Spicy food.

It's one of those things that you either love or hate. As any serious student of global gastronomy can tell you, most cultures love it – and even within cultures that don't, it's easy to find individuals who do.

Capsaicinoids are well-known for their metabolic benefits, but there's far more under the hood. aXivite phenylcapsaicin enhances performance with less burn. Discover SEE Nutrition's innovative solution for both dieters and athletes.

But why are human beings so fascinated by spicy food? After all, it burns your mouth -- and possibly other parts of your body -- so why eat it at all? Is the behavior based on a reward calculus, in which the pleasure of endorphin and dopamine release outweighs the pain of eating it?

We're sure hedonic considerations are part of it, but as it turns out, there are great functional and physiological reasons for eating spicy food. For example, spicy foods are known to improve heart health by reducing bad cholesterol levels[1] and promoting blood flow.[2] They also have anti-inflammatory properties,[3-5] which can help alleviate pain and reduce the risk of chronic diseases. Additionally, consuming spicy foods can enhance digestion by stimulating stomach acid and digestive enzyme production.[6]

Research is finding that most of these benefits come down to a single molecule – capsaicin. And one company has found a way to make capsaicin even more effective.

aXivite Phenylcapsaicin – Health Benefits Of Spicy Food, Without as Much Burning

There are a lot of different compounds responsible for giving spices that characteristic burning sensation. For the most part, these compounds are alkaloids that fall into one of two categories: capsaicinoids, which are named after capsaicin, and capsinoids.

Capsaicin: The most prevalent spicy alkaloid

There are several alkaloids in spicy peppers, but capsaicin is hands down the most extensively studied of all the capsaicinoids and capsinoids. There are several reasons for this, but the biggest one is simply that of all these alkaloids, capsaicin is the most abundant in pepper plants. With minor variations between species, capsaicin accounts for about 71% of all capsaicinoids in pepper plants[7] – and because capsaicin has such a huge impact on the overall taste and quality of a pepper, capsaicin content is a major determinant in the commercial profitability of any given pepper.[8-11]

Besides being the most abundant alkaloid in peppers, capsaicin (along with a related compound called dihydrocapsaicin) is also the most pungent.[12]

Benefits of capsaicin

By now, a veritable mountain of research has been conducted on capsaicin, and it has found that consumption of this remarkable alkaloid can:

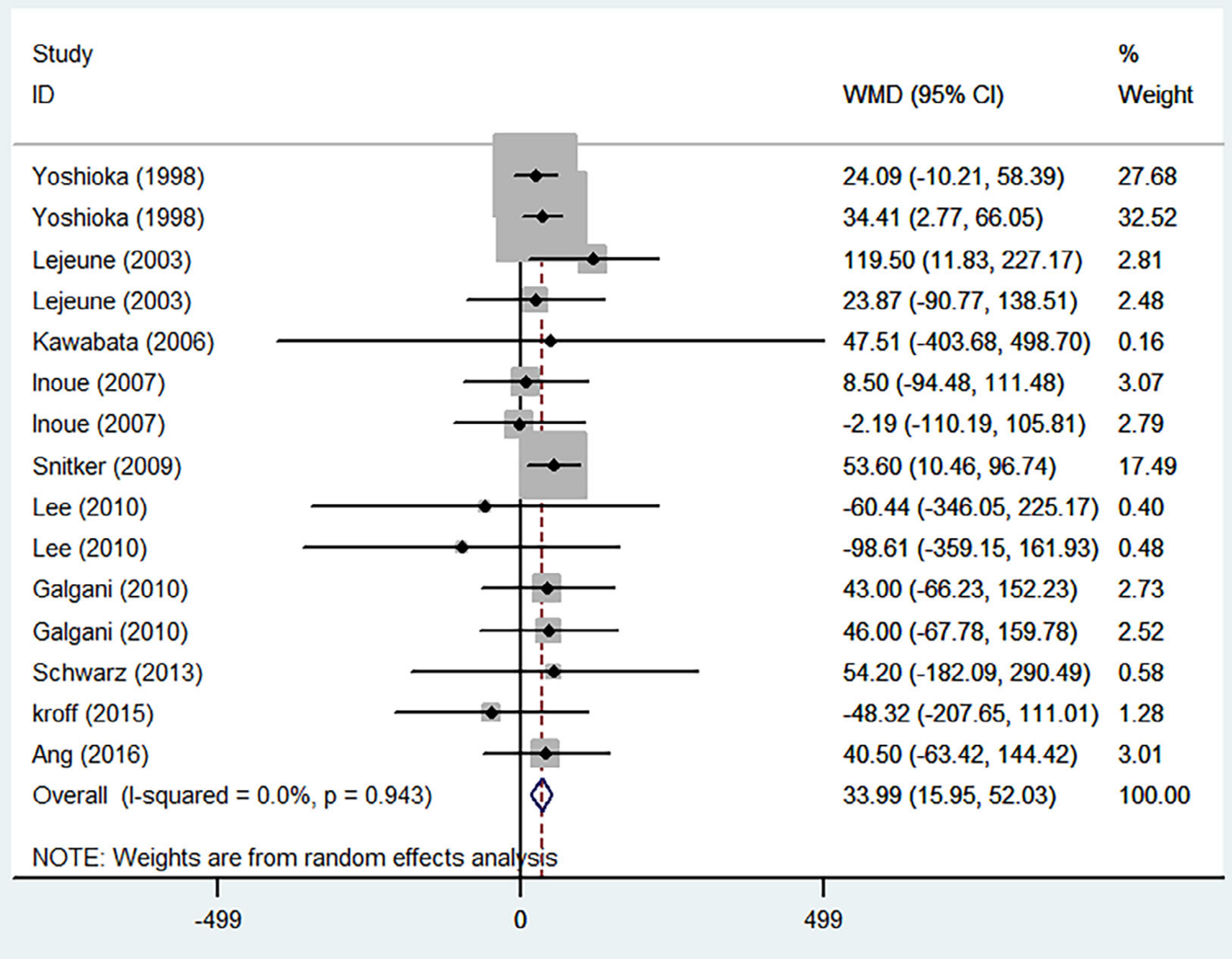

- Boost metabolism and promote weight loss, primarily by increasing thermogenesis, helping the body burn more calories,[13] and reducing appetite[14]

-

A meta-analysis showed that capsaicinoids significantly improve resting metabolic rate.[13] Science repeatedly confirms that they're effective, but can we simultaneously make them more effective while reducing the dose and spice? The answer, as we'll see in this article, is yes.

