As you can probably guess from their name, Myprotein specializes in high quality protein supplements, but in recent years they've branched out into tons of other product categories. This is especially true with their Pro Range, which has product names that begin with the word "THE" (example: THE Whey and THE Pre-Workout).

Myprotein THE Thermo-X is a unique fat burner with 100mg caffeine per serving, but higher doses of long-lasting theobromine and theacrine to pair with the thermogenic capsaicin!

Now, with THE Thermo-X, Myprotein is taking a stab at one of the supplement industry's mainstays: fat burners.

Myprotein THE Thermo-X: A unique, lower-caffeine fat burner

At a time when the industry is moving toward brown adipose tissue (BAT) upregulation as the primary fat-burning strategy, Myprotein comes at you with something a little different THE Thermo-X kicks off with a huge dose of theobromine, a longer-lasting methylxanthine alkaloid, and pairs it with a huge long-lasting dose of theacrine. Then it follows those with 100 milligrams of caffeine per two-capsule serving and a bunch of appetite-suppressant ingredients.

So right off the bat, we can tell you that the stim-blend in here is going to be far different than what you're used to with the average fat burner.

Before we talk about how it works, let's check the PricePlow news and deals:

Myprotein THE Thermo-X – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Ingredients

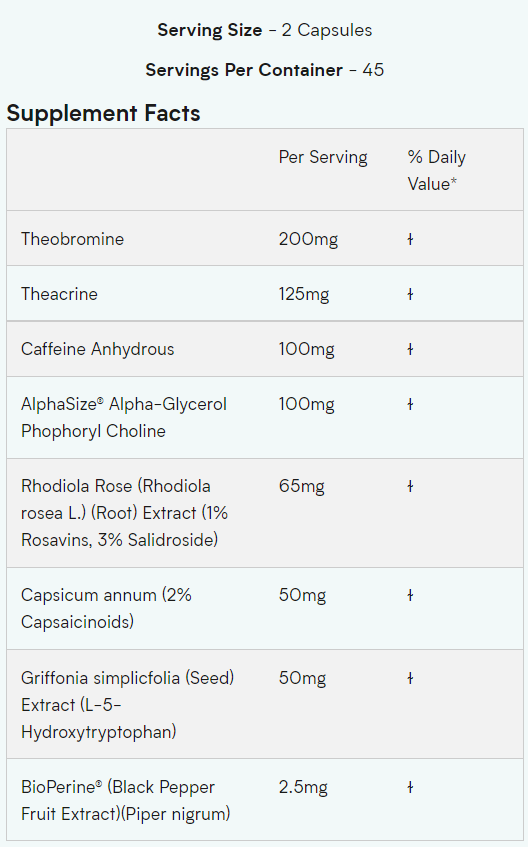

In a single 2-capsule serving of THE Thermo-X from Myprotein, you get the following:

-

Theobromine – 200 mg

Theobromine is a methylxanthine alkaloid found in tea, coffee, and chocolate, and more.[1]

Much like its close cousin, caffeine, theobromine inhibits phosphodiesterase, an enzyme responsible for breaking down cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a second messenger hormone that tells your cells to burn glucose and fatty acids for energy.[2]

Theobromine can fight fatigue by acting as an antagonist for adenosine,[3] a nucleotide that builds up in your brain during the waking state.

Elevated cAMP levels stimulate the expression of a protein called peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC-1α).[4] This helps drive a process called fat browning, in which white adipose tissue (WAT) is literally colored brown by the proliferation of new mitochondria.

When this process of mitochondrial biogenesis goes on long enough in WAT for the change in appearance to be palpable, we actually refer to it as brown adipose tissue (BAT). For anyone looking to burn fat, BAT is a great metabolic asset to have because it's the site where a process called non-shivering thermogenesis (NST) occurs — when extra calories are burned and converted to heat.

The ability to convert WAT to BAT is why theobromine is considered a thermogenic substance.[5] It's capable of significantly upregulating thermogenesis and, hence, increasing a person's daily caloric expenditure.

