Animal Pak users have been training for this very moment.

No, we're not talking about going for that squat PR, although they've been training for that too. We're talking about a largely-dosed joint health supplement.

One that includes the tried-and-true everyday "old school" ingredients like glucosamine, chondroitin, and MSM, along with some more "modern" anti-inflammatory ingredients like novel omega-3 fatty acids, boswellia, and quercetin.

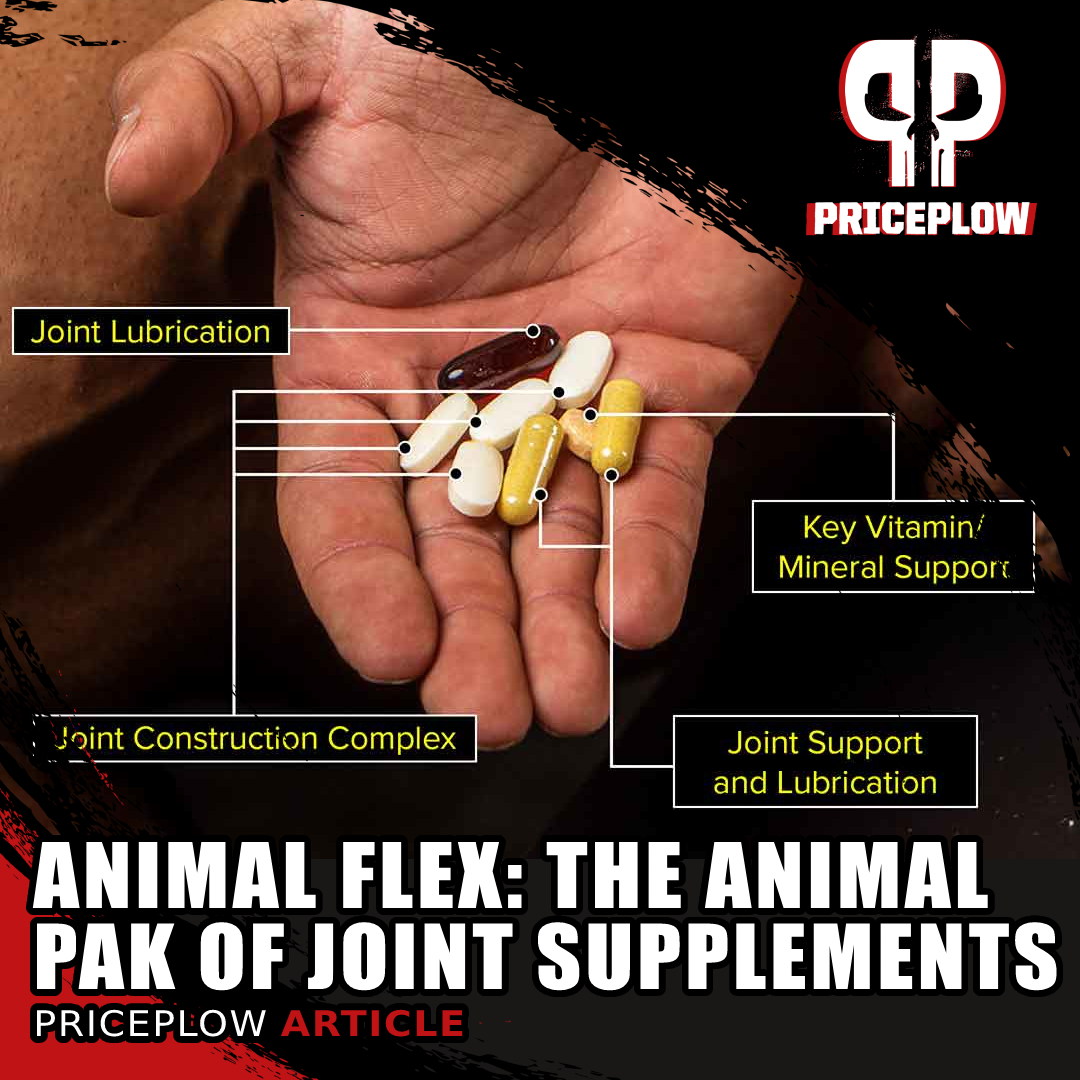

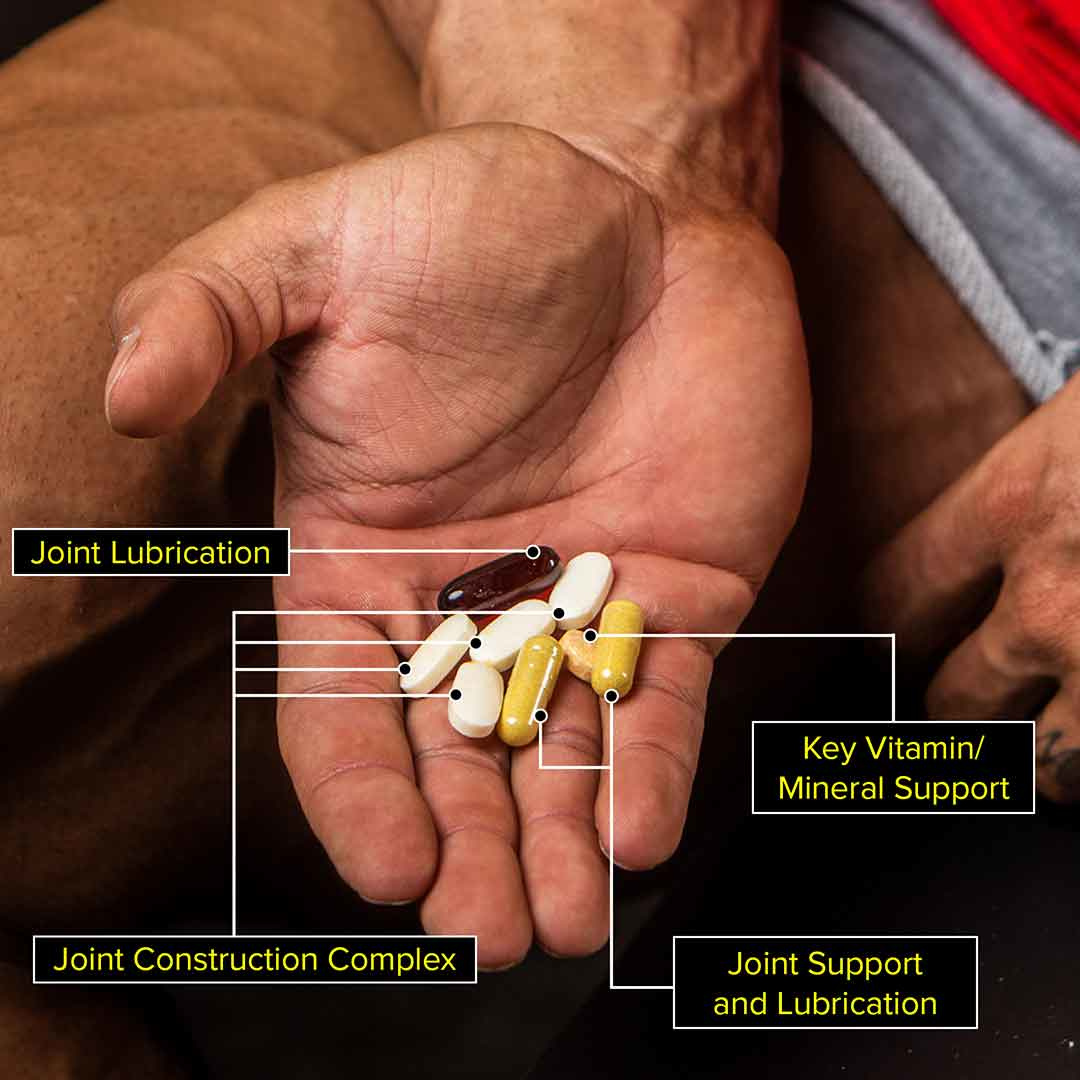

Meet "The Animal Pak of Joint Supplements": Animal Flex! And if this many pills isn't your style, take a look at the collagen-boosted Animal Flex Powder.

