Most of us – hopefully – have experienced the runner's high that comes from a great workout. It's this healthy, euphoric feeling that motivates gym goers the world over to hit it hard day after day after day.

It's tempting to write this sensation off as a spiritual experience, in that it's a transient and fleeting spike in happiness. But, as it turns out, runner's high may have benefits that go way beyond mental or emotional health.

Know the Runner’s High? Then you’ve activated the Endocannabinoid System

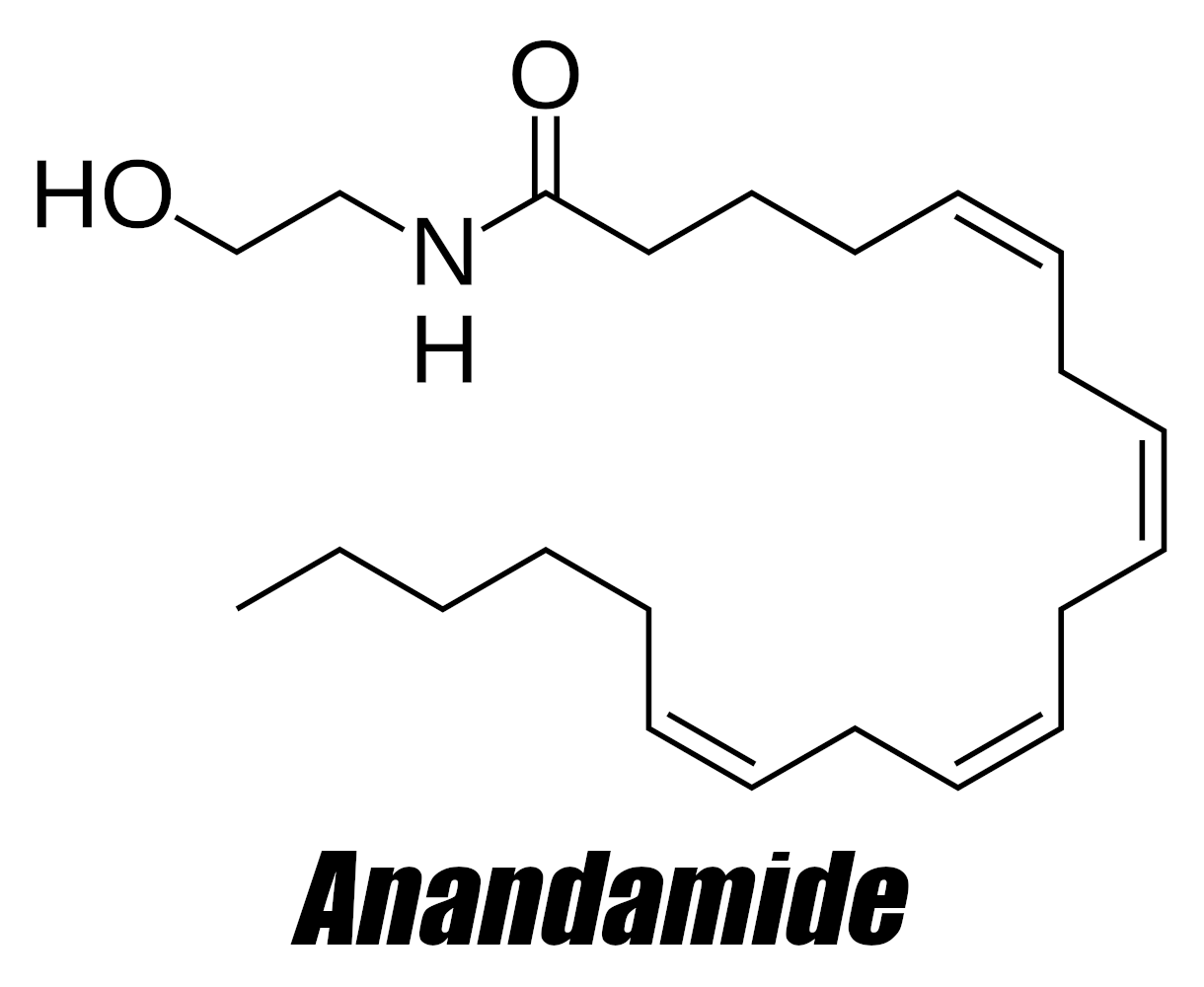

Anandamide (AEA) is the first-discovered endocannabinoid, named after the Sanskrit word "bliss". It's produced in the body and supplementing more can lead to improved mood, sleep, pain tolerance, vasodilation, and increased appetite.

Mounting scientific evidence indicates that the activation of the brain's endocannabinoid system, which plays a central role in mediating runner's high,[1] can help improve mood, as well as pain tolerance, sleep quality, cognitive performance, appetite regulation, and circulatory health.

That's what inspired novel ingredient developer NNB Nutrition to create FastBliss, their trademarked form of anandamide (AEA), which is one of the body's principal endocannabinoid molecules.

Cannabinoids of all types tend to get a bad rap because of their presence in certain recreational drugs, and potential for abuse. But endocannabinoids, being produced by the body endogenously, are subject to our internal feedback mechanisms that can make their use less problematic.

Nonetheless, cannabidiol (CBD) has gained widespread acceptance as a relatively safe exogenous cannabinoid.[2] Anyone who's familiar with CBD's benefits may be intrigued to learn that AEA is basically the body's endogenous version of CBD.

Meet Anandamide and FastBliss: A supplemental endocannabinoid

Although supplemental cannabinoids are common, and we've written about plenty of supplement ingredients that activate endocannabinoid receptors, we rarely, if ever, see supplemental endocannabinoids.

NNB Nutrition's FastBliss is a stable, tested, standardized form of anandamide that comes in both oil and powder form. NNB is a sponsor of PricePlow.

Because of this, when it comes to supplemental AEA, there's not much human research, so in this article, we'll discuss a lot of theory and FastBliss' potential benefits.

Fortunately, there are numerous high quality animal studies that look at ways anandamide helps manage sleep quality, pain, immunity, and more. But as we all know, animal studies aren't perfect, so let's agree to take the results with a grain of salt.

Let's get into it, but first, make sure you're signed up for PricePlow's news and deal alerts for NNB Nutrition, anandamide, and FastBliss:

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

What is Anandamide?

Anandamide, also known as arachidonylethanolamide and AEA, is an endogenous lipid molecule that binds to the cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors.[3,4] Discovered in 1992,[5] it immediately received a great deal of attention and research in the early 2000s through today - especially in terms of cardiovascular, immune, gastrointestinal, and nervous systems.

The researchers who discovered anandamide named it after the Sanskrit word "ananda", which means bliss.[5] Ensuing research covered below in this article showed that this was an appropriate name to give the molecule.

