Lifetime natural bodybuilder Doug Miller hasn't just killed it in physique competition – he's been killing it at Core Nutritionals too, where he's been President and CEO since 2005.

Core has a reputation for not messing around. The company stays abreast of industry and research trends, so any Core label will be made up mostly of ingredients with solid evidence and consensus behind them. And of course, the Core team makes damn sure that all the doses are solid too.

However, Core isn't just another cookie-cutter formulation house – their labels always have one or two ingredients whose inclusion reveals the company's subtle and sophisticated understanding of the science.

One famous example of this forceful-yet-nuanced approach is Core Fury, the company's foundational pre-workout that the PricePlow blog covered back in 2022, which contains pregnenolone, a precursor to all steroid hormones (including testosterone). Pregnenolone is an absolutely awesome ingredient, but still relatively obscure, and Core has been an industry pioneer in its use. Plus, Fury uses a 2,000 mg dose of taurine per serving, at a time when the vast majority of formulators are stuck on the arbitrary 1,000 mg standard.

And again, when the Core gang released Pump, their non-stim preworkout that we also covered in 2022, they didn't just go heavy on NO-boosting ingredients as is the industry custom – they also included PeakO2, an ergogenic blend that's a really smart but unusual choice for this product category.

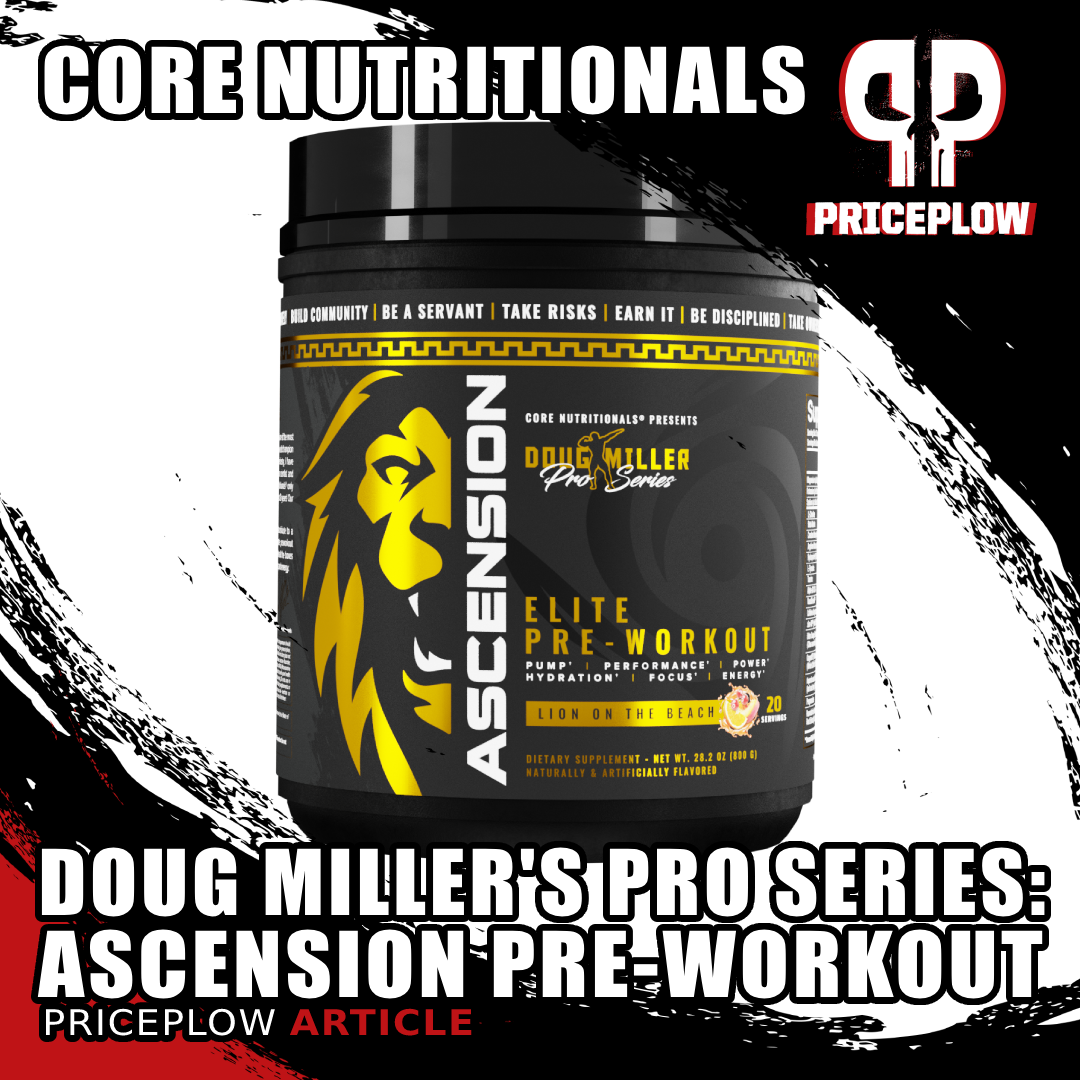

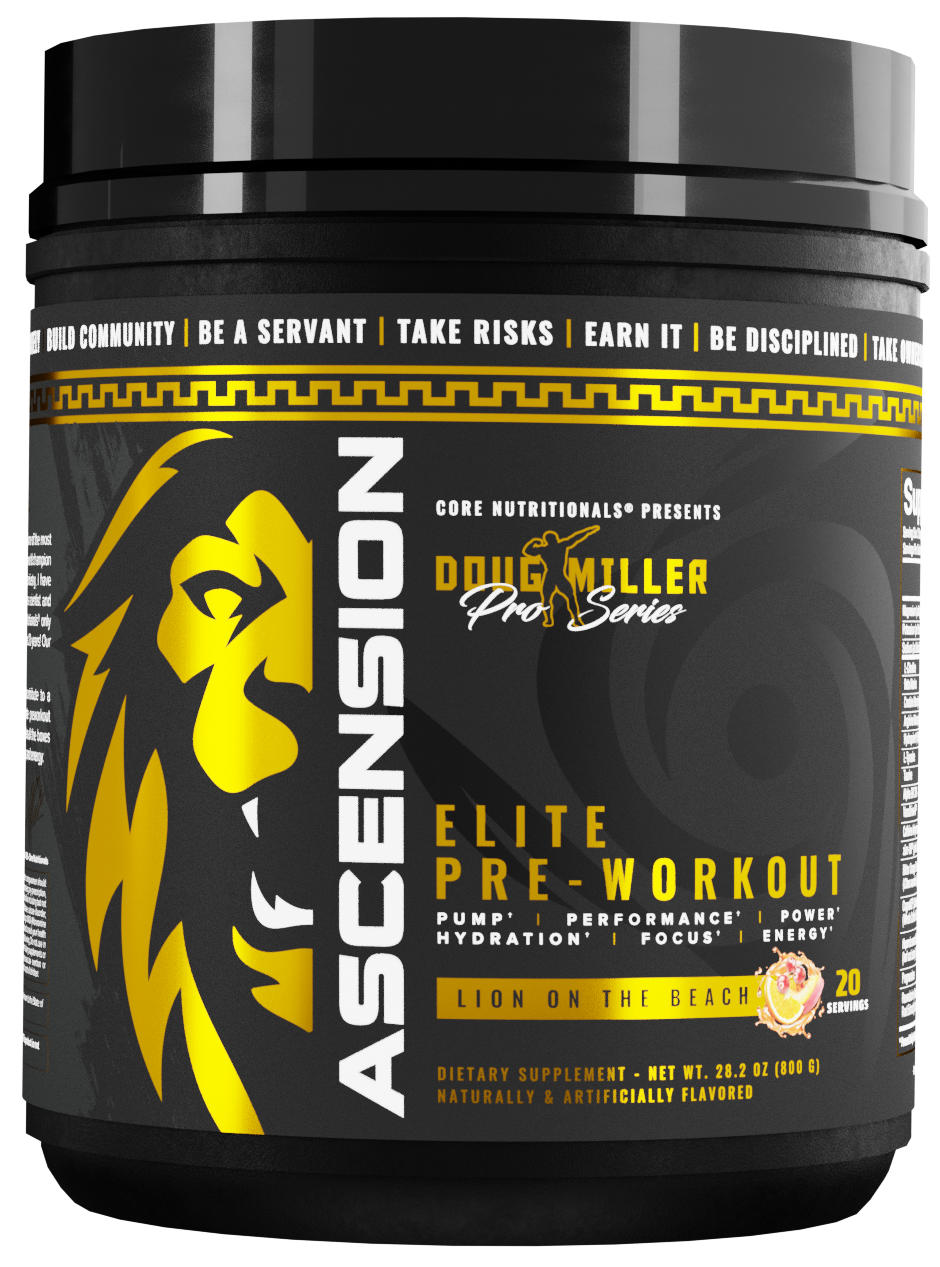

Core Ascension - Are You Ready to Ascend?!

Some key points to consider – in the two scoop serving you're getting 10,000 mg of citrulline, 6,400 mg of beta alanine, and 2,000 mg of taurine. All three of these doses have solid evidentiary support, and are gradually being accepted as the new industry standards, so it's increasingly common to see at least one of these show up in any given formula. Rarely, though, do we see all three of them at once.

Plus, Ascension uses pregnenolone, which, again, we're huge fans of.

Core Nutritionals Ascension – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Ingredients

In a single 2-scoop (40 gram) serving of Core Nutritionals' Ascension Pre-Workout, you get the following:

-

L-Citrulline – 10,000 mg

Citrulline supplementation can increase your body's production of nitric oxide (NO).[1]

Citrulline is a conditionally essential amino acid, which means your body can make some, but not all, the citrulline that it needs to cover your metabolic requirements. In order to achieve optimal citrulline function, supplementation is usually necessary, and this is particularly true during periods of acute stress, like injury or illness.

