It's no secret that the team at Morphogen Nutrition has stepped their game up tremendously in the past couple of years. Morphogen is one of the industry's rising stars, and that's thanks largely to the visionary direction of founder and CEO Ben Hartman, who's been a guest on The PricePlow Podcast not once but twice:

- Ben Hartman – The Rise of Morphogen Nutrition | Episode #033

- Morphogen Nutrition Rebrands! Ben Hartman #2 | PPP #063

Every formula Morphogen touches turns to gold, which is why today we're stoked to talk about Morphogen's latest nootropic entry:

COGNIGEN Neuro-Accelerator, From Morphogen

The first thing to note about COGNIGEN Neuro-Accelerator's formula is that it's a little light on caffeine - just 100 milligrams of extended-release. This means you can stack it with your existing morning coffee, and can still take a fat burner, pre-workout, or energy drink in the same timeframe.

Instead, caffeine's cousin and fellow alkaloid theacrine is doing a lot of the stimulant lifting... but you just have to feel the effects of this nGin ginseng extract! Overall, COGNIGEN offers a substantially different stimulant experience than the typical nootropic formula fare, and we'll get into what makes theacrine special.

With ingredients like RhodioPrime rhodiola, the aforementioned nGin ginseng, and tyrosine, this formula heavily emphasizes stress resistance, which makes perfect sense to us. Typically, people reach for nootropic supplements to help them tolerate stressful situations, and the industry has really picked up on this and responded with appropriate ingredient selection.

With school starting up again, for instance, students could use a product like COGNIGEN to help prepare for exams, or even just a heavy daily workload.

But the real headline is Morphogen's use of D-serine, an amino acid that, despite playing a critical role in healthy cognition, is not an ingredient we've seen used very often.

Let's get into how this works, but first, check the Morphogen PricePlow news and deals:

Morphogen Nutrition COGNIGEN – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Before digging into the ingredients, make sure you see the following clip from our discussion in episode #102 of the PricePlow Podcast with the SportLife Distribution sales team, where Morphogen's formulation prowess is called out, and both sides agree to how well COGNIGEN works:

With that said, let's get into why everyone's loving it so much:

