Next time you're at the grocery store shopping for vegetables, just remember: these aren't your grandma's vegetables.

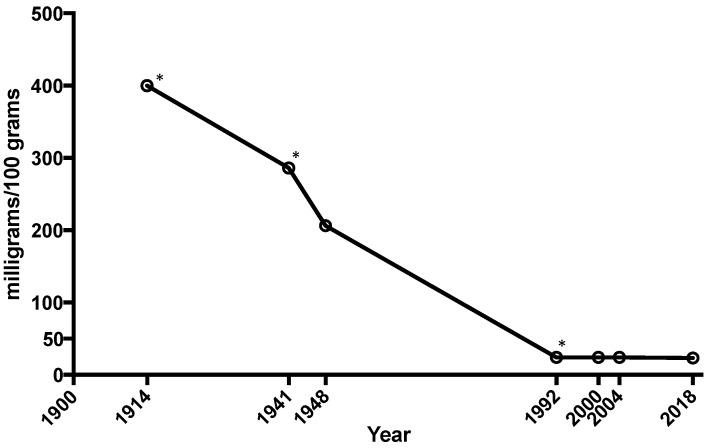

The average amount of calcium, magnesium, and iron in vegetables like spinach, lettuce, cabbage, and tomatoes has plummeted as much as 80–90% since 1914.[1] We have no choice but to supplement it back in.

Your grandma enjoyed fruits and vegetables with a significantly higher vitamin and mineral content than what's commonly available in stores today. The reason why is complicated, but it fundamentally comes down to soil quality.

Why we need more magnesium: Modern agriculture has failed us

Modern agricultural techniques don't take the soil cycle into full consideration and fail to remineralize topsoil after it's been used to grow a season's crops.[1-6]

As a result, the mineral content of the soil – and hence, of the crops grown in that soil – has steadily declined over the past century. Magnesium is in particularly short supply these days. According to some estimates, as much as 80 or 90% of soil magnesium has been lost to crop monoculturing,[1-6] which is the practice of growing just one type of crop at a time on a field, ultimately reducing biodiversity.

It would be great if we could remineralize the soil our food comes from, but since most of us are not in a position to grow our own crops or raise our own livestock (which is the best way to fertilize the soil), we must look for an alternative solution to this problem: magnesium supplementation.

Get ready for a master class in not just magnesium, but glycine as well. If there were only one ingredient we'd suggest to improve sleep, it'd be Revive MD's Magnesium Glycinate, third-party tested and all.

Should I supplement magnesium? Almost definitely.

Considering that in the United States, an estimated 50% of adults don't get enough magnesium from their diet,[7,8] the answer to the question "Should I take a magnesium supplement?" is very likely "Yes." According to the recommended daily allowance (RDA) set by the USDA, you are at least as likely as not to be deficient in magnesium to some degree.

So it's not surprising, considering how endemic magnesium deficiency really is, that magnesium supplementation was found in a 2017 meta-analysis to significantly improve the symptoms of anxiety commonly associated with magnesium deficiency.[9]

Revive MD Magnesium Glycinate: A bioavailable form of magnesium

With that in mind, let's take a look at Magnesium Glycinate from Revive MD, and explore why this form of magnesium is uniquely effective compared to other supplements.

The science is below, but first, let's take a break and look at PricePlow's coupon-based prices:

Revive MD Magnesium Glycinate – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming Ingredients video.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Revive MD Magnesium Glycinate Ingredients