Although taking citrulline does increase NO production, citrulline is actually not the direct precursor to the molecule. Here's what the full NO synthesis pathway looks like, starting with citrulline:

Citrulline → Arginine → NO

You're probably wondering, 'Why not take arginine instead?' The answer is that arginine's oral bioavailability is too low for it to be an effective supplement. Citrulline's bioavailability is much better, so we take it instead.[2,3]

Why more NO?

Upregulating NO triggers vasodilation, a phenomenon where your blood vessels grow in diameter. This allows for a greater throughput of blood, which creates the much vaunted pump that bodybuilders and powerlifters are always chasing. Since you're then moving the same volume of blood through a bigger cavity, vasodilation causes blood pressure and heart rate to significantly decrease.[4-6]

Besides the obvious potential health benefits, vasodilation also improves the delivery of nutrients to, and the removal of metabolic waste from, all your body's cells.

Studies on citrulline have demonstrated that this supplement can:

- Improve power by increasing oxygen uptake[7]

- Extend athletic endurance by about 50%[8]

- Decrease post-exercise muscle soreness[8]

- Increase exercise-induced growth hormone (GH) secretion[9]

- Decrease protein catabolism[10]

- Amplify the anabolic response to exercise[11,12]

Citrulline can also help your body make more ornithine,[13] another amino acid that plays a crucial part in detoxifying your body of a metabolic waste product called ammonia.[14] We want to keep ammonia levels low, because when it accumulates, fatigue (both mental and physical) is the result. On the other hand, by speeding up the elimination of ammonia, the onset of athletic fatigue is thereby delayed.

Ornithine may help improve sleep quality by increasing the body's ratio of DHEA to cortisol.[14]

-

Beta-Alanine – 6,400 mg

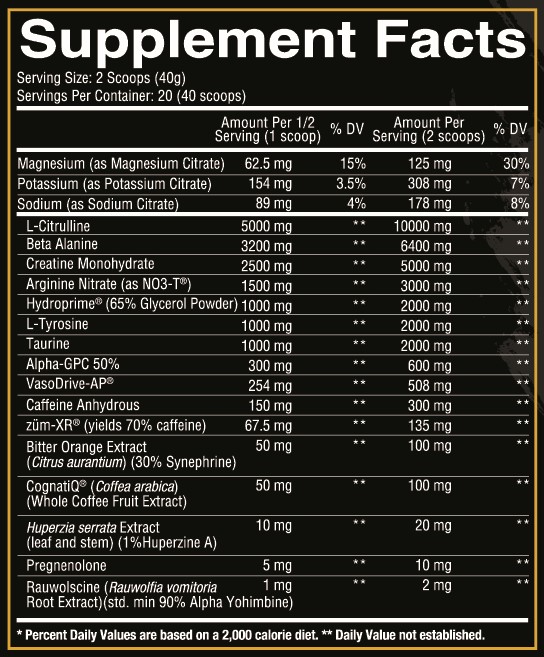

We're interested in section (B) here, where beta alanine alone shows great results compared to placebo.

Beta-alanine is a powerful ergogenic aid. This means it can increase an individual's exercise capacity.

It works because it's a precursor to carnosine, a dipeptide molecule your body uses to detoxify lactic acid. Lactic acid accumulation is a major factor in muscular fatigue.[15] So, again, just like we saw with ornithine and ammonia, eliminating lactic acid faster delays the onset of fatigue.

