Every once in a while, we get some true sparks of innovation in the athletic supplement space. Interspersed among a sea of copycat formulas and commodified products, there are diamonds in the rough that hold a promise to advance the entire industry in a single leap.

There's perhaps nobody better suited than Matt Karich and Soul Performance Nutrition to hit on these unique formulas. Back in May of 2022, we went live with Matt in Episode 68 of the PricePlow Podcast, going on a deep dive regarding his Soul Performance brainchild, discussing the level of precision and testing he's bringing to the industry.

Instead of just treating the symptoms of joint pain, Solace Joint Care targets the root, systemic inflammation behind it. This provides short-term joint comfort and long-term joint health.

Their latest product exemplifies this experimental ethos perfectly.

Engineering a Novel, Top-Shelf Joint Supplement

Solace Joint Care was engineered with one major goal in mind: to target systemic inflammation and to treat both short-term joint-comfort long-term joint health.

Throughout its design, Matt found that optimizing for this target -- inflammation -- would be the best way to combat poor joint health. The resulting formula contains some standard joint health ingredients along with some novel ingredients that have the potential to turn proper joint health on its head.

We're going to get into a deep dive on each ingredient, but for those who want the cliffnotes, here's a summary:

- Caraflame Complex is an anti-inflammatory blend from NutraShure that contains ingredients like sodium butyrate, lycopene, astaxanthin, and more, which all work in concert towards one purpose: reducing inflammation and helping to resolve the underlying causes behind joint pain.

Solace Joint Care is the first joint supplement to include SmartPrime-Om to combat overzealous inflammatory omega-6 pathways

SmartPrime-OM Complex is another blend from NutraShure that targets inflammation specifically via moderation of the Omega 3 to Omega 6 ratio by adjusting the body's metabolism of both classes of fatty acids. We've seen this in top-tier fish oil supplements and are now very excited to have it in a joint supplement.

- Levagen+ is an ingredient composed of palmitoylethanolamide, with LipiSperse as a delivery agent, that helps reduce inflammation in part due to its ability to downregulate inflammatory cytokine production, and in part due to its upregulation of the endocannabinoid system, which has been shown to reduce symptoms of joint diseases like arthritis.

- Curcuwin Ultra+, drawn from turmeric root, has a long history of use for its anti-inflammatory properties. This form is stated to be 144 times more bioavailable than standard curcumin.

- Hyaluronic Acid is a lubricating substance that is found naturally in joints, and has been supplemented for joint health for years.

Again, we're very excited to see SmartPrime-OM in a joint supplement - especially one that's BSCG certified like all Soul Performance Nutrition supplements.

Let's check prices and availability through PricePlow, and get into the details:

Soul Performance Nutrition Solace Joint Care – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming Ingredients video.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Solace Joint Care Ingredients