Morphogen COGNIGEN Ingredients

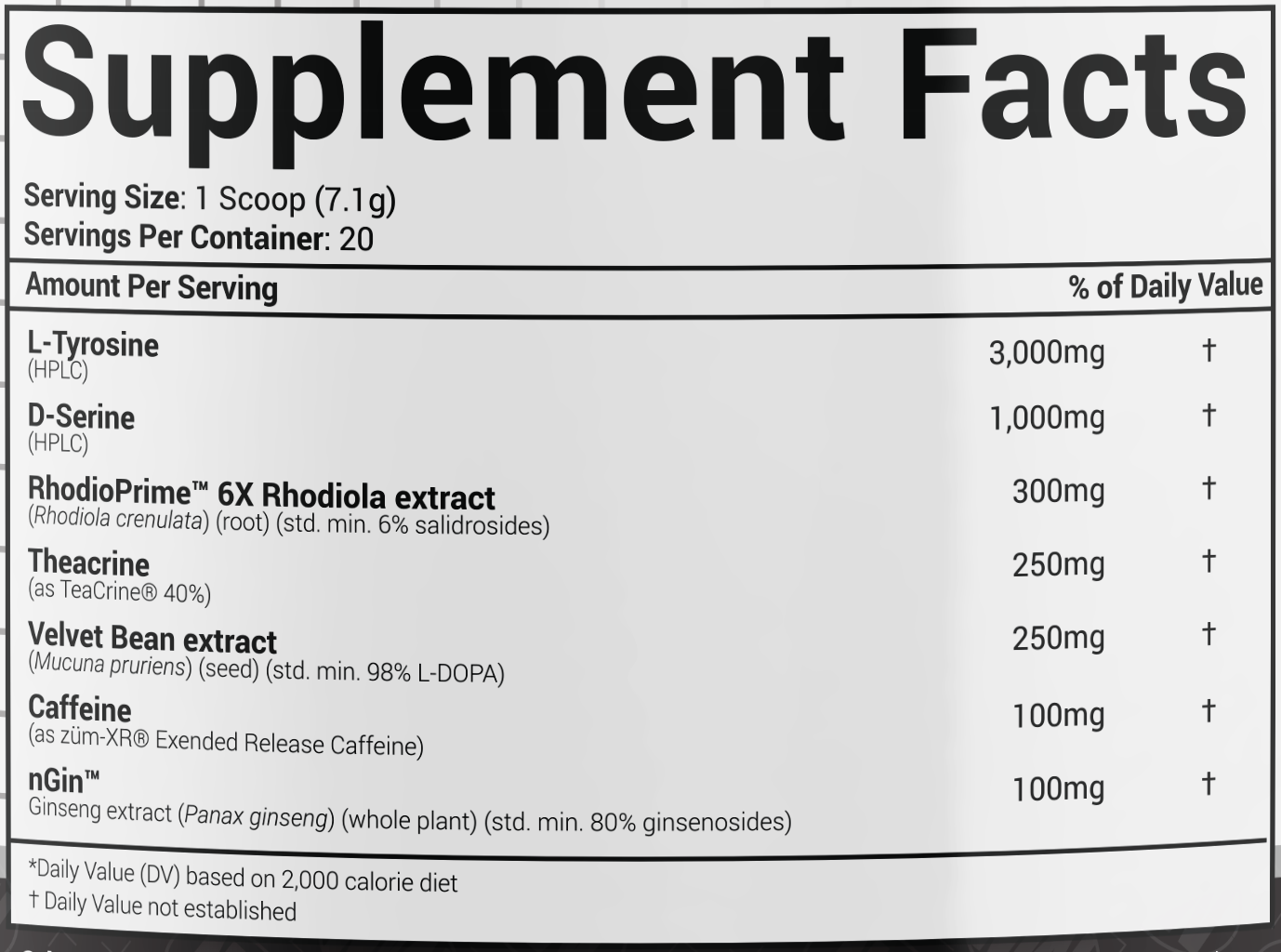

In a single 1-scoop serving (7.1 gram) of COGNIGEN from Morphogen, you get the following:

-

L-Tyrosine (HPLC) – 3,000 mg

Tyrosine is a crucial precursor to catecholamine neurotransmitters like dopamine, adrenaline, and noradrenaline, which are essential for maintaining focus, motivation, and energy levels.[1-3] Supporting the production of these neurotransmitters through tyrosine supplementation can help cognitive function during stressful situations.

Military forces worldwide have investigated tyrosine's ability to mitigate stress and enhance wakefulness. Notably, studies conducted by the U.S. military have revealed that tyrosine surpasses caffeine in improving alertness among sleep-deprived soldiers.[4,5]

Furthermore, tyrosine serves as a precursor to thyroid hormones like triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4). These hormones are vital for regulating metabolism, and the body requires an ample supply of tyrosine to produce them effectively.[6,7] Considering that many PricePlow readers are physically active and health-conscious, it's important to note that intense exercise and caloric restriction can have a negative impact on thyroid function.[8-10] Therefore, incorporating a small amount of tyrosine supplementation into your routine can potentially help maintain hormonal balance and support overall health in such scenarios.

-

D-Serine (HPLC) – (1,000 mg)

Serine is an amino acid that plays a key role in activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR).

The NMDAR is abundant in the brain's frontal cortex,[11] where it plays an important role in facilitating executive function (EF). In order to enable EF, the NMDAR must be activated by the presence of glutamate as well as one of the two NMDAR co-activators, which are serine and the amino acid glycine.[12]

As blood levels of glycine and serine decline with age,[13] so too does EF.[14] Of all cognitive abilities, EF impairment is most strongly correlated with mortality and functional decline.[15] This means that maintaining EF is a logical strategy for preserving aging populations' ability to function. It also means that past a certain age, most, if not all of us, could benefit from serine supplementation.

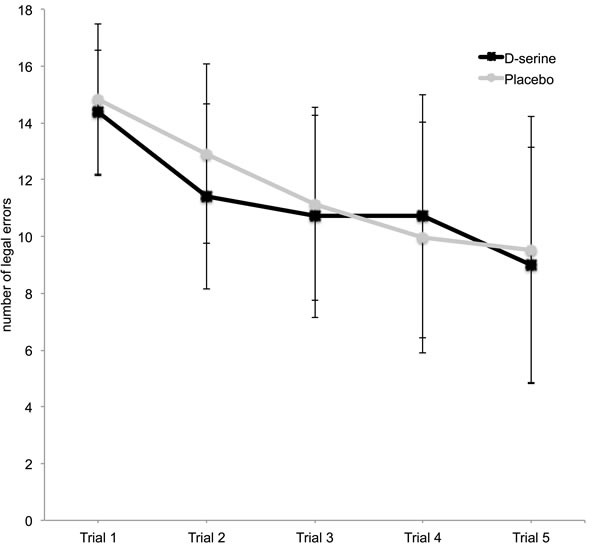

Older adults made significantly fewer errors on the Groton Maze Learning Test, (GMLT), a computerized test of executive function.[16]

One randomized, double-blind, crossover study from 2016 found that a single 30-mg/kg dose of D-serine was associated with significant improvements in executive function, spatial memory, learning, and problem solving in adults aged 65 and older.[16] Of course, the dose used in COGNIGEN isn't that high. Unless you weigh 33 kilograms (72 pounds), you'll get less than 30 mg/kg per serving. However, we don't see any reason for not double-scooping COGNIGEN. So, if you really want to get close to the clinical dose, you could do that.