Ingredients like this really put the thermo in Thermo-X.

-

Theacrine (as TeaCrine) - 125 mg

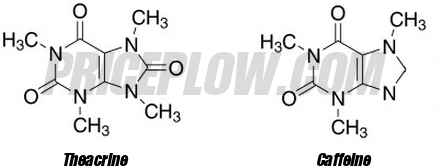

Next we have another caffeine-like xanthine alkaloid, in the form of theacrine.

Similar to caffeine (and theobromine), theacrine can increase both mental and physical energy[6] by inhibiting phosphodiesterase.[7]

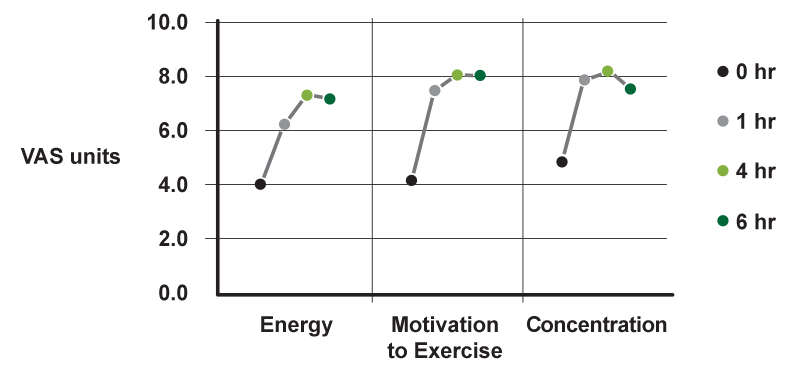

Want longer-lasting energy? Here it is. Effect Size of 200 mg dose of Teacrine over course of 7-day repeated dose study relative to baseline on: Energy: 0.63, Motivation to Exercise: 0.58, Concentration: 0.6

Theacrine helps fight feelings of fatigue by blocking the action of adenosine at the receptor level.[8] It also upregulates dopamine function by stimulating dopaminergic receptors.[9] Both of these effects can help increase motivation and focus while adhering to a dietary or exercise regimen.

Another key similarity between theacrine and the other xanthines is its ability to drive thermogenesis, thus increasing your daily caloric expenditure.[10]

-

Caffeine anhydrous – 100 mg

As the most pervasively used legal psychoactive drug in the world, caffeine really needs no introduction. What's interesting here is the dose - just 50 milligrams per capsule, really allowing you to titrate your caffeine intake with THE Thermo-X.

Caffeine is capable of crossing the brain-blood barrier, which is what gives it the ability to substantially affect mood, fatigue, and mental and athletic performance.[11] And of course, like its cousins theobromine and theacrine, caffeine fights feelings of fatigue by antagonizing adenosine,[12] which is why coffee drinkers the world over reach for that morning cup first thing after waking.

Theacrine is similar to caffeine, but definitely not the same, providing a possibly far longer lasting effect.

Caffeine gets a lot of attention for its anti-fatigue effects, but just like theobromine and theacrine, it also has a beneficial effect on cellular energy production. Its mechanism of action is that, common to the xanthines as a class, it inhibits phosphodiesterase, thus elevating cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels.[13,14]

As we said earlier, cAMP is a metabolic master switch, and turning it up means you'll burn more calories in a day.[15] Caffeine's effect on cAMP makes it a particularly good fat-burning compound, and it has been shown to increase the body's rate of fat burning by as much as 50%.[16]

Caffeine's ability to upregulate cellular energy production makes it a great ergogenic aid, capable of increasing several dimensions of athletic performance, including strength, speed, and endurance.[17] What makes caffeine (and the other methylxanthines) great for fat-burner formulas is its effect on the brain – it increases attentiveness,[18,19] alertness,[19] reaction speeds,[18] and working memory.[20]

Nootropic benefits aren't something most people think about in the context of a fat-burner supplement, but we think supporting mental function is important. When you're dieting to lose weight, your mental status can often feel impaired, so anything that helps you stay in peak condition mentally can ultimately improve adherence and maximize your chance of body-recomposition success.

