If you've been dieting or using supplements over the past few years, then there's no way you've missed this aggravating situation:

Protein prices are constantly rising.

Things got especially bad when Gatorade started adding whey protein to their recovery sports drinks -- a decision that threw massive ripples into the entire market.[1,2,3]

To combat these high costs and to make up for protein's terrible profit margins, some supplement companies have found a way to game the system -- in a completely legal manner.

The only victims? You and me, the loyal consumers.

In this article, we're going to explain what these companies are doing, how it's legal, and most importantly... how to avoid it.

The TL;DR

This is a long article. The more we researched this, the uglier things got. Here are the bullet points:

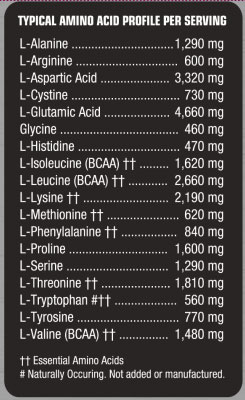

- Some companies are adding extra amino acids such as taurine, glycine, glutamine, and creatine to protein powders.

- Due to the FDA's extremely loose and haphazard definition of "protein", this practice is technically legal.[6,8,12]

- Products with creatine in them are by far the worst, most misleading offenders.

-

Learn how to read the label here. In short:

- Never buy protein with creatine in it

- Strongly avoid protein products with taurine, glycine, or gluamine in the ingredient listing...

- ...unless the full amino profile is disclosed and it looks natural.

-

Not sure who to trust or what to buy?

Take our Buyer's Guide questionnaire, "What's the Best Protein Powder -- For YOU", to get a personalized recommendation.

-

Major Update: Class action lawsuit filings are underway! Body Fortress, GNC, and a few others have had class action complaints filed against them! See them all here.

- What we're doing about it and how you can get involved here.

- There are also likely products that contain these aminos and do not list them. We can hardly scratch the surface on that situation without extensive amounts of testing.

- Update: We've received an absolutely phenomenal response from an experienced industry insider. You can read it here.

They are counting those added aminos as dietary protein on the label, even though they're not nearly as beneficial as real food-based protein.

This saves them big money because these added minos are very cheap.

Taurine.. Glycine... What are these doing in my protein shake?!

Along with those price hikes, perhaps you've also noticed a few new ingredients in your protein powders lately -- most notably taurine and glycine, but a few others as well.

So what's the big deal here? After all, taurine isn't a bad ingredient. It’s actually very useful, and definitely not at all dangerous.