It appears that not just older adults can benefit from D-serine supplementation. A randomized, double-blind, crossover study from 2015 found that after a single dose of D-serine, men and women aged 23-29 showed small but significant improvements in :[17]

- Anxiety

- Attention

- Working memory

- Well-being

Single vs. long-term doses

The 2015 study mentioned above used a 2.1-gram dose, which is about twice as much as the amount in a single serving of COGNIGEN. However, the study authors point out that the single-dose paradigm used in both studies is actually a limitation.[17] We haven't seen any long-term human studies on D-serine yet, but there's good reason to that taking 1,000 mg/day for several days is actually better than taking 2.1 grams or 30 mg/kg once.

Serine-ketamine connection

You've probably heard about how ketamine is the new breakthrough treatment for depression.[18] Now, since serine is an NMDAR agonist and ketamine is an NMDAR antagonist, you might think they would have opposite effects. Believe it or not, high-dose D-serine has been shown in animal models to have identical effects as the low-dose ketamine used in depression treatment.[19]

The basic reason for this is that serine and ketamine both have biphasic effects. Even though ketamine is an NMDAR antagonist, administering ketamine in low doses can cause an adaptive upregulation of the NDMAR. Similarly, high-dose serine can cause an adaptive downregulation of the NMDAR.[19]

In other words, there seems to be an overlap between the biphasic dosing schedules of D-serine and ketamine, which means they can have qualitatively similar effects on brain chemistry and, hence, mood.

-

RhodioPrime 6 Rhodiola extract (Rhodiola crenulata) (root) (std. min. 6% salidrosides) – 300 mg

There are species of Rhodiola commonly used for supplement formulation: Rhodiola rosea and Rhodiola crenulata. While closely related, these two plants differ in one important way.

Rhodiola rosea's primary bioactive constituents are rosavins, while crenulata contains more salidrosides. Although rosea is more commonly used than crenulata, there is compelling evidence suggesting that salidroside may exhibit superior efficacy in specific aspects of Rhodiola's effectiveness.[20,21]

Hence, based on the existing research literature, it's advisable to take Rhodiola extracts derived from the crenulata plant due to its significantly higher salidroside concentration.[22,23]

This is why Morphogen opts for NNB Nutrition's trademarked RhodioPrime extract, sourced from crenulata. RhodoPrime is the most potent extract on the market with an impressive 6% salidroside standardization, whereas most commercially available extracts typically contain around 1% salidroside.

At 6% salidroside, NNB Nutrition's RhodioPrime is the best way to feel the serious power of this wonderful herb!

Salidroside: Mechanisms of Action

According to the research literature, salidroside's mechanisms of action encompass the following:

- Increased long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampus[23]

- Enhanced autophagy via the mTOR pathway[24]

- Improved oxygen utilization via hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)[25]

- Upregulation of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, histamine, and serotonin[26]

- Inhibition of the monoamine oxidase (MOA) enzyme responsible for neurotransmitter breakdown[27]

- Upregulation of neuropeptide Y[24]

Thanks to these effects, a Rhodiola extract rich in salidroside is a powerful adaptogenic substance, capable of effectively reducing overall stress levels.

Salidroside benefits

The positive outcomes associated with salidrosides include:

- Enhanced cognition[28]

- Reduced stress and anxiety levels[29]

- Improved mood[29]

- Alleviated symptoms of depression[30]

Furthermore, Rhodiola has demonstrated its ability to combat both physical and mental fatigue,[31,32] enhance athletic performance,[33] regulate appetite,[34] and improve glucose metabolism.[35]

-

Theacrine (as TeaCrine 40%) – 250 mg

Theacrine is a compound closely related to caffeine,[36] renowned for its potent stimulant properties. Like caffeine, theacrine is an alkaloid and occurs naturally in Camellia kucha, a traditional Chinese tea better known as kucha.[37]

Like caffeine, theacrine helps increase mental and physical energy by blocking the action of adenosine receptors[38] and inhibiting phosphodiesterase.[39]

It also upregulates dopamine,[40] a neurotransmitter that is absolutely crucial for focus, motivation, and mental energy.

One animal study found that theacrine use over time does not produce drug tolerance.[40] If replicated in humans, this should mean that repeated theacrine administration consistently gives the same effects as the first dose, no matter how many times you take it!

