BodyTech Elite, the advanced supplement series born out of The Vitamin Shoppe's BodyTech brand, has been making some moves so far in 2024.

Those who are looking to make it a big year will be excited to see the new BodyTech Elite Altered Savage pre-workout supplement, which takes the energy, focus, and pumps seen in their Altered Strength pre-workout to the next level.

Getting after it this month? Then look beyond just protein powder and boost growth and recovery with BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB, powered by myHMB!

But after you're done training like an "Altered Savage", you're going to need some serious recovery. After all, if you're not making yourself sore, you're probably not going hard enough. But if you are hitting it hard enough to induce soreness, then there are some added tools to accelerate recovery and get you back to growth as soon as possible.

For this, most of us know of BodyTech's famous Whey Tech Pro 24 whey protein powder blend, but now there's even more to offer:

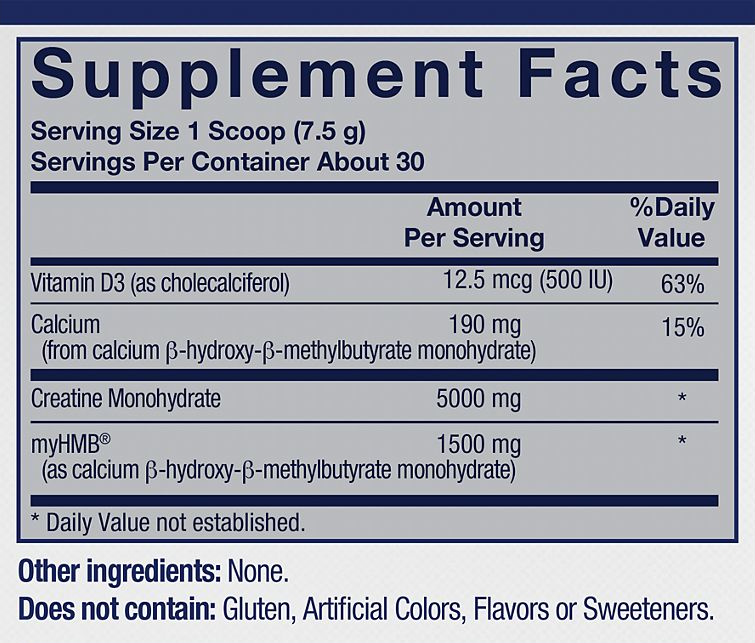

BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB: 5g Creatine Monohydrate, 1.5g myHMB (Calcium HMB)

Protein is obviously a piece of the recovery puzzle -- and beyond sleep, it's likely the most important one. But right after that comes creatine monohydrate, which supports a myriad of functions in the body by supporting the body's production of ATP, the high-energy molecule all cells rely on.

But a big part of the protein puzzle that's often forgotten comes from one of its primary amino acids' metabolites. We're talking about the leucine metabolite, HMB. Functioning primarily as a signaling molecule, HMB supports multiple "anabolic switches" to help prevent muscle loss, and, if you're training hard enough, increase strength and muscle growth.

Yet, as we'll see in the research cited below, only 5% of leucine gets converted to HMB (in best case scenarios), and that means some gains may be left on the table.

BodyTech aims to correct that issue, by providing a 1.5 gram dose of calcium HMB -- sold as myHMB by TSI Group -- alongside 5 grams of creatine monohydrate, in their new unflavored, unsweetened BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB.

In addition to covering the science of each of these below, we also look at some research where combining creatine and HMB outperformed each one individually! It's all below, but first, let's look at The Vitamin Shoppe's product pricing and availability:

BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

Research on Creatine + HMB Used Together

Before we get into our separate ingredient research, let's touch on the studies trialing creatine and HMB together. There have been two research trials producing three different publications:

-

2001: Creatine and HMB additively increase lean body mass and muscle strength

In this study, which lasted 3 weeks, 40 healthy young men were split into four separate groups:[1]

- CaHMB: Calcium HMB (3 grams per day in 3 equal daily doses of 1 gram each)

- CR: Creatine monohydrate loading protocol (20 grams per day for 7 days, then 10 grams per day for 14 more days).

- CR/HMB: The combination of HMB and creatine monohydrate, as dosed above

- Placebo (glucose and rice flour)

All participants were a part of a 3-week resistance training program featuring full-body, progressive training 3 days per week.