When most brands have to choose between large doses of glucosamine/chondroitin/MSM and other ingredients, Animal has a better solution:

Animal Flex: The "Why Don't We Do Both?" Supplement

With long enough use, glucosamine, MSM, and chondroitin have solid scientific backing. The only issue is, they alone take up 5-6 capsules, leaving little room for other ingredients!

But when your customers are already used to taking vitamin packs, you're at a solid advantage. That's exactly what Universal Nutrition did with Animal Flex, keeping efficacious amounts of glucosamine while also adding novel fatty acids and herbs. It's always been available in "Pak" form, but is also available in powder form, swapping out the omega-3s for collagen.

This year, make it your goal to keep your joints running strong so that you're running strong. We cover Animal Flex's ingredients below, just after showing our PricePlow-powered prices and video training:

Universal Animal Flex – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming Ingredients video.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Animal Flex Ingredients

Below, we'll focus on the Flex packs, but then talk about some of the differences in the powder as well.

-

Joint Construction Complex

Some ingredients simply require high doses, and glucosamine and MSM are two of them. This works out in the favor of packs or powders, because to get this combination alone in efficacious doses, we'd need five large capsules as it is.

With "ordinary" supplements, that's about all the capsules a brand would want to use. But for Animal Pak users, we're only getting started:

-

Glucosamine (as HCl, sulfate 2KCl)

One of the most important health ingredients on the market, glucosamine is a classic in joint supplements. However, as mentioned above, it requires high dosing (usually 1.5 grams per day), which makes it perfect for Animal Flex, whether it's in the pack or powder form.

Glucosamine is a compound that's naturally-found in joints and cartilage.[1] It defends against joint breakdown, and is used to keep the integrity of our critical soft tissue. It's been researched a lot, with the top forms being glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride[2] - Animal, of course, uses both.

There are two notes about glucosamine, however:

-

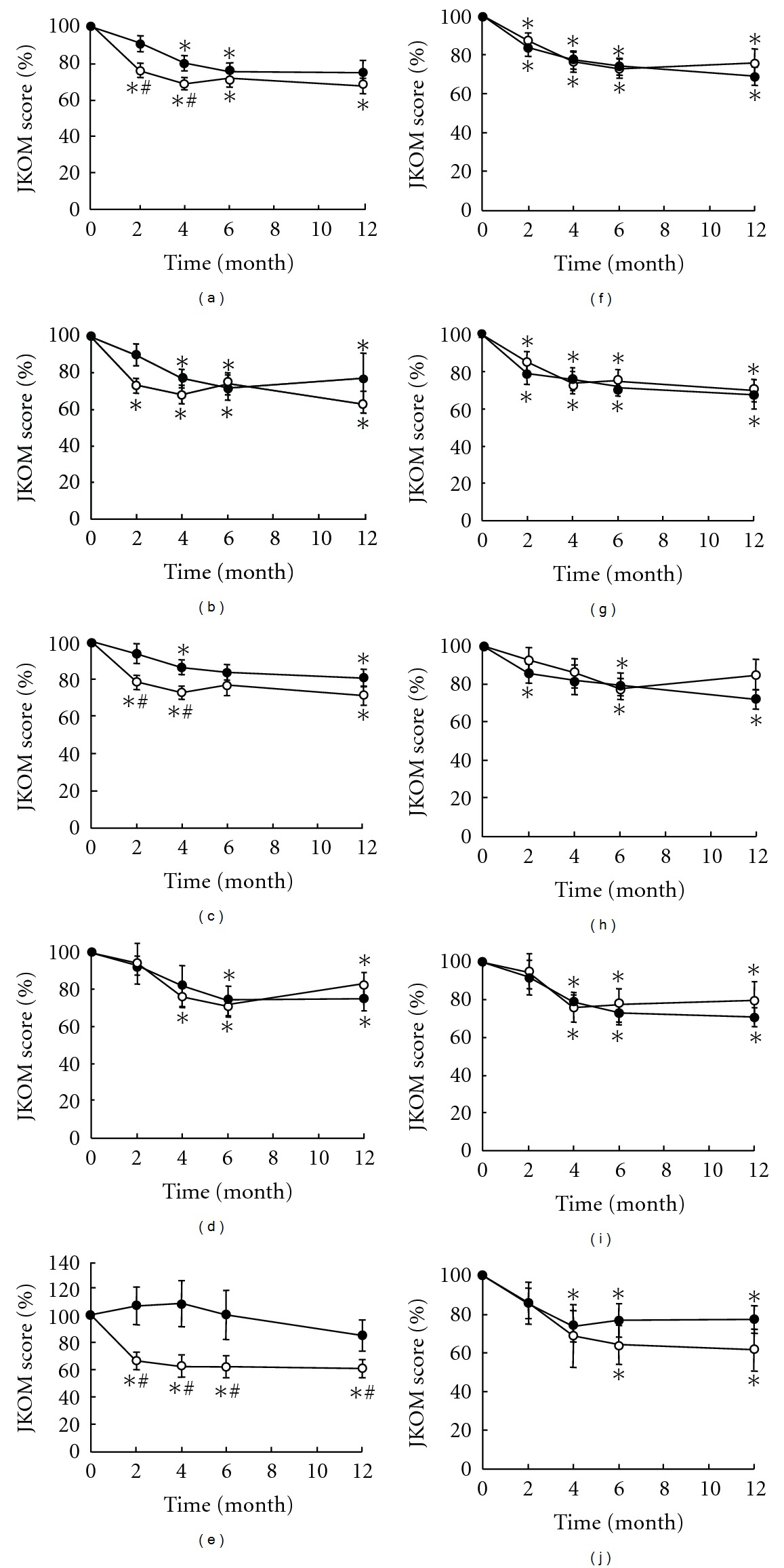

It requires time to work - up to six months of use

-

It requires high doses that most humans don't adhere to for a long period of time

Pain reduction, anti-inflammatory effects, and collagen protection

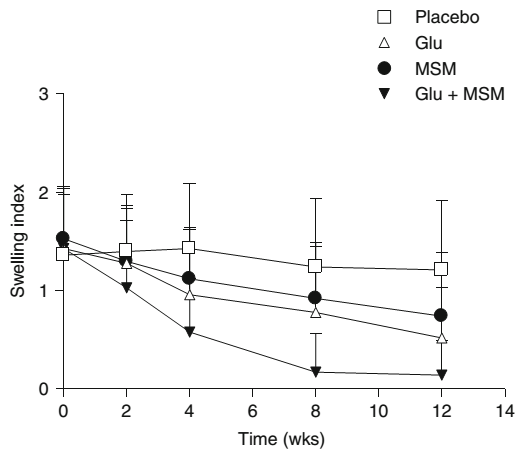

Both MSM and MSM+Glucosamine proved incredibly effective in reducing the swelling index in patients with osteoarthritis.[3]

With Animal's customers, we're not worried about these, and the payoff is that longer-term studies show great efficacy. For instance, in 2007, glucosamine was used on knee osteoarthritis for six months in comparison to acetaminophen (the pain reliever in Tylenol) and placebo. After six months, there were significantly fewer symptoms compared to placebo, and it even showed less pain than the acetaminophen group,[4] although not to a statistically significant difference.

Glucosamine has been shown to decrease high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) by 28% and PGE-M by 24%[5] - knocking down two major markers for inflammation.

In addition, there are studies showing that glucosamine usage led to a reduction of collagen degradation.[6,7] Note that one study was with 3 grams per day, which we won't have here, but the other is 1.5 grams per day, which we likely do!