Improve cardiovascular health by reducing LDL cholesterol,[1] discouraging blood clot formation,[15] increasing nitric oxide production,[5] enhancing blood flow via vasodilation,[2] and decreasing risk of hypertension[16]

- Reduce inflammation[3,4]

- Fight oxidative stress, as capsaicin has demonstrated antioxidant properties[17]

- Increase insulin sensitivity,[18] which can support long-term metabolic health and body composition

- Improve digestion by exerting anti-inflammatory effects on the composition of the gut microbiome[19]

- Improve mood and mental health by triggering the release of endorphins and dopamine, which ultimately decrease perceived stress[20]

- Increase lifespan and decrease risk of overall mortality[21]

And believe it or not, this is just a partial list of all capsaicin's probable benefits – for the sake of brevity, we're just naming the ones that currently have the best evidentiary support.

Capsaicin as an ergogenic aid

That being said, let's briefly talk about just one more potential benefit of capsaicin supplementation that doesn't get as much attention: its ergogenic effects.

One of capsaicin's big mechanisms of action, which underlies most, if not all, of its benefits, is the alkaloid's ability to stimulate transient receptor vanilloid 1 (TRPV1).

TRPV1 activation: Afferent III and IV Nerve Fibers

When it comes to ergogenic effects, consider the fact that TRPV1 is expressed at particularly high levels in afferent III and IV nerve fibers, which play a key role in the onset of central and peripheral fatigue during exercise.[22] TRPV1 activation has been shown to modulate these nerve fibers by:

- Desensitizing them to pain and discomfort

- Improving blood flow and metabolic efficiency, and

- Enhancing the release of endorphins

...all of which can increase athletic performance, particularly endurance.[23]

Because of this, there's a small but compelling body of evidence testing capsasicin's ability to improve athletic performance in humans. Research has shown that capsaicin can, for example, improve cardiovascular efficiency during high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and subsequent weightlifting.[24]

Dosing problems: GI distress at ergogenic doses

There's a problem though: the study we cited above, which found significant improvement in performance from capsaicin, used a dose of 24 mg, which is quite a lot. Even encapsulated formulations of capsaicin have been shown to cause significant gastrointestinal irritation at 25.8 mg/day.[25]

We want the benefits, but we don't want those side effects. Thankfully, a company named SEE Nutrition has an elegant solution for us in the North American dietary supplement industry:

aXivite Phenylcapsaicin – Vastly Higher Bioavailability

So, in order to get the full ergogenic benefits of capsaicin, it might help us to have a high-bioavailability capsaicin formulation, which would enable us to achieve the same effect at a smaller dose.

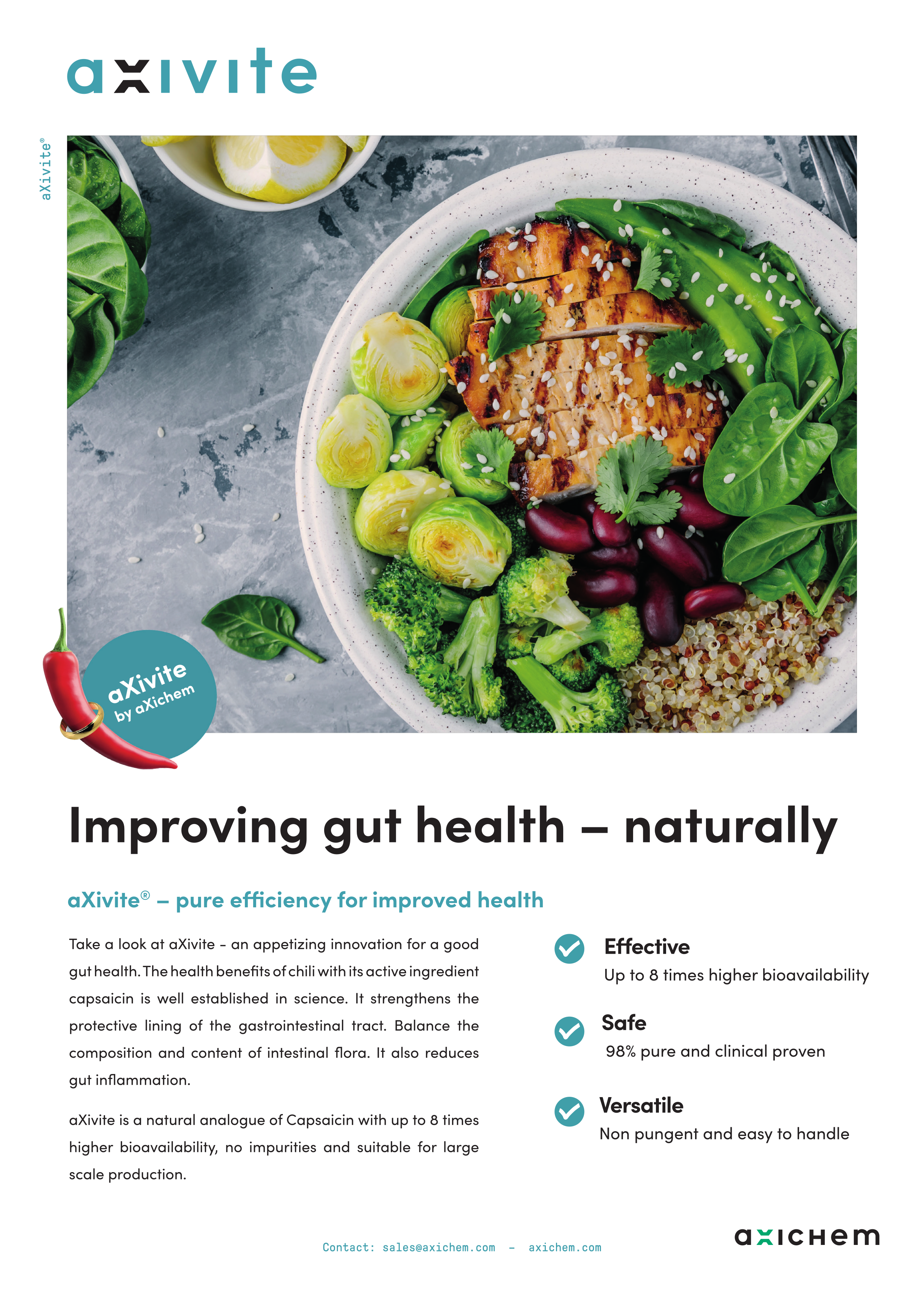

That's exactly why a company named aXichem developed aXivite.

