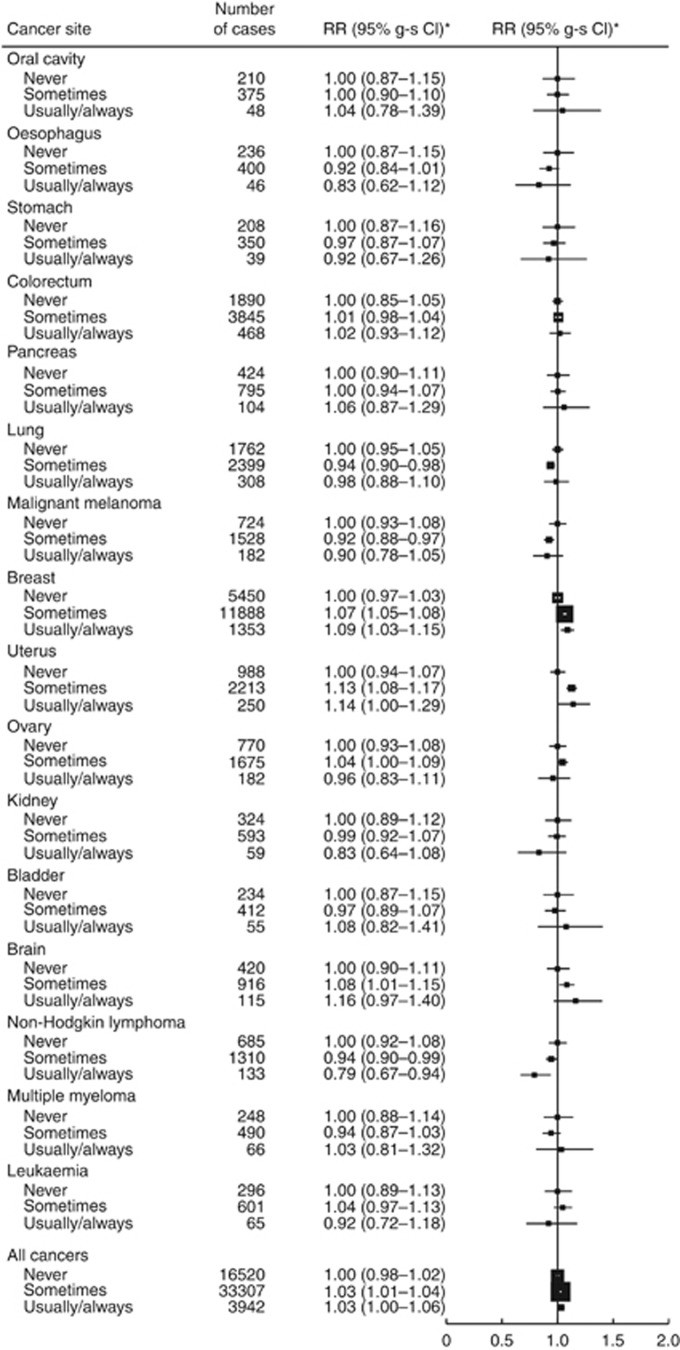

Results of the pooled analysis for all the included studies. The relation between fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of all cause mortality in this dataset was evaluated from seven of the studies, comprising 553,698 participants and 42,219 deaths

Note that we emphasize the reduction of cardiovascular disease here, since the data shows that cancer rates are largely (and unfortunately) unaffected in fruit and vegetable eaters. This is covered in greater detail further down.

The data is based on hazard ratios, so it's important to understand what that means first:

Understanding hazard ratios

The study states that "the estimated hazard ratios of all cause mortality were 0.74 for five servings per day".

What does this mean? Does it mean that there's a 74% chance I'm going to die tomorrow if I don't eat my veggies? No!

To best understand these hazard ratios, we enlist Dr. Terry Shaneyfelt of the UAB School of Medicine, who posted this to YouTube:

A hypothetical example

The best way of explaining this is to throw it into a hypothetical situation. Let's say that somewhere out there is a group of "Super Best Friends" who have a running tally on your health.

They determine that at any individual time, you have a certain "default" chance of dying from a cardiovascular event. Let's just say that when you're born, it's one in 2.5 billion (2.5 billion seconds equates to about 79 years, an average lifespan these days). As morbid as it sounds, on average, in one of those 2.5 billion seconds... your life is going to terminate.