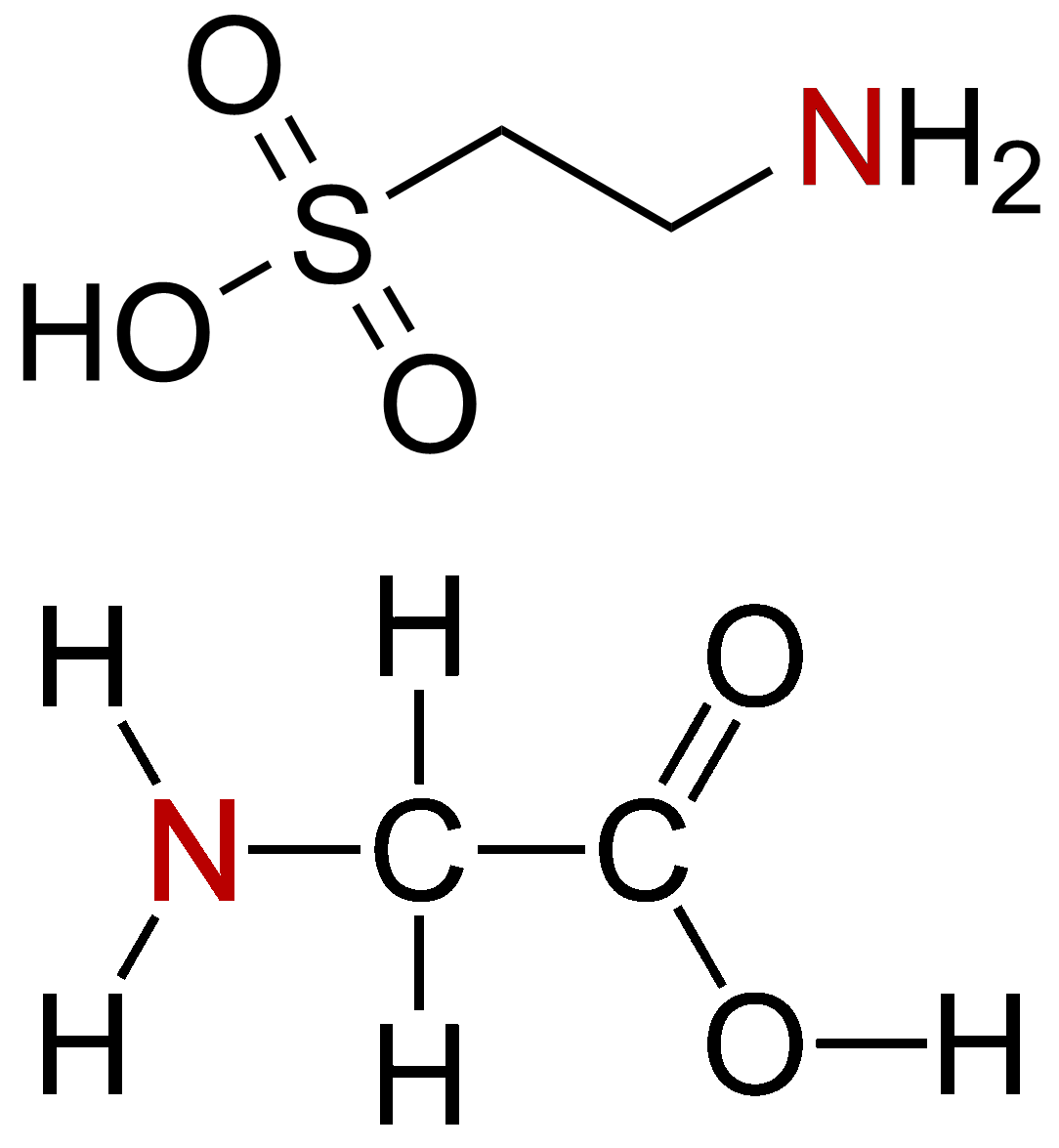

The Taurine and Glycine Molecules. Those nitrogen bonds in red have been causing us a whole bunch of problems... keep reading to understand why.

"Not in my protein"... right? After all, your tub says 25g protein right on the label!!! This is a major product from a big company - they can't lie like that and get away with it! They're cGMP certified and have lab tests to back up their numbers!

Well, guess what: When run through a certificate of authenticity (CoA) test, glycine and taurine show up as nitrogen. And because of that nitrogen-based bond, they are technically considered "protein" to the FDA.

Meaning, according to FDA specifications, you do have "25g of protein" — tested, certified and stamped for approval.

Except one thing...

Instead, you're getting a fair amount of cheap filler that qualifies under the FDA's loose definition of protein - but it's not going to do much for your muscle protein synthesis.

This has been happening for a while now

This is not new news - as early as 2012, the development sent shockwaves through the industry. Insiders and the most educated of consumers have known about it for a while.

But since the problem still persists years later, it's time to bring it back to the forefront. We're finally posting this in hopes that you'll share it, ask questions, and contribute to the conversation.

But it gets worse before it gets better...

It's not just taurine and glycine. Any added free form amino acid can be used to cheat the system like this -- including glutamine and glutamine peptides. Even creatine, which is possibly the worst offender, as we'll see below.

Note that we're not upset when a manufacturer adds in extra leucine -- this is the powerhouse amino acid linked the growth and repair of your muscle tissue -- but glutamine, glycine, and taurine... they're just not as effective.

In short, we've been had by the companies that are adding these amino acids to our protein powders - and right before our very eyes, no less.

Why would they bother?

Money! Why else?

Taurine and glycine are very inexpensive, so this helps the manufacturer's bottom line.

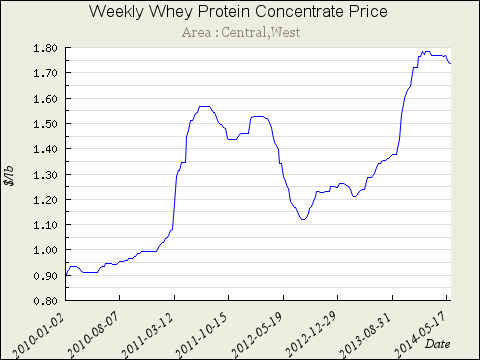

For example, bulk WPC-80 (the good whey protein concentrate) currently costs between $1.75 and $2.00 per pound, which is up over 30% year over year and double from this time in 2009.[2,3]

There's been some nasty swings in the past five years, but the overall trend is up and to the right

Taurine, on the other hand, can be found for a conservative $0.45 per pound. That data is from Alibaba, so it's likely the prices can be found for even less.[4] Glycine fares similarly.[5]

Update: These prices are being heavily disputed. More on this later, but the point is, they're cheaper than quality whey. See the industry insider's response here

Using this simple model, taurine is 4x cheaper per pound than WPC. Whey protein isolate costs even more, and the prices don't seem to be letting up.