A reduction in all-cause mortality

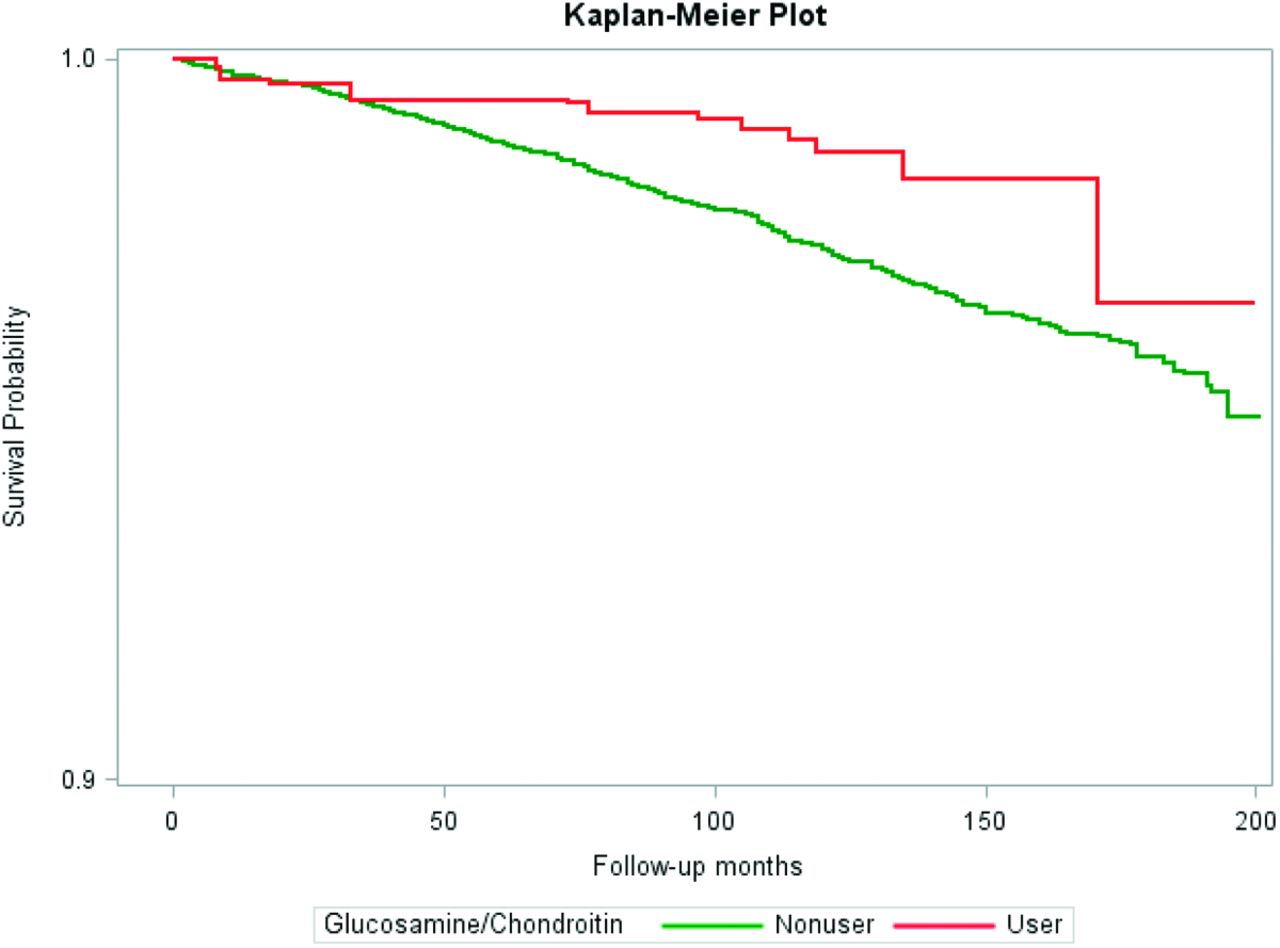

Finally, we must mention the ultimate longevity angle: a cohort study published in 2020 that had been looking at middle-aged men and women from 2006 to 2010, with a follow-up in 2018, noted that regular glucosamine users had a 15% reduction in all-cause mortality![8] Another study published later in 2020 confirmed findings, with a 39% reduction in all-cause mortality in glucosamine/chondroitin users.[9]

Interestingly, the reductions were shown in cardiovascular and respiratory diseases,[8,9] not just broken hips and falls. While we do note the healthy user bias (folks taking glucosamine will tend to be more healthy in general), there seems to be something more going on with the ingredient in terms of longevity. For instance, recent research showed that glucosamine functions as a senolytic, helping the body clear out dead cells in a way that's similar to fasting![10]

So there's more to glucosamine than just joint health.

Because of the large dose needed, modern and fancy joint health supplements often ignore it, and that's a mistake Animal users won't have.

