If one surveys the current state of the supplement market, they'll find lots of testosterone boosters and recovery aids aimed at male athletes – but not nearly as many well-formulated hormonal supplements made specifically for women.

Animal Alpha F: For serious women who need more

Animal Alpha F is a comprehensive women's support supplement for hormonal balance, mood / stress relief, bone / joint support, complexion care, and more!

Universal Nutrition has set out to rectify this imbalance with their Animal Alpha F, a female-targeted comprehensive wellness supplement. All in one "Pak" (a nod to the legendary Animal Pak multivitamin packs), Alpha F provides the following complexes:

- Hormone balance

- A premier form of collagen

- Mood & stress support

- Bone & joint health blend

- Complexion, hair, skin and nail care

- Absorption / bioavailability booster

Women have many needs, and they can be addressed by numerous ingredients. The best way to do this is to pack them in -- and that's with Universal Nutrition's famous "paks", which contain multiple capsules in one convenient serving.

The science of each ingredient is covered below, and you can check prices using PricePlow's price comparison tool:

Universal Animal Alpha F – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming Ingredients video.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Animal Alpha F Ingredients

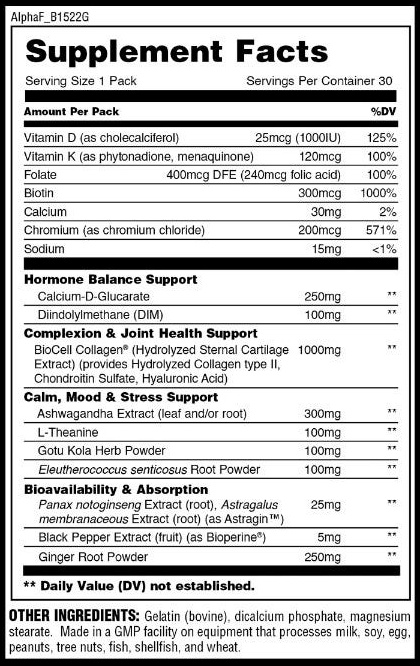

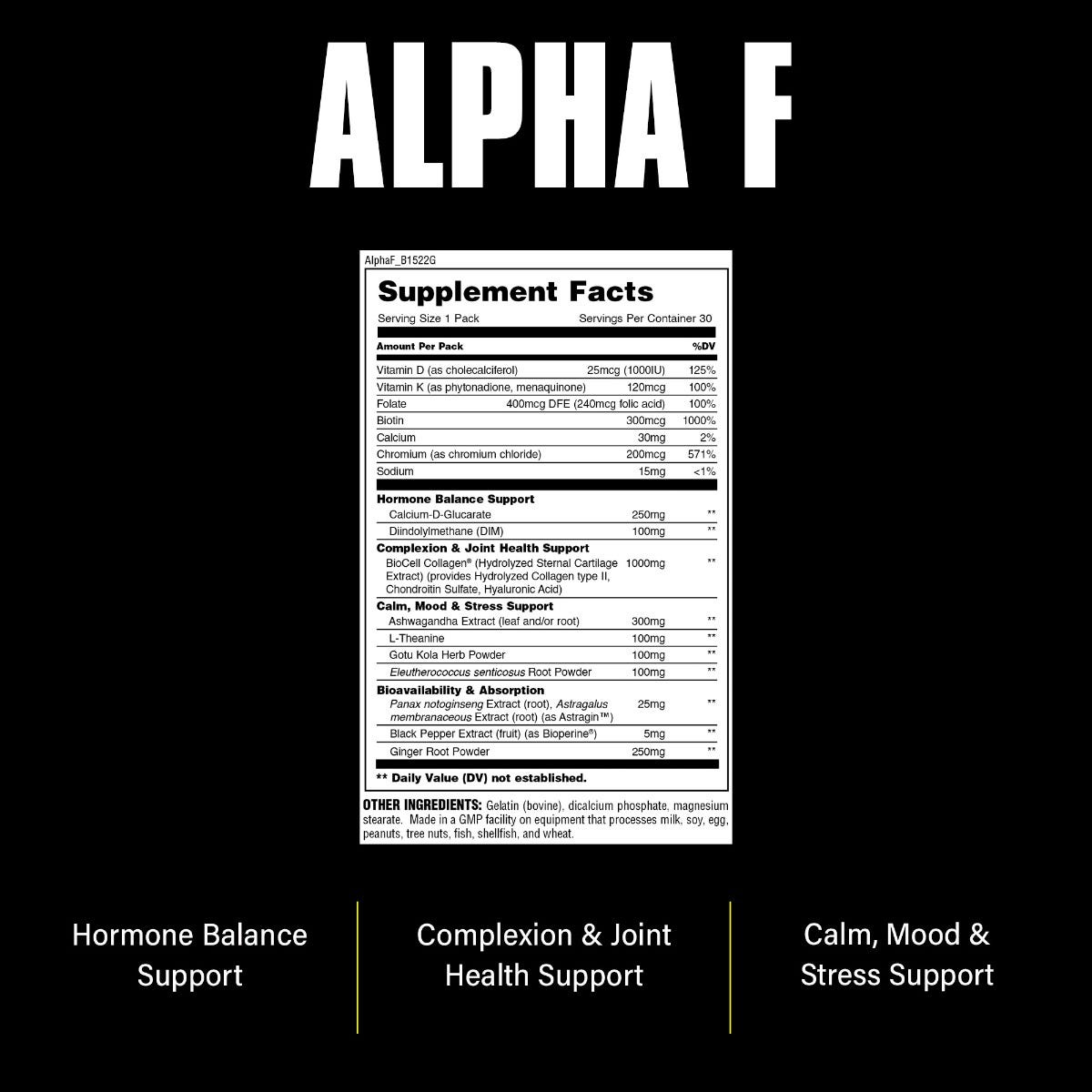

In a single, one-pack serving of Alpha F from Universal Nutrition, you get the following:

-

Hormone Balance Support

All of us—men and women alike—need some estrogen for optimal health[1] – and in the right balance. However, in some people, enzyme aromatase, which converts testosterone to estrogen, can become overly active, feeding into a syndrome called "estrogen dominance" where, you guessed it, you're left with too much estrogen.

Estrogen dominance can be pretty bad news. Aromatase overexpression and estrogen dominance have been correlated with serious disease, including certain forms of cancer.[2]

