Dr. Garrett Smith, known as the Nutrition Detective, joins the PricePlow Podcast to discuss his journey into the world of vitamin A toxicity and its connection to numerous health issues. This is an impactful episode, as we're learning how damaging this fat-soluble class of molecules is -- especially when consumed in excess over time -- and how difficult it is to remove from the body.

Is there a Vitamin A Toxicity EPIDEMIC? Dr. Garrett Smith joins the PricePlow Podcast for Episode #150 and dives into the dangers and symptoms of Vitamin A toxicity -- and how to detox it for better overall health. We also get into the dangers of calcification and joint pain from vitamin D3 supplements, making for a very informative and potentially controversial episode.

Dr. Smith is having tremendous success in supporting those who begin restricting and detoxifying vitamin A, relieving numerous health maladies from basic joint pain and skin conditions to reversing kidney, liver, and thyroid diseases. Followers of his program are also having great success in areas of fertility.

Dr. Smith also shares his views on vitamin D supplementation and its potential negative effects, which is how Mike started to follow him in the first place, having noticed that vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplements were contributing to his joint pain. At the end of the episode, Mike explains that he's been restricting vitamin A and D since January 2023, with incredible success.

Vitamin A: An extremely toxic family of molecules in excess

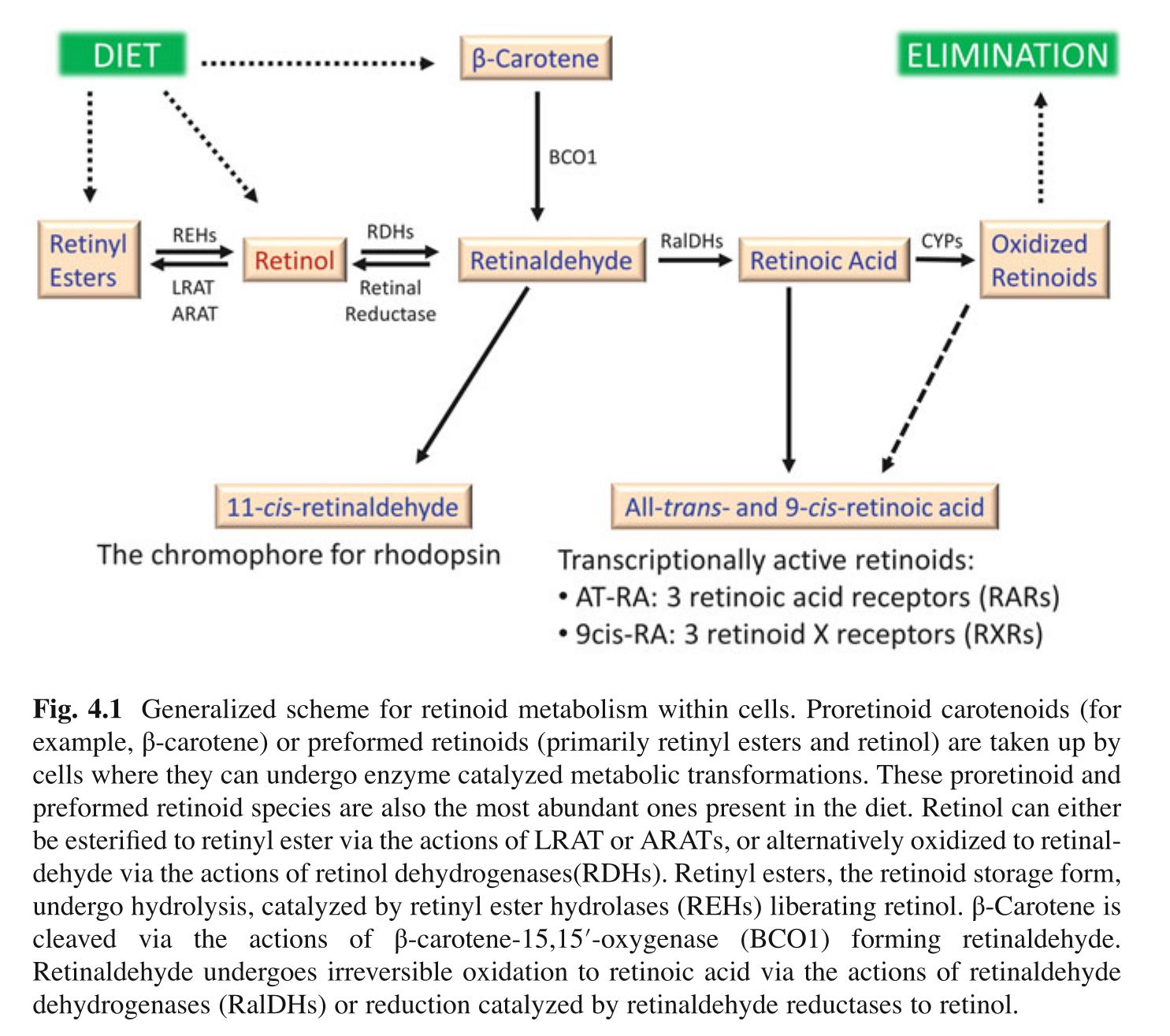

The conversation explores the pathway of vitamin A in the body, from its sources in plants to its conversion into retinaldehyde, retinol, and retinoic acids, and the toxicity of all of these molecules. Dr. Smith also explains the liver's role in filtering toxins and producing bile, as well as the importance of bile in detoxification.

Sadly, there's no commercially-available lab test to determine vitamin A toxicity, since retinol is kept in a tight homeostatic range in the blood and the rest is kept in the liver, but the men discuss ways to determine that you may be having some subclinical issues without getting a dangerous liver biopsy.

Introducing Toxic Bile Theory

The concept of toxic bile theory is introduced, which is a new paradigm/framework on health and disease that explains how countless diseases are caused when toxic bile damages the liver and leaks into the bloodstream.

Low Vitamin A Diet

The low vitamin A diet includes avoiding organ meats, pork, dairy, eggs, and high vitamin A plant foods. Animal protein sources like red meat and poultry are preferred. The diet also includes white or light-colored plant foods, cooked beans, whole grains like oats and barley, and select fruits like bananas, apples, green grapes, and pears.