Just as we saw with citrulline and arginine, beta-alanine is a better means of boosting carnosine than carnosine supplementation because the oral bioavailability of the former is so much higher than that of the latter.

Carnosine has another precursor — the amino acid histidine — but supplementation with this amino is virtually never required because histidine naturally occurs at high concentrations in staple foods. So, in practice, beta-alanine is almost always the limiting factor on carnosine production,[16,17] which means that supplementing with it is a great strategy for increasing carnosine synthesis.

Two meta-analyses of more than 40 peer-reviewed studies found that beta-alanine is most effective at increasing endurance during exercises done at an intensity that's sustainable for 30 seconds to 10 minutes.[18] This makes beta-alanine particularly well suited for HIIT-style workouts, or high rep lifting.

Fear not the tingles!

Almost everybody who takes beta-alanine experiences a tingling sensation in their head and torso. If this happens to you, don't sweat it – a safety review concluded that this feeling is perfectly normal and benign.[19]

Note the double dose

The standard dose of beta alanine is 3.2 grams per serving (presumably taken daily), which does effectively achieve carnosine muscle saturation (as demonstrated in the studies cited above).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, you can achieve carnosine saturation even faster by using a bigger dose. Studies done using this 6,400 mg/day dose have found that this dose is capable of increasing muscle carnosine content by 100% within a 2-4 week period.[20,21] And when 6,400 mg is taken daily for more than 4 weeks, the result is a significant improvement in athletic endurance.[22,23]

-

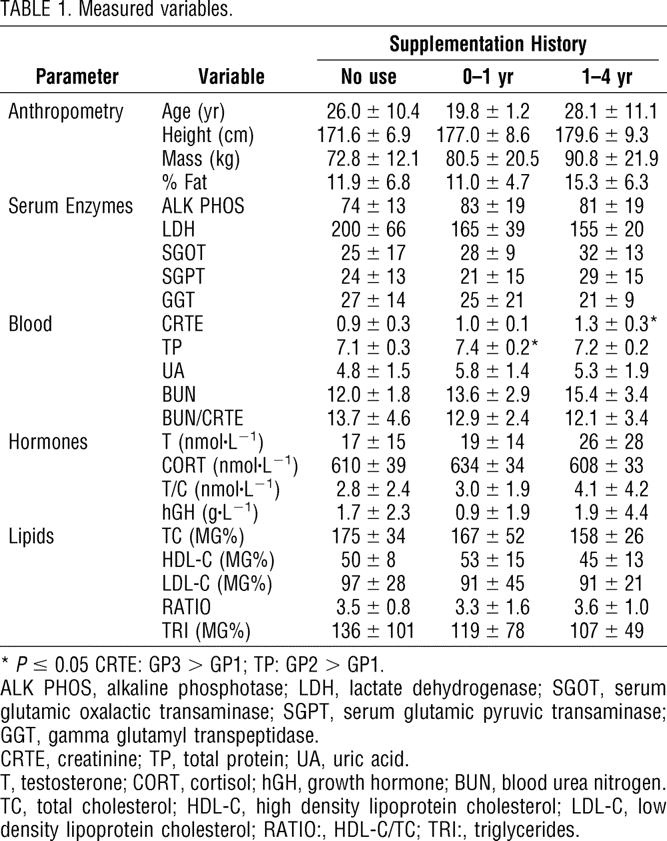

Creatine Monohydrate – 5,000 mg

Creatine is arguably the most studied and ubiquitous sports supplement on the market. Effective, safe, and cheap, creatine is considered an ergogenic aid thanks to its impact on cellular metabolism.

It works by increasing the amount of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) your cells produce,[24-28] a simple but profound change that has tons of second and third order effects, including but not limited to:

- More power output[29,30]

- Increased lean mass[30-35]

- Quicker sprints[36-38]

- Better cellular hydration[39]

- Decreased fatigue[40-42]

- Heightened sense of well-being[42-45]

- Better cognitive performance in vegans and vegetarians[46,47]

- Higher testosterone blood levels[24,48-51]

- Greater bone density[34]

The dozens of studies we've referenced here are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to creatine's evidentiary support. There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of similar studies and meta-analyses in the peer-reviewed literature. Bottom line? If you're taking supplements and none of them are creatine, you're doing it wrong.

-

Arginine Nitrate (as NO3-T) – 3,000 mg

Alright, so we just got done trash-talking arginine's low oral bioavailability – so what the heck is arginine nitrate doing in Ascension?

Amazingly enough, combining arginine with citrulline vastly improves its effectiveness. This is because citrulline inhibits the enzyme responsible for arginine's premature degradation,[52,53] thus increasing the amount of arginine your body is able to absorb. Studies show that arginine and citrulline synergize, meaning that the combination outperforms the sum of the ingredients' individual effects in both human[54,55] and animal[1] research.

And if that's not exciting enough, consider the fact that nitrates are an important NO precursor in themselves, although on a different synthesis pathway than arginine and citrulline. Nitrates are incorporated into the NO molecule by salivary glands in your mouth.[56-58]

Research on nitrates shows that they can have a positive effect on:

- Circulation[59]

- Aerobic efficiency[59-63]

- Strength[64,65]

- Cellular energy production[65-67]

With citrulline, arginine, and nitrates, Ascension already has us set up for an absolutely massive pump.

-

HydroPrime (65% Glycerol Powder) – 2,000 mg

HydroPrime is a trademarked glycerol developed and marketed by NNB Nutrition.

As an osmolyte, glycerol can increase the water content of your cells, thus improving cellular hydration. It does this by manipulating osmotic pressure gradients around your cells – hence the name osmolyte.

Better cellular hydration means your cells can function more effectively in the face of stressors, including heat stress. Better access to water-soluble nutrients means your cells can perform at a higher level, which ultimately has an ergogenic effect at the body level.[68]

Glycerol is loved by weightlifters thanks to its massive pump-inducing ability.[69]

All of this sounds great, right? Using glycerol seems like it should be a total no-brainer. Well, unfortunately, generic glycerol has a big problem: it's hygroscopic, meaning it draws in moisture from the environment. As the glycerol powder inevitably builds up more and more moisture, weak electrostatic forces between the water molecules cause it to clump up, and then eventually, if the process goes on for too long, brick. Once bricked, the glycerol is a solid, unusable mass — and any product it's in is ruined.

So, understandably, formulators and consumers alike have always been hesitant to rely on glycerol.

That is, until NNB developed HydroPrime, a hygroscopically stable form of glycerol. It doesn't clump nearly as much as generic glycerol, and thus, is vastly more shelf stable.

Be sure to take HydroPrime, or any other form of glycerol, with plenty of water.

-

L-Tyrosine – 2,000 mg

The amino acid tyrosine is a precursor to some really important hormones and neurotransmitters.