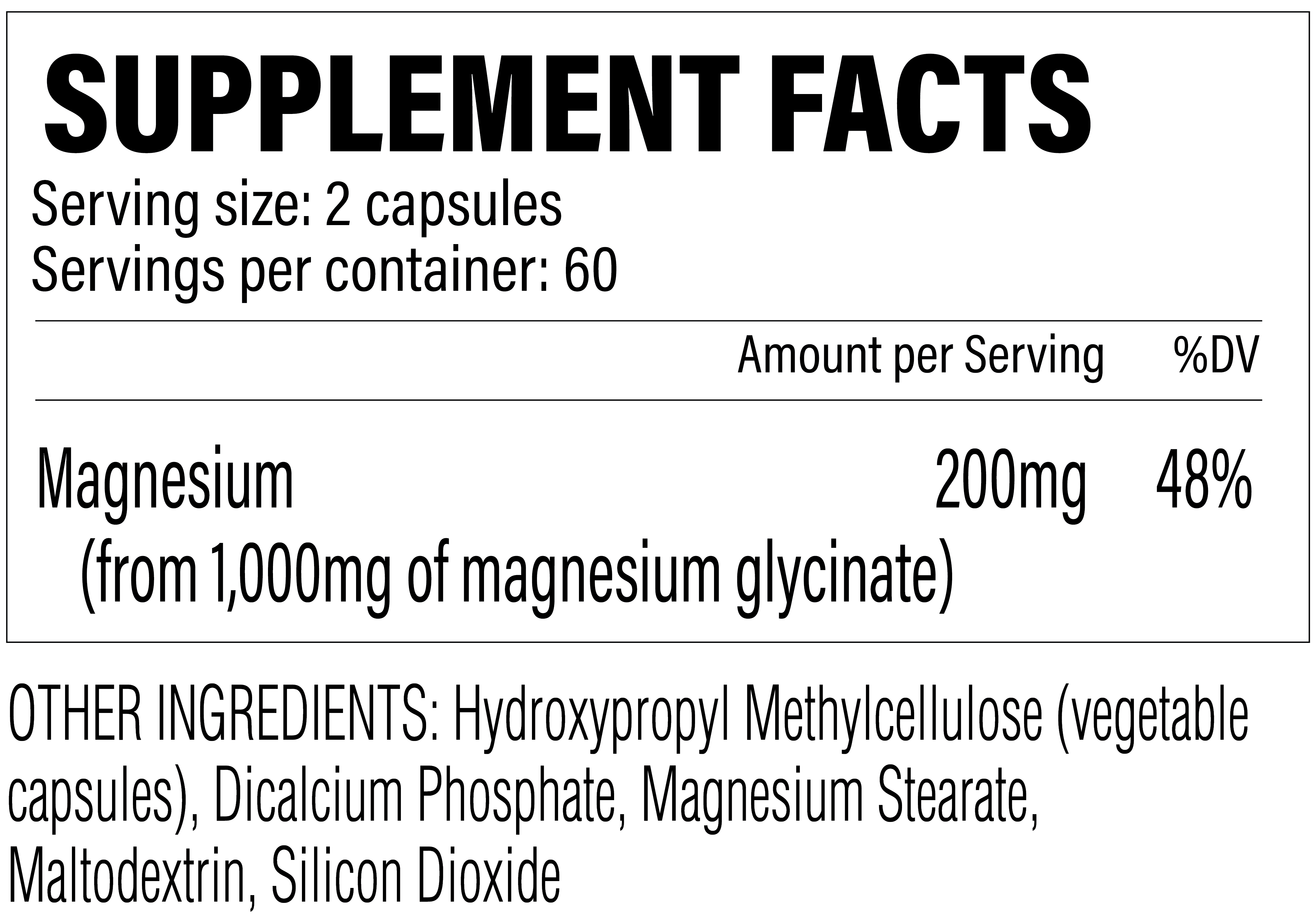

Each two-capsule serving provides 1000 milligrams of magnesium glycinate yielding 200 milligrams of elemental magnesium - but both components (magnesium and glycine) deserve attention, so they're covered individually below:

-

Magnesium (as Magnesium Glycinate) - 200mg

Revive MD Magnesium Glycinate Ingredients: 200 milligrams of magnesium, but also 800 milligrams of glycine!

Two capsules provide 1,000 milligrams of magnesium glycinate, which equates to 200 milligrams of elemental magnesium. This form is bound to glycine, meaning we get 800 milligrams of it -- a non-trivial amount. For this reason, we actually cover glycine's benefits below.