In the final part of the conversation, Mike and Dr. Garrett Smith discuss their personal experiences and perspectives on nutrition and supplementation. They touch on finding balance, the role of minerals in the body, and the benefits of removing toxins from the body rather than adding more supplements.

Dr. Smith also shares information about his Love Your Liver Program and the testing and consultation services he offers, and he sells an incredible mineral supplement called Keystone Minerals that Mike gives to his family, as well as a very popular topical magnesium lotion.

Subscribe to the PricePlow Podcast on Your Favorite Service (RSS)

https://blog.priceplow.com/podcast/dr-garrett-smith-vitamin-a-toxicity-150

Video: Learn about the Vitamin A Toxicity Epidemic with Dr. Garrett Smith

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:59:11 — 109.1MB)

Detailed Show Notes: Dr. Garrett Smith on Vitamin A Toxicity

-

00:00 - Introductions

Mike and Ben welcome listeners to the PricePlow Podcast and introduce their guest, Dr. Garrett Smith, who Mike has followed for nearly two years now.

Dr. Smith's background is introduced, focusing on his expertise in health, nutrition, and detoxification. He comes from a background of strength training, having begun weight lifting at age 11. This led to nutrition, and he realized how food affected his health.

He was a personal trainer, got a degree in physiology and a minor in chemistry and nutrition. He worked in a supplement store, then headed to naturopath medical school.

Dr. Smith has now been practicing for 18 years, and explains many "phases" that everyone goes through, blaming numerous factors for their diseases (heavy metals, carbs, etc).

The main topic of discussion is revealed: Vitamin A toxicity and its potential effects on health, and how the liver and bile are connected in sickness.

-

03:45 - Discovering Grant Genereux's Work on Vitamin A Toxicity

Dr. Smith mentions a Canadian engineer named Grant Genereux who went through chronic kidney disease, jaundice, and brutally painful eczema. He was heading to dialysis, but then realized that nearly all "eczema foods" were all high in vitamin A! So Grant decided to go on a very low vitamin A diet consisting of just beef/bison, white rice, and beans.

Grant's jaundice, eczema, and kidney disease completely went away once he eradicated vitamin A from his diet. He wrote two books, Poisoning for Profits and Extinguishing the Fires of Hell.

After reading half of Grant's first book, and connecting vitamin A with many of his patient's issues, Dr. Garrett Smith realized that he had to change everything he was doing.

-

06:30 - Reconsidering Vitamin D Supplements (Calcification and Joint Pain)

This wasn't the first time Dr. Smith had reversed course on using a vitamin/supplement/nutrient. He did the same thing with Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) in 2013, after realizing through his patients' hair mineral tests that:

- Vitamin D3 supplements raise calcium levels

- Vitamin D3 supplements lower potassium levels

- Vitamin D3 supplements induce hypothyroidism

Did you know that Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is used as rodenticide (rat poison)? It works through inducing hypervitaminosis, calcifying the organs to death. While the rat poison does this quickly, are we doing it to ourselves slowly with high calcium, vitamin D fortified diets and supplements?

Dr. Smith claims to be "one of the most anti-vitamin D supplement people out there". He doesn't think it's good for people.

He states, if you have a lot of pain:

- Get off of the vitamin A supplements

- Get off of the vitamin D supplements

- Stop eating nightshades (which also contain calcitriol, the active vitamin D)

Give the above three a chance for a month and watch pain go down.

Knowing that our listeners may be caught off guard hearing that vitamin D is toxic, Ben asks Dr. Smith to rewind a bit and go deeper.

While we do need sunlight and ultraviolet light, do we know that it's through oxidized cholesterol as cholecalciferol? People have been sold an assumption about this, and it doesn't pan out in the research when you just give cholecalciferol to unhealthy people.

Vitamin D raises the calcium levels in the blood. It either increases calcium absorption from the gut, or it's going to take it out of your bones. Men have been shown to have lower bone density after 3 years of vitamin D supplementation.[1]

Vitamin D overdose induces hypercalcaemia.[2-10] He instructs everyone to look up Vitamin D bone resorption. Ultimately, if you're stiff in your joints, cracking/popping, increase magnesium (the anti-calcium) and remove vitamin D3. Think about it: X-rays look for calcium. Mammograms look for calcium. Calcification is a problem - most diseases involve it.

Calcified Tissue International?!

Hilariously, while looking for citations in these show notes, we found a paper titled "Is high dose vitamin D harmful?" that is published in a journal literally titled "Calcified Tissue International".[11]

Dr. Smith isn't into ingesting fat-soluble (fat-storable) vitamins and/or metabolites. We should let the body control metabolite production.

So getting patients -- and himself -- off of vitamin D started helping everyone feel better. He tells a personal story about how he became constipated from his over-dosing of vitamin D.

The whole point is that this was a mea culpa where Dr. Smith had to reverse course, and it wouldn't be his last.

-

15:00 - Improving Health with a Low Vitamin A Diet

Back to Grant Genereux's work, despite being a doctor, Dr. Smith was still having issues with BPH (benign prostatic hyperplasia -- enlargement of the prostate gland), insomnia, lower back pain, and a bit of psoriasis. Urinary and prostate issues at age 25 were certainly concerning given the fact that his dad had died of prostate cancer.

After taking vitamin A out of his diet (but not to the extreme that Grant goes), avoiding eating liver at all costs, and stopping vitamin A / beta-carotene supplements, his health began to greatly improve. And so did his patients who also followed this recommendation.

Fast forward to 2024, Dr. Smith has been restricting vitamin A consumption for six years, and Grant recently celebrated ten years with extremely little vitamin A consumption.

The onslaught of vitamin A is fierce. We get it from:

- Cosmetics

- Supplements (beta-carotene, cod liver oil, liver pills)

- "Eat the rainbow"

- Eggs

- Dairy

Note: Mike will later point out some of the data on beta-carotene, cod liver oil supplementation, and heavy egg consumption that shows a lot of increased disease.