Add in flavoring, packaging, and distribution, and what you get is exactly what we've seen - skyrocketing protein prices over the past few years. In order to keep up, manufacturers had some difficult decisions to make, many of which were made without your athletic goals in mind.

CREATINE also throws off tests - in a major way!

A few companies have used these revelations as an educational marketing tool, with varying degrees of success.

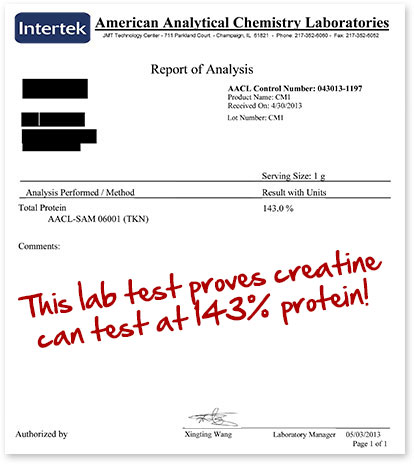

A lab test where creatine somehow registers as an impossible 143% protein

Why? Because creatine contains several nitrogen bonds, and that's how protein is currently measured. We explore the details in the next major section.

To the right, you can see the rather comical lab test done on a competing product.

Stay away from creatine in protein products

We love creatine... but not in our protein products. It's simply there to buffer profit margins and screw with testing even moreso than normal.

So when a protein product has creatine in it, and the formula isn't 100% transparent, we literally have zero clue what's going on with the product -- especially when mixed with other free form aminos.

The bottom line

Companies can save a lot of money by substituting high-priced protein for a few grams of inferior amino acids and still stay compliant by the letter of the law.

How can they do that? Isn't that what the FDA is for?

The FDA's laws and guidelines, as they stand in 2014, did not foresee this mess, and are long overdue for update.

There are three main issues at hand:

-

The FDA guidelines contain logical loopholes

According to the FDA, pure amino acid products are not counted as protein, but nothing is specifically stated regarding protein that includes extra amino acids.

To see this, find the FDA's Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Part 101 (Food Labeling), section 101.36 (Nutrition labeling of dietary supplements), which specifically talks about supplement labeling[6]:

21 CFR 101.36(b)(2)(i) 12. May I declare protein on the label if my product contains only individual amino acids? No. You may not declare protein on your products that contain only amino acids.

Clear as mud? Basically.

If you look closely at the FDA's wording, you can see that there's ample room for interpretation.

The definition of how the FDA determines nitrogen/protein in your food is not publicly available.

Since protein powders are not products that contain only amino acids, a company can interpret this to mean that added amino acids can be included as part of the overall protein content.

This basically means that a relatively pure amino acid product such as Cellucor's Alpha Amino cannot claim to have protein. But it doesn't say anything about a manufacturer taking a protein-based product and adding amino acids that technically fall under the definition of "protein"... even though they're adding aminos that are not the dietary type of protein we've come to expect when attempting to build or keep lean muscle.

While this form of reasoning is actually a logical fallacy known as denying the antecedent[7], it still provides enough ambiguity to cover these actions.

-

The FDA's definition of protein isn't even set by the FDA, and it's nowhere to be found online

The above guideline makes things confusing, but the real nail in the coffin is how the FDA treats protein as a macronutrient in foods.The sad truth is that the FDA doesn't even define it themselves! They pass the buck to a company named AOAC International, referencing their 1990 guideline that is based on a protein test invented in the 1800s!

Our above quote about the supplement labeling cited above (from Title 21, Part 101, section 101.36) is part of a much bigger document regarding the labeling of all foods for human consumption.

Under section 101.9 (Nutrition labeling of food), part (c)(7), discusses protein:

... Protein content may be calculated on the basis of the factor of 6.25 times the nitrogen content of the food as determined by the appropriate method of analysis as given in the "Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC International" (formerly the Association of Official Analytical Chemists), 15th Ed. (1990), which is incorporated by reference in accordance with 5 U.S.C. 552(a) and 1 CFR part 51, except when the official procedure for a specific food requires another factor.[8]

Emphasis ours. So the method of protein analysis is set by the AOAC.

By definition, someone could add fertilizer to your whey protein and call it protein.

Looking for the "Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC International", 15th Edition, AOAC.org won't be much help to you. Instead, they'll try to sell you the current version (19th edition from 2012).[10]

Thankfully, it can be found mirrored in two separate places - Archive.org[11] (text version) and Public.Resource.org[12] (PDF version).