A major discovery: the first of the endocannabinoids

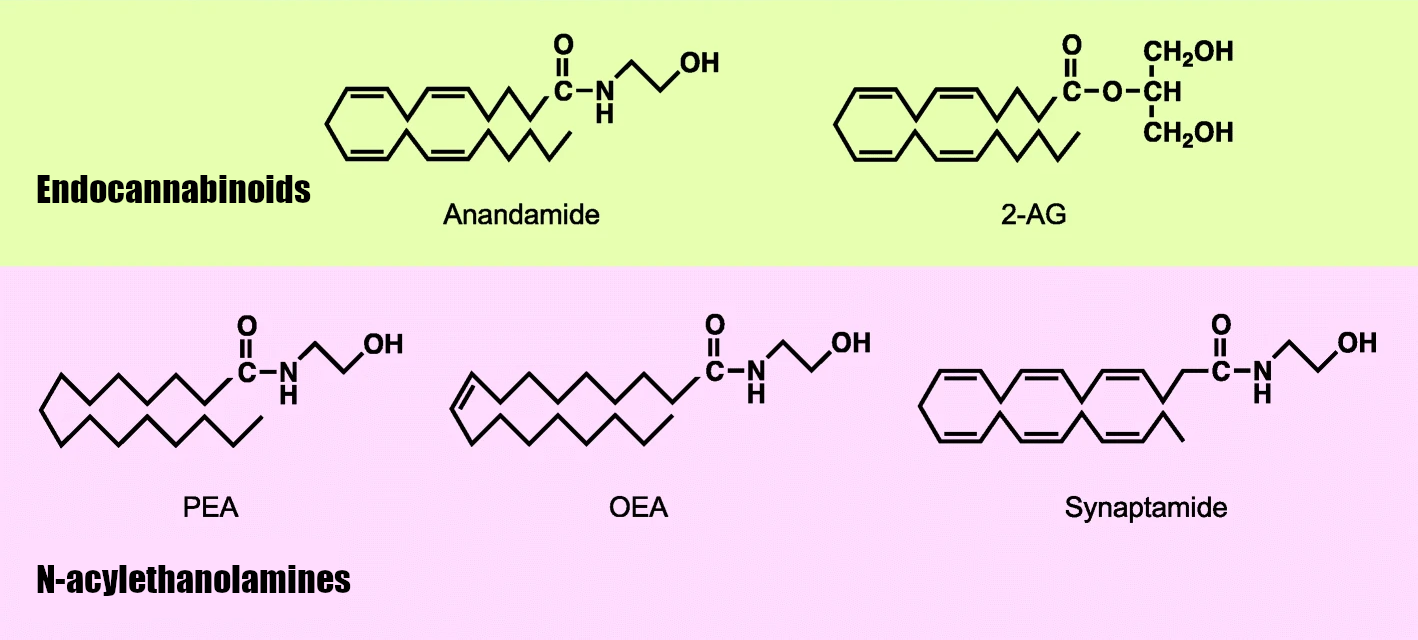

Alongside the discovery of its "chemical twin brother" 2-AG (2-arachidonoylglycerol) in 1995,[6,7] it soon became widely accepted that the mammalian nervous system possessed its own endocannabinoid molecules (like AEA and 2-AG) that resemble THC, the main bioactive compound of Cannabis plants.[8]

Why does the body produce anandamide and other endocannabinoids?

Anandamide is a lipid molecule generated in the body in varying amounts based upon the situation. As alluded to in the intro, it's released during exercise in humans and rats with both strenuous cardio and resistance training,[9-18] leading to exercise-induced hypoalgesia (decreased sensitivity to pain after exercise). Subjects experiencing painful diseases like fibromyalgia also have higher AEA levels than healthy controls.[19,20]

Both of the above indicate that it's a type of internal pain transmission controller the body produces anandamide, alongside 2-AG and other related compounds like OEA (oleoylethanolamide), PEA (palmitoylethanolamide), and SEA (stearoylethanolamide).[9,15] These molecules together constitute what's known as the "endocannabinoidome" - but realize that AEA and 2-AG are the actual endocannabinoids that bind to the cannabinoid receptors, while OEA, PEA, and SEA are N-acylethanolamines that exert anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects via different receptors.[21]

Anandamide (AEA) and 2-AG are the two endocannabinoids, with related N-acylethanolamines exerting activity too.[21]

AEA likely contributes to much more than that, though. For instance, there's research indicating that the body may use it to combat high blood pressure.[22] And the endocannabinoidome has more recently been researched for its role in metabolism[23-25] and gut health[26-28] alongside neuropsychiatry.[29,30] This all presents an excellent opportunity for supplementation.

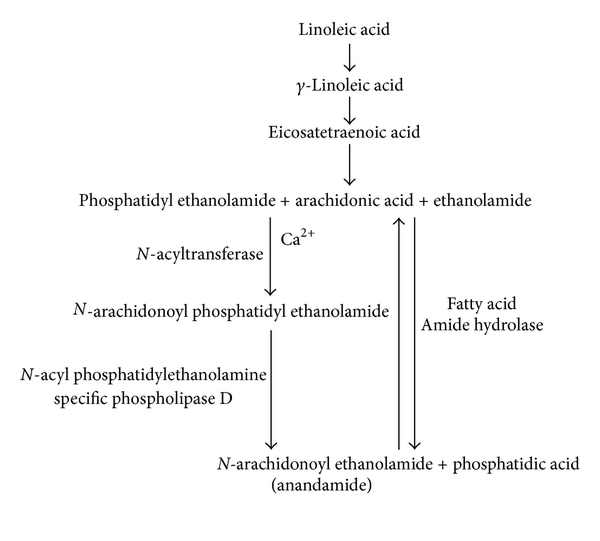

How is the anandamide produced?

From the biochemical viewpoint, anandamide is derived from arachidonic acid (AA), which is conjugated with ethanolamide.[31] It's also structurally related to capsaicin,[32] the well-known active biological component of spicy peppers. Baseline levels of AEA are regulated by the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH),[33] a family of hydrolyzing enzymes.

Activation of the vanilloid TRPV1 receptor stimulates the synthesis and release of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide.[34] This is also the same receptor that capsaicin activates.[35]

However, it's not just endogenously produced:

Anandamide found in nature: Cocoa and truffles

Anandamide can be found in cocoa[36-38] as well as truffles (the fruiting body of fungi).[39]

Interestingly, cocoa also contains compounds that inhibit AEA breakdown,[37] which may add to its well-known blissful sensation. It's also worth noting that CBD inhibits anandamide's breakdown, enhancing its signaling.[40]

Research is ongoing - this article covers much of what's currently known on a greater surface level - in terms of the compound's effects when used as an exogenous ingredient. However, the references cited above and below contain deeper-level citations expanding on the biochemistry of this fascinating molecule (and on the endocannabinoid system in general), both of which are not covered as intensely. Let's take a closer look:

Anandamide research through February 2023

Below we've broken the article down into various sections. You can also see the table of contents to the right.

-

Analgesic and Anti-Depressant Effects

Nearly immediately after its discovery in 1992, a research team published a paper in 1993 showing that anandamide has analgesic effects in mice.[41] Researchers would soon discover AEA's involvement in the body's own pain control systems, along with its ability to increase pain tolerance during and after exercise.

The famous runner's high probably exists, at least, in part, to help us deal with the pain of physical exertion. Thinking in evolutionary terms, survival often depends on a willingness to move fast, and potentially for long periods of time.

Endocannabinoids can help us do this since the entire endocannabinoid system is involved in pain modulation and has broadly analgesic (pain suppressing) effects.[42]

More specifically, AEA is released during exercise[9-18] and contributes to the relaxing (or even sedative) effects of a good workout, in addition to the known hypoalgesic effect of exercise (reduced pain sensitivity).

AEA can also improve symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD).[43] Although MDD is traditionally thought of as a psychological disorder, depressive symptoms and physical pain share important underlying mechanisms[44] that, potentially, can be modulated by endocannabinoids like AEA.