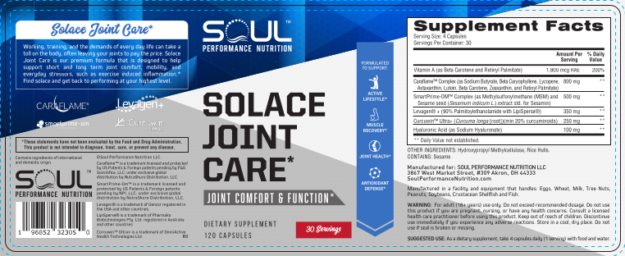

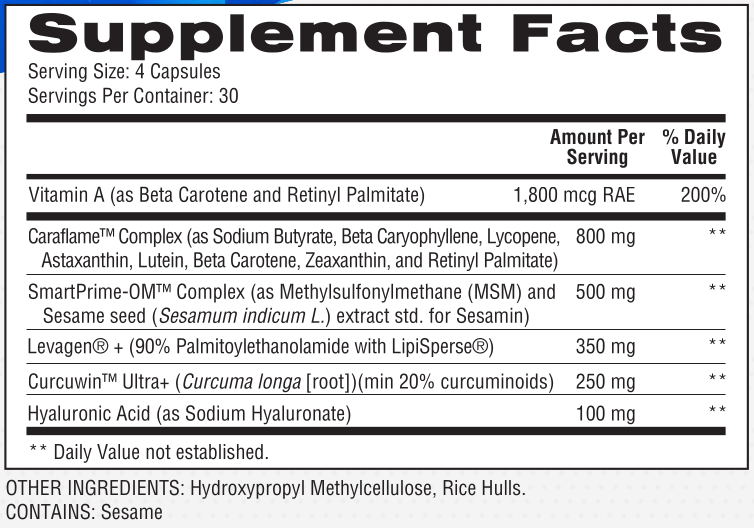

In a single 4-capsule serving of Solace Joint Care from Soul Performance Nutrition, you get the following:

-

Caraflame Complex (as Sodium Butyrate, Beta Caryophyllene, Lycopene, Astaxanthin, Lutein, Beta-Carotene, Zeaxanthin, and Retinyl Palmitate) – 800 mg

Inflammation generally spells disaster for your joints.

The current state of inflammation

Although science has traditionally divided arthritis into inflammatory and non-inflammatory subtypes, this paradigm has come under scrutiny in recent years. More and more evidence is emerging that osteoarthritis, which accounts for most of what's called "non-inflammatory arthritis", is indeed exacerbated by, and may even be caused by, systemic inflammation.[1,2]

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disorder in the United States,[3] and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune joint disease that most of us have heard of, damages joints through inflammation.[4] Anti-inflammatory drugs are the first-line treatment for OA and RA alike.[5,6]

So there's a legitimate argument to be made for whether you're trying to deal with existing joint pain or prevent it from developing in the future, keeping inflammation under control should be one of your top priorities.

That's where the Caraflame Complex from NutraShure comes in.

This blend consists of powerful anti-inflammatory ingredients that can potentially help manage the underlying cause of many crippling joint symptoms.

-

Sodium butyrate

Butyrate, also known as butyric acid, has been studied extensively for its anti-inflammatory effects.

Animal studies have shown that butyrate can significantly reduce circulating levels of interleukin 8 (IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).[7] Both of these molecules are inflammatory cytokines that are elevated in people with both OA and RA.[8]

The general nature of butyrate's anti-inflammatory effects can be inferred from the fact that it also seems to improve symptoms of colitis and proctitis.[9-11]

Butyrate also seems to help manage symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS),[12] a condition with a known inflammatory component.

-

Beta Caryophyllene

The aromatic sesquiterpene beta caryophyllene (BCP) is widely distributed throughout the plant kingdom, and is present in many popular foods and spices. For example, it's one of the primary bioactive constituents of black pepper,[13] a powerfully anti-inflammatory spice.

BC activates cells' CB2 cannabinoid receptors, which are known to have anti-inflammatory effects.[14] In particular, BCP seems to reduce circulating levels of the following inflammatory factors:[14]

- Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)

- Interleukin-1β (IL-1β)

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

- Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB)

As we discussed above, TNF-α seems to be involved in severe inflammatory conditions. IL-6 is elevated in OA, and IL-6 blood levels positively correlate with the severity of disease.[15]

A 2019 animal study found that monotherapy with BCP reduced paw thickness and arthritic index in rats, an effect that's apparently related to BCP's ability to downregulate TNF-α.[16]

Thanks to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, BCP also seems to have anti-diabetic and neuroprotective effects.[17,18] One paper takes pains to point out that BCP seems to help help improve mitochondrial function, which is huge for overall health and longevity.[17]

-

Lycopene

Lycopene, an antioxidant compound that occurs naturally in tomatoes, is famed for its ability to improve prostate health. But did you know it's a powerful anti-inflammatory compound?