But something's amiss - in the index at the back of the PDF, we learn that the pages we need (regarding protein in food and dairy products) are actually in the second volume - around page 802. Volume I only goes up to page 684.

Volume II of the 1990 edition is not publicly available!

And this is where we hit a dead end. The second volume, which has the page we need, is nowhere to be found.

Maybe you can find it with your finest Google-fu. The keywords we're essentially searching for are official methods of analysis aoac international 1990 15th volume ii -- You can mix and match those as best you can, but our team hasn't been able to find it online.

So, in summary, the definition of how the FDA determines nitrogen/protein in your food is not easily publicly available. Not just supplements - but food in general.

Let's assume it's the Kjeldahl Method

We're going to take a small leap of faith and guess that the AOAC is using the Kjeldahl method as its definition of protein in milk, dairy, and dairy-based supplements. After all, nearly all nitrogenous protein measurements in Volume I use it, and they still refer to it in their most recent documents and methodologies.[13,14]

So what is the Kjeldahl method?

This is a test that is used to determine how much nitrogen is in a chemical substance. Nothing more, nothing less. It was invented by a Danish chemist named Johan Kjeldahl in 1883.[15]To this day, this man is still measuring your protein and your gains

That's around the time when the first light bulb was invented.

While this method works excellently for measuring nitrogen, it's extremely outdated when it comes to dietary protein - the thing we're interested in. It's a decent ballpark estimate, but it's too easy to game, since so many compounds contain a nitrogen bond.

By definition, someone could add fertilizer to your whey protein and call it protein.

That might sound far fetched, but it's exactly what happened with the melamine Chinese milk powder scandal in 2008. In that scandal, 54,000 babies were hospitalized due to adulterated baby formula that was spiked for the very same reasons we're seeing today in our protein.[16]

While that scandal ended with two executions[17], we don't think taurine/glycine in our protein powder will make so many headlines.

But for those of us who are serious about our athletic training, it should. This method of measuring protein is simply no longer acceptable.

-

Converting nitrogen to protein is a sloppy, estimated, and outdated science

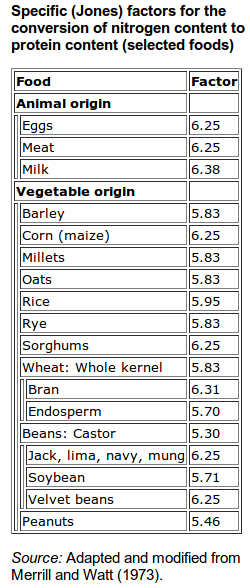

To make matters even worse, the AOAC/FDA standardizes on 6.25 as the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor for foodstuffs. This means that if you take the total nitrogen content and multiply by 6.25, you'll get the amount of protein.

Where does the 6.25 number come from?

6.25 is actually an estimation! The average nitrogen content of proteins was found to be about 16%, which is why 6.25 is used (1 / 0.16 = 6.25).[20]Not all proteins are the same. Should they be treated as such?

Different foods actually have different conversion factors. For instance, eggs are 6.25, but milk (which more closely resembles whey) is actually 6.38. Not an enormous difference, but other amino acids are 5.6, which is a major difference.[20]

So 6.25 is a close estimation... what's the point?

Now you can see that when we're talking about protein, we're really throwing estimations on top of a foundation that's already pretty shaky.

This gives manufacturers yet another chance to game the system. You can get away with using less of an amino acid that's "nitrogen heavy", and have it count as even more protein than you're getting.

Let's take glycine, for instance. The formula is C2H5NO2 and the molecular weight is 75.0666g/mol. Do some high school chemistry, and we arrive at the fact that glycine is 18.66% nitrogen by mass.[21]

This means that for every gram of glycine, Kjeldahl registers 1.19g of protein!

To be fair, we must note that taurine is a "weaker" spiking agent. 1 gram of Taurine registers as 0.714g of protein according to Kjedahl.

But creatine? With the formula of C4H9N3O2, those three nitrogen molecules wreak total havoc on Kjeldahl -- 1 gram of Creatine monohydrate registers as 1.8g of protein with Kjeldahl! (Creatine anhydrous would be 2.05g)

By the way, remember the whole melamine fiasco above? 67% nitrogen by mass! You may or may not agree, but are you starting to understand why China executed the offenders?

Why not fix it? Because industry scientists are... lazy

The entire food industry has avoided changing each food to a more specific set of standards because, we quote one study verbatim, "scientists fear opening the Pandora's box."[19]

Indeed, it would take a massive amount of work to label things appropriately, especially when nitrogen content is already imperfect. That'd be like duct-taping a broken rotary phone.

