Unless you've been living under a rock, you've likely heard of Ozempic (semaglutide) by now.

Is Berberine "Nature's Ozempic"? We take a look at their mechanisms as GLP-1 agonists, and answer, "Yes, somewhat." This article compares and contrasts the two.

This fat loss drug has taken the mass media by storm, thanks to testimonials (and speculated use) by a number of celebrities in film, television, and modeling. Proponents claim it's the miracle weight loss pill the world has been waiting for.

We have to admit, the clinical trials look pretty good on the surface. One study reports Ozempic can cause weight loss of 4% to 6.2% body mass in diabetics, with an even more impressive effect size of 6.1% to 17.4% in non-diabetics.[1] Another reports that after 68 weeks of weekly treatment with Ozempic, 86.4% of participants lost 5% or more of their body weight, and 69.1% lost 10% or more.[2] These are pretty serious numbers; shedding 10% or more of your body mass can be life-changing.

When something like this is invented (or discovered), it's common to look for natural alternatives in the dietary supplement industry, especially those that have a longer history of safe use. In the case of Ozempic, berberine is the ingredient that many have compared it to.

So in this article, we discuss the mechanisms behind Ozempic, and if berberine shares those same mechanisms.

How Ozempic Works: GLP-1 Agonist

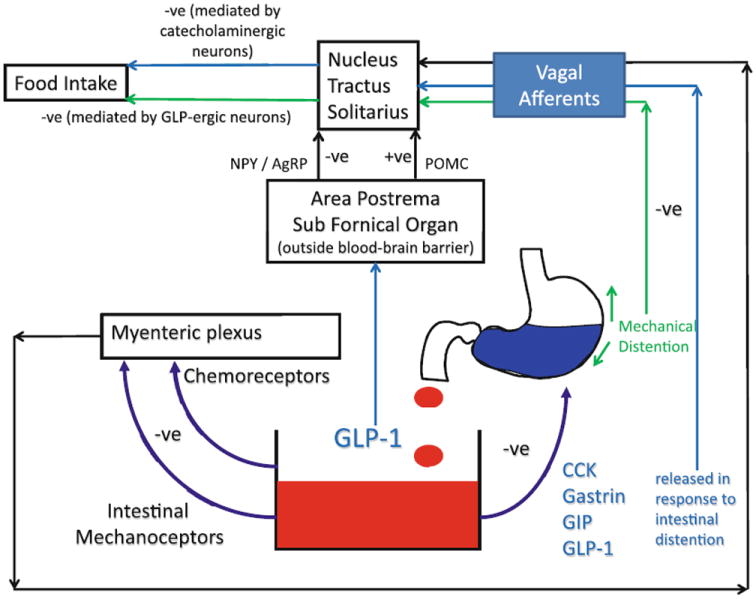

Despite the hype surrounding Ozempic, its mechanism of action is not novel. Medical science has known for decades about its target, the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R).[1,2] More specifically, it's a GLP-1R agonist – it activates the receptor, rather than inhibiting it. The basic reason GLP-1R agonism works for weight loss is that GLP-1 regulates appetite.[3]

Not only does GLP-1 affect appetite signaling in key brain regions, potentially helping discourage compulsive eating, it can also have a mechanical effect on your feeling of satiety by delaying gastric emptying.[3] By keeping your food in your stomach longer, you feel fuller longer (in the inset graph, it's called "mechanical distention").[3]

Pretty cool, right? Well, Ozempic's GLP-1R agonism is certainly not unique. It probably won't surprise you to learn that several other compounds — some of them nutritional supplements — act on GLP-1R as well.

So what's the deal? With other GLP-1R agonists already out there, does Ozempic really deserve all the attention it's getting?

Berberine: Nature’s Ozempic?

A study published in July of 2023 suggests that berberine is one of those other GLP-1R agonists.[4] This study has been making the rounds on social media, leading many prominent influencers, both inside and outside the supplement world, to ask: is berberine nature's Ozempic?

Today, we want to take this opportunity to answer: Yes, at least partially, berberine is like "nature's Ozempic". Of course, they're not exactly the same, and we're not claiming that berberine is more effective than Ozempic – but for some use cases, we're not going to claim it's less effective, either.

Instead, let's lay out some evidence, and let you be the judge. First, what is this molecule found in numerous dietary supplements?