At its core, aXivite is a capsaicin molecule chemically bound to a phenyl group (chemical formula C6H5). Phenyl group binding is a biochemical engineering technique that can significantly increase the bioavailability of the target molecule by improving its chemical stability, and increasing its solubility and lipophilicity.[26]

Yet phenylcapsaicin is close enough to capsaicin that it similarly triggers the capsaicin receptor. Preliminary internal research has shown that thanks to this chemical similarity, aXivite and capsaicin have similar effects on human cells – and the internal data shows that phenylcapsaicin is just as effective as capsaicin at activating the TRPV1 receptor.

Microencapsulated for more support

But the phenyl group is only half of the aXivite equation. The other half is aXichem's proprietary microencapsulation process, which coats the molecule, protecting the user from the spicy taste as well as the potential gastrointestinal irritation that's associated with the use of ordinary capsaicin. Just like capsaicin, phenylcapsaicin has a spicy taste, so it's useful to encapsulate it to protect the digestive tract.

According to aXichem's internal data, their innovative engineering has resulted in phenylcapsaicin having eight times greater bioavailability than standard capsaicin. This means you can achieve the same effect at one-eighth of the dose – an advantage that, when paired with aXichem's microencapsulated preparation, dramatically decreases the possibility of adverse effects.

Excellent for sports nutrition applications at a fraction of the dose

This makes aXivite the obvious choice for any sports nutrition applications – in order to achieve the 12-24 mg dosing range we typically see in studies on capsaicin's ergogenic effects, you'll only need 1.5-3 mg of aXivite!

So does it work for sports nutrition applications?

aXivite As Ergogenic Aid – Study Results

Fortunately, there have already been three excellent studies on aXivite. Although this isn't a ton, these are of a much higher quality than what we typically see in the research literature on generic capsaicin. Overall, they paint a very compelling picture of aXivite's potential as an ergogenic aid.

The same lead researcher, Dr. Pablo Jimenez-Martinez, was behind all three of these studies, which were published in 2023. We have to say, the design and data analysis of these studies is exceptionally rigorous, and we're pretty impressed with the amount of thought that went into them.

-

Improves rep velocity and RPE during 70% 1RM squats (2023)

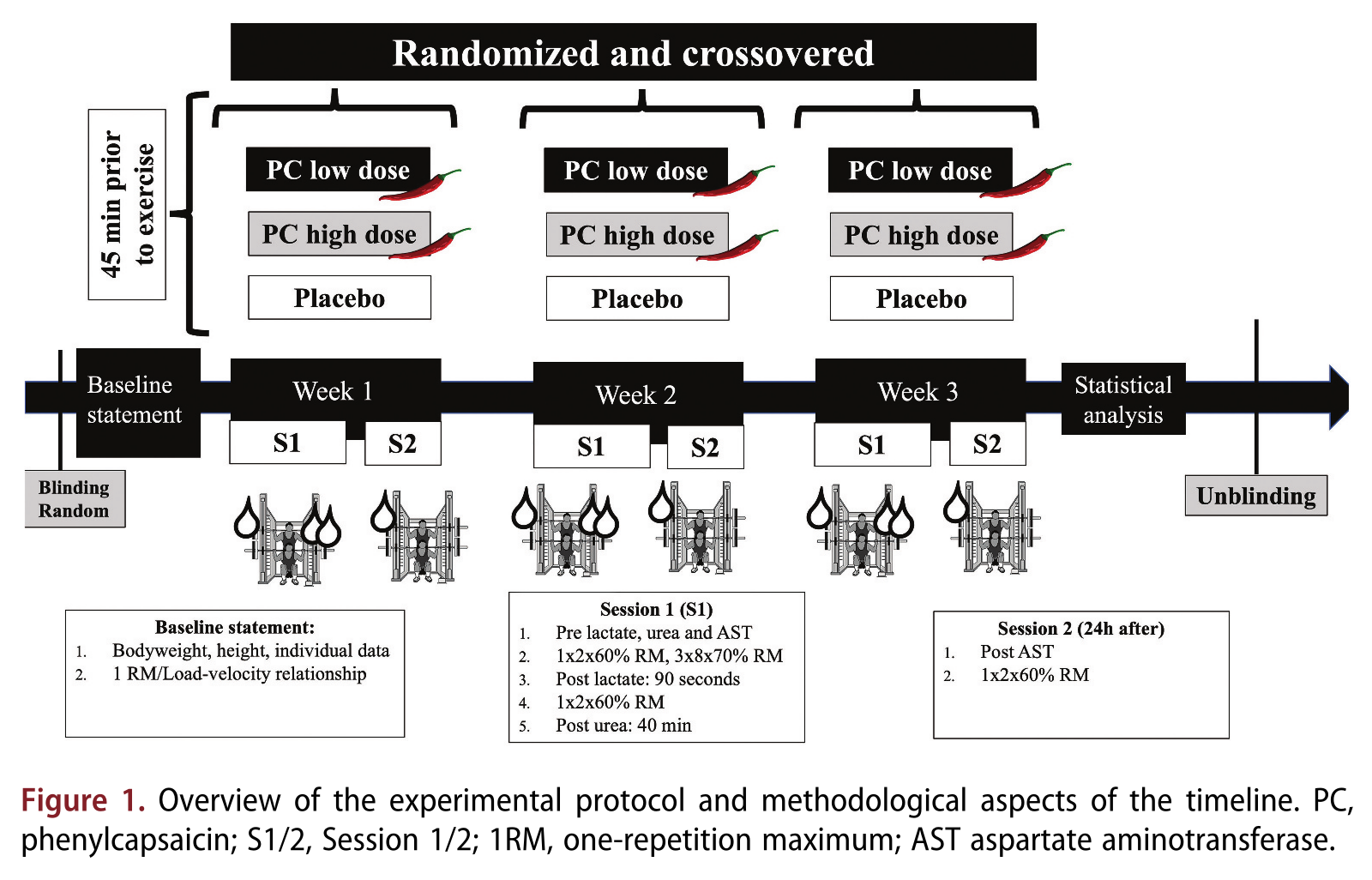

Perhaps the most compelling of the aXivite studies is one that looked at the supplement's ability to improve resistance training performance, muscle damage, protein breakdown, metabolic response, perceived exertion, and recovery during squats.[27]

A triple blinded study

This was a randomized, placebo-controlled study, which is what we expect to see in first-rate study design – but instead of the usual double blinding, this was a triple-blinded study. Whereas in a double-blind study, both the study participants and researchers are unaware of which treatment condition the participants have been given, a triple-blind study actually blinds the data analysts who statistically analyze the study results as an unbiased third party. They had no clue what they were even looking at -- they just had to determine that the numbers were significant.