It took a Freedom of Information Act Request to provide the above methodology

In case you're curious, 5 U.S.C. 552(a) in the FDA's regulations means that the AOAC information was only included due to a Freedom of Information Request.[9]

Why was the AOAC methodology not disclosed in the first place? What did the FDA have to hide? And why is it still literally impossible to find the actual testing methodology?

Every which way we turn, this entire situation just stinks more and more.

Now that you know what's going on, the next step is to avoid it:

How to Read the Label

First, let us note that amino acid spiking occurs when extra free form aminos (or creatine) are added to the mix.

If a protein manufacturer is being responsible and listing the product's full amino acid profile, it will state that there's glycine and glutamine / glutamic acid inside. After all, they're naturally occurring in your protein.However, taurine is not naturally occurring in whey protein in any significant quantity. If you see it on the amino acid profile, it's likely been added. A little bit is fine, but more than a gram of it per scoop is unacceptable.

Where it gets ugly

The real trouble starts when you see any free form amino acid added to your protein's ingredient listing, and there's no amino acid profile on the label.

At this point, it's next to impossible to tell how much of your whey protein is really whey protein and how much is just filler amino acid content. So the best thing to do is avoid it completely.

Realizing your protein is spiked

We typically see two situations:

-

The disputed amino acid is within a "protein blend"

In this case, you'll see a product whose label looks something like this:

Protein Blend (Whey Protein Isolate, Glutamine Peptides, L-Leucine, Egg Albumen, Whey Peptides, L-Isoleucine, L-Valine), Cocoa (Processed With Alkali), etc etc etc

-

The disputed amino acid comes after the dietary proteins

Here's an example:

Protein Blend (Whey Protein Concentrate, Brown Rice Protein Concentrate, Whey Protein Isolate, Egg Albumin, Milk Protein Isolate, Partially Hydrolyzed Whey Protein), Taurine, Glucose Polymer, Cocoa Powder (Dutch Process), L-Glutamine, etc etc etc...

In either example, it's really not possible to tell how much "watering down" is being done, because the whole batch of ingredients are counted as "proteins". For all we know, they could each be in equal dosing!

In the second example, however, we can be relatively confident that there's at least not TOO much L-Glutamine, as it's coming after the cocoa powder. But that's not the cause for taurine, which is listed before "glucose polymer" (also known as maltodextrin).

You can do a bit of math on this product's label to determine roughly how much taurine is in there, but we won't speculate because there's still no way to be sure.

Fact is, we don't know enough to make an educated guess as to this product's true worth. The only solution is to not buy it and not support the companies doing this.

The Basic Rule of Thumb

First off, never buy protein with creatine inside.

1 gram of Creatine monohydrate registers as 1.8g of protein with Kjeldahl

So, if you don't want this extra stuff in your protein, the rule of thumb is to simply not buy any product where aminos like taurine, glycine, glutamine, or creatine have been added to the ingredient listing without a full amino acid profile disclosure.

But if taurine, glycine, or glutamine are listed well at the end of the product list, or after the flavorings... then chances are you're not getting too bamboozled, and it's worth buying if it's on steep discount.

Pro-Tip: Find the French Label

If you're curious about a certain protein supplement that is produced by a major international brand, you might want to check if it's available in France. Certain European countries such as France require full amino acid disclosure, so check Google Images for a French label to see if you can determine just how bad the situation is.[Source Required]

An argument in favor of taurine and creatine

It's worth discussing the other side of the argument:

One could easily take the position that the addition of taurine and creatine (say at 2g each?) are actually going to show a better (and more observable) benefit to an athlete than a true, 100% pure macro peptide-based protein, since taurine is not found in whey/casein at all and creatine is the best ergogen on the planet.

If you have no other source of either of those ingredients, that's very well true. But shouldn't it be for the consumer to decide? When we use supplements that have proprietary formulas utilizing spiking practices, we aren't in full control of our macros. That's a situation athletes should ever put themselves in.

What we're doing about it

First off, we're maintaining this document, and will keep it up to date with as much information as possible. We will leave everything open to critique and commentary.

Above, we educate you on label-reading, and lower down, we provide you with a template of questions to ask your protein manufacturer.

PricePlow's position

With regards to our presence in this industry, we will do our best never to willingly promote or "rank" products that are potentially spiked with amino acids, both across our site and across our partner network.

For instance, on our protein powder page, we will never willingly allow an amino acid spiked product to be anywhere near the top of the listing, unless it's in "hot deal mode" and we believe the price is so low that it's worth buying (at which point we'd warn you if it was potentially spiked).[23,24]

On our partner network, when bloggers and social media personalities use our tools to display the best deals on featured protein products, their sites will also never show any potentially spiked products -- unless the blogger goes out of his or her way to show them.

