AstroFlav is a company known for its astronomically great flavors. But in recent years, they've stepped up their capsule-based supplement game too, and, following a familiar industry arc, have branched out from traditional bodybuilding and sports nutrition supplements into health and wellness products.

And when it comes to long-term health, there's perhaps nothing more important than maintaining insulin sensitivity and keeping blood glucose to an appropriate minimum. Of course, we don't want to go too low – but in the modern world, the battle is much more about keeping blood sugars from rising over time.

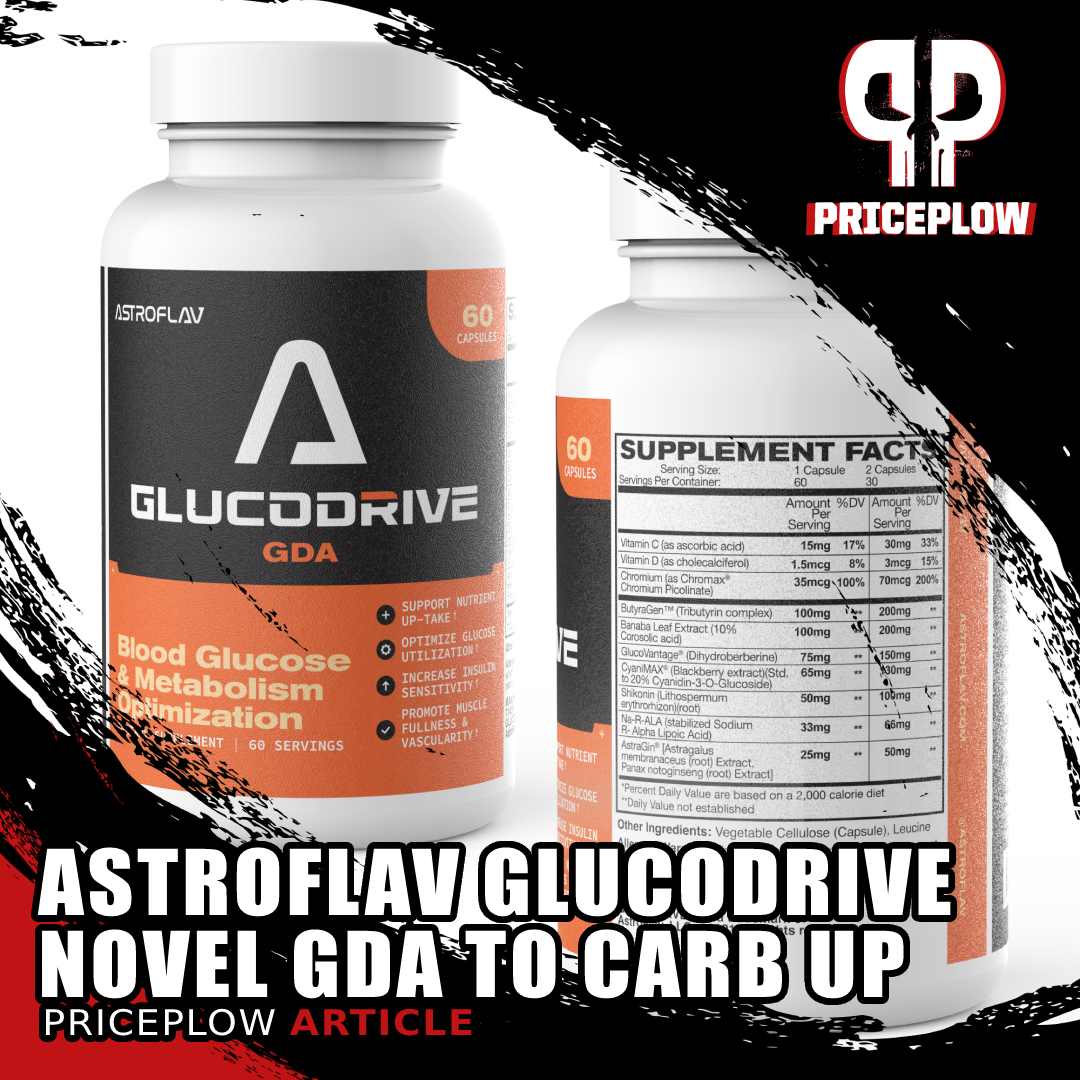

AstroFlav GlucoDrive is a glucose disposal agent (GDA) with some tried-and-true ingredients like GlucoVantage dihydroberberine combined with a couple new ingredients like CyaniMAX to drive improved insulin sensitivity!