Now, if you have been eating five servings of fruits / vegetables each day, this data basically states that your chance of cardiovascular death drops by 26%.

Vegetables and fruits save lives! A couple of these and a piece of fruit or two for the day and you're going to live longer. The key is in bulk cooking!

This takes your average hypothetical chances from one in 2.5 billion to one in 3.15 billion -- now 99.8 years on our average fictional scale - just under the century mark!

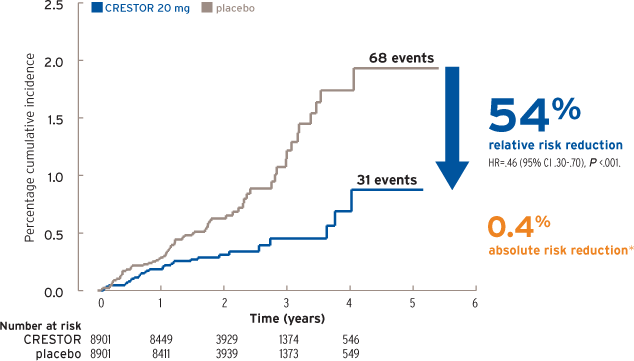

Don't look too deeply into the number of years -- they're made up and don't distinguish the difference between relative risk (which is taken at the end of a study) and hazard ratio (taken throughout the study).

The point is, all other things considered equal, you can seriously lengthen your lifespan and quality of life by eating your fruits and vegetables. In each waking second, your chances of not dying literally go down, and that time adds up.

Of course, these factors don't factor in other issues, such as getting hit by a bus.[5]

Where the data fails us

One issue that is difficult to determine with the data is the long-term time factor.

How long were these longer-living people eating their fruits and vegetables? All their lives? Did they start at the beginning of the study?

We simply don't know -- but we're willing to bet that most fruit and vegetable eaters were raised doing so. Eating patterns are strongly influenced by parents and caregivers,[6] so the majority of the adult fruit eaters studied were very likely always fruit-eaters. But that's not always the case.

This data is taken from a completely different study, but it shows a good example of the difference between relative risk reduction (which is at the end of the study) and absolute risk reduction. Our study deals mostly with hazard ratios, which are taken throughout the study. It's tough to determine a perfect relative risk reduction for a diet study such as this since we don't know when users began eating fruits or vegetables.

Yet, because of that data gap, we don't know how long it'll take for you to see benefits. If you're 50 years old and haven't eaten a vegetable for over forty years, we can't confidently say that you're ever going to get that 26% cardiovascular event risk reduction. But it clearly can't hurt to start.

And if you're young and relatively healthy, when will the full effects kick in if you start today? That we also don't know (although anecdotally, it usually takes a few weeks to start "feeling" better from high-vegetable diets).

Just realize that this isn't a diet gimmick, and this isn't gimmicky research.

It's simply meant to show that you that there are extremely strong correlations to fruit and vegetable consumption and lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

It plays into the entire lifestyle, and for best benefits, you need to commit for life - not just do a temporary cleanse or other such nonsense.

"But diet studies are flawed - users lie!"

At this point, you might ask, "Why should I believe this data? Everyone lies!"

And normally, we'd agree with you - too many diet studies are garbage because they're nearly impossible to control, and participants do in fact lie when self-reporting their eating.

The meta-analysis discusses this, and other problems, such as the fact that healthy eaters are also typically more active.[1]

However, in this case, that fact actually works in favor of the fruit-and-vegetable eaters.

Whereas unhealthy people may lie in diet studies about eating more fruits and vegetables than they really do, fruit and vegetable eaters almost never lie about it. This makes the data even stronger, because it's strong even with potential liars folded in.

Consider this: while there's a chance that an unhealthy person might state that they eat more vegetables than they really do, this is very little chance that a veggie-eater will state that they do not. After all, healthy eaters are quite proud of their lifestyles. Almost nobody "lies downward".

So, even with a number of "unhealthy eaters" who potentially lied about their eating habits, researchers were still able to find a great deal of correlation - despite what could possibly be tainted with a few extra people claiming to have eaten more fruit than they really did!

Point is, depending on how much users lied in their self-reporting, the real-life data could actually be better than is displayed here. But almost certainly not worse.

This is compared to diets that have otherwise been trash...