This is worth fighting for

We love this industry and believe that there are plenty of ethical, beneficial products worth promoting. Those are the products that deserve to be at the top of our listings. We discuss this in greater detail elsewhere on this site.[22]

However, PricePlow will still list potentially spiked products on the site. We're just not going to make it as easy for anyone to find them.

If you're not sure, just contact us or leave a comment and add to the discussion.

Non-affiliation with brands - only the stores

It must be mentioned that we are not affiliated with any supplement manufacturer, and receive no commissions from them. None of them knew beforehand that we were writing this document.

We are, however, affiliated with most stores listed on this website.

This allows us to be as unbiased as humanly possible when it comes to reviewing products, but our store affiliations are something we must disclose.

If you want to use our site, but do not want us to profit off of your purchase, we will set up a new tracking link and gladly donate the commissions to a charity we can both agree on. We currently work with the Vitamin Angels.[25]

Is this that big of a deal?

A few grams of protein isn't really the end of the world. According to the response we received from an industry insider (posted below), you still need at least about 20g of protein to get the right consistency - so you're most likely not getting a totally "empty" product.

But it's not necessarily about the protein. It's about the ethics.

The real problems are:

- Nobody wants to get bamboozled - not even a bit.

- The good companies the are not doing this are at a severe pricing disadvantage.

- The FDA is relatively benign when it comes to handling these types of situations.

And that's why it's time we all stood together and started taking matters into our own hands.

Class action lawsuits have been filed against brands

Several class action lawsuits have been filed against various brands, and several more are on the way. This section will be updated with all known suits:

- July 1, 2014: Body Fortress Lawsuit

- November 4, 2014: A GNC and 4 Dimension Nutrition joint class action

- November 11, 2014: The CVS Lawsuit was filed regarding CVS Whey Protein Powder.

- Giant Sports (Delicious Protein)

- November 13, 2014: Inner Armour Class Action Lawsuit (Mass Peak and Nitro Peak) -- Update September 9, 2016: Case dismissed with prejudice

- November 19, 2014: New Whey Lawsuit (Multi-Pro)

- November 19, 2014: Pro Supps PS Whey Lawsuit served.

- November 19, 2014: Fit Foods (Mutant Whey)

- ALLMAX Lawsuit (Hexapro Protein Powder)

- January 23, 2015: CytoSport Muscle Milk Family Lawsuit (note that this is not for spiking! It's allegedly just under-dosed protein and not having L-Glutamine!)

- January 28, 2015: MusclePharm Arnold Schwarzenegger Iron Mass

A single legal firm is behind these, and we expect more before the end of 2014.[26] Even though we've demonstrated the technical legal basis for the spiking, there is still much to be argued over the misleading intent by certain manufacturers who have taken things to the extremes.

We're unsure how any of these will be settled, but we hope that ultimately, the industry gets cleaned up, one way or another.

Stay in the know

So who or what can I trust?

To make a good recommendation, it really depends on your specific needs. To address this, we created a Best Protein Powder "flowchart" / questionnaire.

The page linked above will ask you a bunch of questions, and then make a decision based upon your dietary needs. We will keep it updated as more and more brands get third party testing.

Trusted, Spike-Free Lab Test Results

Sadly, five years later, most companies still don't publish 3rd-Party lab tests on a regular basis!! One that does is NutraBio, who announced publishing all third party lab tests from every batch using an external lab in 2017.

Who are the Guilty Parties?

We're not going to name names here, because several companies have reformulated their proteins over the past year and it's tough to keep everything up to date.

Instead, we urge you to learn to read the labels, or simply ask the manufacturer. If you don't get a satisfactory answer, then the decision to walk is yours.

What do I ask my protein manufacturer?

Here is a madlib for you to fill out and ask your supplement manufacturer:

Hi [Protein Manufacturer], my name is [Mike] and I'm a customer of yours. I noticed that you have [taurine/glycine/glutamine/creatine] listed on the label for [Protein Product Name], yet you are not disclosing the exact amount.

[Protein Product Name] supposedly has [25g] of protein. Are you willing to state whether or not the [taurine/glycine/glutamine] is included in that [25g]? If so, how much of it is [taurine/glycine/glutamine/creatine] and how much is actual dietary [whey] protein?

Until I hear back with a satisfactory answer, I will no longer buy any of your protein products.

Thank you very much for your time, [Mike]

Replace everything in [brackets] to suit your needs.

What about when free form amino's are added but not on the label

This is, in fact, the bigger issue at hand. But unfortunately, it's one that very few people will touch.