-

-

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

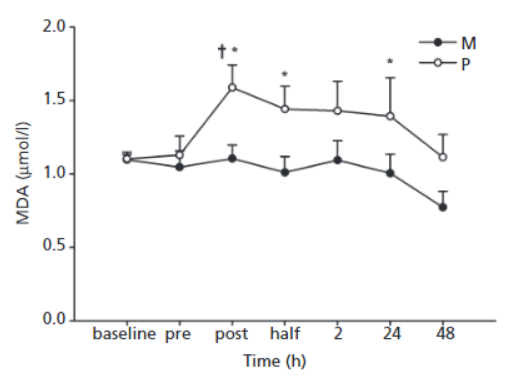

Figure 2 Effect of MSM on serum MDA (malondealdehyde, a marker of lipid peroxidation) levels in healthy young men

after an acute bout of exercise.[11]Often seen alongside glucosamine, and also often requiring a relatively large dosage is MSM, short for methylsulfonylmethane. This is an active sulfur donor, and sulfur is a mineral that's a key player for connective tissue maintenance.

A randomized controlled trial published in 2004 showed that MSM has a comparative effect to glucosamine in terms of pain and swelling, but the best effects were seen when combining them both together![3] MSM also performed admirably for knee pain and overall function in a study published in 2011.[12]

In addition, MSM has been shown to provide a unique reduction of muscle damage after just ten days of supplementation,[11,13] functioning as an antioxidant that most athletes don't consider. We generally see a gram as the clinical dose, and we're likely right around that here in Animal Flex.

-

Chondroitin Sulfate (A and C)

Animal Flex contains two types of chondroitin sulfate, which is often paired with glucosamine in research. Chondroitin is a major part of the extracellular matrix found in our ligaments, tendons, cartilage, skin, and bone.[14] It helps with elasticity and resistance in our cartilage, helping the body withstand more pressure and loading at different angles - perfect for Animal athletes!

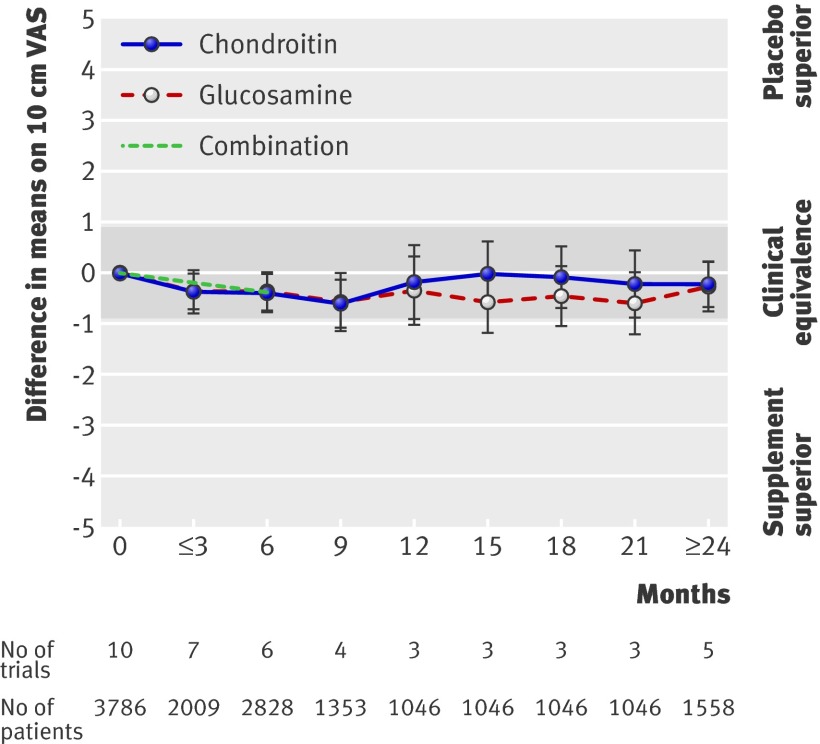

Note here that negative values mean benefits over placebo! Using glucosamine and chondroitin lowered pain intensity![83]