-

Reversed depressive behavior in diabetic rats (2016)

In a 2016 study, rats were given diabetes with a streptozotocin injection and then subjected to a forced swimming test,[45] which is one way that researchers model depressive behavior in animals. That test is exactly what its name seems to imply: the animals are dropped into a tank of water, from which they cannot escape, literally forcing them to swim.

Animals that exhibit passive behavior — they basically give up — are considered depressed. But the animals that have an active response to their circumstances — they swim for longer periods of time or try to escape — are considered to be less depressed.

Diabetic rats typically exhibit more depressive behavior than healthy rats. So the study authors were curious to see whether modulating the endocannabinoid system would help restore their behavior to baseline.

The researchers discovered that when the rats were given anandamide, they exhibited less depressive behaviors and were more active in their response to the forced swimming[45] – confirming that AEA can reverse depressive changes that typically go along with diabetes-induced metabolic dysfunction.

Mechanism of action: Serotonin, glutathione, and superoxide dismutase restoration

It seems that anandamide did this partly by restoring serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine / 5-HT) levels in the rats' brains. Since serotonin is a critical neurotransmitter we often call the "happy hormone", it suggests that AEA can help restore neurotransmitter production in depressive animals.

Perhaps most intriguing is the finding that the AEA helped restore glutathione (GSH) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) production in the diabetic rats – yet another data point for the theory that chronic inflammation and oxidative stress contribute to depressive symptoms.[45]

-

AEA upregulation blunted pain response in rats (2010)

In another study, this one from 2010,[46] researchers gave rats a drug called URB937, which inhibits AEA breakdown in peripheral tissues. It effectively increased the amount of anandamide present in the rats' extremities. The researchers then measured their response to pain.

They found that when given URB937, the rats showed a markedly less intense response to pain -- both visceral pain (pain in and around the internal organs) and nerve pain.[46]

Animal studies aren't perfect, but taken as a whole, they provide compelling evidence that exogenous AEA supplementation may help manage both mental and physical pain.

-

Brain levels of AEA predict anxious behavior in mice (2014)

In a study from 2014, researchers subjected mice to foot shocks, which induces stress in animals. The researchers then put them into a box with a light region and a dark region, known as a light-dark box.[47]

Animals that are anxious tend to prefer spending time in the dark region – animals with less anxiety prefer hanging out in the light.

One group of rats was given PF-3845, a drug similar to URB937 in that it inhibits the enzyme responsible for degrading anandamide. Again, this is a way of raising anandamide levels. The control group of rats got an inert placebo. Both groups were then subjected to the stress and placed in the light-dark box.

What the researchers found was that the mice in the high AEA group who received PF-3845 spent significantly more time in the light compared to the mice that got the placebo.[47]

The PF-3845 group also ate more and traveled a great distance inside the box – both of which are signs of low anxiety.

The researchers directly measured AEA levels in the mice's brains, making this study the first peer-reviewed evidence that low brain AEA levels predict anxious behavior.[47]

-

-

Sleep Quality

If you've done any reading on human health, then you know that sleep is crucial to long-term performance and wellness.

So we'll start by talking about anandamide's (and the other endocannabinoids) ability to improve sleep quality. Arguably, this is the point of maximum leverage when it comes to improving personal health.

-

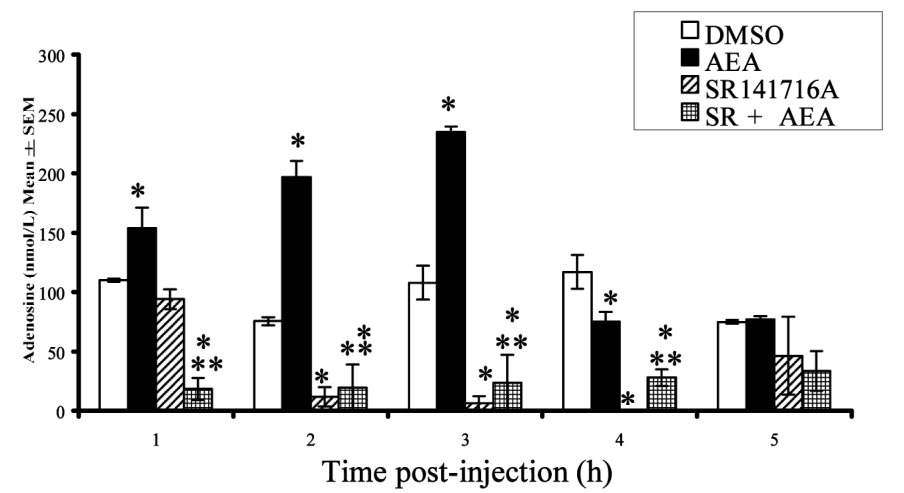

2003 Rat Study: Anandamide Upregulates Adenosine (anti-caffeine effects)

Regular readers of the PricePlow Blog know that adenosine buildup is a major factor in fatigue and sleep onset. We write about it at least once a week, thanks to the large number of supplements in which the adenosine antagonist, caffeine, is a primary ingredient.

Interestingly, just as caffeine promotes wakefulness by inhibiting the action of adenosine, anandamide has been shown to promote sleep onset by upregulating adenosine![48]

A 2003 study in rats showed this using a sophisticated and ingenious method. The researchers actually implanted the rats with neural probes that monitored their brain activity during sleep and collected and analyzed samples of brain fluid to establish a baseline for adenosine levels. They then injected the rats with AEA and monitored the samples for changes in adenosine.[48]

1-3 hours after anandamide (AEA) administration, the rats had significantly higher adenosine levels compared to baseline[48]

In the study, the rats also served as the placebo control. The researchers first injected them with DMSO, a solvent with no neurological effects, followed by AEA the next day. Using the rats' response to the DMSO as the baseline, the researchers compared it to the rats' response to AEA.

They found after the AEA injection, the rats had significantly higher levels of adenosine compared to DMSO. Their adenosine concentrations peaked hour three.