The toxicity can get handed down via pregnancy. The more toxic someone becomes, the slower their detoxification is. One thing not mentioned here that we missed is how glyphosate slows retinoid metabolism as well![12-14]

-

19:30 - Vitamin A and Carotenoids

Ben gets to interject and ask a bit more about Vitamin D, but also asks a general question -- are all carotenoids bad?

Dr. Smith first says that there is no such thing as a zero vitamin A diet. It would be too unhealthy, there are just not enough foods and they'd have no other nutrition. He doesn't think carotenoids are necessary, he's not convinced it's essential. FDA doesn't really support any health claims with them.

In general, it's just a math problem -- we want the amount we're ingesting to be less than the amount we're excreting.

Dr. Smith will later state that there is no animal-based vitamin A in the world without carotenoids first. Provitamin A carotenoids (beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin) are the precursors.

-

23:15 - More on Vitamin D, Sunshine, and Health Effects

Back to vitamin D, another general issue: are studies talking about levels, or are they talking about cholecalciferol consumption? Dr. Smith agrees that someone with higher vitamin D levels and isn't supplementing will have better health.

However, there are numerous reviews showing that vitamin D supplementation doesn't have that many net benefits and the research shows unconvincing, mixed results, with very little in terms of outcomes in terms of bone mineral density, fractures, mortality, and disease.[1,8,11,15-24] For instance, higher blood vitamin D levels often leads to lower bone mineral density,[20,24] contrary to popular belief.

Those who eat carotenoids have been known to turn orange,[25-27] and liposuction patients who try to "eat healthy" have fat that looks orange. There are also recently-discovered genetic conditions that could make hypercalcaemia worse.[28,29]

What does sunshine do? Dr. Smith claims that it oxidizes vitamin A, and that his patients get less sunburnt over time.

Vitamin A and D are also antagonistic to each other.[30] So are we "vitamin D deficient", or are we really vitamin A toxic?!

But the big issue is when we start supplementing metabolites. These are fat-soluble, fat-storable molecules! More is not better. The liver is forced to store these!

He then makes fun of a prominent doctor (Dr. Ken Berry) who said that the liver doesn't store toxins,[31] which is verifiably false and has been known for a very long time.[32-34]

-

27:45 - What is Vitamin A? The Biochemistry of Vitamin A and Carotenoids

Mike notes that the FDA allows for a lot of things to be labeled as Vitamin A:[35,36]

- Beta-Carotene / β-carotene

- Alpha-Carotene / α-Carotene

- β-cryptoxanthin

- Retinol / all-trans-Retinol / "Vitamin A"

- Retinaldehyde / "retinal" / all-trans-retinal / vitamin A aldehyde

- Retinoic acid / tretinoin / all-trans-retinoic acid / Vitamin A acid / (sold as Retin-A)

- 13-cis-Retinoic acid / Isotretinoin / (sold as Accutane)

- 9-cis-retinoic acid / Alitretinoin / (sold as Panretin, used in chemotherapy)

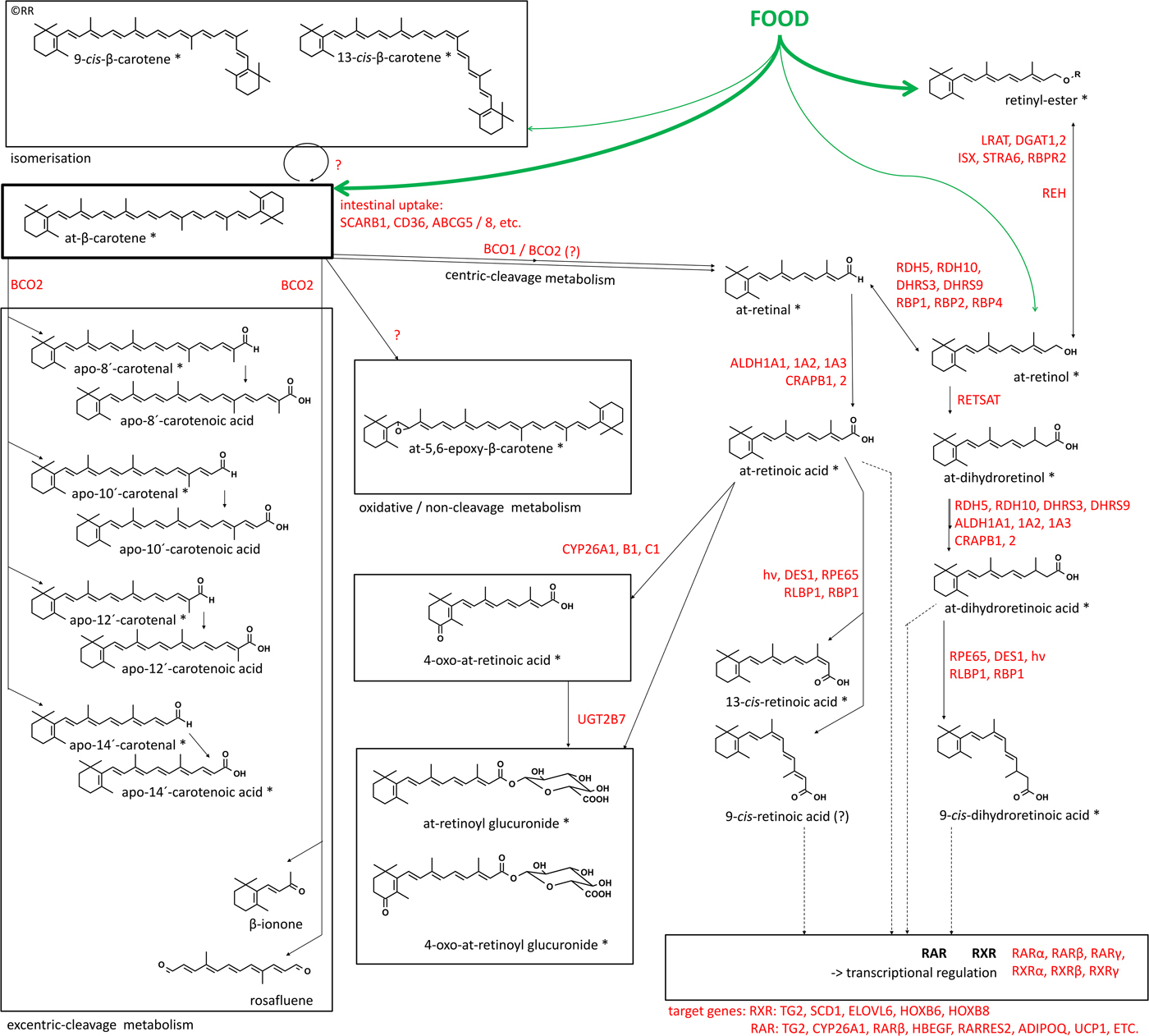

The first three, beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin are the "plant vitamin A" -- these are provitamin A molecules that get converted into retinaldehyde, which gets converted into retinol, what we really consider vitamin A.[32,37-39]