First, let's get into magnesium, the main (but not only) reason we're here:

Magnesium: combat stress, anxiety, and more

If you're deficient in magnesium, you can expect to have elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and fatigue.[10-12] This is largely because magnesium is crucial for regulating neurotransmitter function in the brain.[10] It's also a second-order effect of adequate magnesium stores being crucial for proper sleep, and the fact that insomnia, or compromised sleep quality, is an independent risk factor for psychological and emotional problems.[13]

In fact, according to one 2015 study, low magnesium intake was associated with a 22% increase in risk of depression among people under the age of 65.[14]

Improved sleep

Several peer-reviewed papers have shown that magnesium supplementation can significantly improve the duration and quality of human sleep.[15-18] The specific mechanism of action by which supplemental magnesium does this seems to be its cortisol-lowering effect, which helps normalize a person's sleeping patterns.[16]

Another study showed that magnesium intake was correlated inversely with a person's midpoint of sleep, meaning that people with a high intake of magnesium get to bed earlier than those with low intake.[19]

Other effects of magnesium

Magnesium is involved in a cofactor for over 600 different metabolic processes in the human body[20] – a huge number – so it's no surprise that if you're deficient in magnesium, you'll end up dealing with a ton of pretty awful downstream health effects.

Besides improving sleep and reducing anxiety, previous studies have found that magnesium supplementation can potentially:

- Reduce blood pressure[22-25]

- Lower HbA1c and blood sugar levels[22,26,27]

- Lower fasting insulin levels[22,26,28]

- Increase insulin sensitivity[22,26,27,29]

- Lower risk of type 2 diabetes[30-32]

- Increase bone density[33]

- Reduce PMS symptoms[34-37]

- Improve lactate clearance during and after exercise[38]

- Increase muscle mass and power[39]

- Reduce blood levels C-reactive protein[40] and blunt its effects[41]

- Lower levels of pro-inflammatory interleukin 6 (IL-6)[42]

- Protect against muscle damage during endurance exercise[43]

- Prevent and reduce migraine attacks[44,45]

- Acutely relieve an ongoing migraine attack[46]

These aren't fringe benefits. This is an essential mineral with system critical functions.

Why magnesium works

The "big picture" view on why magnesium works is that it's an inhibitory compound. Whereas magnesium's excitatory antagonist calcium stimulates nerve action, thus "exciting" them,[47] magnesium actually inhibits nerve action, thus calming down them.[48] So calcium is required for muscles to contract, whereas magnesium ends the contraction and causes muscles to relax.

Similarly, Revive MD's Zinc is out, and it brings 50mg elemental zinc from OptiZinc (zinc monomethionine). is out, and it brings 50mg elemental zinc from OptiZinc (zinc monomethionine).

In fact, magnesium is consumed at an elevated rate during exercise[49] so athletes, and other highly active individuals, have an added reason to consider magnesium supplementation.

On the dosage

The recommended daily magnesium dose depends on age and gender— it'll be somewhere between 240 and 420 milligrams.[19] Two capsules here is 48% of the upper end of that, but we can also assume that you'll get more from your diet throughout the day.

Too much magnesium can result in unwanted trips to the toilet, so a 200 milligram dose is a smart play -- also consider what's in the rest of your supplement stack. If not taking any other magnesium-containing supplements, you can test three or even four capsules... you'll know when you've had too much by way of bowel movements, and should logically reduce the dose after such an episode.

-

Glycine (as magnesium glycinate) – 800 mg

The second portion of the magnesium glycinate molecule is glycine, a conditionally essential amino acid with documented anti-stress and pro-metabolic effects. Normally with a supplement like this, we're here for the magnesium, but beyond improving magnesium's absorption, this dose of glycine may impart its own benefits, so we expand in detail below.