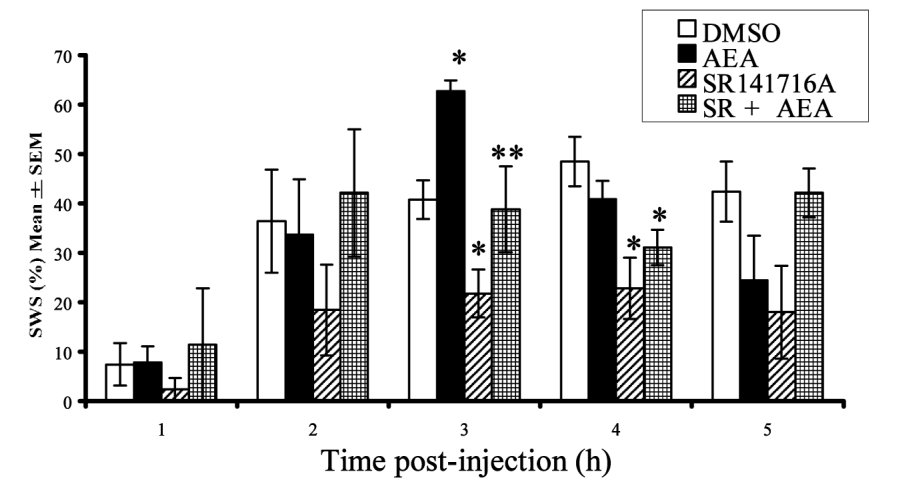

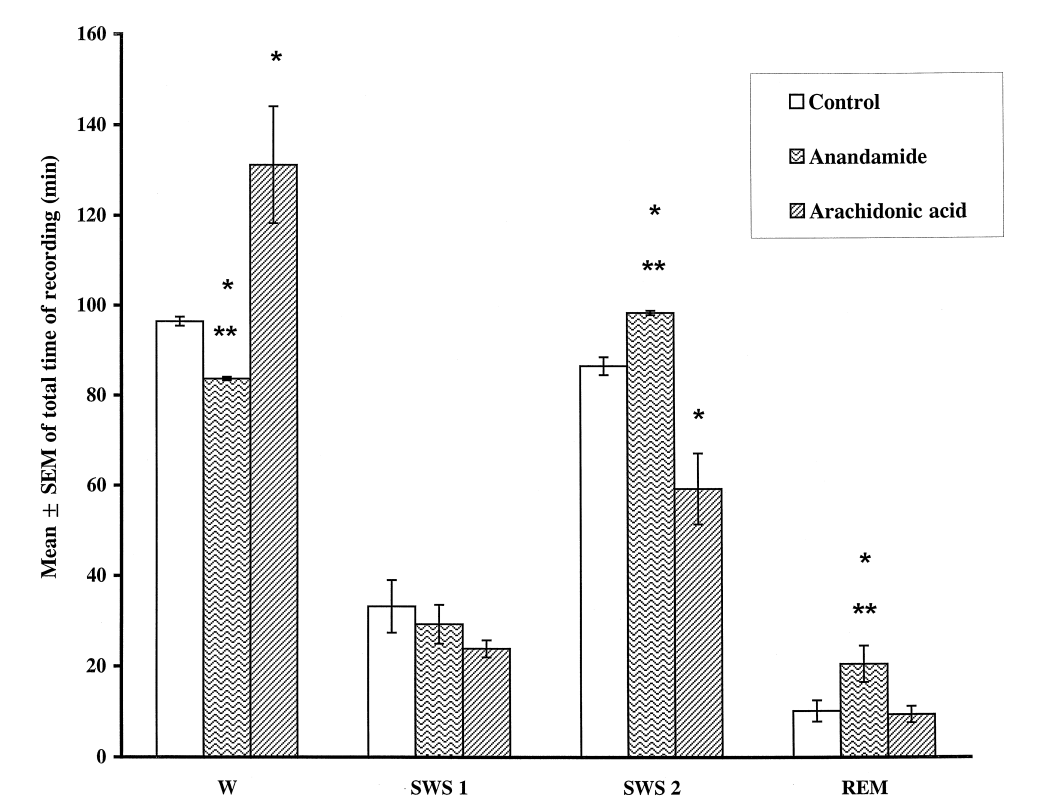

When given anandamide (AEA), the rats spent significantly less time awake and more time in slow-wave sleep (SWS).[48]

It was also during hour three that the rats spent the most time in slow-wave sleep (SWS), which refers to a pattern of brain activity that signifies the most restorative stage of sleep.[49] Compared to the DMSO, they experienced 54.5% more SWS after getting anandamide.[48]

The rats also spent less time awake,[48] which is obviously the goal when you're trying to get more sleep:

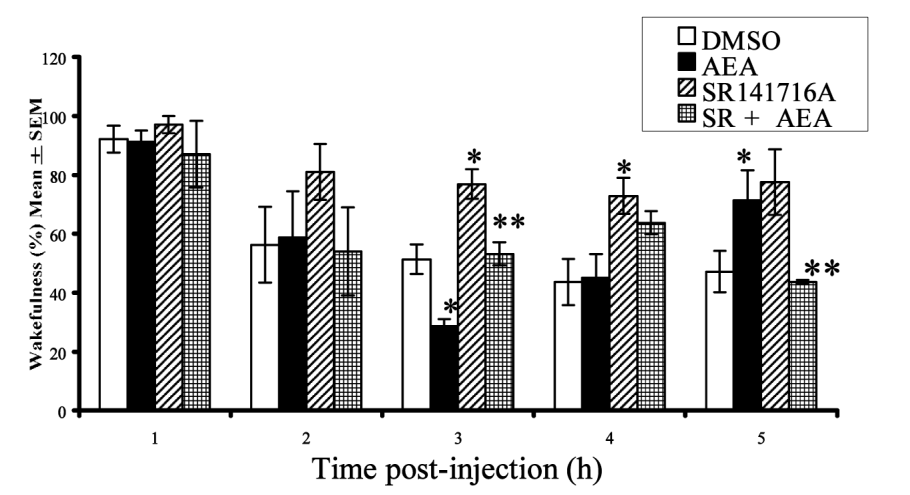

Rats were least awake 3 hours after anandamide (AEA) was given.[48] This could have major implications in sleep supplementation.

Anandamide mechanism of action: cannabinoid receptor type 1

Another thing the researchers set out to do was identify the specific receptor responsible for anandamide's effect. So next, they injected the rats with SR141716A, a cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) antagonist. The idea was that if antagonizing the CB1 receptor counteracted the effects of AEA, it would confirm that AEA was acting (at least in part) by activating the CB1 receptor.

That's exactly what they found – so it appears that the CB1 receptor is behind AEA's sleep benefits.[48]

-

1998 Rat Study: Anandamide and Slow-Wave Sleep

Another rat study, conducted a few years earlier in 1998, had already reached similar conclusions about AEA and sleep quality.[50] This study used a similar design as the one we just described:

First, the researchers attached electrode probes to the rats' brains to monitor their brain waves, then injected them with AEA and the precursor to AEA — arachidonic acid (AA). Next, the researchers analyzed brain wave data produced immediately after the treatments.

The results? The rats given AEA spent significantly less time awake and more time in slow-wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.[50]

A quick note about arachidonic acid and sleep

In contrast to AEA, arachidonic acid (AA) had the opposite effect – it promoted wakefulness at the expense of SES and REM.[50] AA is something we've written about on the PricePlow Blog many times. It's an ingredient with anabolic properties that's used in muscle-building supplements. But more importantly, it's a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) that's abundant in omega-6-dominant foods and processed oils.

We won't get too deep into the weeds on arachidonic acid -- that discussion is outside the scope of this article. But we do want to make a quick note of the fact that if you're eating foods high in AA – this is a category that includes the infamous seed oils like soybean oil, sunflower oil, safflower oil, and canola oil – you should consider the possibility that your high AA intake is contributing to any sleep problems you may have.

-

-

Anti-Inflammatory Effects: Combating the cytokine storm

If you've paid close attention to the news in recent years, you've no doubt heard of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), an inflammatory condition of the lung that's associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.[51]

ARDS is caused by what's called a cytokine storm – when the body over-produces large amounts of inflammatory cytokines, usually as part of the immune response, which is why it's associated with severe viral illness.

Due to the high burden of mortality and disability associated with ARDS, scientists spent a lot of time searching for substances that could attenuate (or perhaps even stop) it.

And as it turns out, AEA may be one of these substances.