Berberine, a natural plant alkaloid, has been a supplement industry mainstay for over a decade, thanks to its powerful anti-diabetic effects[5,6] that can lead to healthy weight loss.[7,8] Our most in-depth coverage on the ingredient is in our article titled Berberine: The Best Glucose Disposal Ingredient Just Got Better, which introduced the world to dihydroberberine, a more effective form of the ingredient discussed later.

But for now, stay on this page, get a brief overview on berberine, and let's dig directly into the GLP-1 question:

Nature’s best glucose disposal agent

As the title of the article linked above suggests, berberine is often used as a glucose disposal agent,[9] since it helps improve the body's utilization of glucose. The alkaloid improves the shuttling of blood sugar out of the blood and into cells - preferably muscle tissues in someone who exercises.

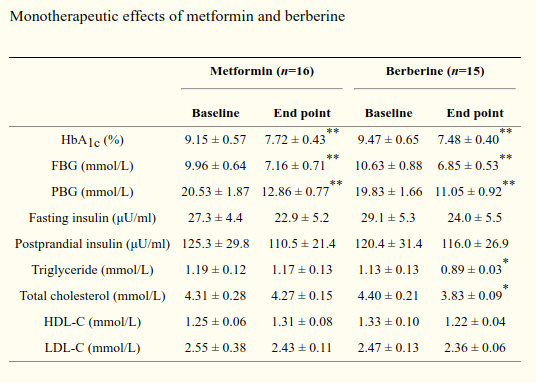

One could very easily argue that berberine outperformed metformin in most measures![10] But at this dose, there are some concerns to address, which are covered later on in this article.

This provides an anti-diabetic effect by supporting greater insulin sensitivity, which is important because insulin resistance -- caused by our processed foods, toxic environments, and lack of physical activity -- is highly connected with our ongoing societal metabolic syndrome.[11-13]

When it comes to these mechanisms, we have to bring up the study where berberine outperformed common antidiabetic drug metformin -- with fewer side effects.[10] The authors of that study note that "berberine exhibited an identical effect in the regulation of glucose metabolism" (as measured on HbA1c and blood glucose levels when fasted and after eating), it even regulated lipid metabolism more than metformin.

So realize with this GLP-1 / Ozempic hype that this isn't the first time berberine has been compared to a pharmaceutical drug.

However, there's more to berberine than just its insulin sensitizing effects. It turns out the GLP-1 mechanism is at play too:

Berberine – GLP-1 agonist

The research community has known since 2009 -- and perhaps longer -- that berberine is a GLP-1 agonist, promoting GLP-1 amide secretion.[14] A series of research studies through the 2010s then repeatedly, successfully, and safely demonstrated these effects in preclinical trials - both in vitro and in vivo.[15-17]

While the new study published recently in 2023 adds to the knowledge base, it's a study published in 2019 that provides the most valuable insight explaining what we meant by the phrase anti-diabetic up above.[15] This is the study we'll focus on, but the other studies cited above can be read for more background.

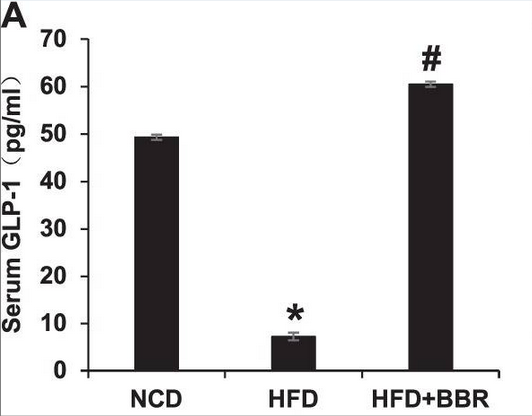

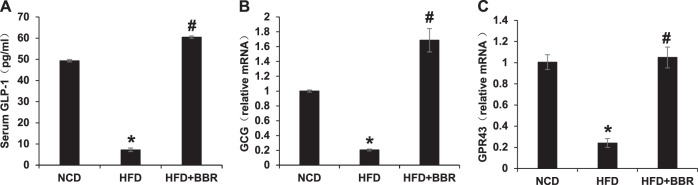

In this experiment, researchers induced diabetes in mice by feeding them a high fat diet (HFD) for 16 weeks.[15] At the end of this feeding period, half the HFD-fed mice were randomly assigned to receive berberine. A third group of lean, healthy mice served as the non-berberine control set.