It matters a lot, since fasting glucose is positively correlated with morbidity and premature aging.[1]

AstroFlav GlucoDrive launches in time for the 2024 New Year

So, in order to help your body process glucose as efficiently as possible, AstroFlav has given us GlucoDrive – a glucose disposal agent (GDA) formula.

This is a category of dietary supplement that helps you take better advantage of your carbohydrates. By taking it before a carb-containing meal, you can increase insulin sensitivity, directing more blood sugar to the muscle tissue (especially if you've been training hard), as opposed to liver or fat storage. And GlucoDrive has some novel ingredients inside:

New ingredients combined with some GDA favorites

GlucoDrive starts with a unique tributyrin complex combined with NNB Nutrition's GlucoVantage dihydroberberine, and has some novel ingredients like shikonin and CyaniMAX making for quite a groundbreaking formula. This is no surprise, if you've seen our article on A-Pump, one of the most novel nitric oxide supplements we've ever seen.

Let's get into how it works, but first check PricePlow's AstroFlav's news and deals:

AstroFlav GlucoDrive – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

GlucoDrive Ingredients

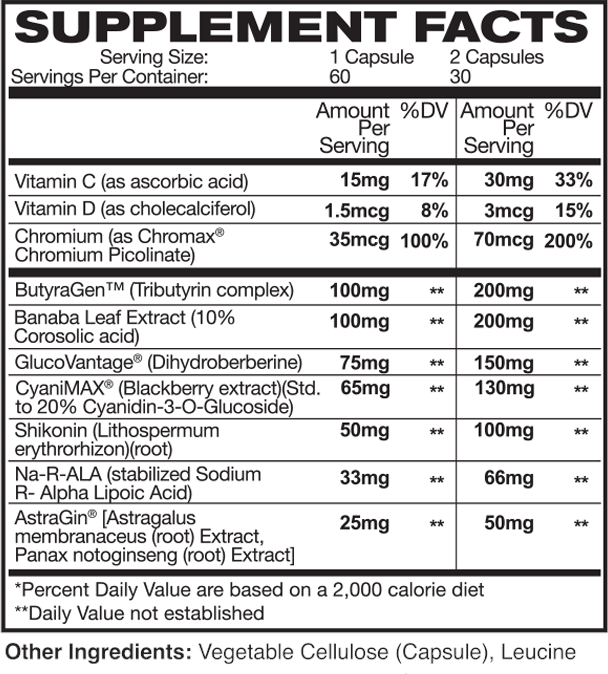

In a single 2-capsule serving of GlucoDrive from AstroFlav, you get the following:

-

ButyraGen (Tributyrin complex) – 200 mg

You've heard about probiotics, and prebiotics – but have you heard about postbiotics? That's the category that tributyrin falls into.

Whereas prebiotics act as food for beneficial microorganisms,[2] and probiotics consist of those microorganisms themselves,[3] postbiotics are derived from probiotic organisms. There are several kinds of postbiotics, but what we have with tributyrin is a bioactive metabolite that's created when probiotic bacteria ferment fiber.[4]

In other words, supplementing with tributyrin can give you some of the metabolic benefits associated with increased fiber intake.

More specifically, tributyrin is a precursor to butyric acid, also known as butyrate, which is produced when symbiotic microorganisms break down fiber.[5] Butyric acid/butyrate is the preferred energy source for many cells within the gastrointestinal tract, and increased butyrate synthesis via fiber intake is linked to positive effects on immune function, body weight regulation, caloric balance, and even cognitive performance.[5]