Rescues Lung Function And Reduces Inflammation In Mice With ARDS (2021)

According to a 2021 study, anandamide can actually alter the expression of genes responsible for the inflammatory response that underlies ARDS.[52]

In this study, researchers induced ARDS in mice by applying a toxin called Staphylococcus Enterotoxin B, a profoundly inflammatory antigen produced by Staphylococcus aureus, the bacterium responsible for what's colloquially known as staph infections.

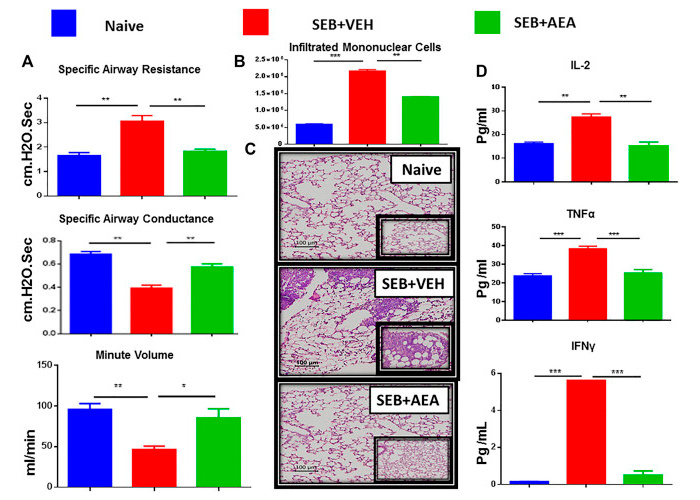

When mice were given SEB and AEA, they experienced significantly improved airway resistance, airway conductance, and respiratory volume per minute compared to mice that only got the SEB. In fact, the improvements seen with anandamide were so significant that the mice were considered almost as healthy as control mice that received no treatments.[52]

Look at this - Anandamide nearly completely rescues cells from the cytokine storm! Mice given anandamide (AEA) fared significantly better during induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) than those who got an inert vehicle as placebo control[52]

Moreover, the measured concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), were significantly lower in the ARDS mice who got AEA – again, about on par with what was observed in the control mice that received no treatment whatsoever.[52]

Pay close attention to the histopathological slides in the inset image from this study. Even for the layman, it's easy to see that inflammation in the SEB+VEH (VEH being the placebo) group is far worse than in either the naive (no treatment) group or the SEB+AEA group.[52]

So, in the data from this study, you can literally see the reduction in inflammation from AEA treatment. It was nearly a total rescue.

This leads us to believe that anandamide is an ingredient that should be considered in immunity supplements - something nobody seems to be using it for through 2013.

Restores Normal Social Behavior In Rats With Inflammation

It's well known that early life inflammation can have significant consequences for a mammal, including the development of social deficits or socially withdrawn behavior, thanks to the effect that inflammation has on the brain.[53,54]

It's also been observed that this post-inflammatory social behavior is characterized by an increase in fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme responsible for breaking down AEA, and a downregulation of cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1), the receptor primarily responsible for AEA's physiological effects.[53,55]

This is evidence that disrupted AEA signaling might be implicated in the social deficits caused by inflammation. So a team of researchers set out to see whether restoring AEA signaling could reverse these deficits, and bring back social behavior to baseline.

In their 2016 study, they first injected adolescent rats with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) toxins, which are known inflammatory agents. After getting the LPS injections and the resulting inflammation, the rats displayed the usual social deficits.[53]

The rats were then given a large dose of an FAAH inhibitor. Note that it was not FAAH itself, but rather, an inhibitor of it. This actually further increased the rats' AEA levels by reducing AEA breakdown.

What the researchers found was that the socially deficient rats who got the FAAH inhibitor started behaving normally. In their willingness to play and exhibit exploratory behavior, they resembled healthy control rats.[53]

There's still much to be explored here. It doesn't totally make sense that an inflammatory challenge would increase both AEA levels and FAAH levels, and the authors of the study were interested in that as well. If you're really curious to find out more about what's going on here, head to the study URL and read the paper's Discussion section, where the authors propose various explanations.[53]

-

Vasodilation effects of anandamide

A study published in 2004 showed that anandamide is able to cause vasodilation in dural vessels in a dose-dependent fashion by activating the vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptor.[56] Dural vessels are the blood vessels in the dura mater, the thick membrane made of connective tissue that surrounds the spinal cord and brain.

This could have implications for migraine sufferers, but more research is required.

Circulatory health support

Further anandamide research also shows vasodilation in abdominal vascular tissue[57] and in pulmonary arteries.[58] Finally, research shows that anandamide can significantly decrease blood pressure.[22] This all leads us to believe that its vasodilatory properties go beyond specific areas of the body, and it can support systemic vasodilation.

It seems that the body endogenously attempts to use anandamide as a blood pressure regulator: Patients with obstructive sleep apnea -- a known hypertensive disease -- have increased circulating endocannabinoid concentrations even compared to obese subjects.[59]

Postulated Mechanism: inhibited norepinephrine release

The researchers in the sleep apnea / hypertension study speculate what the mechanism could be here:

"In animal studies, peripheral endocannabinoid application lowered blood pressure and decreased norepinephrine concentrations, presumably by inhibiting norepinephrine release from presynaptic neurons.[60,61]

Following this line, the peripheral endocannabinoid system may serve as a compensatory mechanism attenuating a further blood pressure increase in the setting of sleep apnea, but maybe also in other forms of hypertension. The latter hypothesis is supported by experiments in hypertensive animals."[59]

Again, more research is to be determined, but this could have a potential role in a unique, blissful pre-workout vasodilation effect that's worth exploring by cutting edge companies. Oftentimes, we see ingredients like this as useful agents to "take the edge off" of the stimulants. As we'll see in some preclinical data below provided by NNB Nutrition, FastBliss anandamide seems to be highly synergistic with exercise, so this is an avenue well worth exploring.

-

Appetite stimulation from anandamide

It should come as no surprise to anyone who has studied endocannabinoids or cannabinoids in general that anandamide is an appetite stimulant. It's well-known through their actions on the brain's CB1 receptors, endocannabinoids stimulate appetite and consumptive behavior.[62]

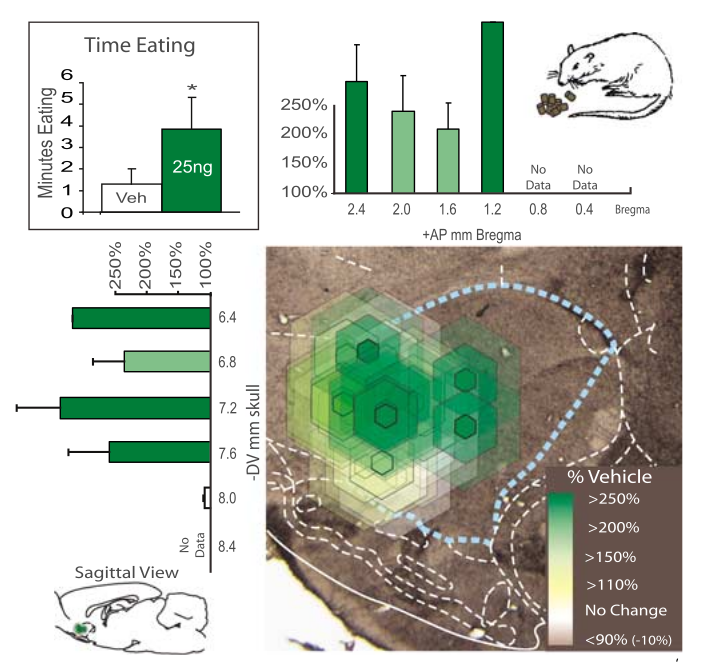

A study published in 2000 showed that a very low dose of AEA (0.001 mg/kg) in mice led to 44% more food consumed.[63] This was a one-week study where the mice ate for 2.5 hours each day.