When the researchers compared the three groups, they found that the enterocytes (intestinal cells) of the non-berberine HFD group secreted significantly less GLP-1 than the healthy controls.[15]

This isn't surprising since GLP-1 downregulation is a known feature of diabetes.[18,19] Impaired GLP-1 secretion and signaling is a huge problem for anyone, but particularly a diabetic. Over time, the overeating encouraged by GLP-1 downregulation can exacerbate the underlying metabolic dysfunction of diabetes, causing the disastrous negative feedback loop that so many overweight individuals have found themselves dealing with.

...but berberine restores GLP-1!

What's remarkable, however, is that berberine treatment restored GLP-1 secretion in the HFD-fed mice.[15]

A closer look: In diabetic mice, berberine treatment actually enhanced GLP-1 signaling, increasing it to above baseline.[15]

What's even more impressive is that the berberine-treated HFD group actually had a higher serum GLP-1 level than the lean, healthy controls![15] So berberine didn't just reverse the diabetes' effect on GLP-1 signaling, it actually left the mice, at least with respect to GLP-1 signaling, better off than before.[15]

As an interesting side note, GLP-1 seems to do this at least partly by activating bitter taste receptors.[16] So black coffee fans the world over can rejoice – you've been (at least slightly) vindicated by this branch of science.

Taste receptors are just part of the story, though. There's a much more interesting part, and it has to do with mitochondria, one of our favorite subjects here on the PricePlow Blog.

Berberine restores enterocyte mitochondrial function

By the end of the study, mice in the HFD, non-BBR group had roughly twice as much ATP just hanging out in their intestinal tissue, compared to the other two groups. At first, this might sound like a good thing – who doesn't want more ATP? It's the "energy currency" molecule, right? But, as is often the case in biology, it's not necessarily that simple.

Berberine treatment increased ATP consumption in the mice's intestinal tissue, which implies a restoration of normal mitochondrial respiration.[15]

As it turns out, ATP overproduction can be caused by eating too many calories, as in a high fat diet. This is something that should make intuitive sense – your mitochondria turn calories into ATP, so if you eat too many calories, then logically we would expect your mitochondria to make too much ATP. And, in fact, this is exactly what happens in the intestines.

What happens next is pretty ugly. That extra ATP sets in motion a chain of events that increase mitochondrial oxidative stress, and ultimately destroys the electrical membrane potential that mitochondria need for normal respiration. This leads to mitochondrial damage -- in this case, in cells of the digestive system.[15]

This process of mitochondrial damage through energy overproduction is referred to as mitochondrial overheating.[15]

Berberine protects against this mitochondrial overheating

Fortunately, berberine actually protected the mice's mitochondria from that damage by decreasing ATP production, even in the presence of the extra caloric energy![15] Hence, the title of the study we've been discussing, "Berberine is associated with protection of colon enterocytes from mitochondrial overheating".[15]

So, it seems that a huge part of berberine's overall benefit comes from restoring mitochondrial function – a common theme among the best nutritional supplements.

What about in humans?

Evidence of berberine's GLP-1 agonism in humans remains preliminary. A 2021 randomized controlled trial did find increased GLP-1 activity in subjects taking berberine, but could not determine if berberine caused the effect directly or indirectly.[20]

However, as an editorial opinion, we offer that the above preclinical research is pretty good support for a berberine-driven effect - especially since we're already quite familiar with berberine's other incredible effects in humans.

Other Similarities: Increased Insulin Secretion... (sometimes)

Berberine is a natural plant alkaloid shown to improve glycemia / glucose disposal and lipids by boosting insulin sensitivity. One of its mechanisms is through GLP-1 activation

There's another similarity between berberine and semaglutide (the unbranded chemical name of Ozempic), but they don't always behave the same. Semaglutide is an incretin mimetic that increases insulin secretion,[21] and berberine usually increases it as well.[6,22-25] However, there are at least a couple of studies where berberine decreased insulin secretion.[26,27] Why isn't it as consistent in this fashion?

The difference seems to be that berberine increases high-glucose dependent insulin,[6,25] meaning that it's more effective when glucose is present. Case in point, in the two studies where serum insulin levels were lower, the blood tests were taken in a fasted state.[26,27]

Semaglutide, however, seems to more reliably increase insulin secretion, even in a fasted state while the dieters are eating less.[28] Normally, this would be a concern, since insulin can be considered the "energy storage hormone", but its appetite suppressive properties (due to delayed gastric emptying) tilt the scales towards more weight loss -- the point where it's become more than just antidiabetic drug.