A review of research on chondroitin found that it lower levels are found in people with osteoarthritis, and supplementing it may help improve repair.[14] Additionally, numerous studies have shown it to be an anti-inflammatory, anti-catabolic antioxidant that may even have anabolic properties![14] Multiple studies have also shown that chondroitin can increase type II collagen production.[15,16]

Chondroitin normally plays second fiddle to glucosamine, and that's fine - since we have both of them here, we can show the research showing that both of them help delay knee osteoarthritis.[17] A 2018 meta-analysis on 30 trials showed that they alleviate pain symptoms and improve function while reducing stiffness.[18]

-

-

Joint Lubrication Complex

-

Flaxseed Oil (50% alpha linolenic acid)

Flaxseed oil is rich in alpha linolenic acid (ALA - not to be confused with alpha lipoic acid), which is an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid. In general, higher omega-3 levels (compared to omega-6) are associated with less inflammation and pain found in numerous conditions including arthritis.[19-22]

With EPA and DHA getting all of the attention in omega-3 supplements, ALA is often overlooked.[23] It is actually the precursor to EPA and DHA (as well as DPA), all of which help with brain development and function, cardiovascular health, and inflammatory response.[24,25]

Higher levels of ALA in the blood have been associated with reduced markers of inflammation.[26] ALA seems to elicit its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1beta, and TNF-alpha, as shown in a study where a high-ALA diet improved these markers.[27]

This oil is a perfect fit in the "Joint Lubrication Complex". Below we get even more support:

-

Cetyl Myristoleate Proprietary Blend

Animal included a unique blend Cetyl Myristoleate Blend containing the following:

- Cetyl Myristoleate

- Cetyl Myristate

- Cetyl Palmitate

- Cetyl Laurate

- Cetyl Palmitoleate

- Cetyl Oleate

These types of blends are additional fatty acids often used to treat joint pain.[28] Research suggests that they can reduce joint pain, decrease joint inflammation, and prevent additive joint damage.

The primary mechanism seems to be through the inhibition of a couple of arachidonic acid pathways. Arachidonic acid is an inflammatory fatty acid that, while anabolic, can lead to excessive inflammation when too much omega-6 is consumed. The ingredients in the cetyl blend express anti-inflammatory, pain-mediating effects through this inhibition, while also stabilizing cell membranes and protecting against oxidative stress.[28]

A double-blinded placebo-controlled study published in 2017 tested cetylmyristoleate on 28 people with mildly arthritic knee pain, and determined that it was effective at all concentrations for reducing knee pain after 12 weeks and a 4-week follow-up.[28]

-

Hyaluronic Acid

"The results of the present study have shown that the oral administration of HA may have beneficial therapeutic effects on patients with symptomatic knee OA and may be even more beneficial for relatively young patients"[31]

Hyaluronic acid has become popular in skin care supplements, but Animal first had it in their Animal Flex joint care packs. Alongside collagen, hyaluronic acid (HA) is found in the extracellular matrix, and it has a unique molecular structure that allows it to attract and retain water throughout the body.

Beyond joints and skin, hyaluronic acid is found nearly everywhere, such as in the eyes, muscle tissue, heart, lungs. But our focus is generally how it leads to better joint health through a method of lubrication in the soft tissues like skin, where HA can help with water balance and osmotic pressure.[29]

When dosed high enough, hyaluronic acid has some studies relevant to sports nutrition and joint pain reduction.[30,31] It has been shown to reduce knee joint pain when used long-term, and one of those studies was only at 80 milligrams per day.[30]

With the relatively low doses needed, we're surprised we don't see HA used more often in joint supplements. Team Animal doesn't miss with this Joint Lubrication Complex though.

-

-

Joint Support Complex

-

Ginger Root (gingerols, shogaols)

Most people are familiar with ginger's effects on nausea, but don't forget that it has incredible anti-inflammatory properties as well![32-34] A couple of studies have shown ginger to help successfully fight osteoarthritis as well,[34,35] synergizing with other ingredients here.

Muscle pain reduction!

Animal Flex isn't just about joint flexion though! On top of MSM's reduction in muscle damage, ginger has been shown to reduce muscle pain 24 and 48 hours post-workout![36] This was confirmed with a meta-analysis on 7 total studies, demonstrating muscle pain reduction after about five days of use.[37]

If it's not joint pain getting to you Animals, it's muscle pain -- so don't overlook ginger!