Note that beta-carotene, the most prominent provitamin A carotenoid, gets converted into two retinaldehyde molecules.[40,41] Further, the scientific community often hides the retinaldehyde's molecule's identity as a toxic aldehyde by calling it "retinal".

"There is no vitamin A anywhere -- animal, retinol, retinoic acid -- without carotenoids first."

Other similar molecules, like lutein and zeaxanthin are not provitamin A -- they don't break down into retinaldehyde, although they do activate the "retinoic acid receptor", or RAR.[42]

Dr. Smith doesn't like the term "retinoic acid receptor" though, because it can be stimulated by many compounds, not just retinoids and carotenoids.[43] It can even be stimulated by nothing![44] There are over 7500 retinoic acid receptor agonists - a very promiscuous receptor.

Back to beta-carotene, it gets chopped into two retinaldehyde molecules -- and anyone who knows nutrition knows that aldehydes are not good for us (acetaldehydes cause hangovers, formaldehyde, etc). It can go backwards into retinol, or forwards into retinoic acid:[39]

Retinol gets stored in the liver fat as retinyl esters. Why? To get it out of the blood. If you have too much in the blood, free retinol is known to be extremely toxic. It's stored because we can't get rid of it fast enough.

Then you get into the retinoic acids, which can be excreted in various ways:[45]

- Retinoic acid / tretinoin / all-trans-retinoic acid / Vitamin A acid / (sold as Retin-A)

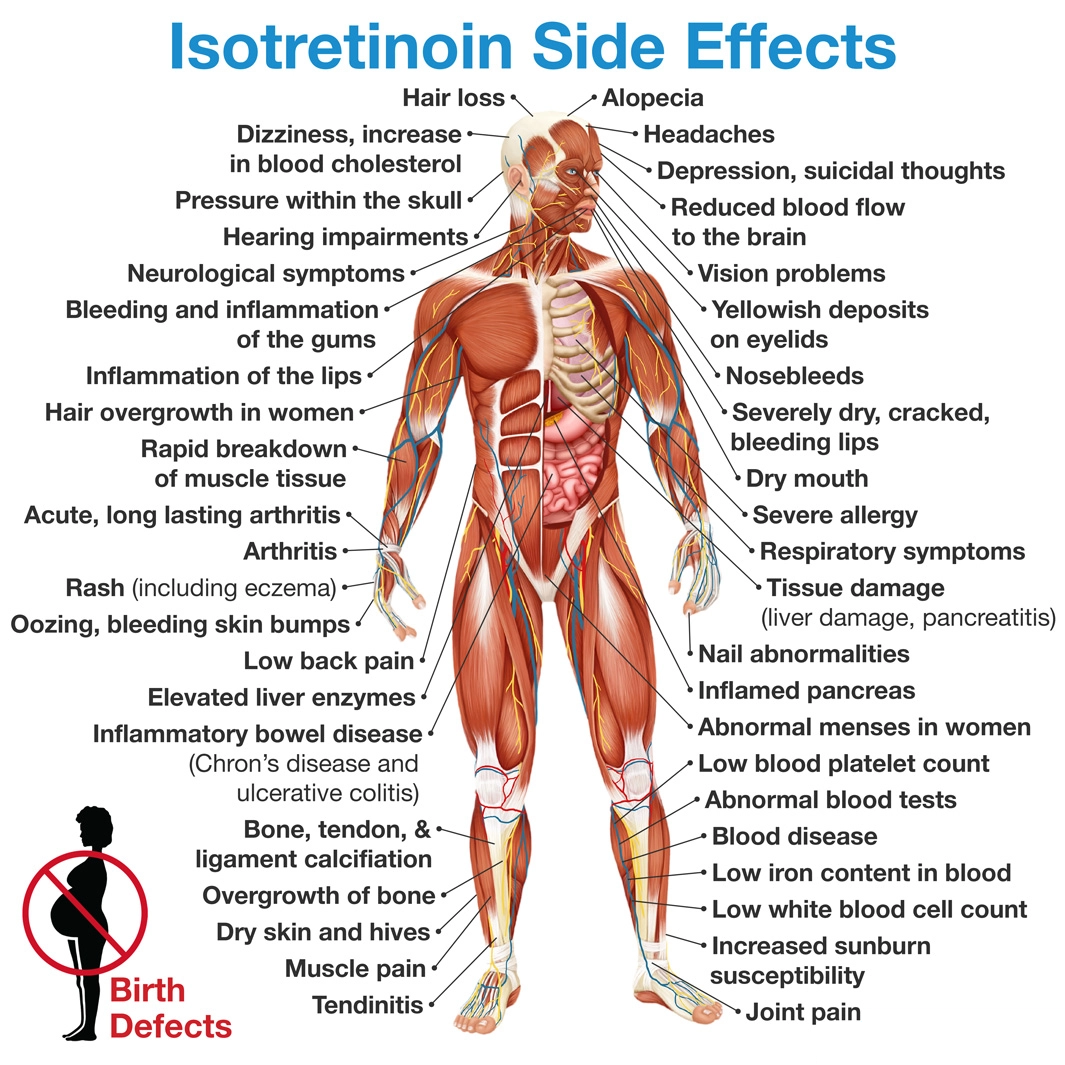

- 13-cis-Retinoic acid / Isotretinoin / (sold as Accutane)

- 9-cis-retinoic acid / Alitretinoin / (sold as Panretin, used in chemotherapy[46])

Below is a more detailed image:[45]

If you ever hear the list of accutane side effects, it's downright awful, ranging from IBS[47-49] to headaches[48-50] to depression,[47,51,52] to suicide ideation and attempts![47,51,53-55] It also causes horrific birth defects (teratogenic).[47,56-59]

Retin-A isn't much better, with studies showing significantly increased mortality![60,61]

And if you eat beta-carotene, you do get elevated levels of 13-cis-Retinoic acid / Isotretinoin / Accutane.[45,62]

Taking Retin-A and Accutane are such disasters because they're metabolites -- like vitamin D3 supplementation, ingesting metabolites forces the body to deal with something it would have previously had control over.