A subsequent animal trial published in 2007 showed that anandamide doubled the number of eating bouts (203%) and produced a 600% increase in chow intake in rats![64]

These are impressive numbers -- especially in the low-dose study[63] -- and could certainly be of assistance -- or detriment -- based upon one's goals! Regardless, the effect is well worth knowing.

Tolerating bitter flavors

Interestingly, the anandamide given in the 2007 study made the rats tolerate bitter compounds like quinine more.[64] This potentially opens the door to applications in flavor sensitivity and bitter masking.

Cons of Anandamide Supplementation

First, it should be clear that dieters who are attempting to lose weight should not take appetite stimulants, a category that anandamide (and other cannabinoids and endocannabinoids) fit in. This effect could, of course, also be taken as a benefit for those who are "hard gainers" or need additional appetite stimulation.

Anandamide seems convincingly effective for the above applications based on the research we've discussed so far. Unfortunately, nothing is perfect, and there is one circumstance under which we would not recommend using an AEA supplement.

In a nutshell, we recommend against taking AEA if you are in the process of learning something important, and especially if you need to retain that information long-term.

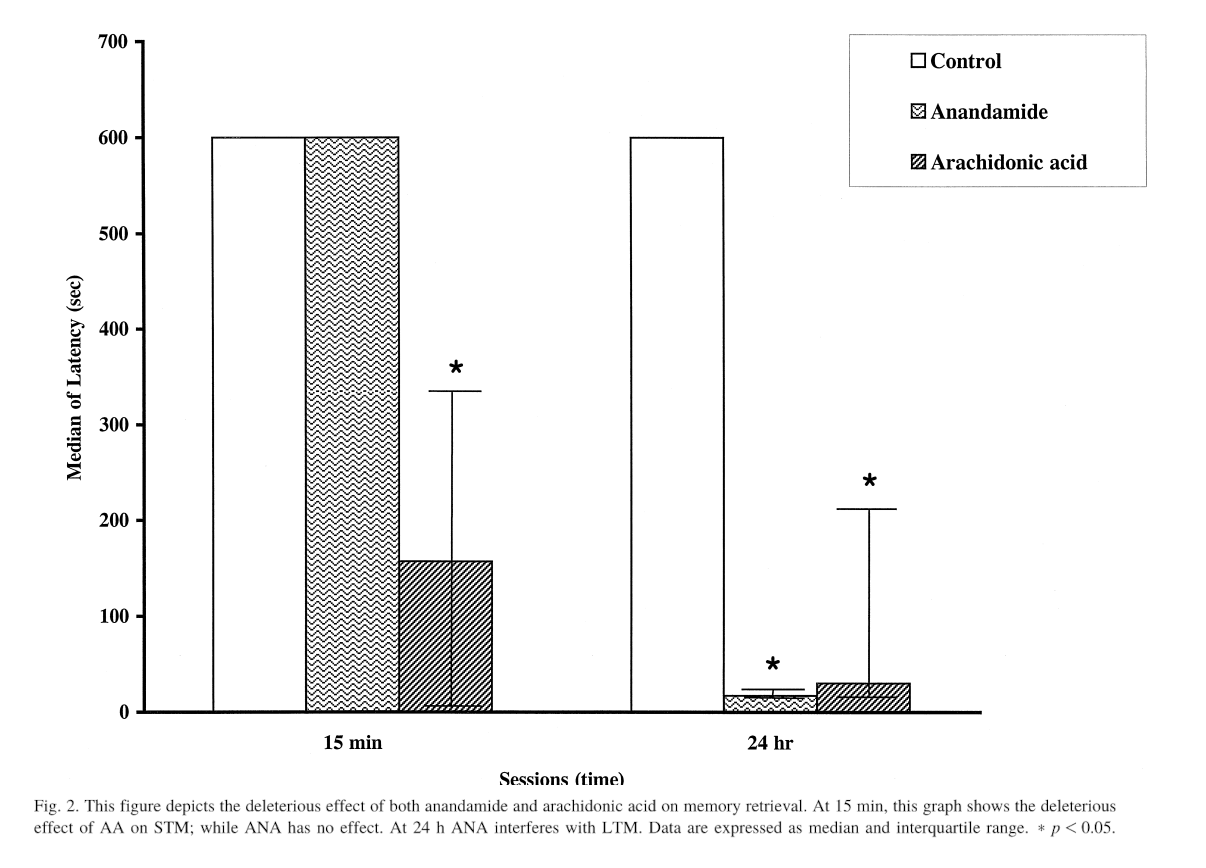

Our rationale is that in one of the studies we discussed, AEA was observed to interfere with rats' ability to learn avoidance behavior.[50] In that study, the rats were administered shocks in a predictable fashion, and the speed at which they avoided subsequent shocks was taken as a measure of how well they learned.

This chart shows the latency time to enter the shock compartment with all four paws after the first treatment.[50] Anandamide may thus interfere with the formation of long-term memories (or at least at the 24 hour period), so taking it when you need to learn something is probably not advisable.

Although rats who were given AEA during the learning process did just as well as control rats in the short term, i.e. when re-tested 15 minutes after learning to avoid the shocks, they did much worse than control rats when tested 24 hours later.[52]

There's not a ton of anandamide-specific research on this subject, but it's well-known that exogenous cannabinoids like THC and CBD can impair learning by activating the same receptors – cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) included – as AEA.[65]

Targeted activation of the CB1 receptor has also been shown to interfere with the biochemical processes that drive long-term potentiation, your brain's process of consolidating short-term memories into long-term ones.[66]

FastBliss: NNB Nutrition’s Tested Anandamide Supplement

NNB Nutrition is a highly-trusted, innovative ingredient development company with an elite team of over 100 scientists from over 10 countries.

NNB Nutrition is an industry-leading novel ingredient developer that's been ahead of the curve with several ingredient developments. They were the first company to develop a stable form of L-BAIBA (sold as MitoBurn) and L-ergothioneine (sold as MitoPrime), and they produce the vast majority of ketone salts on the market as well.

Now they've done it again, with a commercially stable form of anandamide called FastBliss. It comes in two forms - oil and powder - each with separate yields.

FastBliss-specific data

NNB Nutrition's FastBliss is a stable, tested, standardized form of anandamide that comes in both oil and powder form.