The most nutrient-dense foods are not vegetables -- they're organ meats! So what if we were to bring them back to the American diet and replace junk food with them instead? We have no data on this, but 'nose-to-tail' eaters are adamant over their effects. Image courtesy The Provision House

The next concern is that a fruit- and vegetable-enriched diet may function better than the "Standard American Diet" full of processed foods, refined grains, and toxic seed oils, but nearly every diet works better when you replace those!

This is extremely common for vegan dieters, for instance. They feel great compared to the soybean oil laden Standard American Diet, but does that mean it's optimal?

A diet full of meat eaten "nose to tail", including organ meats, contains just as many nutrients as one with fruits and vegetables. It's possible that the latter are not necessary as long as you're eating the former. Many nose-to-tail eaters argue this, but there is no data to substantiate it either way.

Point here being that replacing processed junk with fresh fruits and vegetables is beneficial, but may still not be optimal compared to replacing that junk food with grass-finished organ meat.

What is a "serving" of a fruit or vegetable?

Some studies used "servings" of fruits/vegetables, while others went by weight. The data was normalized to the following two definitions:

- A serving of vegetables = 77g

- A serving of fruit = 80g

To put that into perspective, here are a few fruit conversions:

- One medium-sized apple (3" diameter) = 182g[7], or roughly two servings once removing the core

- An extra-small banana (less than 6" long) = 81g[8]

- A small orange (2 ⅜" diameter) = 96g[9]

- Half of a cup of blueberries = 74g[10]

And for vegetables:

It really isn't hard to hit ~75-80g of food. A single apple will usually cover two servings! But salads rock for the variety...

Two and a half cups of spinach is roughly 75g[11]*

- One cup of chopped broccoli is 91g[12]

- Half of a large yellow bell pepper will yield 93g[13]

The point here?

This isn't hard to attain - the fruits are small portions! You basically need to eat an apple, a small piece of citrus or some berries, and make a medium-sized salad with a supporting veggie like carrot or broccoli and you're set!

There's literally NO excuse that you can't do this. We offer suggestions below, but we're not yet done discussing the study yet.

Not all cultures have the same fruits and vegetables

Note that this article was written by an American, so the fruits mentioned above are very Western-centric. Fortunately, the data was consistent for all demographics and geographies measured, as discussed above. The researchers also discuss this in the section titled "Strengths and Limitations of this Review".[1]

This is a major reason why we can't guarantee results for Africans or South Americans. We have absolutely no reason to believe their fruits are "inferior" (they are likely not), but there's no data to back it up, either.

Why are fruits and vegetables preventing heart disease death?

Now that we quite conclusively know the "what", the next question is the "why". Several times, the meta analysis' researchers suggest that further research is needed, but a few hypotheses are provided:

- Antioxidants and polyphenols from fruits and vegetables - like Vitamin C, carotenoids, and flavonoids - have been linked to lower cardiovascular disease rates. They're known to prevent cholesterol and other lipids from oxidizing in the arteries.[14]

- Concentrations of another group of antioxidants, alpha carotene and beta carotene, are also elevated when eating fruits and vegetables[15,16]

- Fruits and vegetables slightly decrease blood pressure[16,17]