Study methods - well-trained population

This study was conducted in 25 healthy men with an average age of 21, and an average squat 1 rep max of 1.66 kg per kg body weight.[27] So, this means that for a 90 kg (200 lb) male, we would expect a 328 lb 1 rep max, which is very respectable. In fact, the study specifies that participants had at least 2 years of resistance training under their belts.

Point being: this is a trained population, which immediately bumps up the study's credibility. After all, it's much harder for an ergogenic aid to achieve efficacy in a trained population, which gives that much more weight to any observed benefit.

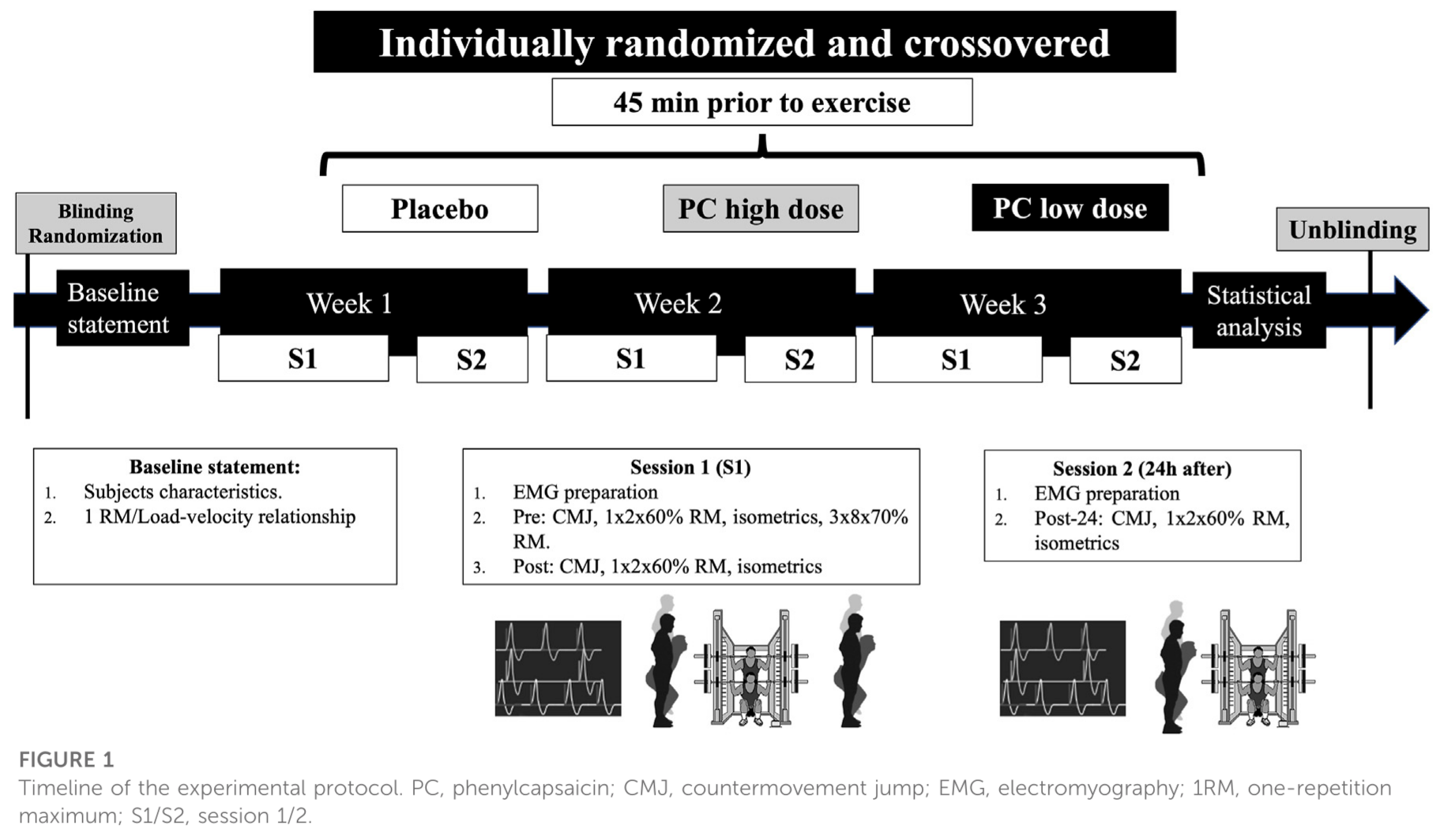

It was a crossover study, which is typically considered as the gold standard for acute studies designs. That means the subjects served as their own controls – they were randomly assigned to one treatment condition, then repeated the study under the other treatment condition after a washout period. This eliminates individual variability, since every subject completes the study under all conditions. However, due to the difficulty to perform designs like this in the long-term, crossovers are mostly used in acute studies.

There were three different treatment conditions in this study:

- Placebo

- 0.625 milligrams of aXivite (the low-dose or LD group)

- 2.5 milligrams of aXivite (the high-dose group, HD).

Once they'd been randomly assigned to their initial treatment condition – placebo, LD, or HD – the subjects visited the study lab twice a week for three weeks. Each study week consisted of a main experimental session and a follow-up session.

During the main experimental period, for the first session of each week, the researchers had the subjects do 1 set of 2 squats at 60% 1RM followed by a performance test consisting of 3 sets of 8 squats at 70% 1RM. They then cooled down with another 1x2 at 60%.