-

AlphaSize 50% Alpha-Glycerylphosphorylcholine – 100 mg

Alpha-glycerylphosphorylcholine, fortunately abbreviated as alpha GPC, is a uniquely effective form of the essential B vitamin, choline.

Choline is important as a building block for your cells' phospholipid bilayer membranes, the fatty envelopes that surround and enclose the interior of all your body's cells. These membranes are crucial for cellular health and function – they act like borders for your cells, keeping nutrients in while protecting organelles from pathogenic or toxic substances in your bloodstream.[21]

Choline is also a key precursor to a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which drives the process of memory consolidation by facilitating communication between neurons.[22]

The more choline you give your body, the more acetylcholine it can produce, which ultimately leads to improved cognitive performance. Key mental abilities like memory, learning, attention, alertness, and even psychomotor skills like balance and coordination can benefit from supplemental choline.[23,24]

We're fans of alpha GPC, among other forms of choline, owing to its exceptional bioavailability and ability to cross the blood-brain barrier.[25] However, the dose isn't massive here, and it won't contribute to a ton of your day's worth of choline.

A potential stackable fat burner!

If you're a regular user of Myprotein THE Pre-Workout (which is also low-caffeine at 150 milligrams per day), you'll also get a pretty good shot of choline inside, so the two could make a very solid stack. Normally we don't recommend combining stim-based fat burners with stim-based pre-workouts, but in this case, most athletes can handle the total caffeine load of one serving of each!

-

Rhodiola rosea (Rhodiola rosea L.) (Root) Extract (1% Rosavins, 3% Salidroside) – 65 mg

Rhodiola is often touted as an anti-stress supplement, but did you know it has potent weight-loss effects as well?

First of all, we should note that there's actually quite a bit of overlap between combating the effects of chronic stress and reversing or preventing undue weight gain – high levels of cortisol, the principal mammalian stress hormone, have been shown in animal and human studies alike to increase an individual's risk of obesity.[26,27]

Rhodiola: Our favorite feel-good herb with some additional workout boosting properties, thanks to the salidroside inside. Image courtesy Wikimedia

Since Rhodiola extracts have been shown to blunt the rise in cortisol that usually follows stressful events,[28,29] Rhodiola should, in theory, help discourage obesity by preventing the hypercortisolism that can lead to obesity.

Rhodiola's anti-obesogenic effects

However, Rhodiola can also fight obesity directly: Extracts of this plant have been shown to inhibit the growth of new fat cells (a process called adipogenesis),[30] as well as increase your body's rate of lipolysis, which is a fancy word for fat burning.[30]

Rhodiola also improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity,[31] which, as most of us know by how, is a huge factor in metabolic health and, in the long run, body composition.

It also can help suppress appetite by upregulating an orexigenic compound called peptide Y.[25,32] This is obviously favorable for weight loss.

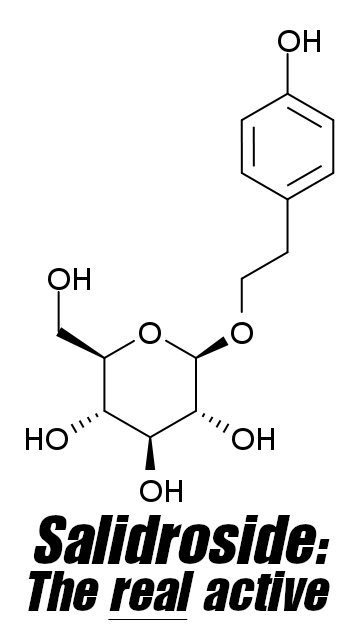

Rosavins vs. Salidrosides

New research is showing that rhodiola extracts high in salidroside are the ones with the most potential... so why do so many supplements have non-existent standardizations?