In fact, lycopene's ability to downregulate many of the inflammatory cytokines we've already discussed – including various interleukins (TNF-α) – is key to its prostate health benefits.[19]

The anti-inflammatory action of lycopene isn't localized to prostate tissue, though. Blood lycopene levels are inversely correlated to blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), one of the primary biomarkers for systemic inflammation.[20]

-

Beta-carotene

One great thing about lycopene is that it has synergistic effects with beta-carotene, a reddish-orange carotenoid pigment that famously gives carrots their color.

Together, lycopene and beta-carotene suppress inflammation to a greater degree than either compound alone. This combination has been shown to downregulate not only TNF-α, but also cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), an enzyme that creates inflammatory prostaglandins.[21] The action of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like aspirin and ibuprofen work by targeting the same pathway.[22]

Note that beta-carotene is also a vitamin A precursor, so supplementing with it can help you meet your vitamin A recommended daily intake - this and another ingredient below will contribute to your daily intake, as shown on the top portion of the label.

-

Zeaxanthin

With zeaxanthin, we have another anti-inflammatory carotenoid capable of downregulating interleukins and TNF-α.[23]

Zeaxanthin blood levels have been shown to inversely correlate with C-reactive protein levels,[24] and zeaxanthin has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease.[23] It's also popular in eye support supplements.

-

Retinyl palmitate

Retinyl palmitate contains retinol, the active form of vitamin A.

Given the state of the modern American diet, it probably won't surprise you to learn that 45% of Americans are said to be deficient in vitamin A.[25] For those affected, that can be problematic for joint health in the long run, since vitamin A deficiency can cause systemic inflammation.[26]

The above combine to form a powerful new anti-inflammatory ingredient, and it's further bolstered by our attack on the overindulgence of omega-6 fatty acids with SmartPrime-OM:

-

-

SmartPrime-OM Complex (as Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) and Sesame seed (Sesamum indicum L.) extract std. for Sesamin) – 500 mg

SmartPrime-Om from NutraShure is a patent-pending blend of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds that affect polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) metabolism. By changing the expression of certain genes, SmartPrime can actually increase the body's metabolism of omega-3 fatty acids, while decreasing its metabolism of omega-6 fatty acids.

This matters because although human beings consumed omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids at about a 1:1 ratio in our ancestral environments,[27-30] modern Americans consume 15 times more omega-6 than omega-3![31]

Unfortunately, such a skewed omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio contributes to chronic systemic inflammation. It's not surprising, then, that the research shows excessive consumption of omega-6 is associated with some devastating health outcomes.[32] For example, eating too much omega-6 relative to omega-3 is closely associated with serious mental illness,[33,34] cardiovascular disease,[35] diabetes,[36,37] and obesity.[38,39]

The big underlying mechanism here is probably omega-6 PUFA's ability to induce profound insulin resistance.[40,41]

So how do we fix this?

The most obvious solution is eating less omega-6 and more omega-3, or minimizing overall polyunsaturated fatty acid intake.

But let's face it, this is quite challenging in our modern food environment. Although we, here at PricePlow, as well as most of our readers, do our best to eat this way, things inevitably slip through the cracks.

That's where SmartPrime comes in – it can help improve our omega-3:omega-6 blood ratio, even without a dietary change. And with that can come some serious promise in the fight against inflammation.

How SmartPrime Works

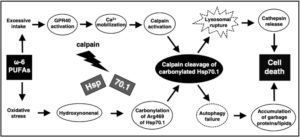

Out of the scope of this document, but the Omega-6 Calpain-Cathepsin Hypothesis of cell death is one theory explaining the molecular cascade originating from n-6 PUFAs that causes cell death,[42] implicating it in many diseases.