First, and most relevant to a pre-workout formula, is the fact that tyrosine is the precursor for catecholamine neurotransmitters like dopamine and adrenaline, which are key for optimal focus, motivation, and alertness.[70] Upregulating these neurotransmitters can switch on your sympathetic nervous system, and help your brain access the states of peak focus, motivation, and alertness that you'll need to attempt and complete your toughest workouts.

Tyrosine is also important as a precursor to the thyroid hormones T3 and T4.[71] Supplemental tyrosine can help support optimal thyroid function,[71] especially when the thyroid is under assault by stressors like strenuous exercise and caloric restriction.[71,72]

In particular, tyrosine is great for improving cognitive function during acute sleep deprivation. In fact, studies carried out by the U.S. military found that tyrosine is even better at this than caffeine – high praise indeed![73,74]

-

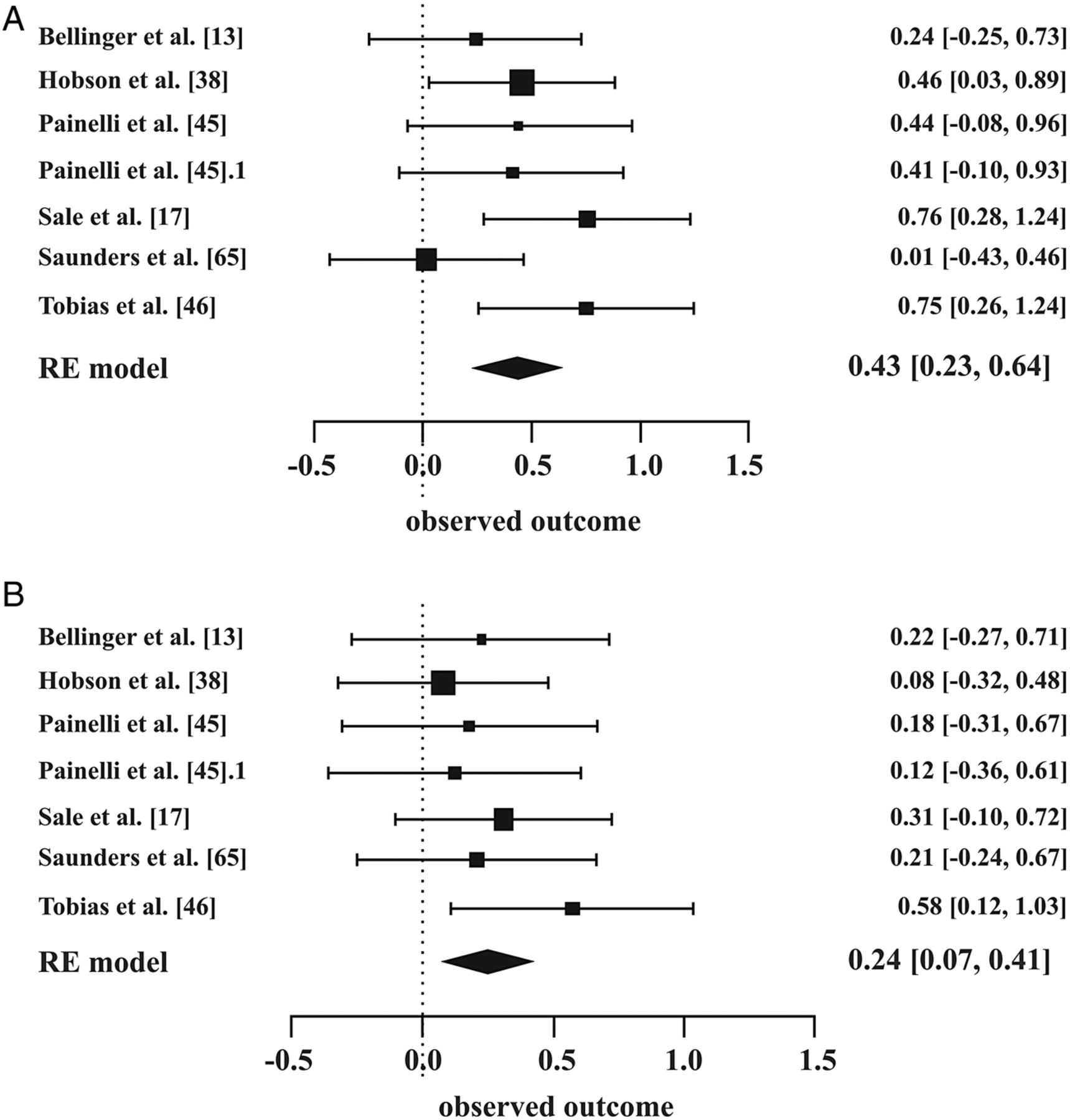

Taurine – 2,000 mg

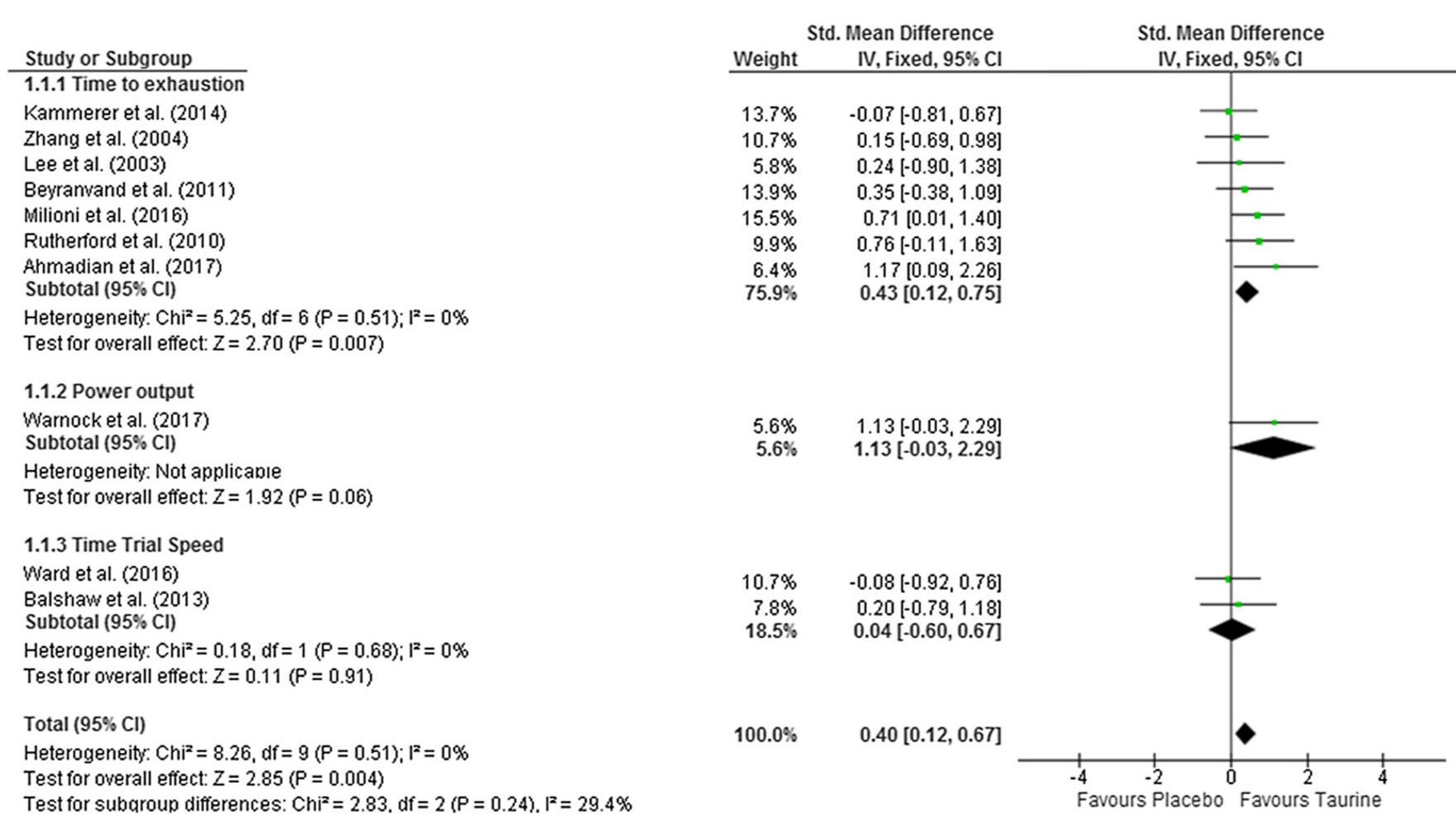

Taurine's effect on endurance, with success in doses anywhere from 1 gram to 6 grams.

Next up is one of the supplement industry's best jack of all trade ingredients – taurine. This amino acid is one of the most multifaceted and, gram-for-gram, efficacious ingredients currently in use.

Much like caffeine (which we'll cover below), taurine has ergogenic, nootropic, and lipolytic (fat burning) properties – without the stimulant effects. Actually, taurine is a great ingredient to combine with caffeine precisely because it helps mitigate some of the stimulant's downsides.

Osmolyte – improves cellular hydration

Taurine is, like HydroPrime, an osmolyte capable of inducing cellular hyperhydration.[75] It confers the same benefits, too. By improving cells' access to nutrients and thermal resistance, taurine helps them work harder and more efficiently under challenging conditions, including heat stress.[76]