One common cause of aromatase overexpression is obesity[3] – a very common condition in the United States, and other industrialized countries, too. The more body fat you carry, the more active your aromatase system will be.

When it comes to women's health, breast cancer proliferation is perhaps the most infamous consequence of estrogen dominance.[4] In fact, pharmaceutical-grade aromatase inhibitors— drugs that prevent aromatase from producing estrogen—are one of the most common treatments for breast cancer.[5]

Aromatase inhibitors work because they decrease the amount of circulating estrogen in the body.[5]

Furthermore, the modern environment is loaded with xenoestrogens – compounds (usually synthetic) that mimic the action of estrogen closely enough to increase the body's overall estrogenic load for some people.[6]

The idea behind this two-ingredient hormonal balance blend is basically to decrease that estrogenic burden.

-

Calcium-D-Glucarate – 250 mg

Calcium D-glucarate is a combination of glucaric acid and calcium. It occurs naturally in the body in small amounts and participates in a process called glucuronidation, a detoxification process by which the liver eliminates toxic compounds from the body.[7]

The steroid hormones, which include testosterone, estrogen, and their metabolites, are eliminated from the body via glucuronidation.[8]

Calcium D-glucarate inhibits beta-glucuronidase, an enzyme that interrupts glucuronidation by breaking down glucuronic acid. High beta-glucuronidase activity is associated with hormone-dependent cancers,[9] such as breast cancer.

When it comes to the estrogen system, beta-glucuronidase reactivates estrogens, which leads to the absorption of free estrogen by the body's tissues.[10]

So in other words, by inhibiting beta-glucuronidase, calcium D-glucarate encourages the glucuronidation of estrogen.

Calcium D-glucarate synergizes with the next ingredient we'll discuss, DIM – whereas DIM helps reduce estrogen production, calcium D-glucarate helps the body efficiently dispose of whatever estrogen it's already produced.