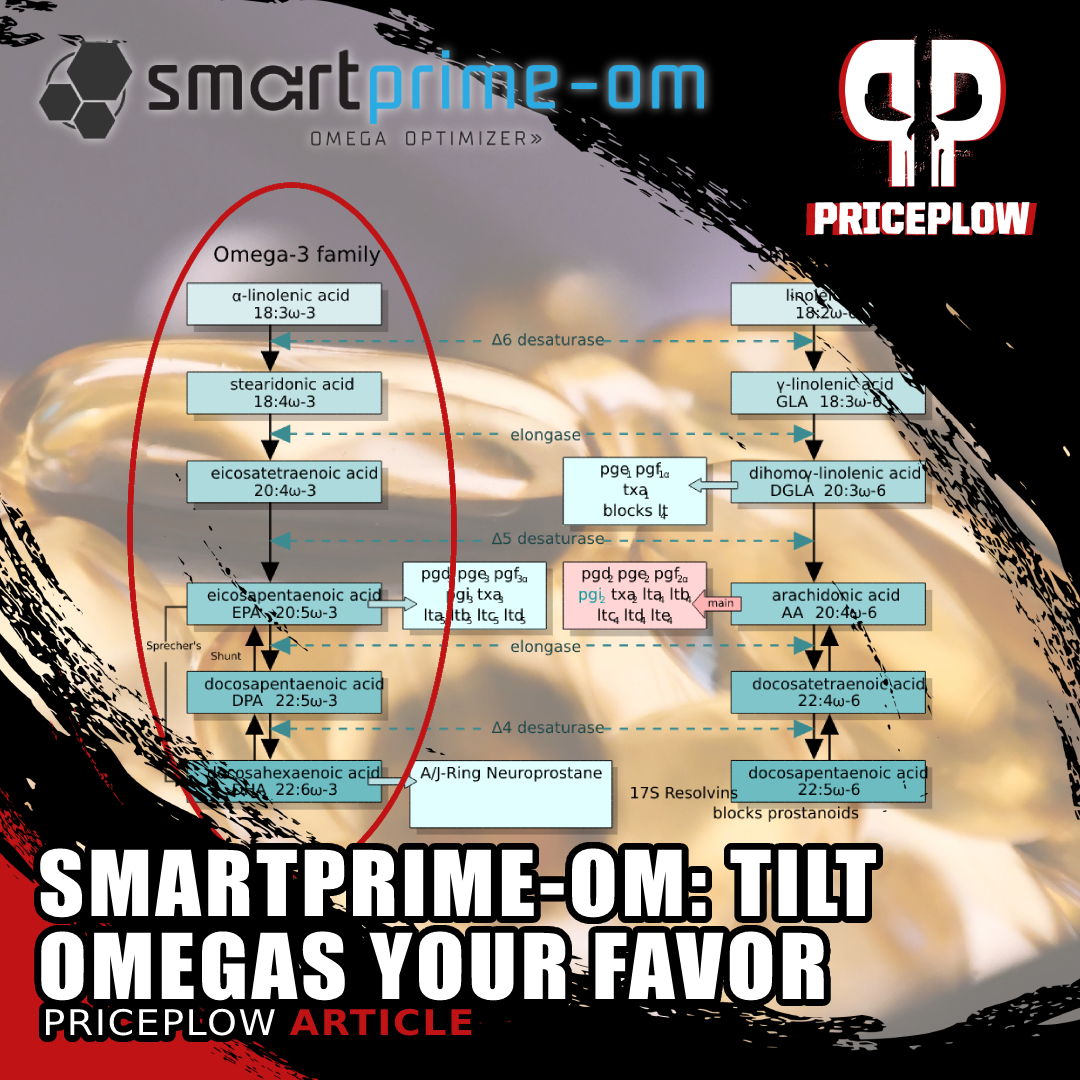

SmartPrime's main bioactive constituents are lignans. These polyphenolic antioxidants occur at high concentrations in the seeds of certain plants, including sesame seeds, which is where SmartPrime's lignans come from.Impressively, the lignans used have been shown to change the epigenetic expression of the genes that the body uses to process the omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids we consume.[43]