One study found that theacrine can increase time to exhaustion at 85% VO2max by 27-38%[41] – while not strictly speaking a nootropic effect, we think this is still worth mentioning because it's a huge effect size and increased exercise tolerance is definitely beneficial if you use exercise to manage stress and improve cognition.

Finally, since most of us take nootropic supplements to deal with stressful situations, it's interesting to note that an animal study found theacrine administration can prevent stress-induced liver damage.[37]

-

Velvet Bean extract (Mucuna pruriens) (seed) (std. min. 98% L-DOPA) – 250 mg

Mucuna pruriens, commonly known as velvet bean, is rich in powerful antioxidants and is known for its ability to upregulate dopamine.[42] Extracts of Mucuna are typically standardized for an amino acid called L-DOPA,[43] which is a direct precursor to dopamine.[44]

Beyond its dopamine-boosting properties, L-DOPA (also known as levodopa) is a formidable anti-stress compound with a documented ability to reduce cortisol levels.[45-47] This quality makes L-DOPA an excellent complement to stimulants like theacrine (which is also in Morphogen COGNIGEN), as it can take the edge off of stimulant effects.

Reducing cortisol levels is generally a good thing for anyone under mental or physical duress, as cortisol rises during stress[48] and can lead to a decline in testosterone levels.[49,50]

Regarding muscle growth, both Mucuna and L-DOPA have demonstrated the ability to stimulate the body's production of growth hormone (GH),[51-53] another crucial hormone for promoting anabolic processes. Again, stress can promote catabolic processes,[54] so helping support muscle preservation and growth should be considered an important anti-stress effect.

Furthermore, L-DOPA can assist in regulating prolactin levels,[55] a beneficial feature for a pre-workout formula as prolactin levels also tend to rise during stress.[56]

-

Caffeine (as zum XR extended Release Caffeine) – 100 mg

Caffeine, a methylxanthine stimulant, ranks as one of the most extensively researched substances in existence. It possesses a rare but important characteristic among dietary supplements – namely, its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

In the brain, caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors. Adenosine, a nucleotide, induces feelings of fatigue as it accumulates. Consequently, inhibiting its action at the receptor level, through caffeine supplementation, is an effective strategy for combating fatigue.[57]

Caffeine also inhibits phosphodiesterase, an enzyme responsible for degrading cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).[57] By elevating cAMP levels through phosphodiesterase inhibition, caffeine has the capacity to enhance cellular activity, an effect that applies to neurons as much as any other cell in the body.[58,59]

Caffeine not only protects dopaminergic neurons against potential harm (one reason for its association with a reduced risk of Parkinson's), but also enhances dopaminergic signaling in healthy individuals.[60,61] This enhancement contributes to heightened focus and motivation.

Research on caffeine demonstrates its ability to:

- Reduce reaction times[62]

- Enhance attention[62,63]

- Heighten alertness[63]

- Sustain physical and cognitive capabilities in stressful situations[63]

- Improve working memory[64]

Benefits of zum XR extended release caffeine

MorphoGen opted for a time-released or extended-release form of caffeine called zum XR. Because it's absorbed into the bloodstream more gradually than ordinary caffeine anhydrous, zum XR can smooth out your caffeine energy curve, helping you avoid rapid energy increases or rapid energy crashes.

-

nGin Ginseng extract (Panax ginseng) (whole plant) (std. min. 80% ginsenosides) – 100 mg

Ginseng, scientifically known as Panax ginseng, possesses well-documented capabilities to fight fatigue and alleviate symptoms associated with stress-related depression and anxiety.[65]

One of ginseng's most intriguing benefits lies in its ability to reduce apoptosis, which is the programmed cell death that occurs during periods of intense stress.[66] This mechanism is believed to be achieved through ginseng's attenuation of the body's inflammatory response to stress, and is facilitated by the potent ginsenoside antioxidant phytochemicals present in ginseng.[65]

Regarding its nootropic effects, ginseng has been shown to improve various aspects of cognition, including reaction times, working memory, arithmetic skills, and cognitive flexibility.[67-69]

Researchers have also identified ginseng's "glucoregulatory" properties, indicating its capacity to maintain healthy glucose metabolism under stressful conditions. This is yet another way ginseng can help prevent or reduce the decline in cognitive performance associated with stress.[70]

Stack Cognigen with the new Alphagen for an ultimate cognitive pre-workout mix!

Flavors Available

Conclusion

As you can see, Morphogen Nutrition COGNIGEN is an awesome formula to use if you're under a lot of pressure. We especially appreciate the fact that Morphogen opted for RhodioPrime. Rhodiola crenulata appears to be simply better than Rhodiola rosea, and we're hoping the industry as a whole follows Morphogen's lead in recognizing that rosea extracts are obsolete.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)