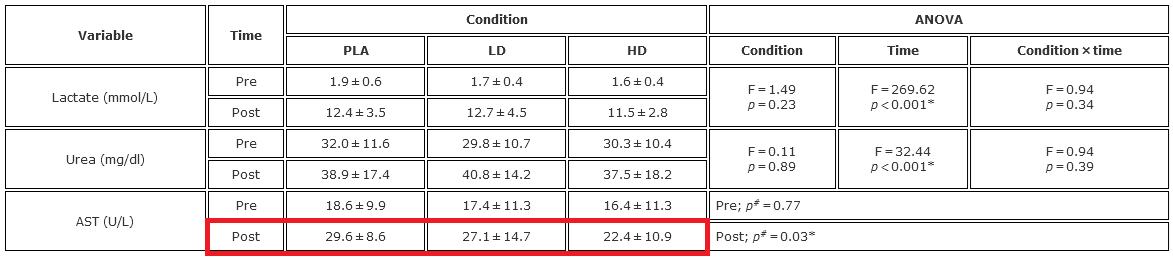

The researchers measured subjects' lactate and urea, as well as their levels of aspartate transaminase (AST), an enzyme that's expressed in response to exercise-induced muscle damage.

During the followup session (session 2), the researchers measured AST and had the subjects perform another 1x2 at 60% 1RM.

The study also used metrics for subjective fatigue and recovery assessment, including perceived recovery status (PR)S, rating of perceived exertion for overall body (RPE-OB), and rating of perceived exertion for active muscle (RPE-AM).

Gathering load-velocity relationship

The really cool and important thing about this study is that prior to beginning the study, each participant performed a progressive loading test in which an initial load on the bar was gradually increased through a sequence of repetitions until that participant's mean propulsive velocity (MPV) dropped to 0.50 meters per second. Then, the participants performed a series of repetitions with light, medium, and heavy weights on the bar.

The researchers used this data to calculate a load-velocity relationship for each participant. It's not often that we see a resistance exercise study use velocity as an outcome to measure, but it makes sense for athletes who need impact and intensity. This is important because measuring velocity with a linear transducer we can ensure that the performance and fatigue effects (e.g., velocity loss from the first to the last repetition with a matched load) are measured sensitive and objective, something that is not common in sport supplement sciences where less accurate tools are commonly used.

After completing all six visits over a three-week period, the subjects completed the study twice more, once under each of the other two treatment conditions.[27]

Reduced AST (aspartate transaminase) levels

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) testing showed that aXivite caused a statistically significant effect on AST (aspartate transaminase) levels post-workout. This indicates that aXivite significantly reduced the amount of muscular damage accrued during exercise.[27]

When researchers parsed the study data using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, they found that aXivite administration caused a significant decline in post-workout AST levels. This is good news because lower AST levels indicate efficient muscle recovery and minimal muscle damage – the less AST in circulation, the more it suggests that the muscles have not undergone significant stress or injury, and are recovering well.[27]

This result indicates a potential mechanism for phenylcapsaicin's ergogenic effect – in general, the more slowly muscle tissue accrues damage, the longer it can work during exercise. This effect can be also explained by the lower velocity loss induced in the phenylcapsaicin group. A lower velocity loss means that the same load is lifted faster, accumulating less fatigue and less muscle damage as a consequence.[28]

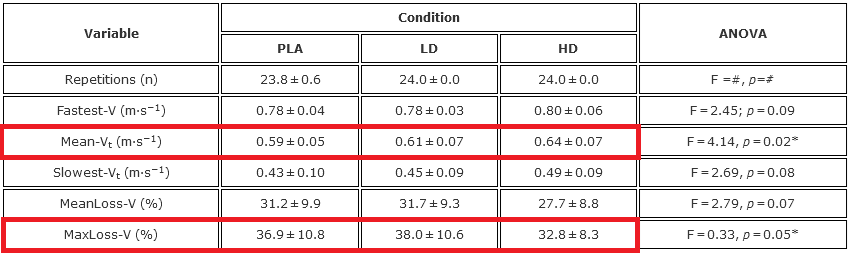

Greater lifting velocity

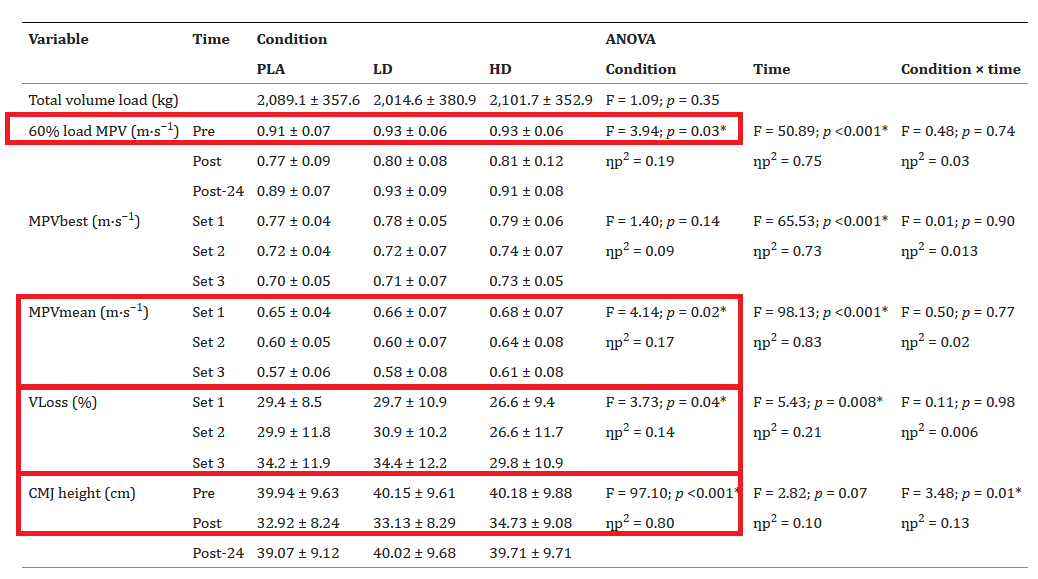

The researchers observed that aXivite caused a statistically significant increase in mean velocity during the 3x8 squat repetitions at 70% 1RM (Mean-V). They also saw that subjects under the aXivite conditions (LD and HD) didn't lose as much velocity as the placebo condition (MaxLoss-V).[27]

Differences were also observed in mean velocity during the squat performance test, as well as velocity loss. This should go a long way towards explaining some of the inconsistency in the literature on capsaicin – most of those studies used 12 mg capsaicin, which is equivalent to 1.5 mg aXivite, a dose that falls well short of the 2.5 mg aXivite used by the HD treatment condition in this study.