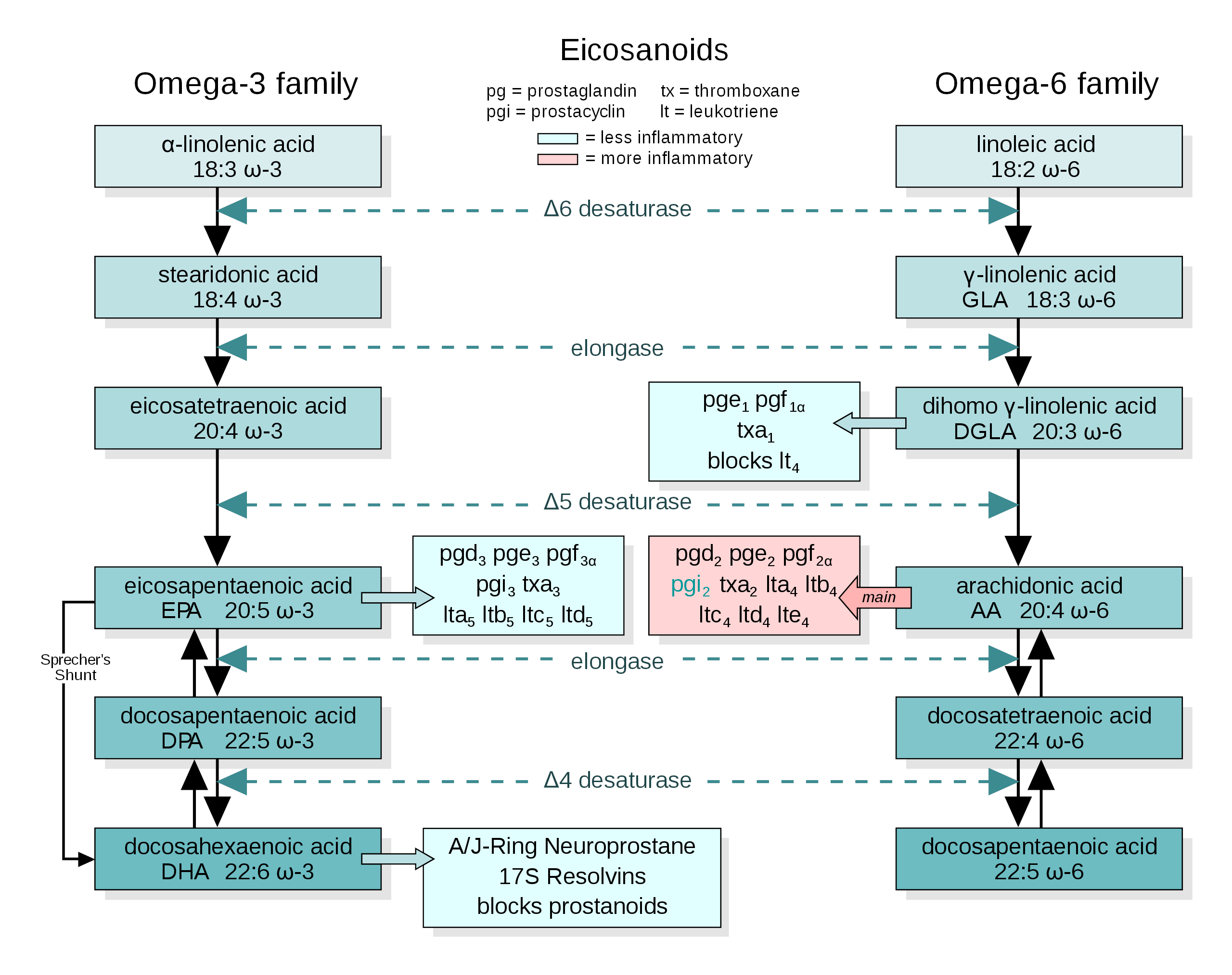

Generally speaking, the PUFAs we eat are what we call omega-3 or omega-6 precursors – this means that once ingested, they're converted by your body's metabolic machinery into different PUFAs, which we generally refer to as "PUFA end products".