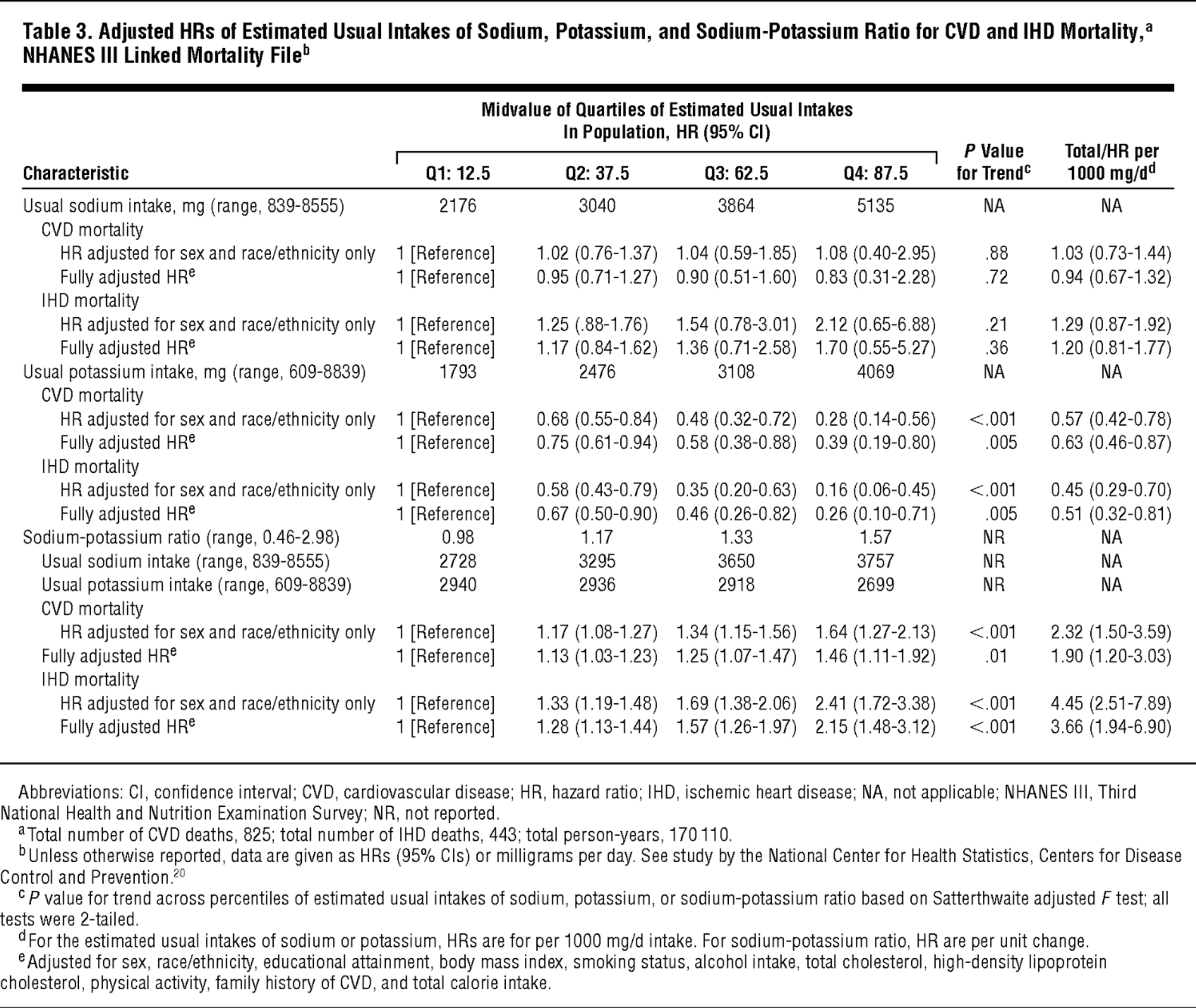

Get that potassium up! The lower your sodium-to-potassium ratio is, the more likely you are to die.[18] Fruits are high in potassium and will keep your numbers in check. Ratios are often more important than the numbers themselves.

Fruits and vegetables typically contain good doses of magnesium and potassium, both already linked to lower mortality rates[18-20]

- Vitamin C, carotenoids, lycopene, and other phytochemicals/phytonutrients (likely some that we haven't yet discovered) were explained as the success from one mortality study[21]

- Update: In a new 2016 meta-analysis, Berry consumption has been linked to significantly less type 2 diabetes mellitus, likely due to the dietary anthocyanin intake.[22]

From this, you can learn a few major points:

- Try as we may, we still don't really understand the deepest nuts and bolts of food. It's true that caloric intake is massively important (especially for body weight), but the basis for good health comes from something deeper than a simple caloric equation.

- There are likely still several compounds in our fruits and vegetables that we have not even discovered, let alone begun to understand.

- It's incredibly difficult to study, because of so many confounding influences and the difficulties of getting a human to properly self-report their diet.

Conflicting data: what about the British study on non-vegetarians vs. vegetarians?

The people out there who are actually "anti-vegetable" (and not just stubbornly lazy) often cite a British meta analysis of three studies which found very little difference between the mortality rates of vegetarians and non-vegetarians.

While some individuals are incredibly sensitive to some of the "plant toxins" in vegetables (such as the oxalates which cause kidney stones), using this study to fuel anti-vegetable sentiments is a bit of a stretch. Two major reasons why:

-

The healthy volunteer effect

Researchers in the British meta analysis noted that the mortality rates of both groups were below the national average. Since vegetarians and non-vegetarians basically covers a cross section of the entire population, how can that be?