-

35:15 - Retinoic Acid Toxicity - A Deadly Chemical Peel

Dr. Smith explains how toxic retinoic acids are -- they are used as chemical peels, dissolving the top layers of skin. These are actually called "controlled wounds" for the skin![63] It's dissolving cells. It comes out of the bile in your food, and causes tons of the intestinal problems we talk about -- leaky gut, for instance.

When you ingest the food, the retinoic acid you metabolize will inhibit the amount of future retinoic acid produced in the body.[64] This is a cautious, negative feedback loop. While this does slow down detox, it protects you from further toxicity.

But if you take retinoic acid as a medicine directly, you override that feedback loop. And you can get stuck here without a lot of work. For example, Dr. Smith sees patients who have had dry eyes from Accutane for thirty years.

Then there's the big veteran's study, giving them Retin-A for their faces. They shut the study down because so many veterans were dying![60] And they had already filtered out the veterans who thought they were going to die.

You can absolutely get vitamin A toxic through the skin.

Ben then asks about how much Accutane gets created when eating vitamin A foods, Mike points to the two metabolic studies cited above.[45,62]

By taking retinoic acids, your body cannot send it backwards (see the pathway maps above), so all it can do is slow down the ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase) enzyme that would create more of it. But this slows down all detoxification!

-

41:30 – Assessing Vitamin A Toxicity, a Scientific Catch-22

The two commercial lab tests available to us are serum vitamin A and retinol binding protein 4 (RBP-4, what binds to vitamin A), but these do not indicate toxicity! Serum retinol is kept in a tight homeostatic range,[65-69] and RBP-4 follows with it (and sometimes goes down if your zinc and protein levels are too low).

The only way to truly assess toxicity is a liver biopsy[65,70] or radioactive tracers[71-73] - most people don't want to do either of these. The vitamin A simply stays in your liver, where routine blood tests won't detect it.

Dr. Smith mentions a case study where a patient had liver problems, his serum retinol was only 17 or 18 (anything under 20 is considered "vitamin A deficiency"), so his doctors ordered a liver biopsy and his liver stores were through the roof.[74] They gave him a "normal diet" and he was able to normalize serum retinol and RBP and begin mobilizing it again. The doctors also point out that protein deficiency was also holding him back.[74]

Serum retinol is simply not good to test.

-

45:15 - What is the Liver, and What is Bile?

Dr. Smith claims that this is the most overlooked part of medicine. Many people think of it as a sort of "detox organ". The liver definitely makes tons of proteins, but that's not the goal of this conversation.

- The liver is a filter. By definition, a filter takes something out of something else, and the liver does exactly that. It takes stuff out of the blood.

- The liver is a sewage processing plant. It takes compounds and turns them into other compounds.

Those compounds are not always less toxic, though. Sometimes, through biotransformation, it creates compounds that are further intoxifying (common example being acetaldehyde being more toxic than alcohol when you drink).

- The liver stores endproducts, at least until they can be disposed of. In the research, you'll see the word "accumulate", not "store".

The above three points are Dr. Smith's concerns in terms of liver function and health.

So how does the liver excrete the processed and stored end products? It puts them into the bile. People seem to think that the liver makes things "magically disappear", but it needs to be removed -- often via urine, stool, sweat, etc. Using the skin as a detox organ can be quite damaging.

The bile is the most toxic fluid in your body[75] - it's how your liver gets rid of its waste. Your liver poops bile into the intestines, you need to poop that all out in your stool. But around 95% of bile acids recirculate back to the liver.[76]

Since you can't get rid of 100% of toxins right away, it's paramount that you stop ingesting toxins in the first place.

-

50:00 - Toxic Bile Theory

This brings us to "toxic bile theory", a term that Dr. Smith coined to describe a new paradigm on health and disease.

Not mentioned in the podcast, but this was originally pioneered by a researcher named Anthony Mawson who published several papers, connecting modern diseases to bile "spillover" from the liver into the serum, from flu to glioma to gulf war syndrome to rubella to the disease state known as "COVID".[77-81] He actually first made the connection in 2009 when looking at chronic aggression and low resting heart rate from retinoid toxicity.[82]

In general, toxic bile theory states that when the liver becomes cholestatic (cholestasis is a condition where the flow of bile from the liver to the duodenum is impaired), the bile ducts get damaged and the bile begins to "spill over" into the bloodstream. This liver damage is often (but not always) caused by excess retinol stores, but can also be from copper toxicity, vaccine injury, and several other things like excess fructose and/or seed oil metabolites (more toxic aldehydes).

Vitamin A toxicity has been shown to cause cholestasis.[83]

So if you're in this state, and bile is flowing where it should not be, leading to the various manifestations of vitamin A toxicity (headaches, joint problems, fatigue, skin conditions, etc.. more are described below), then what do you do?

- Facilitate removal

- Provide nutrients (particularly minerals) to help protect itself and run detoxification

The above two are the basis of what Dr. Smith works on.

As an example that affects many people, bile acids that spill into the gut are connected to GERD and other gut disorders.[84,85]

Mike backs things up to make sure it's all clear, and the guys dig a bit deeper into bile and stool. One manifestation of cholestasis is constipation. Dr. Smith discusses a study where constipated individuals have less bile in their stool than normal, who have less than those with diarrhea.[86]

Having less bile coming out makes it more concentrated, making for a terrible negative feedback loop.