Encourage omega-3, discourage omega-6

Each PUFA precursor and PUFA end product has different effects on human biology, and generally speaking, the end products have stronger effects than the precursors themselves. This means that we can improve the health and function of the human body by influencing the process of PUFA conversion.

Specifically, we want to encourage the production of omega-3 PUFA end products, while discouraging the production of omega-6 PUFA end products.

That's exactly what SmartPrime is designed to do.

As it turns out, the same enzymes are responsible for your body converting omega-3 and omega-6 precursors into end products.[44]

The amount of omega-6 and omega-3 PUFA you consume isn't the only factor in your body's omega-3:omega-6 status: the activation of PUFA enzymes matters too. This enzymatic PUFA metabolism is what SmartPrime is designed to improve. Image courtesy of WikiMedia

For example, delta 6 desaturase converts alpha-linoleic acid, an omega-3 precursor, into stearidonic acid. But the very same enzyme is also responsible for converting linoleic acid (an omega-6 PUFA that's extremely abundant in our food supply) into gamma-linoleic acid.

In practice, this means that alpha-linoleic acid and linoleic acid are competing for access to the delta 6 desaturase enzyme. That's why the dietary ratio matters so much: Statistically speaking, the more alpha-linoleic acid you have floating around relative to linoleic acid, the more frequently delta 6 desaturase will be activated by alpha-linoleic acid.

So let's see how we can encourage the reactions on the left side of the above graphic -- the omega-3 pathway.

Sesamin

Sesamin has been shown to inhibit the enzymatic conversion of omega-6 fatty acids, but not the omega-3s.[45-47]

This means that at every step of the PUFA metabolic pathway, the body's ratio of omega-3 end products to omega-6 end products increases, culminating with a significant increase in your body's production of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)[46-48] – the final omega-3 PUFA end products. At the same time, your body should produce less pro-inflammatory omega-6 end products, like arachidonic acid.[46-48]

That's exactly what we want to happen. But SmartPrime's creators also realized we needed some more methylation support to optimize the effect:

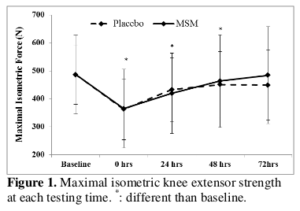

Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM)

The other important ingredient in SmartPrime is methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), an organosulfur compound that acts as a powerful methyl donor and sulfur donor. This matters because your body needs methyl and sulfur groups to produce omega-3 PUFA end products.[49-51]

Competitive athlete/lifter who needs to get back to full-strength ASAP? One of the MSM Benefits is that it can get you there sooner... and with less pain!

Independent studies have shown that sesame oil and MSM, when consumed together, can significantly enhance cholesterol and triglyceride status in diabetic mice, an effect driven largely by an improvement in their underlying PUFA metabolism.[52,53]

MSM's independent benefits for joint health

MSM consists of about 34% sulfur by weight, which doesn't just help boost PUFA metabolism – your body also needs sulfur to encourage growth and to repair tendons, joints, ligaments, and other connective tissues.

In fact, bathing in sulfrous water has been shown to improve osteoarthritis symptoms.[54,55]

A 2012 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found that MSM supplements can also reduce osteoarthritis symptoms.[56] While the MSM provided by SmartPrime-Om in Solace Joint Care isn't as much as those studies used, it goes to show how well-suited this ingredient is in a joint supplement. The MSM was really added to support the omega shift discussed above, but it just so happens to be a great joint ingredient as well!

SmartPrime-OM is a new omega-3 amplifying dietary supplement from Nutrashure, so we interviewed Dr. Hector Lopez to understand how it boosts EPA/DHA!