Through NNB's ongoing research on FastBliss (safety data is in the next section), they've replicated some of the above data. It's not yet published, and this section will be updated when more information is available, but here's a sneak peak:

-

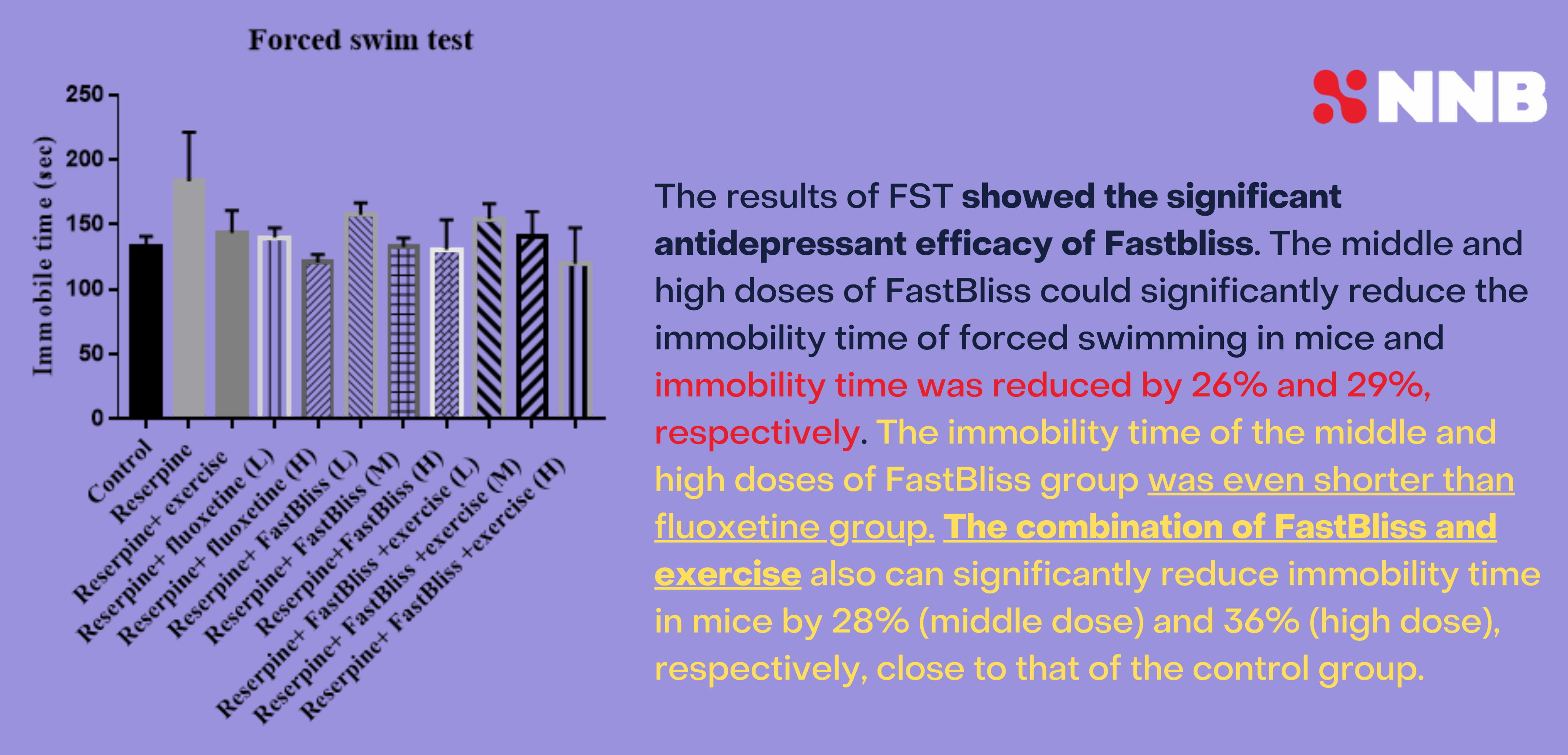

Forced swim test

In a forced swim test on mice, combining FastBliss with exercise led to significantly reduced immobility time. Its effects were comparable to -- and even better than -- known therapeutics, especially when combined with exercise.

-

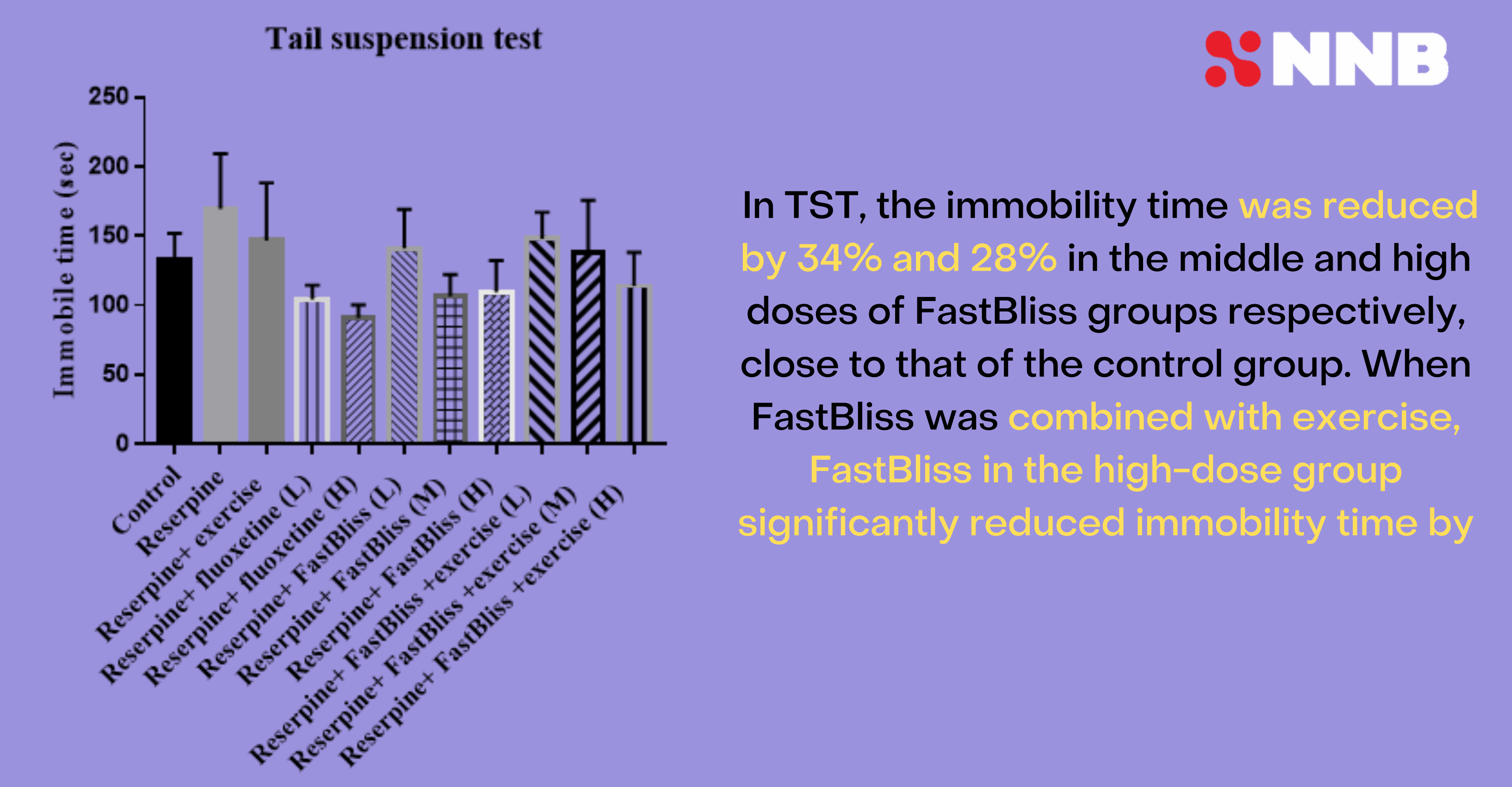

Tail suspension test

NNB's researchers also determined that mice given tail suspension tests are significantly more vigilant, with immobility time reduced 34% and 28% in the middle and high dose groups of FastBliss, respectively, compared to control.