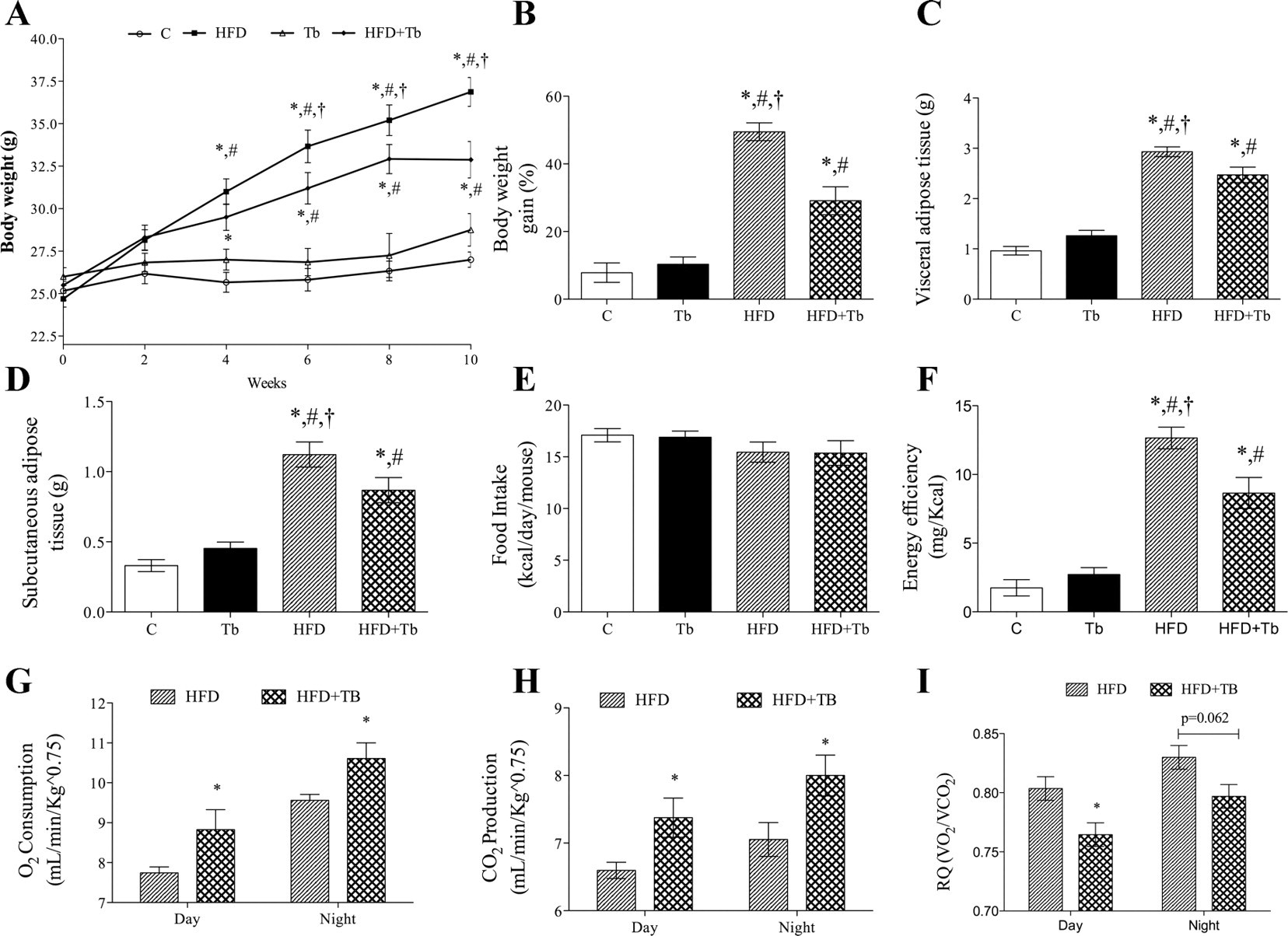

Long-term studies have found a positive correlation between the presence of butyrate-producing bacteria and insulin sensitivity.[6] Targeted butyrate supplementation has also been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and prevent the onset of fatty liver, a key component of the metabolic syndrome.[7]

As is often the case, the precursor (tributyrin) is more orally bioavailable than the target molecule (butyrate),[9] which is why we prefer supplementing with tributyrin instead of butyric acid itself.[9]

Tributyrin supplementation can help with:[4,5]

- Boosting the immune system

- Fighting inflammation, tackling various GI issues

- Enhancing gene expression in digestive, gut, and GI systems

- Improving communication among beneficial microbes

- Balancing microflora ratios (favoring good over harmful bacteria)

- Providing antioxidant effects and reducing oxidative stress

- Enhancing regular bowel movements and alleviating constipation

The only real downside to tributyrin supplementation is that it doesn't smell very good, but since GlucoDrive is a capsule-based supplement, that shouldn't be much of a problem.

-

Banaba Leaf Extract (10% Corosolic acid) – 200 mg

Banaba, indigenous to Southeast Asia, boasts a rich history of traditional use, first documented in scientific literature circa 1940.[10] Renowned for its anti-diabetic, antioxidant, anti-obesity, and antilipidemic properties, scientific interest in the nutraceutical potential of this tree has only grown since then.