The study we cited on Rhodiola's ability to inhibit adipogenesis and upregulate lipolysis takes pains to point out that the effects of Rhodiola can be mostly attributed to one of its bioactive constituents – namely, the salidrosides the occur naturally in the Rhodiola plant.

There are a few different kinds of Rhodiola extract on the market. Sometimes they're sourced from different species of Rhodiola, other times they're standardized for different bioactive constituents.

In general, we like seeing high-salidroside extracts of Rhodiola because the salidrosides seem to confer more benefits than the rosavins.[21,22]

And fortunately for us, we have a fairly high-salidroside extract in THE Thermo-X – 3% by weight. That's good news because in the study we cited, a 3% salidroside extract of Rhodiola was the one shown to be most effective at inhibiting lipogenesis and upregulating lipolysis!

Other benefits of salidrosides

Salidrosides can also:

- Upregulate long-term potentiation (LTP), the neurological process behind memory consolidation[24]

- Upregulate autophagy by acting on mTOR[25]

- Increase cellular oxygen uptake[33]

- Increase the expression of catecholamine neurotransmitters, like dopamine and adrenaline[34]

- Inhibit monoamine oxidase,[35] the enzyme responsible for degrading neurotransmitters

- Improve cognitive performance[36]

- Reduce stress and anxiety[37]

- Improve mood[37]

- Mitigate depressive symptoms[38]

- Decrease physical and mental fatigue[39,40]

- Increase athletic performance[41]

Although the benefits on this list might not be directly related to fat burning, it's pretty easy to see how most of these would be helpful while adhering to a strict diet and exercise regimen. While we wish the dose were greater, at least there's some good stuff standardized here.

-

Capsicum annum (2% Capsaicinoids) – 50 mg

Cayenne pepper is the colloquial name for the pepper plant Capsicum annum.

The main bioactive constituents of this pepper, capsaicin and related capsaicinoids, have been known to supplement formulators and consumers for decades as potent fat-burning compounds, thanks to their thermogenic effects.[42]

Capsaicinoids have also been shown to suppress appetite,[43] which, again, is pretty obviously a useful thing for anyone who's trying to slim down.

An extract with 2% capsaicinoids, dosed at 50 milligrams, gives us 1 milligram of capsaicinoids per 2-capsule serving, which is only half the minimum effective dose of 2 milligram capsaicinoids for weight management.[44] So, in order to get the most out this particular ingredient, we recommend double-dosing the product by taking 4 capsules per 24-hour period. According to Myprotein's website, that's the maximum recommended dose of THE Thermo-X.

Capsaicin can also decrease pain sensitivity, which could help you push yourself harder in the gym.[45]

Note that in some individuals, capsaicin can increase blood pressure and heart rate,[42] which is probably one of the reasons why Myprotein recommends starting with 1 capsule of THE Thermo-X and working your way up to the full dose, whether that ends up being 2 or 4 capsules. As always, talk to your doctor before starting a new diet or supplementation regimen.