On the other hand, berberine's effect may actually be what many of our readers researching sports nutrition want, since they're attempting to keep carbohydrate intake high for performance and muscular hypertrophy reasons, but may not always want insulin circulating at other times of the day. Elevated insulin does, after all, reduce fat oxidation,[30,31] so timing the hormone's release should be taken into account by those trying to effectively burn fat.

Ultimately, this means that berberine's effects as an insulin secretagogue will be diminished on lower-carbohydrate diets (although the GLP-1 mechanism is still in play). It will undoubtedly be most effective in diabetic / prediabetic populations, with some great use cases for carbohydrate lovers. This may be great news, depending on your situation.

Berberine’s other benefits

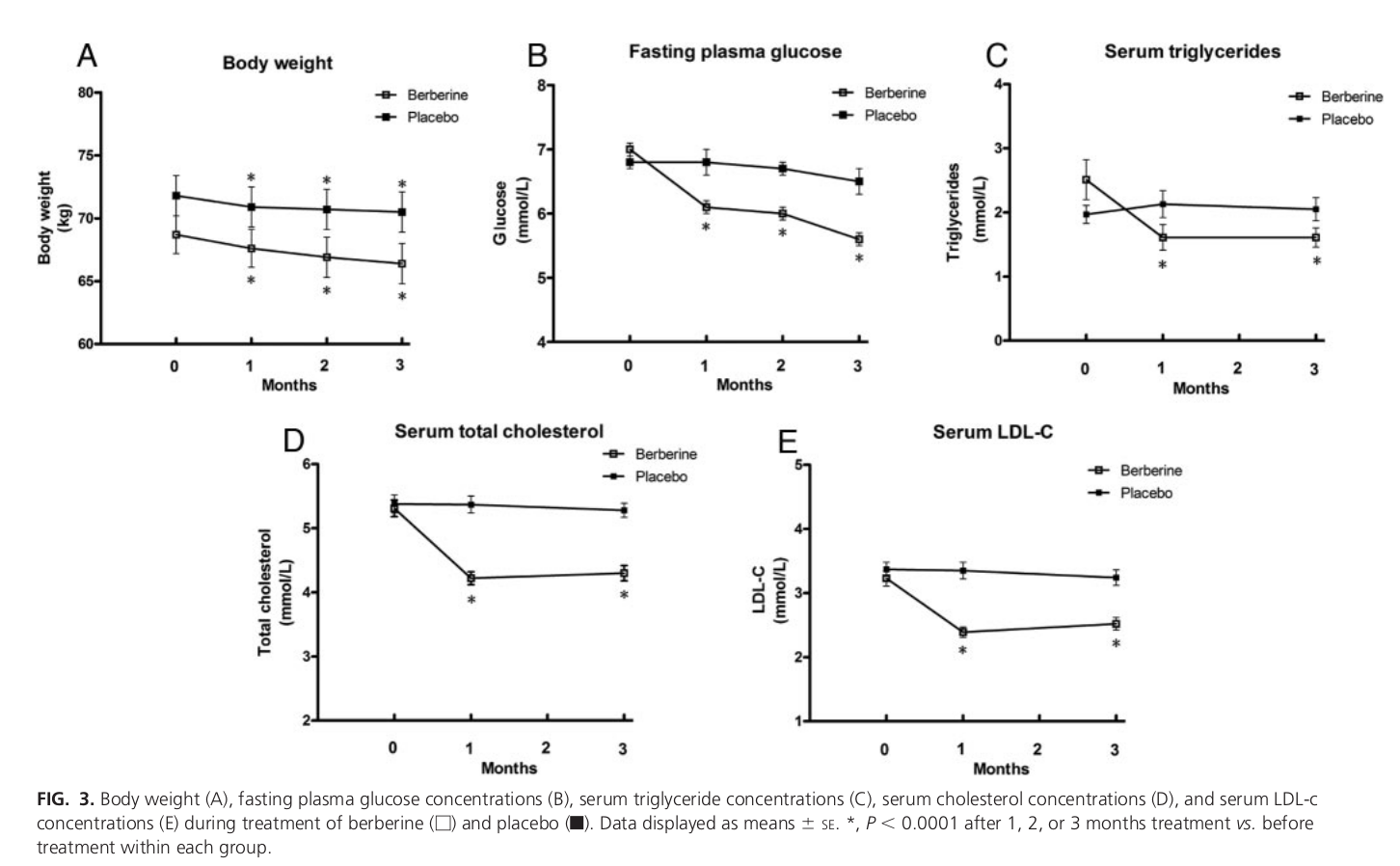

Additionally, there's research in humans demonstrating berberine's other anti-diabetic benefits.