-

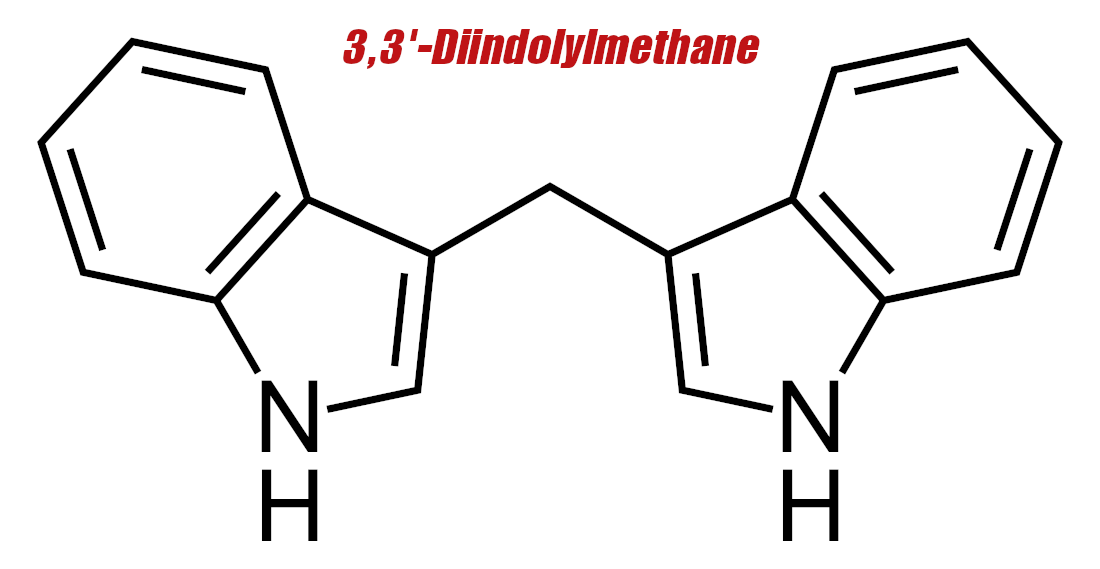

Diindolylmethane (DIM) – 100 mg

Now that we know how aromatase works, we can discuss diindolylmethane (DIM), a potent aromatase inhibitor.

A preliminary body of research shows that DIM can impair the proliferation of estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells in vitro.[11]

One theory as to how DIM does this is that it has an affinity for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which, when activated, downregulates (decreases the density of) estrogen receptors.[12-14] By activating AhR, DIM basically makes estrogen less active in the body.[15]

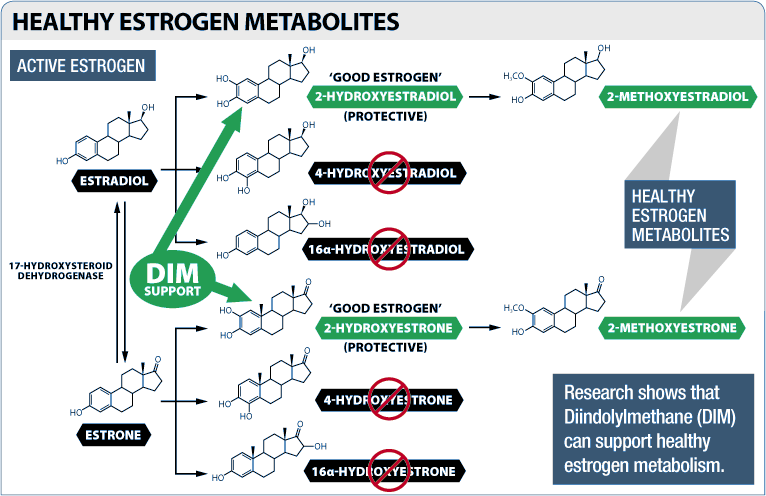

But beyond its ability to prevent androgens (testosterone and its metabolites) from being converted into estrogen, DIM also shifts the body's balance toward less harmful forms of estrogen.

Three main forms of estrogen are found in the human body – estrone, estradiol, and estriol. Estradiol is the strongest, which means that it has the highest level of activity at the cellular estrogen receptor.[16]

When these three forms of estrogen are metabolized by the body, a few different estrogen metabolites are produced as a byproduct, including estradiol-2-hydroxylase (EH) and 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone.[16]

Most researchers regard these 2-hydroxylated forms of estrogen as being "good" estrogens because of their beneficial impact on human health.[17,18] In fact, the ratio of 2-hydroxylated metabolites to 16-hydroxylated metabolites is used as a measure of hormonal health.