By this mechanism, taurine can improve both aerobic and anaerobic endurance. According to a 2018 meta-analysis on taurine, a single 1-gram dose taken just before workouts can substantially increase athletic endurance.[77]

Taurine also plays a supporting role in calcium signaling,[78] thus decreasing the likelihood of muscle cramps.[79]

Neurological benefits

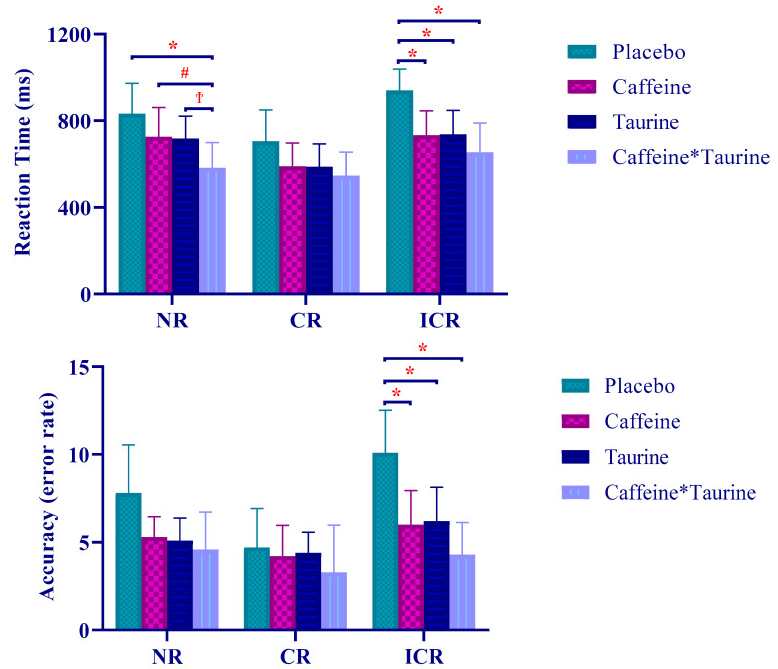

When it came to reaction time and mental accuracy, CAF*TAU absolutely crushed CAF, TAU, and the placebo.

Taurine also has significant antioxidant effects,[80,81] and is particularly good at protecting mitochondria from oxidative stress. As one study puts it, taurine can help defend against pathologies associated with mitochondrial defects, such as aging, mitochondrial diseases, metabolic syndrome, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological disorders."[82]

Taurine is also GABAergic, meaning it exerts the same calming, inhibitory effect on brain cells as the neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). It can thus have an anti-anxiety effect, which is partly related to its ability to decrease neural inflammation.[83]

Taurine also induces mitochondrial biogenesis — the creation of new mitochondria — in brain tissue.[84] As regular PricePlow readers know, we're huge fans of mitochondrial health. It's absolutely essential for general health and longevity.

Finally, taurine upregulates dopamine and protects the health and function of dopamine-producing brain cells.[85,86]

So, taurine is significantly neuroprotective by several key mechanisms. This is an ingredient that can not only help you find the focus and motivation you need to work out, but actually help prevent the drop in cognitive performance that can accompany intense exercise.

Its GABAergic and blood pressure lowering[80] effects make taurine an awesome ingredient to take with caffeine, helping you exploit the upsides of caffeine while minimizing the downsides.