It's called the "healthy volunteer effect".[23,24] This phenomenon basically states that the people most likely to volunteer for a study are already of a healthier (and potentially more well-off) demographic. After all, those who are already sick and more likely to die soon are less apt to join such a study.

Meanwhile, this same effect may damage the findings of the entire study we're discussing here, which is why it's nice to have over 800,000 participants, and some of the studies were taken randomly out of the general populace.

-

"Vegetarians" aren't necessarily eating vegetables. They're simply not eating meat.

Think about it. Are your vegetarian friends really eating a ton of fruits and vegetables, or are they just not eating meat? Without recording actual fruit and vegetable consumption, any "vegetarian study" is absolutely useless for our purposes here.

This is ripe for argument, but if you're in North America, think about the vegetarians you know. Do they really eat a ton of fruits and vegetables... or are they typically just stuffing themselves with grains and processed foods from a box?

In our personal experience, a large number of vegetarians could more reasonably be called "processed-food-etarians who just don't eat meat".

The British study fails to differentiate this because it didn't measure fruit and vegetable intake - making it massively ineffective compared to the rest of the data present on this page!

Granted, it's tough to make claims. But at this point, the most solid, abundant, and appropriately analyzed research ultimately indicates that eating fruits and vegetables will help you prevent incidences of cardiovascular disease, and if you're not getting those vitamins and minerals from bioavailable sources (such as nutrient-dense muscle and organ meats), you are worse off -- and likely to meet death sooner -- for not eating them.

What about cancer?

This is by far the most scary part of the research:

Eating fruits and vegetables has negligible difference on cancer mortality rates.

Some of the studies showed very minor reductions in cancer-based death when eating fruits and vegetables[25], but when looking at all of the data in whole, there's simply very little correlation, and other analyses back that up.[26]

It likely has little to do with organic / inorganic food

Unfortunately, increased organic food consumption has not been shown to prevent cancer. Relative risk of cancer incidence for 16 individual cancer sites and total cancer by reported organic food consumption. Stratified by age, region, and deprivation, and adjusted for smoking, BMI, physical activity, alcohol intake, height, parity and age...[27]

And while you organic food eaters are wisely nodding, thinking that the cancer in these fruit- and vegetable-eaters must have come from the inorganic pesticides used, think again: one very large study on women was unable to connect organic eating with a reduced incidence of cancer.[27]

In general (and unfortunately), the correlation between cancer and fruit/vegetable eating is weakest when it comes to the hormonal cancers: prostate and breast cancer are least affected by healthy eating.[1]

Preventing cancer is typically about less, not more

Our reasoning for this is simple: cancer is best prevented by removing negative factors, not by adding positive ones. Whereas adding fruits and vegetables to an existing low-quality lifestyle can improve your cardiovascular health, in terms of cancer, it is akin to putting lipstick on a pig.

Instead, reducing cancer risk is all about reducing exposure to known harmful carcinogens and other negative factors:

- Reduce overall food/caloric consumption[28-30]

- Don't smoke[31]

- Don't abuse alcohol[32-34]

- Don't drink contaminated water (most notably from petroleum, arsenic, asbestos, radon, agricultural chemicals, and hazardous waste)[35-37]

-

Preventing cancer isn't always about removing things, though. The one thing you can add to your life to reduce risk of cancer is exercise.

No trans fats![38,39] (ie any oils or fats with hydrogenated in the name, as well as margarine - the first study is about cancer, the second is about coronary heart disease - these oils bring the worst of both worlds)

- Reduce stress[40]

- Avoid air pollution[41-43]

- Avoid getting sunburnt. If necessary to be in the bright sun for long pereiods of time, use sunscreen / sunblock (or wear more clothing)[44,45]

- Be cautious with wireless / cell phone use and interaction with low-level RF / Microwave signals[46,47] (this one can be debated and is subject for more research, but the craziest part is that when you remove the studies that are funded by the telecommunications industry, things change really fast[48] and it starts to look a lot more dangerous to hold that cellphone up to your ear...)

One important thing you should add...