The key bioactive constituent within banaba is corosolic acid, recognized for its potent anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial characteristics.[10] Studies involving induced diabetes in rats, supplemented with pure corosolic acid, have demonstrated the acid's ability to mitigate the inflammation and hypertension associated with obesity.[11]

Corosolic acid acts by inhibiting gluconeogenesis, reducing triglyceride and cholesterol levels, and preventing steatosis—the accumulation of liver fat leading to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).[12]

But banaba has a diverse range of bioactive constituents, including ellagitannins, oleanolic acid, and valoneic acid, which all contribute to its anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects.[10]

Research highlights the efficacy of banaba leaf supplementation in fostering cellular glucose uptake, enhancing glycemic control, boosting insulin sensitivity, and hindering glucose absorption by impeding the digestive breakdown of sucrose.[10]

-

GlucoVantage (Dihydroberberine) – 150 mg

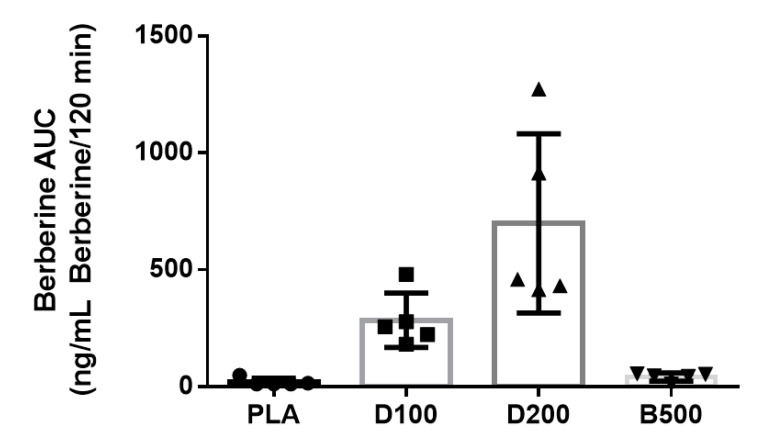

We've extensively covered GlucoVantage in the past, including a dedicated special topic article for this safe and effective[13] glucose disposal agent. While 150 milligrams may seem like a small dose, it's not. GlucoVantage is incredibly potent, with a remarkably high oral bioavailability compared to that of regular berberine.

We've long said that GlucoVantage dihydroberberine has 5x the bioavailability if traditional berberine. In our '5X' article, we explore the very well-designed study that demonstrated this.

In order to understand why, let's run through a quick summary of how berberine is metabolized by the body. First, berberine undergoes conversion by the gut into a metabolite known as dihydroberberine, which is essentially a hydrogenated (i.e., with hydrogen atoms added) form of berberine. Upon transitioning from the gut to the intestine, dihydroberberine is absorbed through the intestinal wall, where it is converted back into berberine and enters the bloodstream to exert its biologically active effects.

NNB Nutrition, the maker of GlucoVantage, discovered that direct administration of dihydroberberine can elevate blood berberine levels more efficiently by circumventing the bottleneck of berberine-to-dihydroberberine conversion in the gut.[13]

The efficiency boost is substantial—when tested in a laboratory setting, GlucoVantage demonstrated five times greater bioavailability than regular berberine.[13] Moreover, the effects of dihydroberberine supplementation are more enduring than those of regular berberine.[14,15]

Beyond enhanced efficacy, supplementing with GlucoVantage offers additional benefits. Given the poor bioavailability of ordinary berberine in some individuals, particularly those with compromised gut health, achieving clinical efficacy may necessitate large doses—up to 1.5 grams or 1,500 milligrams.[16] Unfortunately, such large doses come with the risk of gastrointestinal disturbances.[17,18] Opting for GlucoVantage over regular berberine allows us to achieve the same effects with a much smaller dose, thus mitigating these issues.

A study published in early 2022 showed that NNB Nutrition's GlucoVantage dihydroberberine outperformed higher doses of normal berberine in elevating plasma berberine and reducing blood sugar and insulin levels![19]

With GlucoVantage, you receive all the customary advantages of berberine supplementation, including improved glucose uptake—especially beneficial for diabetics—enhanced insulin sensitivity, lower insulin levels, improved glucose uptake in muscle cells, and a healthier body composition.[17,20-23] All these benefits come in a more potent, efficient, and compact dose.

There's even more, including a new pilot study showing how GlucoVantage dihydroberberine beat berberine in humans,[19] a trial covered extensively on our blog that you can check into later. But moving on, we have another novel ingredient:

-

CyaniMAX (Blackberry extract)(Std. to 20% Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside) – 130 mg

Cyanidin-3-O-Glucoside is an anthocyanin polyphenol antioxidant that occurs naturally at high concentrations in strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries,[24] with the latter being the source of the CyaniMAX extract.