The reason being, if you get a protein product tested and publish the data, you open yourself up to a massive slew of lawsuits.

Furthermore, the brand may not even know their products are spiked. If they're receiving bulk protein from another source (which has spiked it), and the above tests all pass, even they themselves would have difficulty knowing it's been spiked without more intensive testing.

More intensive testing on all raw materials received would then cut into their bottom lines, slow production, and set them back even further against the competition who's not doing it.

It's an awful situation, and sadly, in 4500 words, we've merely scratched the surface here.

How can we solve this problem and be more aware?

If there's interest, we can start a petition and lobby our local congress and FDA representatives, asking for a more clear definition of the word protein.

Given the current state of affairs in our government, we're less than hopeful anything will be accomplished, especially when other massively powerful companies such as Dupont have complained as early as 2000.[18]

Despite the massive growth of this industry, it seems that the FDA still mainly cares mostly about the sales of pharmaceutical drugs.

Instead, we believe it's best to take things into our own hands, spread the word, and vote with our wallets. If enough people contact these manufacturers, we may be able to initiate change sooner than the government.

This is worth our time. You are worth our time.

When we talk passionately about this situation, we don't think about the 32 year old guy who's making good money and hitting the weights a few times a week.

We think about the 18 year old kid who's scraping together every last bit of his money to buy protein from a brand that he idolizes. We think about how he's struggling to make gains and how he needs every last bit of help he can get.

He's the one we're fighting for. He's the one who's worth fighting for.

Thanks for taking the time to read this. All comments are welcome. -Mike and the team at PricePlow

Update: Industry Insiders RESPOND

An industry veteran with large amounts of experience in this area sent us a phenomenal email to clarify some major points. They do not wish to be named, and we will respect that decision.

Dear PricePlow:

The pricings you cited in your recent blog post regarding taurine and glycine are not reflective for current market conditions in the United States.

At the moment, the price for Taurine per kilogram is $3.35-$3.85 per kilogram in the Continental United States. While it may be as low as $1.00 per kilogram in China when purchased in 50,000 kilogram to 100,000 kilogram quantities? The costs associated with freight are not included in this. This would include multiple truckings to and from ports in China and the United States as well as "on the water" charges, etc.

If I could could purchase Taurine at the price quoted on your website here in and at the United States then I surely would open a Taurine-only brokerage and just sell Taurine to companies. Surely, I would retire a multi-millionaire in under a year.

I also suggest that you investigate "Chinese Glycine Dumping" scandal. Some places for you to point your browser are:

https://enforcement.trade.gov/frn/summary/prc/2012-29543-1.pdf

https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-04-08/html/2013-08108.htm

Because of tariffs imposed to punish China for "dumping" glycine into the United States, the price of glycine has increased and it has become difficult to import direct into the United States from China.

I suspect that much of the glycine ending up in the United States "makes it way from China to some other country" first, gets repacked and reshipped to the United States. While glycine is an inexpensive amino acid, it is not as inexpensive as your website implies.

There are additional, mitigating factors regarding this so-called "protein spiking" situation that PricePlow has failed to address.

Such factors include, but are not limited to:

- Has PricePlow considered that even if a brand does not list "creatine, glycine, taurine, glutamine, etc." on their label that one or more of those ingredients maybe found in the product anyhow? [Editorial note: we added some commentary late, after the fact]

- Regarding Point# 1, It is possible a brand may not even be aware of this even if it is happening with their labeled product. A brand may contract with a manufacturer who may add amino acids to a formula while withholding this information from the brand. If the brand then tests for total protein content per cGMP standards using the AOAC method explicit in the law.

The laboratory analysis may read that indeed, the product meets specification because the method listed in the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, Part 110 specifies this is the way a company should test for total protein content. For the record, this is the sole and only way written into the law that a company may utilize and be considered compliant.

The absence of glycine, taurine or creatine on the product label should not be considered irrefutable evidence that these are not contained in the product.

- Have you considered that sometimes when protein is manufactured it will not meet the legal specification to make a label claim. For example, "WPC80" by definition has to be >80% protein.

There will be batches of protein intended to meet this standard that do not - perhaps they only test out at 77% protein? This should not be labeled and sold as WPC80. There is nothing wrong with it other than it being 3% underweight in the protein count or it may have a bit too much fat or ash. This protein should be destined to be sold as animal feed at 1/3rd the price of WPC-80.

What if a protein producer has an "off batch" that is very close? Perhaps a large batch intended to be WPC80 test out at 75% total protein count? The moral hazard certainly exists here to just "add in a little bit of glycine, taurine or creatine" to enrich the batch so it will retest at better than 80% total protein count.