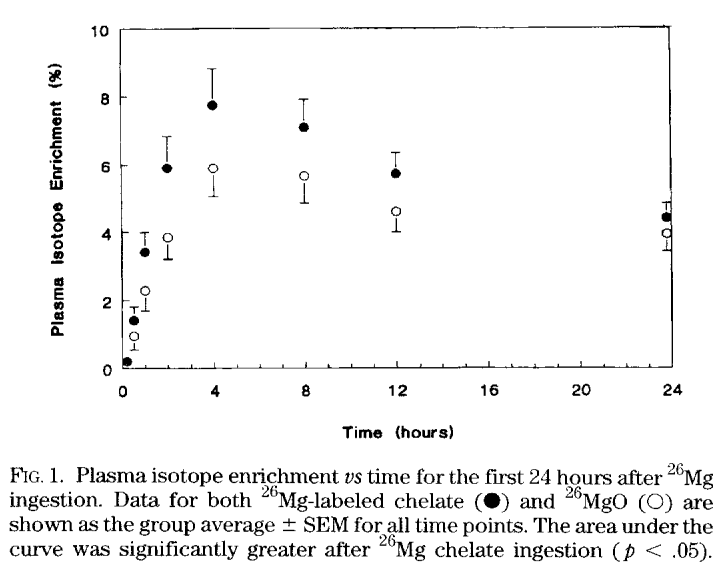

The main reason for binding magnesium to glycine is that glycine is a great delivery vehicle for magnesium. Though pure minerals aren't absorbed much by the small intestine, amino acids like glycine are. Thus, you can improve the bioavailability of magnesium by pairing it with a high-absorption amino acid like glycine, and this is what many supplement manufacturers have started doing with their mineral supplements.

Research studies that have set out to answer this specific question consistently find that glycinated minerals have a higher bioavailability than pure or "free" minerals. In one study, magnesium glycinate specifically was found to have much better bioavailability than magnesium oxide,[21] a form that we basically never recommend.

So with a glycinated supplement, you're getting way more bang for your buck, and a much bigger effect size than you would with the typical non-glycinated mineral supplement.

But glycine isn't just a delivery vehicle for minerals.

One of the best reasons to pair glycine with magnesium is that the two compounds have similar effects. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of pure glycine supplements on the market today for the reasons given below.

The health benefits of glycine

To start by giving you a rough idea of glycine's importance for human health, 12% of the body's total amino acid stores consist of glycine.[50] Glycine is used in protein synthesis, including the proteins collagen and elastin, which are used to make the body's various connective tissues.[50] This is why the meats rich in glycine tend to be firmer cuts, i.e. various organ meats – because the high glycine content comes from their collagen content.

Glycine and sleep

Of glycine's many effects on human health, the most relevant to our discussion of Revive MD's magnesium glycinate supplement is the documented positive impact that glycine has on sleep quality.[51-59]

In one 2006 study, subjects were given glycine to take before bedtime for four days. At the end of the study period, the researchers gave subjects a questionnaire designed to quantify subjective feelings like "fatigue," or "clear-headedness" or "liveliness and peppiness."[60]

Compared to the control group, those who took glycine reported better quality sleep, and they had significantly more energy upon waking.[60]