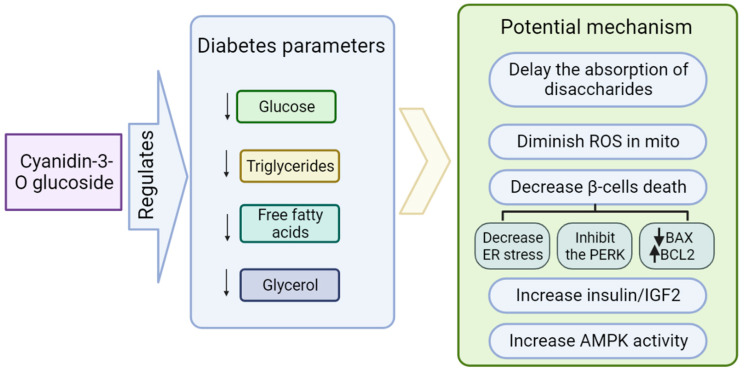

While human data on this ingredient remains sparse, compelling in vivo and in vitro research has demonstrated its potential to decrease serum glucose,[25] triglycerides,[26] free fatty acids,[27] and glycerol,[28] all of which can have a positive effect on the body's ability to properly metabolize glucose.[24]

The mechanisms of action behind glucoside's benefits – and those of anthocyanins in general – seem to be protecting mitochondria from oxidative stress,[29] preserving the health and function of your body's all-important pancreatic beta cells,[30] and upregulating AMPK.[31]

-

Shikonin (Lithospermum erythrorhizon)(root) – 100 mg

Shikonin facilitates the transportation of glucose into muscle cells by directly elevating calcium concentrations in skeletal muscle tissue, mirroring the effects of muscle contraction.[32]

Here's a direct quote from a study on the subject:[32]

"Contraction of skeletal muscles (such as that occurring during exercise) also leads to increased glucose uptake. This is in part due to AMPK-activation but also on non-AMPK mediated mechanisms which may include ROS and NO production, and importantly increases in intracellular Ca2+ levels. Furthermore, increased calcium levels can induce glucose uptake also independently of contraction and calcium ionophores are shown to increase glucose uptake in in L6 skeletal muscle cells as well as in primary skeletal muscle myoblast cultures."[32]

This mechanism establishes an "anabolic window", allowing muscles to efficiently absorb excess glucose, promoting improved glycogen storage and reduced fat storage.[33,34]

Remarkably, this process operates independently of insulin,[33] which to our knowledge makes shikonin unique among other glucose disposal agents (GDAs). That's a huge potential advantage, since overstimulation of insulin secretion can actually damage the pancreas over time,[35] so we do want to minimize it wherever possible.

Definitely a unique ingredient we haven't seen in a GDA before -- at least not in the sports nutrition industry.

-

Na-R-ALA (stabilized Sodium R- Alpha Lipoic Acid) – 66 mg

Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) is a fatty acid present in mitochondria, where it plays a crucial role in regulating cellular energy production.[36]

Our bodies are used to naturally using the R form. In supplements, it's more expensive... but it also works better.

In addition to increasing AMPK expression, as discussed with other ingredients, ALA also exhibits appetite-suppressing properties and aids the liver in metabolizing fat.[37]

A significant benefit of ALA is its ability to reduce fatty tissue in the liver, which is vitally important given the close association between fatty liver (specifically, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD) and conditions like insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Some researchers even posit that NAFLD may be a causative factor for diabetes.[38]

These effects add up to a decrease in blood glucose levels and an increase in insulin sensitivity.[38] Similar to the most effective anti-diabetic supplements, ALA has the potential to safeguard pancreatic beta cells—the cells responsible for insulin production and secretion—from destruction.[39]

ALA's ability to improve glycemic control is so impressive that it's actually being considered as a potential treatment for the diabetic neuropathy associated with chronic hyperglycemia.[40] Research indicates that ALA supplementation can not only lower blood glucose levels but also impact the crucial HbA1c marker.[41]

-

Chromium (as Chromax Chromium Picolinate) – 70 mcg (200% DV)

For over 25 years, Chromax chromium picolinate has been improving insulin sensitivity. We argue that it's only gotten better, as dietary deficiencies have gotten worse over this time period.