Summing up SmartPrime – powerfully anti-inflammatory

Chronic systemic inflammation of the type caused by excessive omega-6 PUFA activity is associated with the onset of arthritis,[57] and omega-3 supplementation has been shown to improve arthritis symptoms.[58]

When it comes to joint health, SmartPrime can potentially help decrease the burden of inflammation caused by omega-6 dominance. This is one of the most exciting ingredients of the decade -- if you want to learn more, read our article titled SmartPrime-Om: Tilting the Omega-3:Omega-6 Battle In Your Favor and watch our podcast on SmartPrime-Om with the late, great Dr. Hector Lopez.

-

Levagen + (90% Palmitoylethanolamide with LipiSperse) – 350 mg

Levagen is a powerful palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) ingredient that uses LipiSperse as a delivery mechanism.

Palmitoylethanolamide research

So what is PEA? It's a lipid compound with documented anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antimicrobial, immunomodulatory, and neuroprotective effects.[59]

The human body naturally produces some PEA endogenously, synthesizing it from palmitic acid, a type of fat found mainly in meat and dairy products.[60] However, your body only produces as much PEA as it needs at any given time. This means that many, if not most, of us might stand to benefit from PEA supplementation, which can potentially provide benefits above and beyond what we'd get from the minimum level of endogenously produced PEA.

Obviously vegans, vegetarians, and anyone else who minimizes their intake of animal products are more likely to benefit the most from taking exogenous PEA.

Today there are over 350 papers indexed in PubMed discussing PEA's wide range of benefits for human health, and PEA has actually been used around the world under a variety of brand names. Just to give a few examples, PEA has been used in the treatment of influenza and the common cold,[60] and has been proposed as a potential therapy for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).[61] It's also been studied for autoimmune and neurological diseases.[60,62,63]

PEA's ability to decrease inflammation is part of what makes it useful in all of these cases.

According to a meta-analysis published in the Journal of Pain Research, PEA is effective for the management of chronic and neuropathic pain in multiple animal models and in humans.[62]

Another research review published in the same journal found that PEA supplementation is both safe and effective for the management of nerve compression syndromes like sciatica pain and carpal tunnel syndrome.[63]

How PEA works – anti-inflammatory endocannabinoids

It seems that PEA works by activating proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α), which ultimately downregulates inflammatory cytokine production.[62] However, PEA also shows activity in the endocannabinoid system.[62] Just to give you some real-world context for what this means, endocannabinoids seem to play a significant role in the famous "runner's high" euphoria that many of us feel after intense exercise.[64]

But perhaps most interestingly, the endocannabinoid system also shows promise when it comes to managing arthritis. In fact, one peer-reviewed study claims that endocannabinoid upregulation might even stop the progression of arthritis![65]

This is because endocannabinoids are profoundly anti-inflammatory.[62,64,65] PEA also seems to inhibit mast cell activity, which is a big deal since mast cells are a crucial part of your body's inflammatory process.[66]

Between that and its ability to manage pain, when it comes to choosing an ingredient for a joint care formula, PEA is a no-brainer.

What is LipiSperse?

Now onto the delivery system: LipiSperse is a crystalline molecular coating that acts as a hydrophilic envelope.

The idea behind coating something like PEA in LipiSperse is to prevent fat-soluble compounds from forming clumps in liquid. In a sense, LipiSperse is a highly sophisticated emulsifier. LipiSperse has been shown in peer-reviewed studies to improve the bioavailability of curcumin and PEA, both of which are naturally fat soluble.[59]

We've been excited about palmitoylethanolamide for a while, occasionally running it when needed - but LipiSperse in Levagen should increase the efficacy even more.

-

Curcuwin Ultra+ (Curcuma longa [root])(min 20% curcuminoids) – 250 mg

Meet Matt Karich, an engineer who's putting his talents to use in the dietary supplement industry, with refreshingly unique, third-party tested formulas. We discuss this and more in PricePlow Podcast #068.