-

55:45 - How to Generally Fix the Problem

So how do we turn that negative feedback loop into a positive one?

- Stop putting the toxins in. Stop intoxing before you worry about detox.

The biggest debate is what is a toxin. Dr. Smith clearly believes is that the fat soluble vitamin A family is a main culprit.

- Start supporting removal

Dr. Smith likes soluble fiber, but you have to watch your amounts, start slowly, and use ones that agree with you. He likes psyllium husk, SunFiber, beta-glucan, apple pectin, beans, oats, barley.

Research shows that apples are the healthiest fruit -- it has a white flesh, not yellow, low in vitamin A, and the pectin is very beneficial. It's a bold claim, but there happens to be a ton of research on apples.[87-99]

Activated charcoal is also a big part of Dr. Smith's program, and we joke that it's basically completely unknown in America, while Europeans know it quite well. It's a great detox ingredient with several benefits.[100,101] Charcoal soaks up bile,[102] but doesn't trigger more bile, so taking too much can lead to constipation.

Preferably, we detox through the stool. But if toxic bile gets into the bloodstream, the kidneys get hit next (this is what caused Grant Genereux's problems), and after that, it's generally the skin.

- Stop putting the toxins in. Stop intoxing before you worry about detox.

-

1:02:15 - Vitamin A Toxicity and Subclinical Vitamin A Toxicity Symptoms

Since we're not going to get a liver biopsy to determine vitamin A toxicity, how do you know if you're potentially toxic or subclinically toxic? Mike asks this, segueing from the skin discussion above, since skin problems are most common.

Once you understand toxic bile theory above, you realize that the symptoms could be anything. However, skin issues, gut issues, and eye issues are the most common signs of vitamin A toxicity. There's also anxiety, depression, and lethargy.

The best overall chart of symptoms is actually to look at the list of accutane side effects,[47] shown on this image:

"Overs" vs. "Unders"

People generally get overweight and insulin resistant, but there are some people who get very underweight. The latter of these two -- chronically underweight -- is actually worse. You will see these two patterns on lab tests, too. Dr. Smith calls the people who run high as "overs", and the people who run low/underweight as "unders". 95% of the people he sees are overs.

LDL cholesterol -- the "bad cholesterol" -- carries retinol.[32,103,104] Dr. Smith sees that LDL is often high on vitamin A toxic individuals, and the research shows that LDL (low density lipoproteins) are forced to carry retinol when RBP-4 production breaks down.[103,104] This has been known for over 50 years: LDL does a very poor job of retinol transport compared to RBP-4, leading to highly damaging effects from these poorly-bound retinyl esters.

Triglycerides also go up when high vitamin A is given to animals or humans.[105-108] Note that Accutane also causes triglycerides to go up.[109,110] Take it away and it goes back down.

Then there are the commonly-measured liver enzymes, ALT, AST, GGT, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Yet these numbers don't always manifest even when there are liver function problems. Researchers and doctors call this "silent liver disease".[111]

Note: Later on, at the 1:11:15 mark, Dr. Smith also mentions that high serum bile acids and bilirubin are good indicators of toxicity states.

People who were born jaundiced (roughly 60-80% of babies nowadays![112]) have a lot of liver problems, Dr. Smith states that this is very often vitamin A toxicity. Mike mentions that he had heard this on Smith's Nutrition Detective Livestreams on YouTube, relating a personal story and how this revelation was a foundational learning moment in his life.

But a jaundiced baby isn't a death sentence, it just means you started from behind -- it can be fixed.

Skin color changes are also signs of vitamin A toxicity. Mike jokes about the well-known case study, "Carrot Man",[26] which describes a man with carotenemia.[27] This also happens in Zambia, a country that is over-fortified with vitamin A -- the children turn orange during mango season.[113]

Once the skin turns orange, the research indicates that this is basically hypervitaminosis A.[113]

-

1:08:30 - Who is Most Harmed by Vitamin A? (Slow ALDH, Accutane / Retin-A Survivors)

Men detox faster than women. Men don't make body fat as easily -- women are better at storing toxicity, and they make less bile,[114] so they detox slower and have a tougher time with this.

Genetically, 50% of Asians have slower ALDH (aldehyde dehydrogenase),[115] the enzyme that breaks down aldehydes and moves the process along. This is why they get flushed when drinking alcohol -- ALDH metabolizes acetaldehyde (alcohol's toxic byproduct) as well as retinaldehyde.[45,115] When faced with this genetic issue, Asians who drink build up more acetaldehyde faster.

So anyone with impaired ALDH is going to have a tough time recovering from vitamin A toxicity or excess beta-carotene consumption.

Smith comments that the traditional Asian diet has almost no vitamin A!

Additionally, those who have been damaged by the medications Retin-A (retinoic acid / tretinoin / all-trans-retinoic acid) and Accutane (13-cis-retinoic acid / isotretinoin) are also worse off.

When talking about blood tests, the reference ranges are based on averages in the human population. So if there's a population-wide toxicity problem, most are within the range. Dr. Smith has also been watching reference ranges shift from Labcorp over the years! It's simply based on statistics -- but there's a sick population.

-

1:12:45 - What's in the Low Vitamin A Diet?

OK, so orange carrots, sweet potatoes, and egg yolks are out. Mike then tasks, what's allowed?

Dr. Smith notes that he has an entire livestream on this in his Love Your Liver program. He hits on the basics with regards to vitamin A here:

- NO organ meats! (liver and kidney - no filter organs)

- No egg yolks

- No dairy, especially no fortified dairy

With regards to milk, Dr. Smith theorizes that the pasteurized milk has been cooked and the retinol has been converted into worse molecules, such as retinaldehyde (we need to lab test this). So they add even more vitamin A to it!

- No pork - there's so much vitamin A in pork that they called it "lard factor" before they knew what it was![116-121]

In fact, lard factor is named as a synonym for retinol in PubChem.[122]

Pork also has a terrible fatty acid profile and is low in leucine - Ben comments that "pigs are the bottom feeders of the farm".

Mike references the famous Pulp Fiction scene, "Pigs are filthy animals":

- No red, orange, yellow, or dark green edible plant parts.