Preventing cancer isn't always about removing things, though. The one thing you can add to your life to reduce risk of cancer is exercise. Increased energy expenditure is linked to less likelihood of cancer.[49,50] Moderately hard / strenuous exercise is better than light exercise, too.[51,52]

Moderately hard / strenuous exercise is better than light exercise, too.[51,52] Pictured: @eatprayweights Becky

It's not exactly understood why, but the correlation between exercise and cancer reduction aren't even arguable at this point. In fact, the success of strict exercise programs in preventing prostate cancer (see the first source cited above) is so strong that researchers have moved onto the next step in the argument - determining how exercise works so well in this matter.[53]

Obviously, the cancer discussion and research analysis is out of the scope of this paper and the subject of volumes of books, so we'll leave it at that.

The point is, if you believe that you can simply eat lots of fruits and veggies and live cancer-free, the data unfortunately shows otherwise. There's just far more at play than diet alone -- but that doesn't mean preventing cancer is completely out of your control.

So where are we now?

At the end of the day, it's pretty simple: Don't eat your fruits and veggies while suffering from a Standard Western Diet, and statistically speaking, you will die sooner.

So it's mid 2016, and we've been through the ringer with diets these past few decades. Low-fat. Low-carb. Paleo. Gluten-free. Cleansing. Keto is on the rise. It never ends, and likely never will.

But let's take a time-out from all of that and talk about what we know. What really works per legitimate scientific research, if you actually stick to it.

Following are five bullet points to help guide you - the first three are about eating/dieting, the second two are for systematic support:

-

Eat five or more servings of fruits or vegetables per day

The basis of this article. At this point, if we haven't yet convinced you of this, then hopefully you're getting those nutrients from copious amounts of eggs, fish, and meat -- preferably organ meats.

Mix up those servings - don't just eat the same exact food all day long!

-

Calories are still king... when it comes to weight

Regardless of whatever diet is currently being shoved in your face, the research will never lie:

When it comes to body weight, the calories in vs. calories out equation is still the prevailing factor.

Sure, nitpicking can be made about different calorie sources, but in general, monitoring your caloric intake and not going to high (or too low) is still the most significant way to lose or maintain weight.

Don't believe us? See eight sources that back this statement up,[54-61] and there are definitely far more.

But as you may have noticed, we keep emphasizing the word weight. There's a reason for that, and it brings us to our next point:

-

...But when it comes to body composition, protein is the real king

The thing is, at a certain point, nobody really cares about your weight. Speaking from a straight man's point of view: if you're a woman, whether you're 110lbs or 125lbs is largely irrelevant to us. Seriously.

Eat more fish!!! At least two servings per week! The Western world does not get enough in, and it's yet another thing causing us cardiovascular problems.

In terms of attraction, what really matters is body composition - as in, a healthy muscle-to-fat ratio. There's no "set" ratio to go after for either gender, but consider some of the sexier athletes out there. In general, they're the ones who have both a reasonable-yet-limited amount of fat as well as a reasonable amount of muscle tone. Emphasis on the word "reasonable" -- not absurd amounts!

To achieve such a body, on top of performing resistance training (something not covered here, but something everyone should be doing), it's best to consume higher amounts of protein than the FDA guidelines generally recommend.

Several studies and meta-analyses demonstrate this:

- "the greater reductions in total and abdominal fat mass in women... on the HP (high protein) diet"[60]

- "PRO (high protein diet) was more effective in reducing percent body fat vs. CARB (higher carbohydrate diet) over 12mo weight loss and maintenance."[62]

- "Several meta-analyses of shorter-term, tightly controlled feeding studies showed greater weight loss, fat mass loss, and preservation of lean mass after higher-protein energy-restriction diets than after lower-protein energy-restriction diets. Reductions in triglycerides, blood pressure, and waist circumference were also reported."[63]

What kind of protein?

All kinds! Just like our fruits and vegetables, variety is the key to happiness and satisfaction.

You can get protein from chicken, turkey, fish, eggs / egg whites, beef, nuts, and dairy, which can include a scoop of your favorite protein powder here or there. You don't want to rely on supplements, but life becomes a whole lot easier when you can sneak in a good 40g worth of protein powder.

How much protein?

It depends on your goals and activity, really. When developing a diet, we typically calculate protein needs first, and then figure out how to make fats and carbs work inside of your caloric needs - but underestimating protein is a sin to your body composition.

In general, 1g of protein per pound of goal bodyweight each and every day is the base guideline. See your dietitian if you're obese, but if you're not too far from your goal weight, this is a good rule of thumb to start with.