NNB FastBliss anandamide tail suspension test, based upon pre-published data. Image courtesy NNB Nutrition.

This means that there seems to be a sweet spot in terms of the ingredient. But when combined with exercise, the highest-dose FastBliss group performed best, so it may depend on application.

A GRAS panel has convened

NNB is also in the process of assessing safety, and looking to achieve Generally Recognized as Safe status sometime in the 2023 calendar year. This brings us to some of the preliminary safety data that we can share:

Anandamide Safety and Toxicity

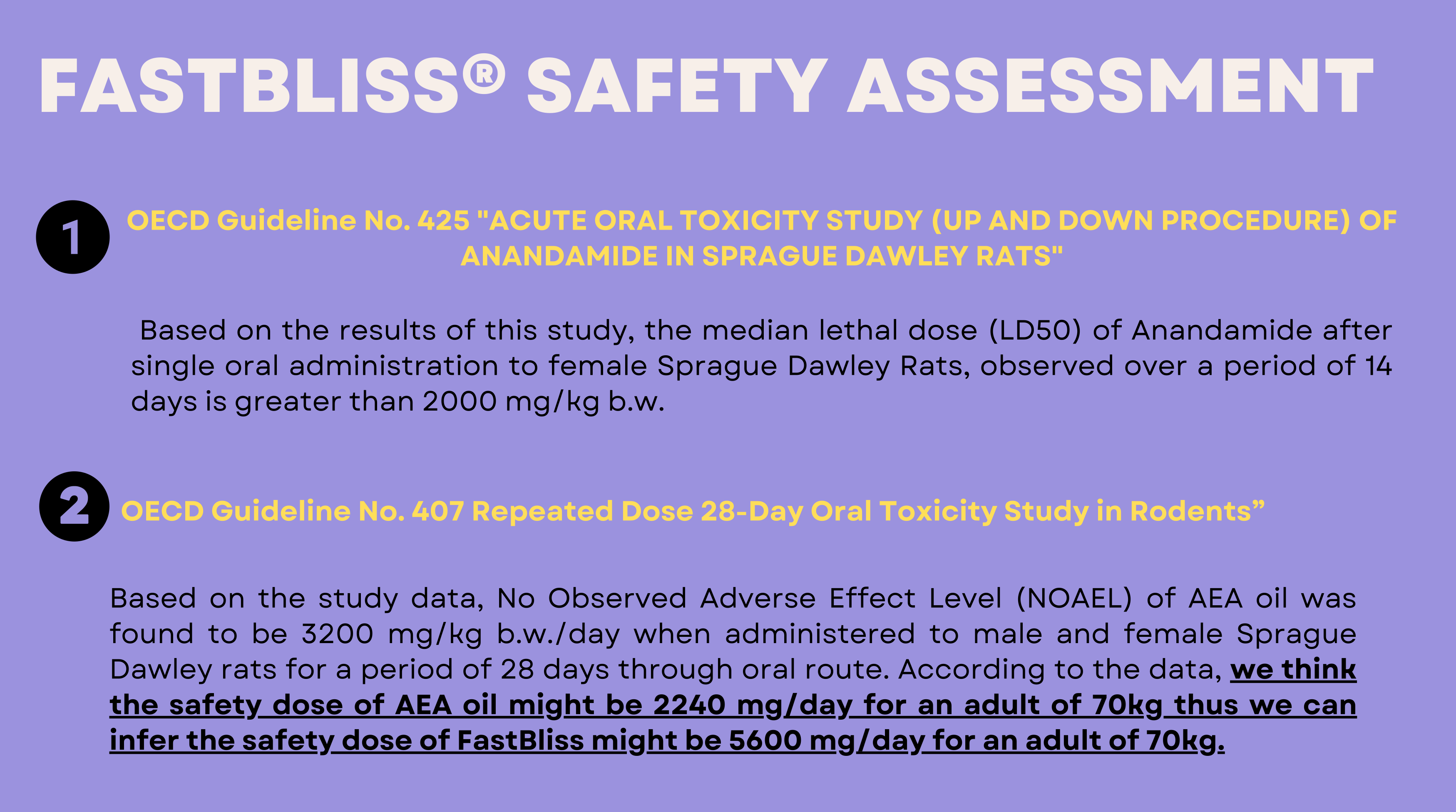

Part of NNB Nutrition's ongoing GRAS panel is to determine an LD50 (median lethal dose) after single oral administration in female Sprague Dawley Rats observed over a period of 14 days, according to OECD Guideline No. 425.[67] Preliminary data shows that the LD50 is greater than 2000 mg/kg body weight -- but we are awaiting official confirmation and publication.

Additionally, OECD Guideline No. 407 standardizes an oral toxicity test for 28-day repeated dosing.[68] Based on preliminary data, no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) of AEA oil was found at up to 3200 mg/kg b.w./day through oral route when administered to male and female Sprague Dawley rats over the course of 28 days.

Pre-published data from NNB Nutrition's safety research on FastBliss anandamide. Image courtesy NNB Nutrition

This leads us to believe that AE can be safely dosed up to roughly 2240 mg/day for an adult of 70kg -- far more than any supplement currently containing anandamide.

More will be known once the data is reviewed and published, and this area will be updated at that time.

Dosage

Glaxon GRIT is a natural pain support supplement with a low dose of FastBliss anandamide to try!

It's still tough to determine human doses, and the dosage will also depend on the effects desired.

Below, we suggest a supplement that contains anandamide at 25 milligrams, alongside several other complementary ingredients to provide natural pain support. However, NNB Nutrition suggests dosage of FastBliss in ranges of 170 to 800 milligrams for the oil format, and 400 to 1500 milligrams for powder format.

Try FastBliss in Glaxon GRIT

The first supplement to use FastBliss is Glaxon GRIT, which synergizes turmeric and boswellia with two endocannabinoids - anandamide (FastBliss) and beta-caryophyllene (from black pepper). It also combines two well-known botanicals in white willow bark and devil's claw.

It uses just 25 milligrams of anandamide from FastBliss, but is a great way to start feeling the effects of this impressive compound.

Conclusion: Anandamide has a plethora of interesting benefits

Endocannabinoids have proven themselves to be fascinating molecules, and anandamide, as the first one discovered, leads the way in their research. Reducing inflammation, improving immunity, facilitating social behavior, helping manage pain, anxiety, sleep, and mood – these are all extremely promising use cases of anandamide.

The additional applications of appetite stimulation and vasodilation to coincide with the mood-boosting effects -- especially in a workout setting -- make the ingredient a unique addition to any brand's arsenal, and it can be used in several different ways.

While we don't recommend AEA as a study aid, it has a ton of benefits and there are likely far more to be discovered from this and other related molecules. There aren't a ton of human or animal studies on supplemental anandamide either, and we're hoping for more as time comes (this article was originally published in February 2023).

It's early to determine how successful the ingredient will be, but when used and marketed appropriately, we can foresee some incredible benefits to help a society that's simply over-stressed and over-inflamed. Brands who missed out on CBD may not want to miss out on this -- and the two can be stacked for even more potential.

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

Glaxon GRIT – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)