Reduced perceived exertion

The HD aXivite condition also caused statistically significant reductions in the rating of perceived exertion for active muscle (RPE-AM), which, in this case, was basically a measure of how fatigued the subjects' quadriceps were during the squat performance test.[27]

The last major finding was that the aXivite HD treatment condition caused a statistically significant reduction in the subjects' average rating of perceived exertion for active muscle (RPE-AM) scores. In context, that means the subjects felt their quadriceps were notably less fatigued during the squat performance test when taking 2.5 mg aXivite.[27] This effect is interesting, because contrary to most ergogenic aids, phenylcapsaicin has a direct impact on peripheral mechanisms modulating the peripheral RPE but not the general RPE in this case. It can be considered as a peripheral analgesic.

There are two important things to note about the results of this study:

The first is that, according to the authors, post-hoc data analysis revealed that only the ergogenic effects of the high-dose treatment condition achieved statistical significance.[27] The second is that, as a corollary, the researchers were unable to verify a dose-response relationship for any of the dependent variables studied.[27]

It would appear from these results that low-dose aXivite (0.625 mg) was not a sufficiently large dose to elicit an ergogenic effect. An important corollary to this is that we wouldn't expect the equivalent capsaicin dose – 5 mg – to do much either.

Perhaps a dose-response relationship would emerge if the HD dose (2.5 mg) were studied in conjunction with a series of higher doses, say 5 mg aXivite and 7.5 mg aXivite.

As the authors of the study point out, higher-dose aXivite's effect on RPE-AM could potentially be explained by the TRPV-1 receptor mechanism of action. That's because, again, neural feedback from the III and IV afferent nerve fibers are a major contributing factor to peripheral fatigue, and hence, exercise-related discomfort and RPE. By the same token, modulating the transmission of these afferents through TRPV-1 activation should decrease RPE.[27]

-

Increases fat oxidation and decreases heart rate during steady-state aerobic exercise (2023)

Now that we know aXivite can improve key metrics of performance and recovery in resistance exercise, it's natural to wonder whether the supplement can improve endurance performance as well, especially given the role that the afferent III and IV type nerve fibers play in the onset of fatigue. It makes intuitive sense that if we can delay the onset of fatigue through TRPV-1 modulation and, hence, the fatigue-inducing firing of afferent type III and IV fibers, then that might translate to a boost in athletic endurance.

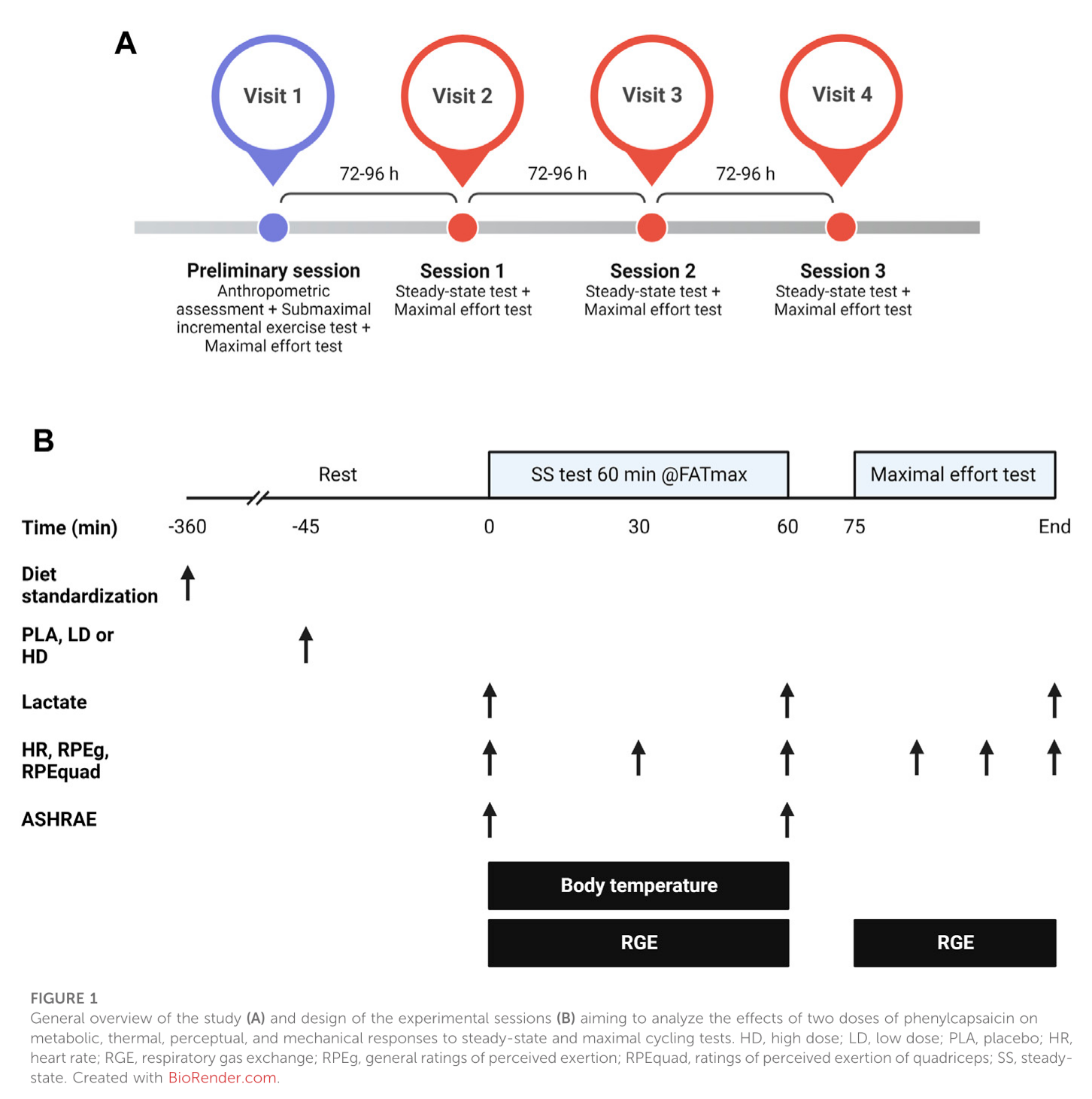

In the second study – also randomized, placebo-controlled, triple-blind – 17 active males with an average age of 25 visited a laboratory on four different occasions, each separated by 72-96 hours.[29]

During the first visit, the participants performed a submaximal exercise test in order to determine their maximal fat oxidation (MFO), the highest rate at which an individual's body can oxidize or burn fat for energy during exercise. A person's MFO occurs at a specific exercise intensity, usually expressed as a percentage of an individual's maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max). Measuring MFO is really important in exercise physiology because in substrate oxidation the lack of this measure bias the standardization of the results. However, many studies in the field are not covering this issue. In our case, one of the authors of the paper, Dr. Amaro-Gahete is also a leading author in the validation of oxidation equations for different populations.