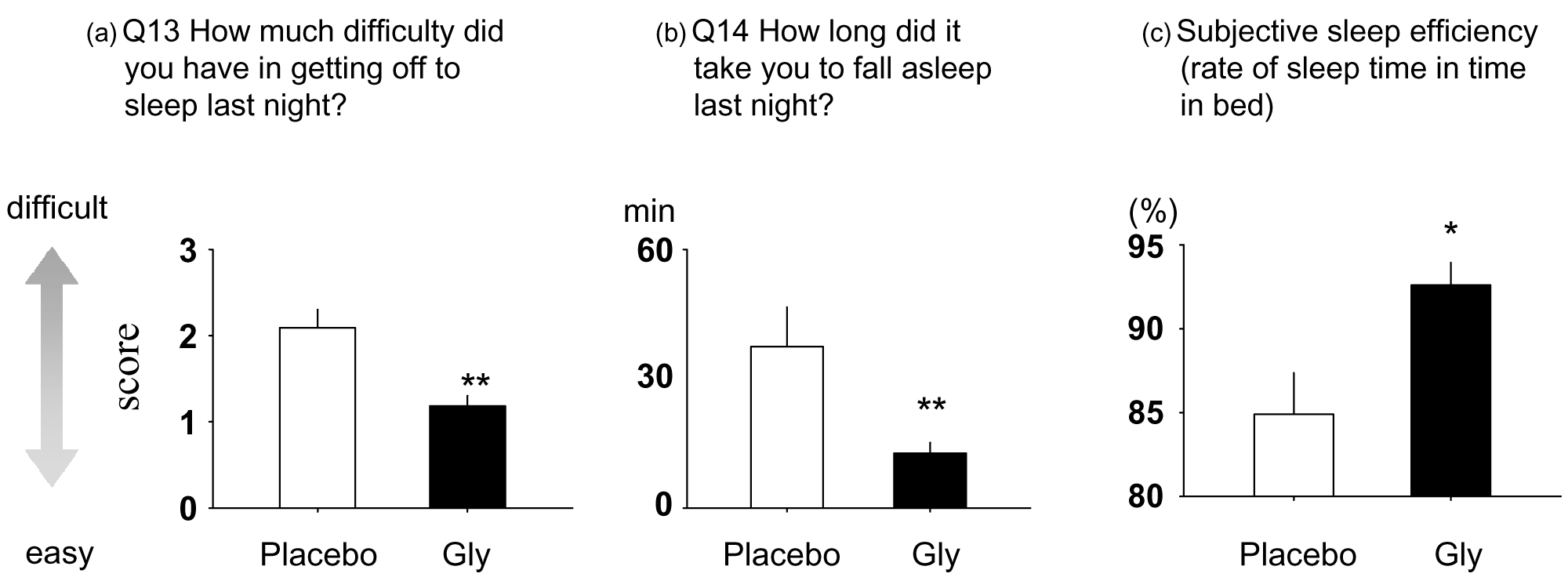

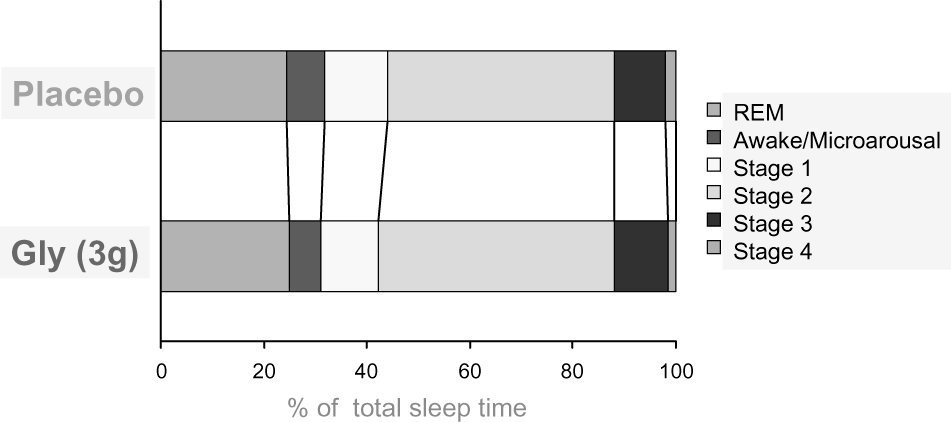

Another study, this one published in 2007, used a randomized, single-blind crossover design where 11 volunteers received either 3 grams of glycine or a placebo before bed, with researchers monitoring their sleep quality overnight.[59]

- The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the St. Mary's Hospital (SMH) questionnaire inventories were used to measure sleep quality. Moreover, subjects were monitored with polysomnography, which tracked brain activity by measuring electrical impulses, movement, and vital signs.[59]

- The Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS), visual analog scale (VAS) and a memory test were used to quantify daytime cognitive function.[59]

The researchers in this study used the following metrics to measure the quality of the subjects' sleep:

The results were that the subjects who took glycine had better satisfaction with their sleep compared to the placebo group. They fell asleep faster and had less difficulty falling asleep,[59] and the polysomnography measurements reported by the researchers were consistent with these subjective responses.

According to the polysomnography data taken by the researchers, the glycine group had a longer duration of deep sleep, fewer nighttime awakenings, and significantly shorter time to sleep onset than the placebo group.[59]

Moreover, according to their SSS and VAS scores, the subjects who took glycine were significantly more awake and showed better cognitive performance than the control group.[59] The glycine group did better in a memory test that was given in the middle of the day.[59]

In a follow-up 2012 study published in Frontiers in Neurology, researchers repeated the study design of the 2007 study and found that the cognitive improvements from glycine supplementation lasted for several days after the end of the experiment.[61]

Considering the close association between sleep, anxiety, and stress, it's safe to say that glycine can provide additional help with most goals that you're trying to achieve with magnesium supplementation.

Consider adding more glycine if you're looking for even better sleep

It's worth mentioning that if you're interested in glycine's sleep research, you're not going to get the full clinical benefits at 800 milligrams - 3000 milligrams is where much of the research lies.[59] If you wish to go all in on glycine, adding another couple of grams before bedtime is a good idea.