For plants, consider the part you eat. For instance, bananas are OK because you don't eat the highly yellow peel.

- No soybeans or peas The beans enjoyed are generally well-cooked beans you can tolerate (pinto beans, black beans, and white beans are often popular in the Love Your Liver Program).

So what can you eat?

The good protein sources are red meat and poultry. There's plenty of protein to be had from red meat, turkey, and chicken -- and those who can tolerate beans can get a bit there too.

For fruits, consider those with white / off-white / light green flesh. So apples, bananas, peeled cucumbers, green grapes, pears, etc are good.

Oats and barley are popular as grains, but there are many others.

In terms of bread, don't eat fortified bread -- but you can get unfortified, organic flour and make sourdough, it may be good. But if you're sensitive to gluten, don't eat it yet!

On the note of gluten intolerance...

Is gluten intolerance really just vitamin A toxicity? Researchers could not create a cellular model of celiac disease until they added retinoic acid![123]

To align with Dr. Smith's Toxic Bile Theory, he states that celiacs dump more bile than normal controls when they ingest gluten.[124] There are numerous other studies connecting bile acid problems with celiac disease,[124-134] and bile has retinoic acid in it.[66,135] Retinoic acid -- a skin peel[63] -- destroys the cells of the gut!

Mike's bringing sandwiches back!

So Dr. Smith sees those with gluten intolerance get better. He references one of Mike's Twitter threads, where he ranted about bringing sandwiches back.[136] After living various forms of low-carb for over a decade, it's so nice to work in a dietary paradigm where you can actually eat high-quality bread with little to no consequences after enough time in the program!!

-

1:24:00 - Can Successful Dieters Bring Some Vitamin A Back?

Ben asks if you can eventually get some of these foods back. Dr. Smith states that he'll never tell anyone what to do, and it's reasonable if someone wants to go have a blast on their birthday and eat all the taboo foods.

What the low-A community is seeing (using chiropractor Dr. Steve Goedecke as an example) is that after years of toxin removal, it becomes harder to feel alcohol -- the healing liver, with its improved ADH and ALDH pathways, can handle it so much better.

After some improvement, you then can add things back in, but you'll know your symptoms and they'll come creeping back.

Mike tells some of his story: He's been a low vitamin A dieter for 20 months since he stopped taking vitamin D3 after seeing a Tweet from Dr. Smith about getting "calcified into a statue"[137] and then just jumped all-in basically a day later. He mentions that he does not miss eggs whatsoever, but plans to get his serum retinol levels low enough that he can tinker with adding back butter and watermelon, two things he does miss.

This brings us to the egg discussion:

1:31:30 - The Problem with Eggs

Dr. Smith comments that Mike is not the first person to lose all interest in eggs. We then get on the topic of eggs, which is obviously a nutrition hot-button. From the perspective of vitamin A toxicity, eggs have a lot of retinol, lutein, and choline.

Choline is necessary to run the enzyme that stores vitamin A, known as LRAT (Lecithin:Retinol Acyltransferase).[138,139] Egg yolks are often the highest source of a form of choline known as lysophosphatidylcholine, which increases beta-carotene accumulation and increases the cleavage of intestinally-absorbed beta-carotene into vitamin A.[140]

Put together, eggs greatly increase the absorption of vitamin A by as much as 8x![141] They're basically the perfect "vitamin A delivery system to the liver".

The data showing hazard when eating multiple eggs daily

Dr. Smith doesn't go over all of the negative research of eggs, but it's worth sharing here:

An umbrella review admits that most of the egg data is poorly standardized,[142] but the highest-quality data shows the general increase in heart disease once egg consumption is "high" (1 or more egg per day).[143]

1 egg per day or more is where the disease data really starts adding up:

- Increased Fatty Liver[144,145]

- Worse Metabolic Syndrome[146]

- Increased Diabetes and Mortality from Diabetes[147,148]

- Increased Heart Failure and Worsened Heart Disease[143,149-152]

- Cancer and Cancer Mortality[153-155]

- Yolks vs. Whites: Higher Cancer and Mortality in Whole Eggs[155]

- Eczema and Allergies[156,157]

The studies above are from around the world, with several from USA as well as Iran, China, Japan, and Greece.

-

1:32:45 - What About Herbs? (Less is More)

Dr. Smith mentions that in America, we're in the mindset of more more more, but argues that we do better through removal these days.

For example, you don't have an herb deficiency. Most pharmaceutical drugs are based on herbs that have been tweaked. Dr. Smith argues that they all have side effects, but have compounds that force the body to do something it couldn't do or didn't want to do, likening them to weak drugs. But they don't solve problems - removing the herb brings back the problem.

-

1:35:00 - Minerals: What's Good, What's Necessary, What's Bad?

Dr. Smith argues that the list of truly essential minerals is much smaller than most realize. He argues against many of these "trace minerals" that are rare earth elements or radioactive materials.

If you're bragging about an ingredient with 72 minerals in it, you're likely including toxic ones like mercury, cadmium, lead... we've even seen rare earth elements like lanthanum and neodymium on labels - things that the body does not need.

The Three Electrolytes

First, the three electrolytes to ensure proper intake of:

- Sodium - Smith wants as pure of sodium chloride as possible. He uses Jacobsen Salt. Go by taste, but over-salting food is definitely a problem for people. On the other end, when Dr. Smith has patients that don't get better no matter what they do, they're often too low on sodium.

- Potassium - Amazing when done correctly. Bananas, coconut water, maybe some potatoes on occasion. There are several potassium supplements, but be careful -- too much can make your heart do funky things.

Fixing potassium is the quickest way for most people to feel better on a day-to-day basis.

- Magnesium - Smith prefers topical magnesium, he sees it increases magnesium levels on hair mineral tests 10 times better than oral magnesium. He sells Nutrition Detective Magnesium Lotion, which also has a dash of lactoferrin inside.

The "Big Minerals"

- Zinc - Dr. Smith has tried many forms, nothing works as well as zinc picolinate. He sells Nutrition Detective Zinc Picolinate that comes in 15 milligram doses. He's also working on zinc nicotinate (zinc bound to nicotinic acid / niacin), which is now in the 60 capsule version of his Nutrition Detective Keystone Minerals. Zinc helps with basically everything.