So, we're talking about two separate metrics here:

- The maximum proportion of fat each person is capable of burning during exercise, and

- The exercise intensity at which each participant achieved MFO.[29]

The participants also performed a maximal incremental test, which is designed to measure VO2max, the maximum rate at which an individual can consume oxygen during intense, whole-body exercise. VO2max is widely regarded as the best overall measure of aerobic fitness and cardiovascular endurance, and is typically expressed in milliliters of oxygen consumed per minute per kilogram of body weight (ml/kg/min).

After the preliminary session, the following 3 sessions had the participants ingest either low-dose (LD) aXivite or high-dose (HD) aXivite, 45 minutes before starting:

- a 60-minute steady-state exercise test conducted at each participant's MFO intensity, and

- another maximal incremental test.

This study measured a lot of performance-related variables (we'll cover them all below), but the main purpose was to see whether aXivite phenylcapsaicin administration could increase the proportion of fatty acids oxidized for energy during exercise at FATmax (the intensity level that corresponded with each participant's MFO). Typically this is expressed in terms of a respiratory exchange ratio (RER). The higher a person's RER at any given moment, the more their body is relying on carbohydrates for energy – an RER of 0.7 indicates fat-dominant metabolism, 1.0 indicates reliance on carbs, and values over 1.0 indicate anaerobic respiration. The research team wanted to determine aXivite's impact on fat burning because of previous research suggesting that TRPV1 activation could decrease RER.[30]

In other words, the last 3 sessions differed from the preliminary session only in the administration of aXivite to each participant. The testing protocol was identical in all 4 sessions.

Just like in the previous study, the doses used were 0.625 mg in the LD condition, and 2.5 mg in the HD condition.

The research team went to great lengths to standardize the participants' metabolic state at the beginning of each session – participants were instructed to fast for at least 6 hours beforehand, with their last meal consisting of a drink with exactly 45 grams of maltodextrin and 30 grams of protein powder.[29] They were also told to abstain from intense exercise during the 2 days preceding each laboratory visit, as well as the consumption of any stimulants and supplements for 24 hours beforehand.[29]

Treatment with aXivite did, in fact, increase fat oxidation at different points during the submaximal exercise test, an effect reflected in statistically significant differences in peak fat oxidation (FOpeak) between the treatment conditions.[29]

The study confirmed its main hypothesis, finding that treatment with both LD and HD aXivite did increase fat oxidation during the steady-state submaximal exercise test. This effect was observed both at various increments throughout the testing session, as well as in the participants' observed peak fat oxidation (FOpeak).[29]

Treatment with aXivite also significantly reduced maximum heart rate during the test, which reflects an improvement in cardiovascular efficiency. The authors of the paper speculate that TRPV-1 activation, by increasing the participants mechanical efficiency via ergogenic effects, may have decreased the relative workload experienced by the participants during the test. This would, in theory, translate into a lower demand on their cardiovascular systems.[29]

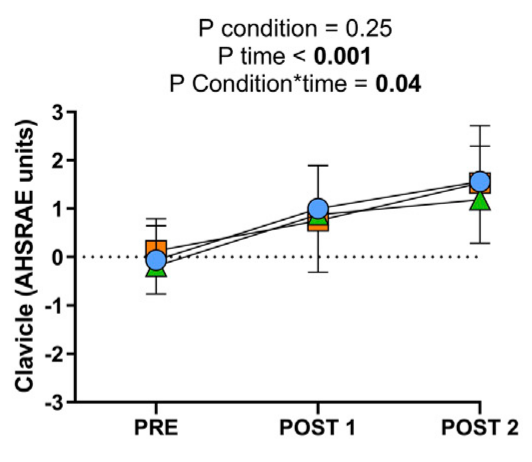

During the incremental test, the HD aXivite condition caused a statistically significant increase in general rating of perceived exertion (RPEg) at 60% of maximum effort.[29]

During the incremental exercise test, the aXivite treatment conditions caused noticeable reductions in rating of perceived exertion at 60% of maximal effort. However, only one of the observations achieved statistical significance – general rating of perceived exertion (RPEg) at 60% maximum effort.

The HD aXivite treatment condition (marked by the green triangle) caused a significant reduction in perceived heat after the maximal exercise test. PRE=before exercise, POST 1=after submaximal test but before incremental test, POST 2=after incremental test.[29]

One of the more unusual things about this study is that the research team had participants report thermal perception, i.e. how hot they felt, using the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) scale. As it turns out, the aXivite HD treatment condition significantly decreased how hot the participants felt in their clavicle area after the incremental test, suggesting that it helped their bodies cope with the rigors of high-intensity exercise.

This is quite an interesting study. Although the researchers observed fairly large between-group differences in many if not most of the variables studied, only a few of these effects achieved statistical significance. Our opinion of this study is that it shows some very promising preliminary data, which should be further investigated by larger follow-up studies. We have a feeling that if this study were repeated with a much larger sample size, which would do away with the need for a crossover design, it would probably find statistical significance in more of the data.

-

Improves lifting velocity and countermovement jump (CMJ) height in multi-exercise workout (2023)

In the third and perhaps most interesting of the studies, 25 trained subjects with an average 1 rep squat max of 125.6 kg were enrolled into a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled experiment.[31] Note, again, that this 1RM works out to 276 pounds, which is nothing crazy, but definitely a lot better than the average, untrained male. Just like the first study, we should consider this an intermediately-trained study population, which gives a little more credence to the observed benefits of aXivite.

Jimenez-Martinez et al. employed a familiar experimental design in the third and final randomized controlled trial we're discussing in this article.[31]

The study design (refer to the inset image) used should look familiar to you by now – it's exactly the same design used by the first study we discussed, with the only changes being the variables measured. For reference, EMG in this image refers to electromyography, basically measuring muscular activity with electrodes, CMJ is countermovement jump, and RM is rep max.