So even the most respected brands that purchase container loads of protein direct from the huge protein suppliers may end up with glycine, taurine and creatine in their "WPC80" they did not intend to see in there and are unaware of. When the mandated AOAC testing method for total protein is run on the product the results will come back as the product meeting specification.

- You also failed to mention that per federal law the only way to test foods - and dietary supplements are foods - for total protein count is by the AOAC method (the N = 6.25 method, I believe the law requires the Dumas Method and not Kjeldahl Method as you wrote). Testing by any other method than what is written into the law could put a company in non-compliance with cGMP's and in violation of federal law.

Companies have no choice in the matter if they follow the law and wish to be cGMP compliant. That is the law as written.

Quite clearly, it is evident what this does to a brand or manufacturer. Even if the brand or manufacturer desired to deduct the added amino acid content from the total protein count this is not allowable per federal law.

Any company that does such may be guilty of mislabeling, can be subject to FDA action and even sued via class action for adulteration or misbranding.

The sole and only acceptable and recognized method to test is AOAC (Dumas Method) total nitrogen test using the 6.25 multiple against a sample of the actual product being sold, irrespective of whether this is a finished product sold to end users or an intermediate, raw material being sold to a brand or manufacturer. No other method is allowable per federal law. None.

- The FDA is not to blame for the above situation in Point #4. Remember, it is Congress that writes the bill and the President who signs it into law.

The protein industry is a mess but as you can conclude from this correspondence? This mess does not originate with the brands or manufacturers.

It runs much deeper than that and the initial issues are with the way the United States Code reads under 21 CFR 110 (cGMP for Foods) and 21 CFR 111 (cGMP for Dietary Supplements).

I hope you will consider editing your article a little to reflect some of the issues I mention here.

Regards, [Name withheld upon request]

Going a bit further, they state why the situation can't be that bad:

Realistically, you have to have at least 20g of "protein" in the mix per serving or it will not have the creamy, rich, mouthfeel of a protein powder. You can't really get under the 20g level of "protein" without the product really having obvious holes in the flavor, consistency, etc.

A second industry insider response

Another insider contacted us via Facebook, discussing something else that's not really touched upon here: the difference between various forms of whey protein concentrate.

See it below:

A note on your comments in that same article regarding whey protein concentrate. There actually is no regulation as to the protein level for WPC80. It is called whey protein concentrate 80%, but there are very few sources of an 80% on the market. Over 90% of all WPC80 currently being manufactured averages between 74% and 78% protein content. This level has dropped over the years because dairy manufactures can produce more WPC per pound of raw whey.

Many companies use the "dry basis" test result for protein label claim, but that is not the actual value of protein in the product, the "As Is" basis must be used which is always 3-4 points lower.

Here is the biggest scam that your customers should know about: WPC 34. This whey protein is only 34% actual protein. The supplement industry has decided that WPC34 should be labeled "Whey Protein Concentrate" on supplement facts panels, the exact same designation as WPC80. So the consumer does not know whether they are getting a 34% whey concentrate or an 80% whey concentrate.

This buy the way, is what makes amino spiking work so well. WPC34 is 1/3 the cost of WPC80. Use WPC34 in a product with a little WPI just for show and the product is cheap as hell to manufacture. Of course the protein content will be way to low and the consumer will notice. But not once you add the aminos in to spike it back up. That's the part of the scam that you are missing in your article.

WPC34 is sold out in this country, its fool’s gold, and brands are legally using it every day. Here’s the best part: When you use mostly WPC34 which is higher in fat, you can add all those aminos back in and still have the creamy mouth feel of a legitimate whey protein powder. The consumer will never know.

Our response to this is that there are now a few protein powders that actually state the exact type of whey protein concentrate on the label. The one product line that we can mention here on a regular basis are the NutraBio protein powders, due to their publishing of 3rd party lab tests. They constantly come up in our top protein powders list.

He then continued:

I have been trying to publicize this for years. I've been working on the industry to set self regulated standards for labeling practices.

The important changes that I would like to see is the removal of Proprietary blends from labels, elimination of amino spiking, a separate designation for whey protein concentrate 80 vs 34. As far as the WPC80 is concerned, even if the 80 is on the label, that doesn't mean the product has to be 80%. WPC80 is used as a classification for whey concentrates that average in around 80%, but very few on the market today are.

10 years ago the average protein level in WPC was 4-5% higher as was WPI (whey isolates), but as the demand grew for both, the manufacturers who do the filtering have stretched the material by lowering the yield of protein.

Thanks again for reading! Feel free to add more comments below or join us for further discussion on social media!

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)