Chromax is Nutrition21's chromium picolinate ingredient. We like seeing this form of chromium used, as peer-reviewed research consistently demonstrates that it's the most effective and bioavailable form of chromium.[42,43]

Chromium works by amplifying the action of insulin, thus facilitating more efficient cellular transport of glucose.[44-46] In essence, chromium can improve insulin sensitivity, a crucial and arguably most important aspect of long-term metabolic health.[47]

While we're big fans of chromium supplementation, most actual health claims begin at the 200 microgram level. To learn about them, you can read our article titled "Chromium Picolinate: The Ultimate Trace Mineral For Insulin Sensitivity".

-

AstraGin [Astragalus membranaceus (root) Extract, Panax notoginseng (root) Extract] – 50 mg

AstraGin, a patented ingredient designed to optimize the bioavailability of food and supplements, operates by promoting the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in intestinal cells.[48-52] These cells require sufficient ATP to efficiently absorb nutrients from the digestive tract, and AstraGin enhances this absorption process by providing them with more ATP.

The inclusion of AstraGin in premium formulas like AstroFlav GlucoDrive, rich with designer trademarked and patented ingredients, is a logical choice. It ensures that you derive maximum value from every dollar spent on GlucoDrive.

Regular use of AstraGin may lead to improvements in intestinal health over time.[53]

-

Other ingredients

AstroFlav GlucoDrive also has some nice vitamin support. While we wouldn't consider these to be clinical doses, vitamin C and vitamin D both play important roles in facilitating the insulin response,[54,55] so every little bit helps.

-

Vitamin C (as ascorbic acid) – 30 mg (33% DV)

-

Vitamin D (as cholecalciferol) – 3 mcg (15% DV)

-

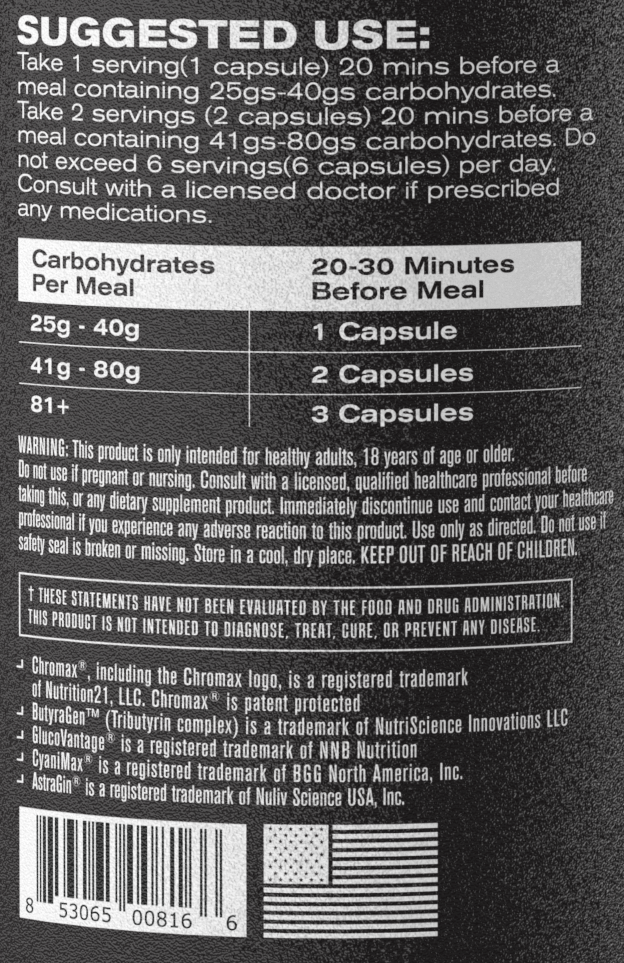

Dosage and Directions

AstroFlav provides a solid dosing chart on the side of the label, as shown to the right. The number of capsules depends on how many carbohydrates you're planning on eating in the following meal:

- 25-40g carbs: 1 capsule

- 41-80g carbs: 2 capsules

- Over 80 carbs: 3 capsules

Conclusion: Tried and True Meets Novel

This is a really cool formula overall, but GlucoVantage and corosolic acid are the real heavy hitters here. We're also particularly intrigued by CyaniMAX, as cyanidin-3-O-glucoside seems to be a promising if underutilized ingredient.

If you've tried a few GDAs in your day, and are looking for something that mixes ingredients we've seen work in human trials (GlucoVantage and Chromax, for instance), as well as some novel ingredients to bring something new to the table, then AstroFlav GlucoDrive is definitely one to try this year.

AstroFlav GlucoDrive – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)