One uncommon element of this design is the use of the isometrics in between the warm up set (1x2 at 60%) and the main squat set (3x8 at 70%). These were performed by having the subjects in a Smith machine poised at exactly 90 degrees of knee flexion on a dynamic floor capable of measuring their downward force production. They executed 2 five-second efforts, separated by one minute of rest, during which the researchers measured the force produced.[31]

None of the mechanical variables measured during the isometrics showed any statistically significant effects between treatment conditions,[31] so we won't be talking any more about the isometric part of the study, but it's interesting to note as a concept.

Nor did the electromyographic responses show any statistically significant inter-group differences,[31] so we won't discuss those either.

However, when it came to the mechanical responses the participants exhibited to aXivite treatment during the squat and CMJ tests, the study uncovered quite a bit:

The squat and CMJ study demonstrated some important effects that were consistent with the findings of the first study.[31]

The study did find that, once again, aXivite treatment had statistically significant benefits when it came to mean propulsive velocity (MPV) and maintenance of velocity (Vloss) during the squat test. Obviously, a higher MPV number is better – it means the participants were able to accelerate the barbell faster during the concentric phase of the squat – but a lower VLoss is better, since it means the participants lost less velocity over the course of each set. That is, a VLoss of 26.6% for set 1 means that by the end of that set, the participant's average MPV was 26.6% lower than it was at the beginning of the set.[31] This also means that participants could have performed more repetitions until achieving muscle failure.

The other big finding was that the participants did much better on the CMJ they performed immediately after the squat test. And look at the p-value on this result – it's practically non-existent, at a value of less than 0.001.[31] This means that it's statistically impossible for this result to have occurred by chance. This result also means that the enhancement of performance also impacted in a reduction of fatigue accumulation, as CMJ is commonly used as a measurement for acute changes in muscle function and fatigue.

Conclusion: Incredible Research Beyond Thermogenesis

The three randomized controlled studies that we discussed in this article strongly suggest that aXivite phenylcapsaicin exerts all the same benefits as ordinary capsaicin, at a much lower dose. In fact, as Jimenez-Martinez et al. point out in the squat-and-CMJ study we discussed last, the magnitude of the effects they observed at 2.5 mg aXivite is consistent with what previous research has reported at 12 mg capsaicin.

Looking for a unique use of aXivite? Both MuscleTech Alpha Test Thermo and Alpha Test Thermo XTR contain 62.5mg -- read about them below!

Thus, we feel pretty confident saying that the core aXivite claim – that it's just as good as capsaicin, with much higher bioavailability – is true. The addition of the phenyl group, and the microencapsulation, appear to work the magic that aXichem claims they should.

The discussion gets more interesting when we start to consider what specific sports nutrition applications aXivite could be good for. What the MPV, VLoss and CMJ metrics used by studies #1 and #3 have in common is that they measure the ability of the muscles to generate accelerative force. This is a very specific, and very important, aspect of athletic endurance. Mean propulsive velocity (MPV) is a reliable proxy for athletic endurance because by measuring the average speed at which an athlete can move a load, it links directly to muscular endurance and cardiovascular efficiency. Higher MPV indicates the ability to maintain consistent force production, which is absolutely essential for endurance activities.

What makes aXivite potentially great for sports is that, put another way, MPV can reflect an athlete's explosive strength and power, which are crucial for quick accelerations and decelerations involved in changing direction. Higher MPV indicates the ability to generate rapid force, which is absolutely for game-winning agility.

CMJ height, on the other hand, measures lower body power and explosive strength. Athletes with greater CMJ height typically possess strong, fast-twitch muscle fibers, enabling them to produce powerful, quick movements necessary for rapid directional changes – which means that aXivite's ability to increase CMJ height is functionally the same as having more fast-twitch fibers. However, the main reason is likely the reduced accumulated fatigue after the squat protocol.

Health and Wellness Applications? Almost Certainly

Of course, the studies we covered in depth only deal with the ergogenic, sports nutrition side of things – there is absolutely no reason to believe that aXivite phenylcapsaicin wouldn't have the same health benefits as ordinary capsaicin as well. We'll be waiting for the studies on that, but given that these RCTs basically show it's a more bioavailable form of capsaicin, you can bet your bottom dollar that they'll have positive results, too.

You can sign up for PricePlow aXivite and See Nutrition news alerts below so that we notify you of new products, articles, studies, and podcasts:

Subscribe to PricePlow's Newsletter and Alerts on These Topics

Supplements with aXivite

If you want to try aXivite on its own, there are currently two supplements that have the ingredient alone:

- Omne Diem Max Reps Elite (direct link) (yields 2.4mg phenylcapsaicin from aXivite in a 4-capsule serving)

- Carotec aXivite (60mg aXivite per capsule)

However, aXivite is also in larger-scale formulas as well:

It's the age old question... pills or powder?! With MuscleTech Burn iQ, you have a tough choice to make - but it's ultimately a win-win.

Industry innovator MuscleTech has been SEE Nutrition's biggest partner with aXivite-based supplements, and they've put it into several products to cover a few different niches:

-

Fat Burning Powder: MuscleTech Burn iQ Powder

MuscleTech grabbed headlines with this formula thanks to its inclusion of caffeine-alternative paraxanthine, but don't forget that there's also aXivite inside too! You get 30 milligrams of aXivite in a full two-scoop serving, helping to support both fat oxidation and performance (as we've seen in this article).

You'll also get solid doses of L-carnitine, L-tyrosine, and taurine to support the brain and body.

Read about it in the link above, or see prices below.

MuscleTech Burn iQ Powder – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

The same goes for their capsule version:

-

Fat Burning Pills: MuscleTech Burn iQ Capsules

While Burn iQ has less material than the powder, it can be conveniently taken as a capsule, providing even more aXivite, with 60 milligrams in a full three-capsule serving.

MuscleTech Burn iQ – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

-

Testosterone Boosting Fat Burners

AlphaTest Thermo burns fat and boosts testosterone, while Alpha Test Thermo XTR with enfinity paraxanthine unlocks next-level results with an even more potent formula! Find your perfect fit for cutting and maximizing gains!

MuscleTech isn't done yet! They also released two versions of their fat-burning testosterone boosters, both of which include aXivite:

Both of these contain 62.5 milligrams of aXivite, the highest-dose of all of the MuscleTech formulas listed above!

You can also see all PricePlow articles mentioning aXivite below:

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)