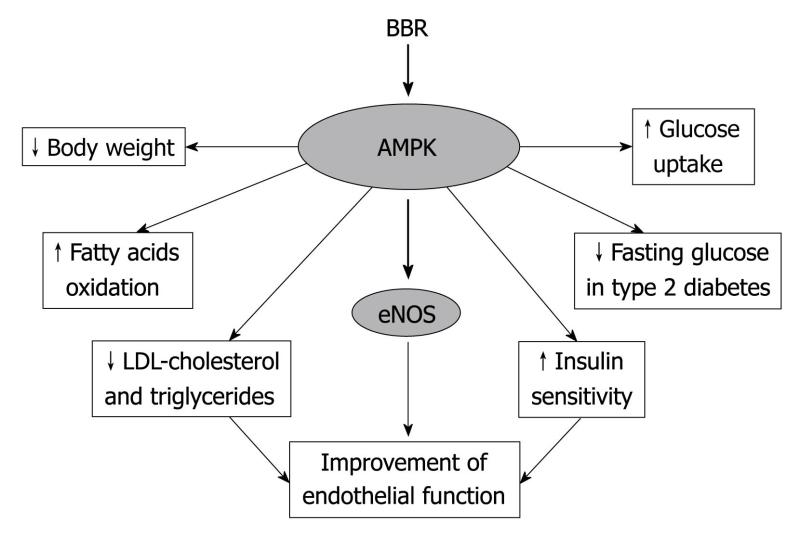

For example, when berberine is taken with a meal, it has been shown to significantly decrease peak blood glucose levels.[9,32-34] The mechanism of action seems to be promoting cellular glucose uptake by activating an enzyme called adenosine monophosphate kinase (AMPK).[35,36]

Berberine also seems to have favorable effects on blood cholesterol and triglycerides, which is to be expected since AMPK promotes fat uptake as much as glucose uptake.[37]

Berberine is possibly the most underrated supplement in the world. It creates a fantastic series of metabolic reactions that every carb-user should know about.

Other studies have found that berberine can[9,32-35,38]:

- Inhibit gluconeogenesis[36]

- Prevent the absorption of dietary carbohydrates[36]

- Improve microbiome health[39]

- Decrease oxidative stress[40]

- Reduce systemic inflammation[40]

Nature’s metformin

Wrapping up our discussion of berberine and metabolic health, we want to remind everyone of the study where berberine metformin in terms of glycemic control for type 2 diabetics.[10]

So, as long as we're asking, "Is berberine nature's Ozempic?", we should also ask if berberine is nature's metformin. The answer to that question is also a probable yes, but that's the subject of another article.

As it stands right now, it seems that Ozempic / semaglutide is more powerful than berberine as a GLP-1 agonist, while berberine (when dosed well enough) can compete with metformin in terms of glycemia and lipids.

Berberine and weight loss

Now for the big one, and the reason most people are here. One human study found that, on average, 500 milligrams of berberine, taken orally for 12 weeks, produced a 2.3% reduction in weight.[10]

Admittedly, this is a smaller effect size, but the study duration was also shorter than what we've seen in Ozempic clinical trials.

The other thing to note is that berberine-driven weight reduction came with a 1.1% decrease in waist-to-hip ratio, and a 3.6% decrease in body fat percentage – strong indications that berberine is torching fat, not muscle or bone mass.[10]

Meta-analyses of berberine literature have found similar results, with similar effect sizes.[41,42]

Here's the thing, however. There's a way to make berberine even better -- both in terms of potency and reducing its downside of requiring a relatively large 1.5 gram daily doses for maximum effects.

GlucoVantage Dihydroberberine – A Better Berberine

Could berberine be made even more effective for weight loss than we saw in that 12 week study?

We think the answer is yes – According to the meta-analyses we cited, some studies used doses ranging from 1,000 to 1,500 milligrams a day and saw better results.

Why, then, is berberine not more often touted as a miracle weight loss supplement? (Aside from the Spring/Summer 2023 TikTok craze, of course.)

Berberine at clinical doses has GI consequences!