Having more "good" estrogen, i.e. more 2-hydroxylated estrogen, is correlated with higher amounts of muscle mass and lower levels of body fat.[19]

So why is this important for us? In 2012, researchers found that DIM affects the enzymes that convert estrone to hydroxyestrone,[20] increasing 2-hydroxylates while decreasing 4-hydroxylated and 16-alpha-hydroxylated estrogens.[20-23]

-

-

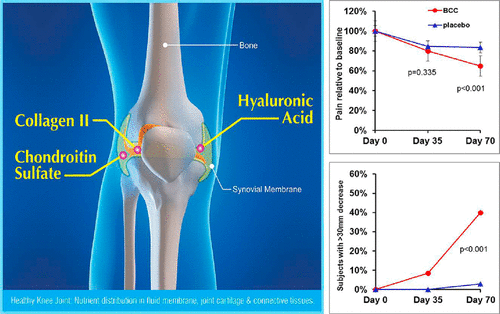

BioCell Collagen – 1000 mg

The sole component of the Alpha F's Complexion & Joint Health Support section, BioCell Collagen is a trademarked blend of collagen type II peptides, hyaluronic acid, and chondroitin sulfate that's extracted from hydrolyzed sternal cartilage.

Type II collagen is especially important for the health of joints and connective tissue – a big concern as we age, especially for those of us who wish to remain physically active. The hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate are here as collagen and cartilage precursors, respectively.

BioCell Collagen is made of collagen type II peptides, hyaluronic acid, and chondroitin sulfate, giving it an incredible range of benefits.[24]

Human clinical trials of BioCell and similar collagen extracts (i.e. rich in type II collagen) have found that supplementation with these compounds leads to improved mobility, increased physical activity, and a reduction in chronic pain, particularly in study subjects' joints.[24-26]

Researchers have also found that BioCell decreased the recovery time needed after resistance training, and improved biomarkers for tendon and ligament health.[25]

But aging doesn't just reduce our mobility - it also changes our appearance. As we get older, decreased collagen and a shift in the type of collagen we produce often lead to wrinkles, crow's feet, and other skin features that many people wish to minimize wherever possible and as fast as possible.

Fortunately for them, a 2019 study found that a collagen type II-rich extract (sourced from chicken sternums) improved the tone of facial epidermis in healthy adult women.[26]

-

Calm, Mood, & Stress Support

Most supplements like this simply opt for ashwagandha. Team Animal uses that, but thanks to the pak form factor, they've got room to add much more:

-

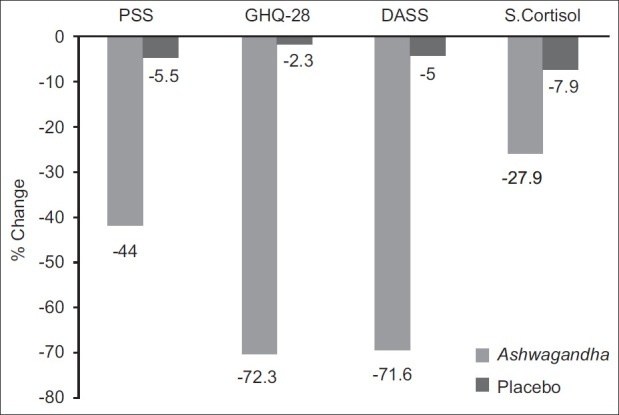

Ashwagandha Extract – 300 mg

Famed for its abilities as an adaptogen, a class of compounds that can normalize the human stress response (turning it up when too low, and turning it down when too high), ashwagandha has been used for millennia all over the world to treat a wide variety of health conditions.

With less stress and a healthier mentality, ashwagandha helps users stay even-keeled on track with goals

Recent research has borne this ancestral wisdom out, as scientists are finding more and more evidence that ashwagandha can help manage chronic stress, whether it's physical or mental.[27-30]

Ashwagandha works much of its magic by reducing our blood levels of cortisol,[27-30] the main human stress hormone, which leads to a corresponding decrease in anxiety, stress, and mood.

However, ashwagandha also has powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and even immunomodulatory properties.[27-30]

Since aging is associated with a rise in average daily cortisol levels,[31] keeping cortisol under control should definitely be a priority for anyone who is trying to age gracefully and slow typical sings of aging.