If you've been in the supplement game for any length of time, you've no doubt heard of curcumin, a bright yellow-orange anti-inflammatory compound,[67] and one of several curcuminoid blends that occur naturally in turmeric root. Turmeric has been used for millennia to manage many different ailments.[68] Generally speaking, its beneficial effects seem to be largely on account of its curcuminoids.

Although curcuminoid research is generally focused on curcumin, it seems to be the case that all the curcuminoids have broadly similar anti-inflammatory effects.[69] Curcumin and the other curcuminoids work by decreasing the body's burden of oxidative stress,[70-76] which naturally results in bringing down associated inflammation.[77-82]

As a class, curcuminoids have been studied extensively for their potential in preventing and managing several diseases, as well as their ability to improve liver, cardiovascular system, and brain health.[83]

Turmeric, curcuminoids and inflammation

Curcuminoid compounds inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2),[84-87] an enzyme that governs pro-inflammatory prostaglandins synthesis.[88] COX-2 is also a primary target of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen.

It's not a huge surprise, then, that curcumin has been shown to significantly reduce chronic pain[89-102] and improve osteoarthritis symptoms.[89-102]

Why Solace has Curcuwin Ultra+

Most of us are well aware of curcumin's power. Our regular readers also likely know that curcumin unfortunately has poor bioavailability, but it can be improved through a few different strategies.

This is why Soul Performance Nutrition is using Curcuwin Ultra+, a highly-bioavailable curcumin that touts 144 times greater bioavailability and 40% faster absorption than standard curcumin.[103,104] It's been studied at this dose, too -- eight weeks of 250 milligrams led to reduced muscle soreness post-exercise.[105] Another solid, study-supported choice by Soul.

-

Hyaluronic Acid (as Sodium Hyaluronate) – 100 mg

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a lubricating substance that occurs naturally in joints, eyes, and connective tissue. It has an interesting chemical makeup that enables it to retain water molecules throughout the body - helpful in both skin and joint support applications (since this is where you'll find about 50% of all HA).[106]

There's a ton of research on using HA injections to manage osteoarthritis and other inflammatory joint disorders. But as it turns out, oral supplementation works too! According to a 2016 review of HA literature, taking it by mouth can significantly improve knee pain.[107]

On top of its lubricating effects, it seems that HA reduces inflammation by increasing production of an anti-inflammatory cytokine called interleukin-10.[108]

Dosage and Directions

Per the label, take 4 capsules daily (1 serving) with food and water. We sometimes split our supplements into AM/PM dosing, which can be done here, but it's best to do whatever keeps you compliant.

Note: 200% DV in Vitamin A

It's worth mentioning that the beta carotene and retinyl palmitate in Caraflame provide 200% of the daily recommended value of Vitamin A (1800 mcg RAE [retinol activity equivalents]). Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin, so there's no need to don't overdo it - your body can store and accumulate it.

Conclusion: A Novel Joint Support Supplement

We often see ingredients like MSM and hyaluronic acid in joint health supplements as they're somewhat "joint-specific" ingredients. But in our opinion, a joint-specific approach to ingredient selection falls somewhat flat when it comes to actually improving joint health.

Solace Joint Care is the first product we've seen in this category to aggressively target the underlying cause of joint problems: systemic inflammation. Solace understands that in many cases, joint disorders are a reflection of poor general health, and not necessarily caused by joint-specific dysfunction.

It's also the second product (and first joint supplement) we've covered that uses NutraShure's SmartPrime, one of our favorite ingredients ever since we wrote about it earlier this year. SmartPrime's effects on PUFA metabolism – an unbelievably important aspect of human health – make it a great choice for many different types of formula.

Overall, we think this product could really hit it out of the park. Congratulations to Matt Karich and Soul Performance Nutrition for coming up with such a great formula - if you're feeling inflamed, it's one to seriously consider.

Soul Performance Nutrition Solace Joint Care – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

[pricedplow_videos]

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)