The answer is that such large clinically-verified doses of berberine come with problems. For example, in the study we cited where berberine went up against metformin, 35% of subjects had significant gastrointestinal upset when taking the 1,500 mg/day dose (three capsules worth).[10]

That's a pretty big incidence rate. If we want berberine to compete with something like Ozempic, researchers need to find a way to increase the dose, increase the potency/bioavailability, and reduce those side effects.

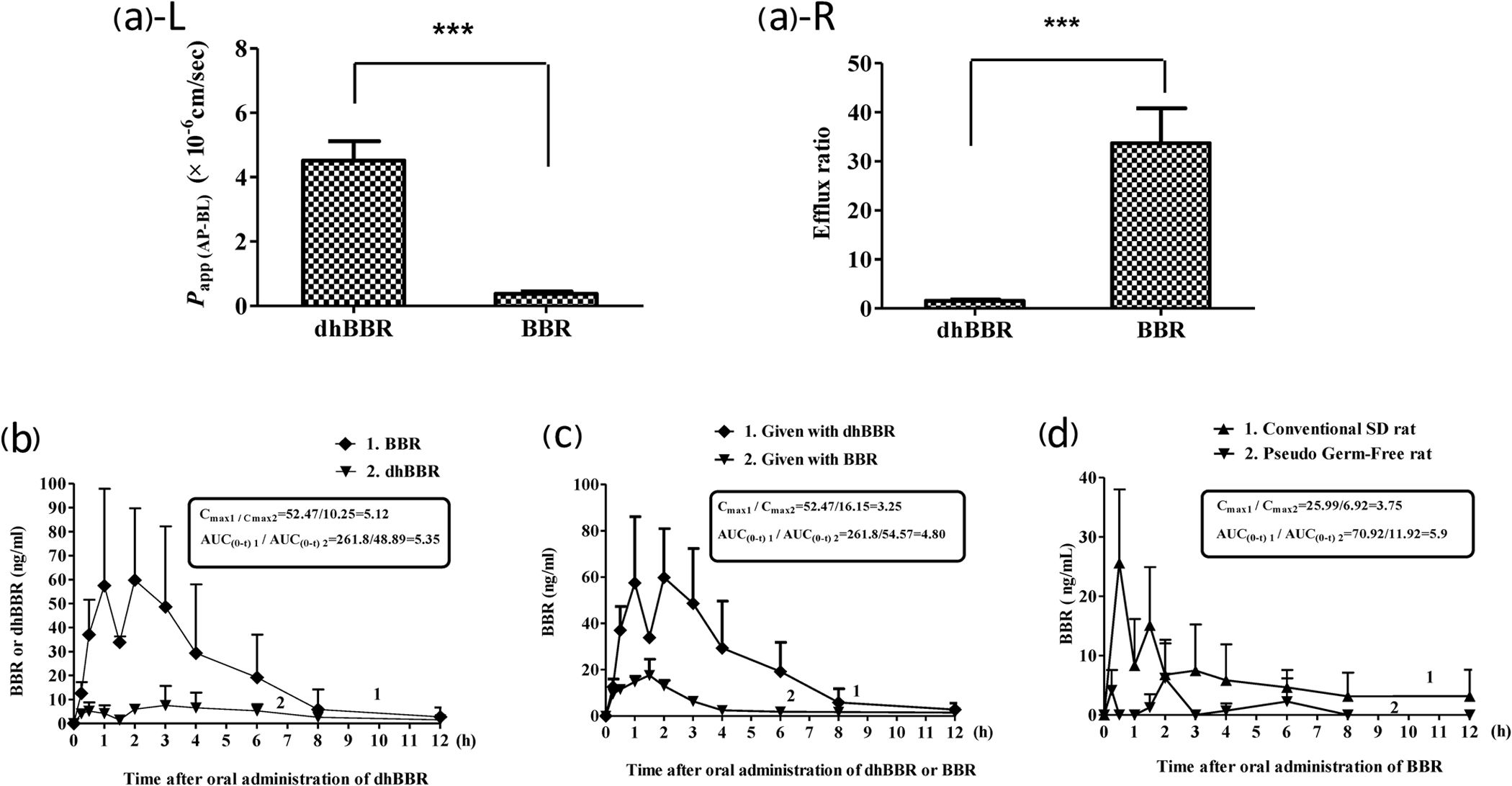

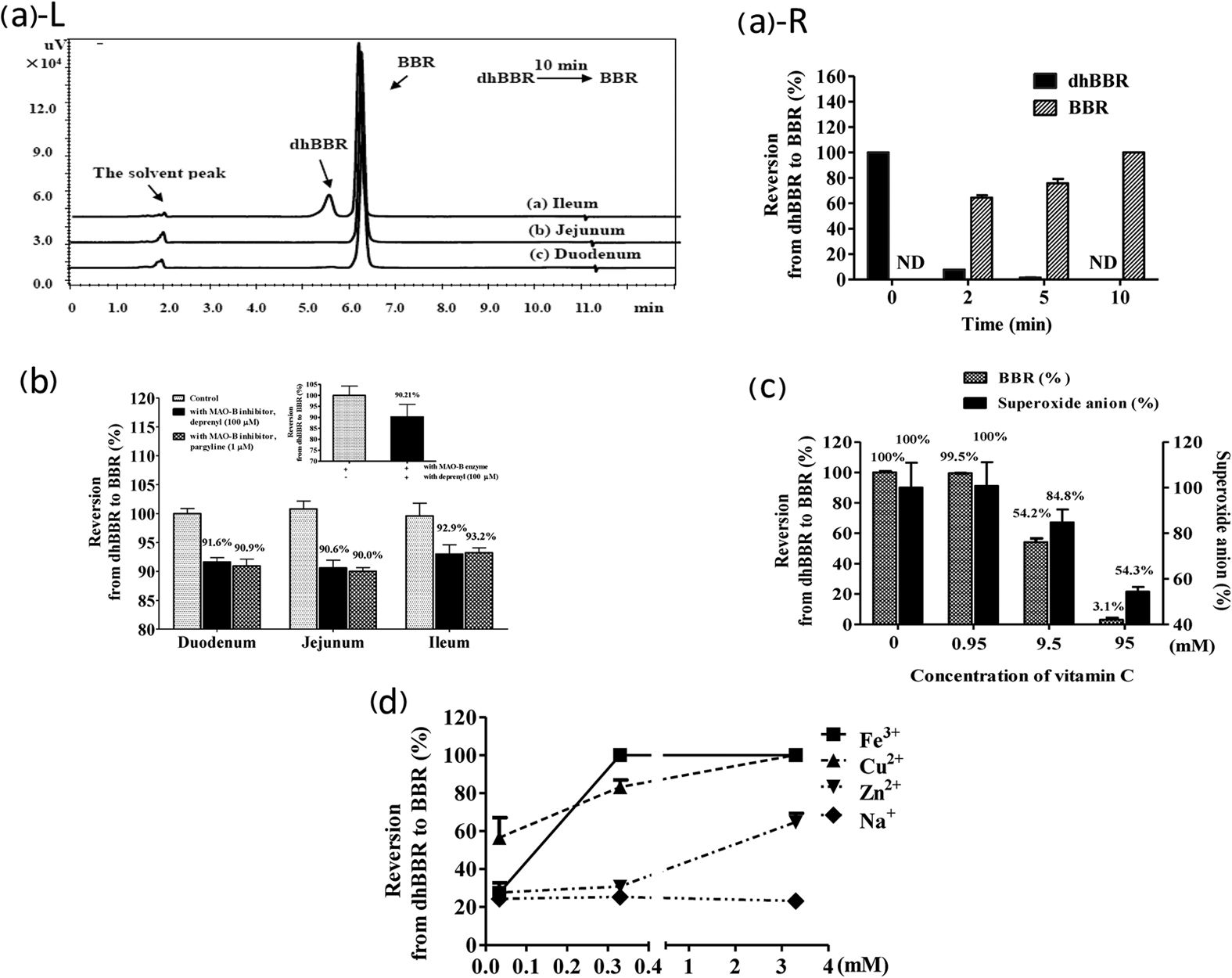

We've long said that GlucoVantage dihydroberberine has 5x the bioavailability if traditional berberine.[43]

That's where dihydroberberine, sold as GlucoVantage by NNB Nutrition, comes in.

Dihydroberberine (DHB) is much more bioavailable than ordinary berberine and achieves similar effects at vastly smaller doses.

As its name suggests, DHB is produced by adding a hydrogen ion to the berberine molecule - which is something your body was going to do anyway! Reason being, dihydroberberine is naturally made in the human digestive tract as a berberine metabolite -- it's produced when the gut microbiome hydrogenates berberine so that it can absorb it.