-

L-Theanine – 100 mg

Theanine is an amino acid that's found in high concentrations in tea leaves. In the brain, theanine behaves like a neurotransmitter[32] and has calming, anxiolytic effects – without sedation.[33-35]

According to the research literature, theanine does this by increasing our levels of three key neurotransmitters that are essential for optimal brain function: dopamine, serotonin, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA).[36-40]

If you're a habitual caffeine user (as most of us are), you'll be happy to hear that L-theanine shows synergistic effects with caffeine.[41] In the research literature, people who take caffeine and theanine together consistently show better reaction times, working memory, and alertness.[42,43]

Research indicates that theanine supplementation can significantly improve sleep quality.[40]

-

Gotu Kola Herb Powder – 100 mg

Much like theanine, gotu kola is known for its substantial anxiolytic properties. But it also stimulates neurogenesis, the process by which the brain — even the adult brain — generates new neurons and dendritic connections between neurons.[44-47]

-

Eleutherococcus senticosus Root Powder – 100 mg

Much like ashwagandha, Eleutherococcus senticosus, also known as Siberian ginseng, is an adaptogen with a powerful ability to normalize and balance the stress response.[48] It works its magic mostly by increasing the expression of neuropeptide Y, which helps reduce the symptoms of stress and anxiety.[49]

-

-

Bioavailability & Absorption

Not one, not two, but three ways to boost absorption -- and each one carries its own unique added benefits. We especially appreciate the adddition of ginger here:

-

AstraGin (Panax notoginseng & Astragalus membranaceus) – 25 mg

Ginseng is chock full of ginsenosides that have been shown to regulate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), an enzyme that catalyzes the the conversion of AMP to ATP, thus regulating overall cellular energy.[50,51]

The ATP-producing ginsenosides increase bioavailability of ingredients by improving nutrient absorption in the intestine: because the absorption of nutrients is an energy-intensive process,[52,53] increasing the ATP available to intestinal cells also increases the quantity of nutrients that those cells are able to transport across the intestinal wall and into the bloodstream.

AstraGin is a combination of Astragalus and Panax Notoginseng that's been shown to increase ingredient absorption

The astragalus half of this blend is rich in astragalosides, bioactive compounds that have been shown to improve heart health, increase collagen synthesis, improve metabolic function and neurological health, and improve the function of the liver.[54-61]

Astragalosides have similarly beneficial effects on intestinal function.[62]

When tested in a research setting, AstraGin has been found to significantly increase the bioavailability of amino acids, nutrients, water-soluble and fat-soluble vitamins.[63]

-

Black Pepper Extract (BioPerine) – 5 mg

Like AstraGin, BioPerine is famed for its ability to increase the bioavailability of supplements. It inhibits the stomach enzymes that break your supplements down before they can reach the intestinal wall, where they are absorbed into the bloodstream.[64]

But BioPerine has some other good effects – the piperine in BioPerine increases GLUT4 activity,[65] the transporter that moves glucose out of the bloodstream and into muscle tissue where it can be used for growth and repair.

BioPerine also has some activity against insulin resistance and fatty liver,[66] and is a powerful antioxidant.[67]

-

Ginger Root Powder – 250 mg

Ginger is well-known to help with nausea.[68-78] But even better, it has powerful anti-inflammatory properties[79-81] and has been shown to alleviate symptoms of osteoarthritis.[82,83]

Beyond that, there's even a study showing that high-dose ginger can prevent muscle pain 24-48 hours post workout![84]

Like BioPerine and AstraGin, ginger root powder helps increase the efficiency of digestion and nutrient absorption, by stimulating the release of gastric and pancreatic enzymes.[85] But as you can see above, it provides so much more than faster gastric emptying, and is a perfect way to end such a supplement.

-

Dosage and Directions

Take one pack (which has five capsules) once daily. Animal Alpha F will usually be best taken with food.

Takeaway: The women at Animal get what they've needed

Animal Alpha F is wellness and balance from the alpha female.

By optimizing the body's estrogen balance and supporting collagen and cartilage synthesis, Animal Alpha F paks from Universal Nutrition is a powerful tool in the arsenal of any female athlete.

This is an incredible stack that can be added to numerous Animal supplements, Animal Immune Pak, Animal Greens, and Animal Flex. It can also be combined with tried-and-true pre-workouts like Animal Fury and Animal Primal.

Universal Animal Alpha F – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)