Burns fat

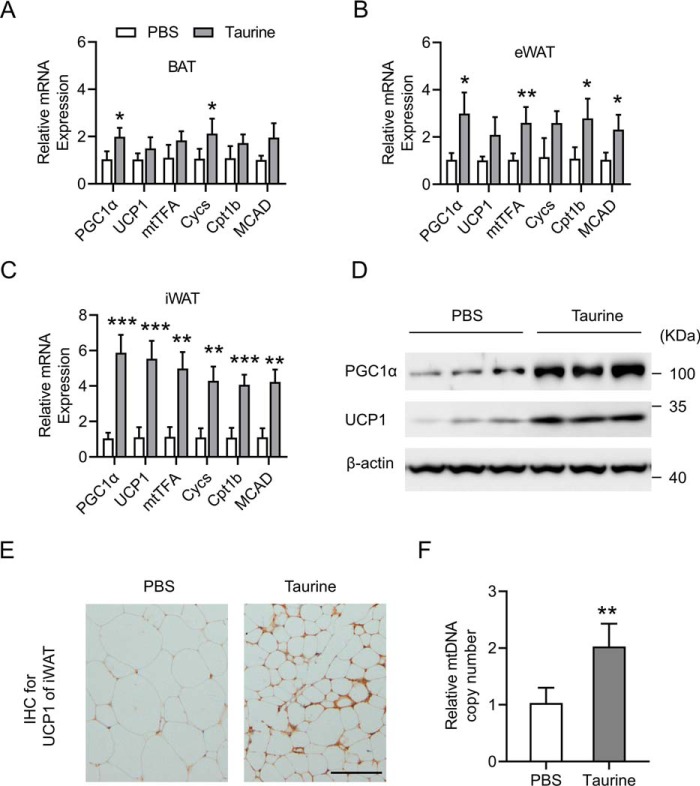

Taurine can induce the browning of fat, which is important because brown fat is more mitochondrial-dense and metabolically active!

And as impressive as all of that is, taurine can even help you improve your body composition as well. That's because taurine is able to convert white adipose tissue (WAT) to brown adipose tissue (BAT).[87,88]

WAT and BAT are your body's two basic kinds of adipose (fat) tissue – they differ essentially in mitochondrial density, with BAT having way more mitochondria than WAT. It's metabolically active, meaning that unlike WAT, BAT burns significant amounts of calories.

BAT burns calories through a process called non-shivering thermogenesis (NST), in which energy substrates like glucose and fatty acids get turned into heat. As you can probably guess, NST is one of the metabolic processes your body uses to maintain its core temperature when subjected to cold.

Bottom line, the more BAT you have, the more calories you can burn in a day.[89] This works best if you pair high BAT content with deliberate cold exposure.

Because BAT takes up glucose and fatty acids to burn through NST, it can decrease the concentration of glucose and fatty acids in your blood, leading to better glycemic control, cholesterol, and insulin sensitivity.[90]

Taurine is a jack-of-all-trades

So, you can surely understand why we love taurine – its capability for increasing both physical and mental performance makes it an indispensable tool in any athlete's arsenal. In our opinion, the best thing that taurine does for the Ascension formula is synergize with caffeine. This interaction is why you usually see caffeine and taurine combined in energy drink formulas.

Taurine is conditionally essential, which means that if you're demanding a lot of your body, extra taurine is definitely called for.[77,83,84]

Taurine's benefits are dose-dependent, so we love seeing Ascension use a 2,000 mg dose instead of the typical 1,000 mg.

-

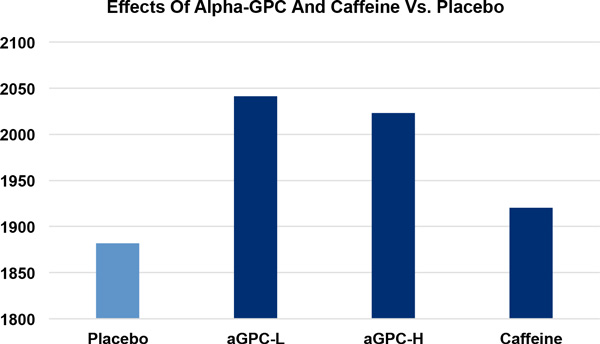

Alpha-GPC 50% – 600 mg

AlphaGPC is a form of choline, a B vitamin your body needs to help construct and maintain the phospholipid bilayer membranes that comprise the outer layer of all your body's cells.[91] It's also necessary for the intercellular signaling functions those membranes are responsible for performing.[91]

Caffeine and Alpha GPC are great for brain boosting, but they're also awesome for enhancing performance.

Choline is a necessary precursor to acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that facilitates learning and memory.[92] We usually refer to acetylcholine as the learning neurotransmitter – it's that important for proper cognitive function.

Taking choline can increase your body's production of acetylcholine, creating better-than-normal cognitive performance.[93,94]

Choline is also a crucial methyl donor that participates in methionine metabolism. This is important because excess methionine buildup is associated with cardiovascular disease.[95]

Alpha-GPC is our favorite form of choline because, unlike other forms of choline, it's capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier[96] and exhibits high oral bioavailability.

-

VasoDrive-AP – 508 mg

VasoDrive-AP is made up of two tripeptide proteins derived from casein. These lactotripeptides (LTPs) are isoleucyl-prolyl-proline (IPP) and valyl-prolyl-proline (VPP).[97]

This ingredient increases vasodilation by upregulating NO via endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme that synthesizes NO within your arteries.[98] It has this mechanism in common with citrulline and arginine nitrate, which we covered earlier.

More unusually, and perhaps more interestingly, VasoDrive also inhibits vasoconstriction, the mechanism by which your arteries constrict. This has the same net effect as increasing vasodilation, improving circulation and helping increase athletic performance.

The LTPs in VasoDrive stop vasoconstriction by downregulating an enzyme called angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE).[97] This is the same mechanism of action common to the most widely-prescribed blood pharmaceutical blood pressure medications.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials found that casein-derived LTPs can decrease blood pressure to roughly the same extent as more battle-proven NO-boosting ingredients. It found that, on average, LTP administration decreased systolic blood pressure by approximately 3 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure by roughly 1.5 mm Hg. In some of the studies under review, it caused reductions of 10 mm Hg or more systolic, and 6 mm Hg diastolic.[97]

Just to put those numbers into perspective, citrulline – an NO booster we all know and love – can decrease systolic blood pressure by roughly 4 mm Hg on average.[99]