-

Griffonia simplicifolia (Seed) Extract (L-5-Hydroxytryptophan) – 50 mg

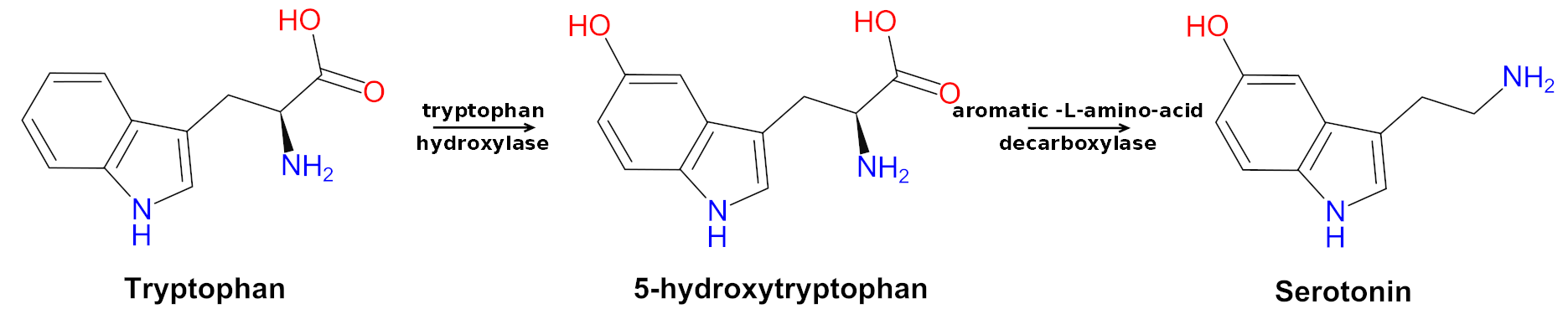

L-5-Hydroxytryptophan, or 5-HTP, is a serotonin precursor extracted from the Griffonia simplicifolia plant.

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that's responsible for helping regulate mood and feelings of happiness. But since it's also important for appetite regulation,[46] managing serotonin levels is relevant to the process of losing weight.

The Tryptophan to Serotonin pathway by way of 5-HTP. Don't have enough tryptophan around because of weak diet? Get more here.. and below we discuss how Vitamin B-6 can add additional help. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

It's been shown that 5-HTP supplementation can reduce cravings,[47] which are a huge problem for most dieters, and can increase feelings of satiety following a meal.[48-51]

As we discussed above, stress hormones can increase a person's risk of unwanted fat gain.[26,27] As it turns out, so can sleep deprivation, or any other kind of sleep disturbance.[52,53]

Since 5-HTP is commonly taken as an anti-stress supplement that improves sleep quality,[54,55] it's not much of a theoretical leap to say that 5-HTP can probably encourage healthy body composition by those mechanisms.

Other studies have found that 5-HTP supplementation can help dieters make healthier choices,[50] and improve adherence to dietary prescriptions.[51]

-

BioPerine – 2.5 mg

BioPerine is a piperine extract sourced from black pepper. It's usually included as a bioavailability enhancer since it improves the intestinal transport of whatever other ingredients it's stacked with.

Piperine, a powerful antioxidant alkaloid,[56] does this by inhibiting stomach enzymes that usually break down ingredients before they can reach the intestines, where they're actually absorbed into the bloodstream.[57]

Piperine's anti-obesity mechanisms

Piperine also increases the expression of a protein called glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4), which causes your muscle cells to take up glucose. This helps keep blood glucose levels under control, thus leading to long-term improvements in overall metabolic health.Bioperine is the trusted, trademarked form of black pepper extract that promises 95% or greater piperine, the part of black pepper with all the activity!

In mice, GLUT4 upregulation has been shown to even reverse insulin resistance and diabetes.[58]

Piperine also improves insulin sensitivity while removing adipose tissue from the liver.[59]

This is important since the accumulation of adipose tissue in the liver can lead to a condition called non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is closely linked to metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and obesity.[60]

Piperine can also increase the number of calories your body burns per day by upregulating a process called non-shivering thermogenesis, in which your body burns glucose and fatty acids off as heat.[61]

Conclusion

On one hand, THE Thermo-X's formula is pretty straightforward – lots of work is done by appetite-suppressant ingredients, which obviously make it easier to eat less. On the other hand, it's very unique -- higher doses of both theobromine and theacrine and lower doses of caffeine will lead to a long-lasting but lower-stim effect.

But with lower amounts of caffeine in both this product and THE Pre-Workout, many users will be able to stack the fat burner and pre-workout from The Pro Range -- something that is almost never a possibility from brands! So it's pretty cool how this series turned out.

But also, there are a lot of anti-stress and sleep-promoting ingredients in here too, which we appreciate because it's easy to overlook the crucial role that hormones and sleep play in establishing and maintaining healthy body composition.

Myprotein THE Thermo-X – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)