- Selenium - Very important for the thyroid and testosterone.

- Molybdenum - Necessary to run sulfur detox, xanthine oxidase (preventing gout and processing caffeine), and you need it to run ALDH. If you have bad hangovers or get sulfur-smelling gas, that may be a sign that you need more molybdenum.

Molybdenum deficiency may also be related to iron overload and iron deficiency.

-

1:40:30 - Mike's Vitamin A and The Ferritin / Vitamin D3 Story

In Episode #144 with Dom Kuza, Mike mentioned that he had high ferritin levels (his blood work is shared publicly online).[158] As an update since then, a single blood donation improved joint health tremendously![159] Removing vitamin A & D improved joints a great amount, but this was yet another "level up".

Dr. Smith was surprised that a single blood donation did so well -- often patients need to get their ferritin down far more than that to yield such great benefits.

Mike's going to stick with this program for the time being, trying to see what may naturally lower SHBG to the point where free testosterone can go up. His pattern of good total testosterone, high SHGB, and low free testosterone is something that nobody really solves without prescription chemistry.

Is ferritin a piece of the puzzle? We're not sure, but there is recent research showing that a mere 8 weeks of vitamin D3 increases ferritin levels.[160] So what happened in the 520 weeks that Mike used high-dose D3?! Mike notes that other long-term vitamin D3 / cholecalciferol users have been in touch with him, also noting high ferritin!

Mike notes that people won't like hearing that vitamin D3 is poison, but if there's an alternative through sunshine and UV lamps that do not lead to D3's side effects, why not use them?!

Ultimately, it's odd that we've become the "biohackers" by taking less stuff at this point.

1:43:30 - PricePlow's Vitamin A / Beta-Carotene Problem

Mike notes that when the writing team started looking at the vitamin A toxicity in late 2022 / early 2023, we noted that we never really did have anything great to say about it in previous blog posts.

Mike then discusses how, when writing the original version of PricePlow in 2008, he wrote the following on the beta-carotene page:

"DO NOT TAKE BETA-CAROTENE IF YOU ARE A SMOKER!"[161]

This was because of a meta-analysis published that same year that concluded that beta-carotene in multivitamins increased lung cancer risk in smokers.[162] Fast forward to early 2023, when we started digging into vitamin A toxicity, and found numerous additional studies with respect to smoking and beta-carotene.[162-167]

But worse, beta-carotene has now been repeatedly shown to increase mortality, cancer, fractures, heart disease, and blood pressure in non-smokers![168-176] We even found a study that had to stop beta-carotene supplementation before the trial was supposed to end because there were so many deaths![177]

But now, we see tons of supplements using high-dose beta-carotene for "natural coloring", and per the FDA, "Vitamin A and C are no longer required on the label since deficiencies of these vitamins are rare today."[178,179]

Mike explains that he's sticking with this until he at least gets to a "deficiency" status (serum retinol level under µg/dL, wondering if free testosterone may be impacted by this and/or the reduction in ferritin.

-

1:48:30 - Beware Fat Soluble Alcohols

Garrett points out how the media often uses beta-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E to attack supplements, since there's so much research showing harm with them.

He points out that vitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin E are all fat soluble alcohols. He adds that vitamin E increases vitamin A absorption by 10x,[180] making it problematic as well. CBD can similarly increase vitamin A in the liver in animal studies.[181]

-

1:49:30 - Look into Lactoferrin and Niacin

On the other hand, Dr. Smith is a huge fan of lactoferrin -- it can help fix leaky bile ducts.[182] He has the Nutrition Detective Lactoferrin supplement. He also likes flush niacin (as nicotinic acid) a lot, as it's an NAD+ precursor to help support the ALDH detox pathway.

On the topic of niacin, Mike noted that when the FDA was attempting to ban NMN (another NAD+ precursor), he had just started listening to Dr. Smith talking about ALDH, and made the connection that the FDA was once again attacking something that could safely support the liver, which was very suspicious.

Dr. Smith notes that NMN is easier to attack because it's newer, but niacin has been around forever. Mike even shows that it's GRAS per the FDA, and has been for 65 years.[183-186]

He is also sometimes keen to use Vitamin K (specifically K2 MK4) in certain cases, such as when there's bleeding gums. Interestingly, vitamin A depletes vitamin K levels![187,188] So those who are on K2 supplements shouldn't have to stay on it forever if they get vitamin A under control.

-

1:52:15 - Getting Help from Dr. Smith and His Team

Dr. Smith has a consultation page on NutritionDetective.com where they give hair/mineral tests, do select blood tests, and you get access to a practitioner as well as office hours access to Dr. Smith himself. Everyone gets 6 months of support.

There are links below to follow Dr. Smith and join his Love Your Liver Program, which is their do-it-yourself program. He also has a free course at MadnessOfModernNutrition.com.

When talking about social media, Dr. Smith mentions that he spends most of his time on Twitter (@NutriDetect), and Mike comments that he likes it best for sharing research. For example, learning about vitamin D3 raising ferritin levels[160] from someone replying to one of his comments.[189]

Limescale and Rust Theory

On that topic, Dr. Smith mentions that vitamin A has been shown to increase iron absorption, although the mechanism isn't fully understood.[190,191]

He used to practice a theory called "Limestone and Rust" -- calcifying and rusting from high calcium and high iron go together. And now he focuses on vitamin A and copper toxicity. But seeing vitamin D increase ferritin, vitamin A increase ferritin... all of these things start to fit together.

"We're doing too much -- Just do less". We're at the point where there's more benefit to less toxins in than forcing more nutrients. More doesn't always make it better, but don't ever go low protein.

Where to Follow Dr. Garrett Smith (@NutriDetect on Twitter)

- Nutrition Detective Supplements on PricePlow

- @NutriDetect on Twitter

- NutritionDetective.com

- Love Your Liver Program

Thank you very much to Dr. Smith for spending the time to educate our audience, this is definitely one of our best episodes ever, if not the best in terms of impact.

Nutrition Detective – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)