-

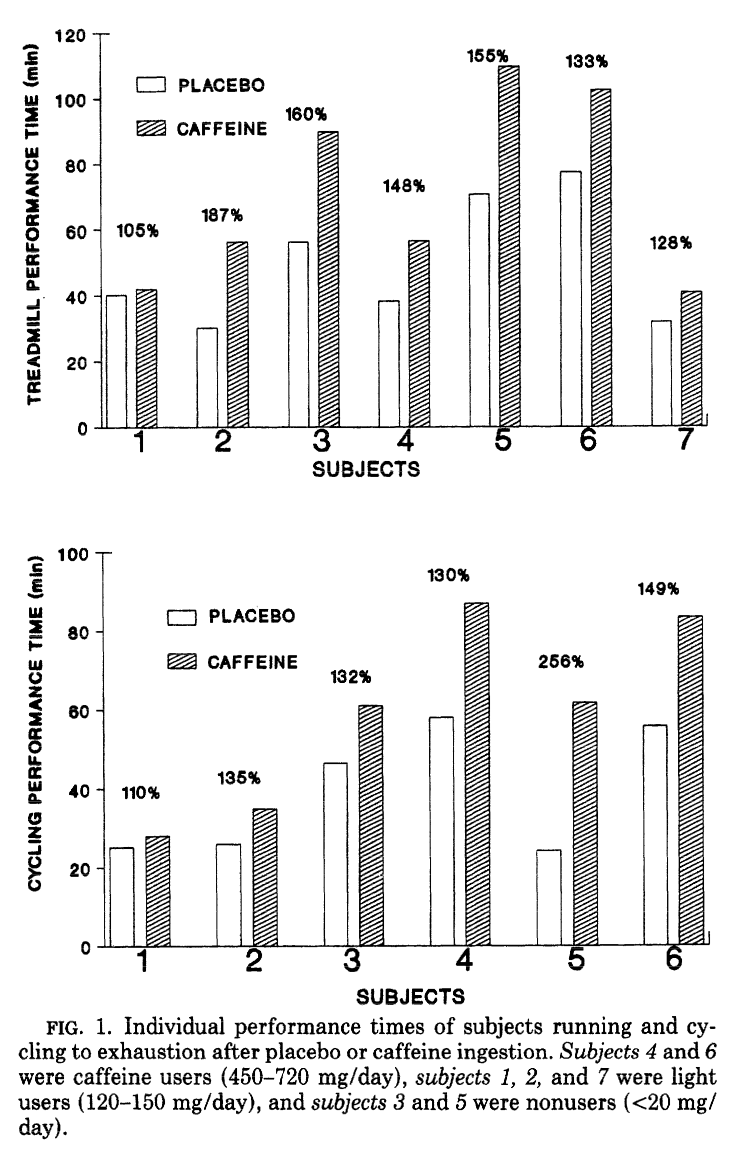

Caffeine Anhydrous – 300 mg

The methylxanthine stimulant caffeine can, thanks to its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, exert a high degree of activity in the brain. Because of this, caffeine administration can cause significant boosts in mood, focus, energy, and physical performance.[100,101] Anhydrous caffeine, being rapidly absorbed, is the form used when the goal is fast action, a big initial jolt of energy that can be used to initiate tough exercises.

Known since 1991, very high dose caffeine can seriously boost performance. As you can see, it's quite variable amongst users - future research would show that caffeine's effects depend on your genotype.

Caffeine is famed for its anti-fatigue effects, which are produced by caffeine's ability to inhibit the action of adenosine, a byproduct of normal cellular metabolism that builds up in the body while you're awake and leads to feelings of tiredness. Under normal circumstances, the more adenosine you've got in circulation, the more tired you'll feel,[100] but caffeine administration stops adenosine from creating this effect by blocking the adenosine receptor.

Caffeine can also speed up cellular metabolism by downregulating phosphodiesterase, an enzyme that breaks down cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Inhibiting this enzyme causes cAMP levels to go up, and since cAMP instructs your cells to burn calories for energy, cellular metabolism goes up.[101-103]

Fat burning is where caffeine really excels – it can increase your body's rate of fat burning by roughly 50%.[104]

Because of its effect on cellular-metabolic function, caffeine can improve several dimensions of athletic performance, including strength, speed, and endurance.[105]

-

zum-XR (yields 70% caffeine) – 135 mg

Paired with the 300 mg of caffeine anhydrous is 135 mg zum-XR, an extended-release form of caffeine.

The idea here is that while anhydrous provides a rapid initial jolt, it tapers quickly, leaving the user open to severe withdrawal symptoms. Thus, zum-XR is here to manage withdrawal by gradually entering the bloodstream as the anhydrous wears off. In short, this leads to a smoother energy curve and a more pleasant overall caffeine experience.

Note that this brings the total caffeine content up to 435 mg!!! This is a big dose, and if you're not sure whether you can tolerate it, do NOT use this product without first consulting your licensed medical expert.

-

Bitter Orange Extract (Citrus aurantium) (30% Synephrine) – 100 mg

Bitter orange extract naturally contains not one, but two bioactive molecules that can help accelerate fat burning.

First we have synephrine, an alkaloid that is known for its ability to increase metabolic rate by its beta-3 adrenoceptor agonism, a mechanism that not only speeds up metabolism but also reduces blood glucose by stimulating insulin secretion.[106] As a result, synephrine promotes fat burning for energy.[107] One study found that synephrine supplementation can increase daily caloric expenditure by as much as 183 calories per day![108]

Synephrine has this mechanism in common with the infamous stimulant ephedrine — but don't worry, it's far less taxing on the cardiovascular system than ephedrine[109,110] and even other, less stimulatory bioflavonoids.[111]

Synephrine doesn't just directly increase the number of calories you burn in a day, though. It can also have an indirect effect on metabolism via ergogenic mechanisms, increasing power output and volume during exercise.[108]

The second bioactive in this ingredient is another alkaloid called hordenine. It's a beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist[112] Just like synephrine, it directly increases basal metabolic rate.[113]. Hordenin is also a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI),[114,115] meaning it can help improve feelings of energy, motivation, and focus by increasing the activity of key neurotransmitters.

-

CognatiQ (Coffea arabica) (Whole Coffee Fruit Extract) – 100 mg

CognatiQ is a coffee cherry extract designed to naturally contain high amounts of bioactive constituents that upregulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).[116] You can think of BDNF as fertilizer for neurons, helping them survive, grow, and differentiate, even in adults.[117,118] Exercise itself can significantly upregulate BDNF, so pairing it with a healthy dose of CognatiQ is giving you a nootropic double-whammy.[119]

According to a 2022 research review on BDNF, "During exercise stimuli the BDNF contributes directly to strengthening neuromuscular junctions, muscle regeneration, insulin-regulated glucose uptake and β-oxidation processes in muscle tissue."[120] In other words, it promotes both the integrity and performance of your musculoskeletal system.

Interestingly, BDNF can also promote metabolic flexibility, the ability of your cells to toggle between fat and glucose burning to meet their energy requirements.[120]

CognatiQ has a big impact on BDNF levels.O ne study found that the standard 100 mg dose can increase BDNF by an incredible 150%.[116]

-

Huperzia serrata Extract (leaf and stem) (1% Huperzine A) – 20 mg

Huperzine A is the primary bioactive constituent of Huperzia serrata. It upregulates acetylcholine, but rather than doing so by increasing production, it inhibits acetylcholine breakdown by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.[121] Note that this sets up a nice synergistic dynamic with alpha-GPC. While the choline from alpha-GPC increases production, huperzine A extends the lifespan of that extra acetylcholine.