-

Counting / Measuring Food Yields the Most Success

Counting calories is nothing new, and even predates modern computing. As early as the 70s, scientists began to realize that merely recording your behavior causes you to alter it for the better.[65] This was mostly applied to quitting cigarette smoking, but it didn't take long to apply it to weight loss as well.

A landmark study in 1993 performed on 48 women and 8 men showed that when subjects recorded their food, calories, and time eaten, they lost significant amounts of weight... but when they weren't monitoring it, they had weight gain![66]

This was done with good ol' fashioned pen and paper, and now with countless apps available with features like barcode scanning and daily notifications, there's really no good excuse for a serious dieter to avoid this.

There is no dispute that monitoring and counting calories and macros works, as meta-analyses show.[67] The biggest question really is how to get dieters to adhere it to this in the long-term... because let's be honest, it becomes a pain if you don't deeply ingrain it into a part of your daily life.

Our favorite app? MyFitnessPal.

-

Weigh yourself daily!

Even merely weighing yourself daily leads to achievement! A study performed in 1976 showed that subjects who didn't record their weight during the holiday season gained far more weight than those who did weigh themselves each day!![68] The goal was to simply "survive" the holidays without gaining weight - but many of those who weighed themselves each day in that study were able to lose it throughout that vicious period of time. This has been replicated in more frequent research as well.[69]

It's as true for health as it is for business and marketing: you can't manage what you don't measure.

At this point, you're probably thinking that we missed something huge - possibly the biggest argument to ever hit the Internet:

Low-Fat vs. Low-Carb???

So, this begs the question - who wins the holy war between low-fat and low-carb diets??

As we begin to allude up in the protein section above...

Low-fat vs. Low-Carb honestly doesn't matter much![70] Protein and calories are what matter first and foremost!

So as long as your protein is high and your calories are in check, you're best off doing what's best for you and your lifestyle.

This writer enjoys being on the lower-carb end of things (ie under 150 carbs per day), but every person seems to be a bit different. It also depends on your goals. If you're not sure, experiment with things over time, but do it within the five parameters listed above.

BROSCIENCE TIME: A new PricePlow Theory

We've come up with a small rule of thumb with respect to diet selection and strategy. However, let us warn you that we have zero scientific evidence to back it up, so take it for what it is:

-

When weighing food and counting calories and macros like a hawk, nearly anything from low-fat to low-carb to balanced-diet will work well.

In these situations, the calories and protein will be your main guide, and maintaining discipline trumps any diet quackery or trickery.

-

However, when not counting calories, "balanced diets" are total failures waiting to happen.

Unmeasured amounts of high-fat, high-carb foods displace too much of the good stuff in a diet. White potatoes aren't exactly quality "vegetables" either (yams, on the other hand, are far stronger sources of carbs)

Our broscience opinion on this is that when you have a "balanced diet", everything is on limits. This is bad for the mental state. We need at least some rules, or else we eventually slip into chaos.

Take for instance, a standard bag of potato chips. In any good low-carb or low-fat diet, it'd be off limits. But in a "balanced diet", it's fair game.. until you realize you've eaten 500 calories worth of chips and have received literally no nutrients or protein. Now your day is potentially bombed and you need to be perfect and hit the gym extra hard to undo it.

The point being, foods that are both high-carb and high-fat are diet devastators when not using a food scale and calorie counter. But they're simply not even allowed when on a low-carb or low-fat diet, so in those cases, they wouldn't be in your pantry anyway.

Further theorizing: why balanced diets don't stick

Looking at the "potato chip" point a bit deeper, consider this: there aren't too many foods found in nature that are both high-fat and high-carb. It's usually one or the other, with a few exceptions. Perhaps it's best we didn't mix carbs and fats as often as we do?

We love to write about supplements here, but what is the point if we're not going to get with the basics and eat our fruits and vegetables?

It's not that these two things are necessarily bad, it's that they waste space for the things that are better. After all, eating too much of these empty foods almost universally causes us to neglect our fruits, vegetables, and protein - the three most major keys to dietary health success.

So in our opinions, if you're not monitoring, pick one or the other... but we still urge you to count your calories, and if you're low-carb, find a way to fit those fruits in!

Give me veggies or give me death

At the end of the day, it's pretty simple:

Don't eat your fruits and veggies while suffering from a Standard Western Diet, and statistically speaking, you will die sooner.

Choice is yours.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)