Glycine's mechanisms of action

Glycine has a dual nature in the human central nervous system (CNS): it can both inhibit transmission between neurons in the context of its own signaling system, and facilitate transmission between neurons in the glutaminergic system.

In glycinergic transmission, glycine inhibits transmission between neurons in the brainstem and the spinal cord. This anti-excitatory effect influences several areas of the brain, including, but not limited to, the thalamus, cerebellum, and hippocampus.[62-64]

In glutaminergic transmission, glycine stimulates the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors,[65,66] which play a central role in learning and memory,[67] as well as overall brain health.[68] N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors are so important for healthy cognitive aging that in rats, NMDA stimulation has been shown to partially reverse the impairment of long-term potentiation (LTP) associated with Alzheimer's disease.[69] In plain English, LTP can be understood as memory consolidation.[70] Anything that increases LTP is going to improve memory across the board, and in the research literature, it has been found that LTP function predicts human performance on memory tests.[71]

In a 2019 study published by the journal Sleep Research Society, researchers found that NMDA receptors are critical for proper sleep regulation and for the memory consolidation that occurs during both rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.[72]

Another study, this one published in 2015 by the journal Neuropsychopharmacology, found that mice given glycine showed much less wakefulness[73] and sleep onset that was 20 minutes faster than the control group. Additionally, glycine increased total NREM sleep.[73] The glycine group also showed an increased loss of peripheral heat,[73] an effect that signifies improved sleep latency and is mediated by NMDA receptors.[73] Glycine increases peripheral heat loss by activating NMDA receptors in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and medial preoptic area (MPO), regions of the hypothalamus that control body temperature.[73]

Glycine contributes to muscle atonia

Most of us are probably already aware that when we sleep, our muscles enter a state of intense relaxation that is key to achieving restfulness. This is called muscle atonia.[74]

According to a 1989 study from UCLA, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, glycine turns helps facilitate muscle atonia by controlling mediation of active sleep-specific inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (AS-IPSPs),[75] which creates the motor neuron inhibition observed during REM sleep.

Other benefits

Although glycine helps promote restful sleep (a big bonus for overall health), it has, like magnesium, many other effects as well. Similarly to magnesium, glycine can potentially:

Further manage your stress with the help of Revive MD Calm.

- Improve symptoms in patients with neurological disorders: In one 2004 study published by Biological Psychiatry, glycine administration was associated with a 23% reduction in symptoms for patients with diagnosed schizophrenia.[76] A 2009 case study published in Neural Plasticity found that a patient with clinical obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and body dysmorphia improved substantially while taking supplemental glycine on a daily basis.[77] The authors of both studies speculate that glycine-driven NMDA receptor modulation may be the mechanism responsible for its psychiatric effects.

- Improve insulin sensitivity: Insulin resistance is associated with low levels of glycine, implying that glycine supplementation might help achieve healthy blood glucose levels in people with the metabolic syndrome.[78]

- Prevent muscle catabolism: Under circumstances such as severe calorie restriction or certain diseases, glycine has been found to partially spare muscle tissue from being wasted.[79,80]

- Help prevent heart disease: Glycine has been observed to decrease platelet accumulation in vitro,[81] and a 2016 meta-analysis from the Journal of the American Heart Association determined that there is an inverse relationship between blood glycine levels and cardiovascular disease.[82]

The point is clear: magnesium glycinate isn't just about the magnesium.

Dosage and directions

At the end of the magnesium section, we cover our dosing suggestions - start with two capsules, and it's best taken before bed. If you know your diet is very low in magnesium (e.g. you don't eat many nuts, legumes, or dairy), you may want to try three or even four capsules. Let your bowel movements guide your dose back down if you go too high.

Takeaway: Magnesium glycinate is a slam dunk ingredient

It's not often that such simple supplement formulas have such an impressively deep and wide body of research backing their efficacy. Magnesium and glycine are two heavy-hitters that pretty much anyone should at least consider supplementing.

The only question is what dose is best for you and your diet, and if you want to consider adding even more glycine before bed.

All in all, though, if you were going to give us one ingredient to improve someone's sleep, it wouldn't be melatonin -- it'd be magnesium glycinate right here. And Revive MD, with its third-party lab tests, would be the brand to suggest.

Revive MD Magnesium Glycinate – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)