The reason gut flora convert berberine into DHB is because, unlike berberine, DHB can pass through intestinal tissue, which enables it to reach the bloodstream. Once it's in the blood, DHB gets converted back into berberine, whereupon it has the cool, anti-diabetic effects we've been talking about.[43]

Here's a simple diagram of berberine's digestive process:

Berberine (gut) → dihydroberberine (intestine) → berberine (bloodstream)

As it turns out, that first conversion step is a bottleneck in this entire process. That's why large doses of berberine cause GI upset: gut flora typically can't convert it into DHB fast enough to prevent irritation. This is especially true of people who need berberine the most – individuals with diabetes or pre-diabetes typically have poor gut health and reduced microbiome diversity.[44]

Because DHB sidesteps the conversion bottleneck, it's 5 times more bioavailable than standard berberine.[43] (You can read our article titled 5x More Bioavailable: Why Dihydroberberine is "The Better Berberine" for more information on that study).

DHB's beneficial effects also last longer than those of ordinary berberine.[45,46]

Research shows that DHB can provide the same benefits as berberine, with a much smaller dose:

- Improved glucose uptake, particularly in diabetics[10,47]

- Increased insulin sensitivity[48]

- Improved glucose utilization by muscle cells[49,50]

- Better body composition[10,51]

Want to learn more? Read our GlucoVantage / Dihydroberberine content

The reason you don't hear as much about dihydroberberine is because it's more expensive to manufacture, and too many dietary supplement companies unfortunately take the cheaper route. Dihydroberberine is patented[52] and sold as GlucoVantage from NNB Nutrition, which is the primary way to get it. But at a lower cost, it's also a lower dose.

Simply put by the researchers: "DhBBR [Dihydroberberine] has a better intestinal absorption than BBR."[43]

We wrote about GlucoVantage DHB in our article titled GlucoVantage: Dihydroberberine for Superior Insulin Sensitivity. NNB Nutrition is a partner of PricePlow's and a sponsor of this article, but we're being honest when we say we've seen work tremendously for blood sugar control and weight loss.

The effective Dihydroberberine Dosage is 30% the dose of standard berberine, giving it far more applications and less GI discomfort!

If you'd like to try GlucoVantage on its own, check out Alpha Lion's Gains Candy GlucoVantage. Despite the name, which admittedly may be a bit off-putting to those who don't know the lighthearted Alpha Lion brand, this is a trusted and tested form of GlucoVantage that allows you to try it alongside the rest of your diet regimen.

We do not, however, encourage anyone to take berberine or dihydroberberine alongside Ozempic or other GLP-1 agonists.

Click through if you want to learn more about this amazing, pro-metabolic supplement, but please read our conclusion first, because we want to emphasize protein consumption before leaving.

Some closing thoughts

It's clear that Ozempic is making massive waves throughout the world. So much, in fact, that we're seeing the entire fat burner category of dietary supplements shrink at retailers -- stores are beginning to dedicate less shelf space to weight loss because of this drug. This is the stark reality, the drug class is obviously achieving results.

With that said, we still love berberine (and dihydroberberine) because of its greater body of research and longer history of safety. It's not yet clear what long-term pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonist drug use looks like from a safety perspective.

Keep protein high no matter what you do!

Some of the common criticisms of Ozempic (aside from increased risk of thyroid cancer[53]) are that it may lead to muscle wasting[54,55] and weight gain returns once discontinuing the drug.[56] However, if we're being honest, those same things can happen with berberine use!

Reason being, a large portion of these effects are through appetite suppression. And with that, if one does not manually intervene, comes a natural reduction in protein intake. We don't need to remind our readers that regardless of what diet you choose, a high protein:energy ratio must be maintained - above all else!

We can argue about various toxic processed oils, herbicide-laden carbohydrates, and the other fat-soluble molecules in our diets that drive insulin resistance all day long, but regardless of where you stand on those, or whether you're into low-fat or high-fat dieting, you must keep protein high.

Our hope is that research on both berberine and Ozempic will be published showing successful DEXA scans that maintain muscle tissue with high-protein diets, and when that's the case, we'll be a bit more confident in the more aggressive interventions. However, we still have concerns for long-term high insulin secretion, which seems to be more of a concern with Ozempic than berberine.

Until there's more long-term data, we urge extreme caution, and always suggest lifestyle change over all else. After all, regardless of whether it's a dietary supplement or pharmaceutical drug, you don't want to be on a weight loss intervention for the rest of your life.

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

Alpha Lion Gains Candy GlucoVantage – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)