-

Turmeric Root (curcumin)

"A curry a day keeps the joint pain away!" A while back, we wrote about curcumin for joint pain, but there's so much more this compound can do!

Curcumin is the active pigment that's part of turmeric root,[38] and has long been used for numerous applications, including general anti-inflammatory health and wellness.[39-41] By inhibiting the COX-2 enzyme[41-43] (similar to NSAID drugs) alongside other mechanisms of action, curcumin reduces oxidative stress[38,44-49] and overall inflammation.[50-55]

All in all, curcumin has been consistently shown to reduce pain[48,50,56-67] and improve osteoarthritis symptoms,[48,50,56,57,60-63,67] right in line with what Animal Flex users would like.

The research is deep on this one, and there are also cardiovascular benefits, unlike some of the other NSAIDs that can cause cardiovascular problems.[68]

-

Boswellia Serrata Extract (gum) (Boswellic Acid)

Also known as Frankincense, boswellia serrata has a potent gum resin that has historically been used for various inflammation-driven conditions. It has been shown to help combat osteoarthritis symptoms by reducing inflammation.[69,70]

Boswellia works by lowering the levels of 5-lipoxygenase, a known inflammatory enzyme.[71] In addition, it can inhibit leukotriene production,[70,72] reducing the output of these inflammatory molecules that the body releases in response to conditions such as allergy and asthma attacks. FInally, thanks to its unique and powerful acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA) component, boswellia also reduces NF-kappa B,[73] which is a factor in many high-inflammatory conditions including arthritis.[74]

These mechanisms are why it should be included in more joint supplements - it works, works broadly, and works differently than many other ingredients.

-

Quercetin

Quercetin has received a lot of coverage for its immune-supporting properties as a zinc ionophore, which we recently covered in our Animal Immune article. However, it also sports many anti-inflammatory properties.[75,76]

We've seen high-dose quercetin usage lead to a decrease in exercise-induced stress,[77] and while we don't have that large of a dose here, it could be a reason why it's been added.

-

Bromelain

An anti-inflammatory compound often paired with quercetin in anti-allergy supplements,[78] bromelain is a unique enzyme that's found in pineapple and helps with protein digestion (which is why it's great to cook meat with the fruit).

Universal Animal Immune Pak comes in both paks (pills) and powder, and has many of the ingredients we preach for modern immune concerns!

However, bromelain is here for its anti-inflammatory properties -- it can reduce knee pain![79] All the better if it helps you digest your protein as well.

-

-

Added vitamins and minerals

To support collagen synthesis and more, Animal Flex packs also have the following added:

- Vitamin C

- Vitamin E

- Zinc

- Selenium

- Manganese

What else is in the Animal Flex powder?

Beyond the above blend, Animal Flex Powder also has collagen added, making the Joint Lubrication and Support Complex into one large 6 grams blend. Atop its cardiovascular benefits,[80] collagen supplementation has been shown to improve connective tissue and joint health as well.[81,82]

This replaces the ALA (alpha linolenic acid) from flaxseed oil, so instead of 1 gram of fat on the label, you end up with 4 grams of protein. Not that we're here for the macros, but it's important to understand the differences between the packs and powder.

All Animal Flex Flavors / Variations Available

The "Animal Pak" of Joint Supplements

Animal isn't just about Animal Pak. When it comes to creating a proper joint supplement, brands often make concessions for or against glucosamine, MSM, and chondroitin due to the amount of space they take up. They either underdose it, or ignore them altogether in favor of other popular anti-inflammatory ingredients like curcumin and boswellia.

But there are definite benefits when your customer is used to taking nine pills at a time in a single pack. Animal Pak has trained Universal Nutrition's consumers for this very moment: a joint supplement formula that takes the "why don't we do both?" approach!

So if you're not afraid of throwing down a pack of pills to get the joint support you need, then Animal Flex should definitely get consideration. And if you're not into that, then there's still powder as well - with collagen to boot.

Universal Animal Flex – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)