Huperzine A can trigger neurogenesis, the growth of new neurons.[122]

-

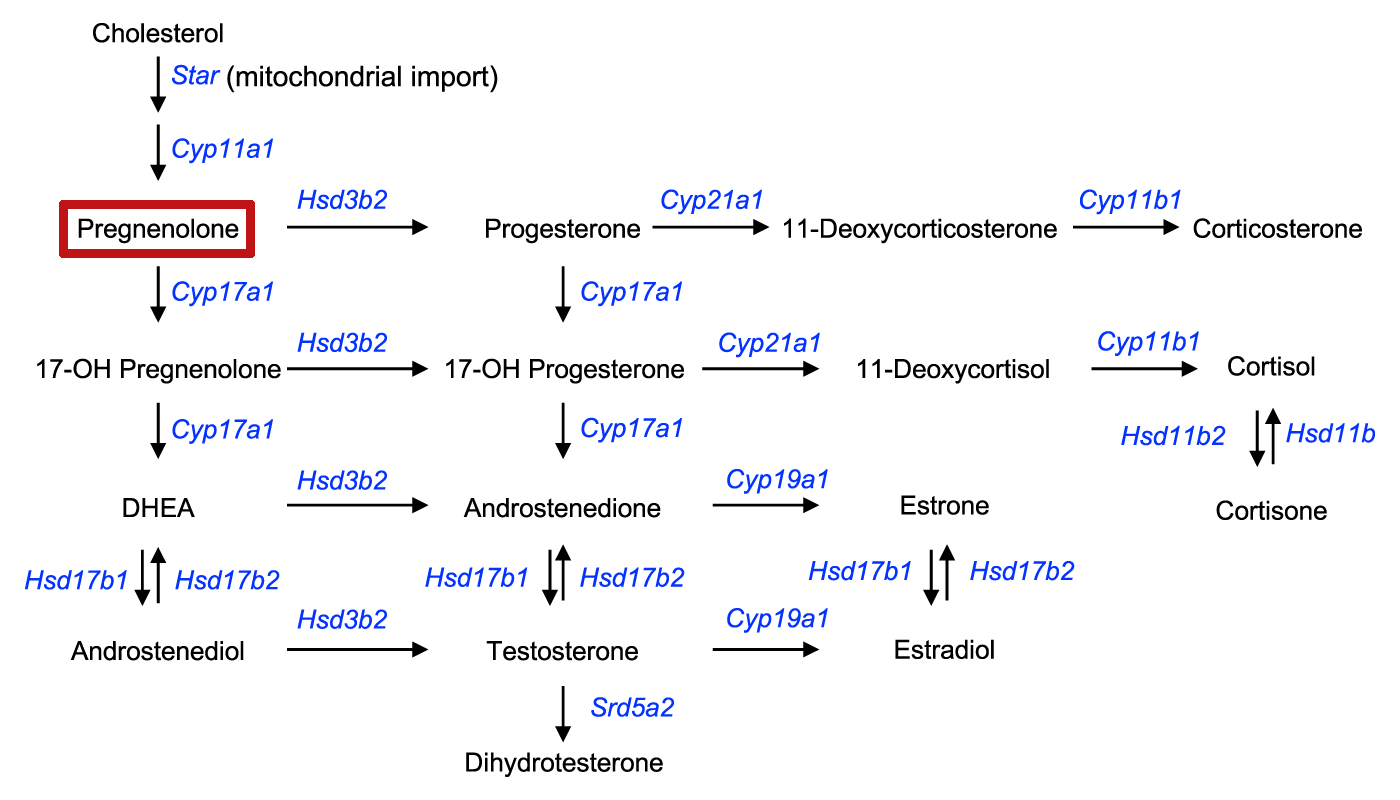

Pregnenolone – 10 mg

Although pregnenolone is still a relatively obscure ingredient, it's arguably one of the most important. This is a pro-hormone that serves as a precursor to all other steroid hormones, including testosterone, esterogen, and DHEA.[123]

Pregnenolone is the starting point of all steroid and neurosteroid synthesis. Annotation in red ours.

Pregnenolone is the beginning point of all steroid synthesis pathways.[123]

Pregnenolone is itself a neurosteroid, with important protective effects on the brain.[123] It's also dopaminergic. Yet, pregnenolone also supplies your body with the raw material it needs to synthesize all other steroid hormones! For instance, progesterone, one of the primary pregnenolone metabolites, has been shown to increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) production, which, again, helps promote the growth of and connection between neurons.[124]

Animal research has demonstrated that pregnenolone can even increase acetylcholine production to the extent of improving visuospatial intelligence.[125]

-

Rauwolscine (Rauwolfia vomitoria Root Extract)(Std. Min 90% rauwolscine) – 2 mg

Rauwolfia vomitoria contains rauwolscine, an alkaloid that's sometimes called alpha yohimbine because the two molecules share mechanisms of action. Both rauwolscine and yohimbine are considered alpha-2 antagonists, which means that they trigger adrenaline and noradrenaline receptors, thereby imitating the action of those neurotransmitters.

Thanks to this, yohimbine and rauwolscine can both decrease appetite,[126] facilitate fat loss,[127] and enhance focus.[128] Rauwolscine also inhibits fat storage while increasing the amount of energy your body has available to burn.[129,130]

Note that individual tolerance of rauwolscine varies widely.

-

Magnesium (as Magnesium Citrate) – 125 mg (30% DV)

Magnesium plays an indispensable role in a huge range of metabolic processes. Magnesium deficiency can cause your brain's hypothalamic-pituitary axis to become unbalanced, which is a big issue since the HPA is implicated in stress hormone (cortisol and adrenaline) synthesis.[131] In fact, HPA dysfunction is a huge risk factor for insomnia and[132] it's associated with chronic stress and anxiety issues.[133-135]

What makes magnesium such an important point of leverage is the bidirectional relationship between stress and magnesium – low magnesium causes high cortisol, but high cortisol causes the body to lose magnesium.[136] Magnesium supplementation can thus break this vicious cycle and help restore normal stress response.

-

Other Ingredients:

-

Potassium (as potassium citrate) – 308 mg (7% DV)

-

Sodium (as sodium citrate) – 178 mg (8% DV)

-

Currently Available Flavors

Conclusion

It's been a long time since we saw a formula with such a huge number of ingredients, and what's more, all the dosing here is awesome. Not only is nothing underdosed, but almost everything is dosed as aggressively as the peer-reviewed literature supports. Because the doses used are so huge, you could half-dose this supplement and still enjoy major efficacy. This is a big win for consumers!

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)