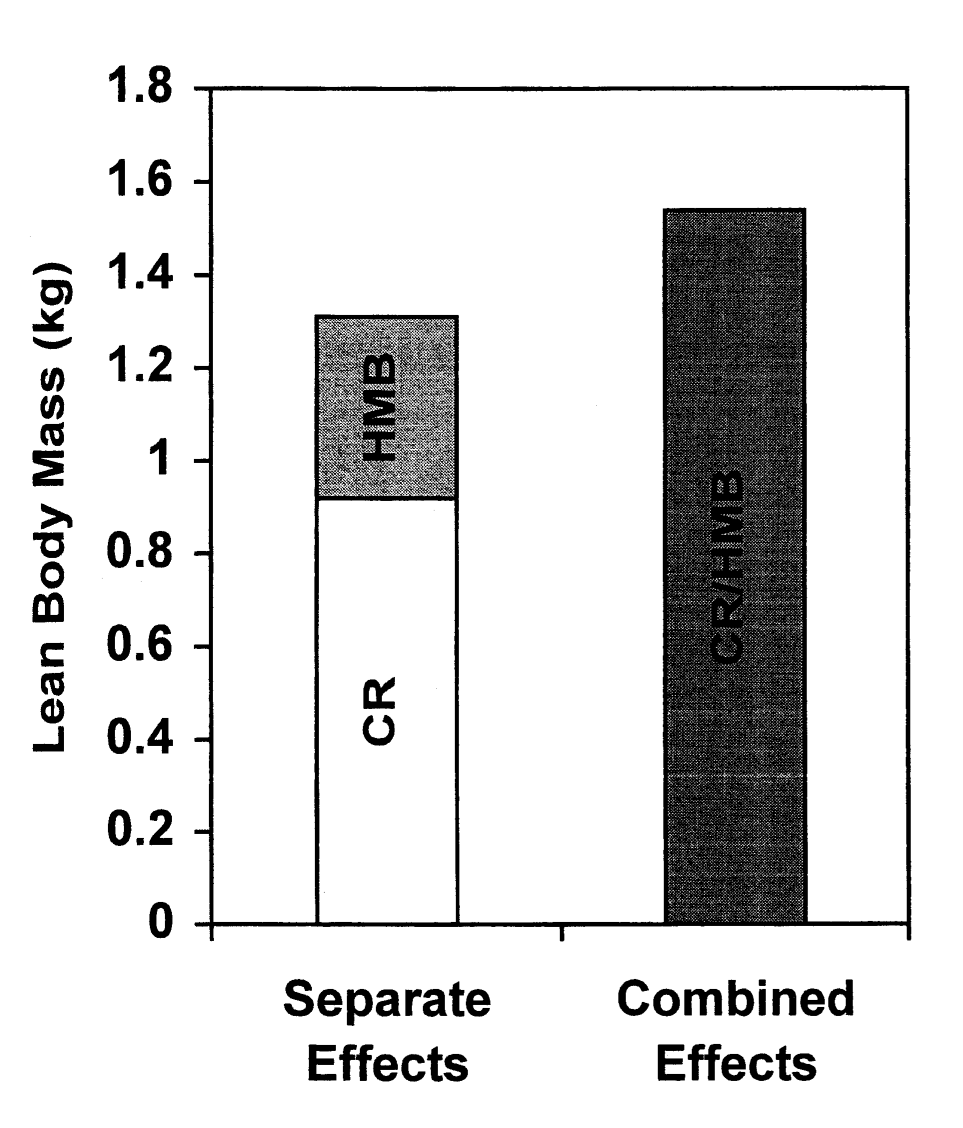

Results: Synergistic lean mass gains

Both creatine monohydrate and HMB improved lean body mass and strength gains, which is expected.

In terms of lean body mass, Creatine + HMB beat the sum of creatine and HMB separately[1] -- that's true synergy!

However, the data showed that the lean mass gains were synergistic in the CR/HMB group, where their gains were greater than each one taken alone:[1]

- CaHMB: 2.73 pounds

- CR: 3.9 pounds

- CR/HMB: 5.27 pounds

- Placebo: 1.87 pounds

Next, let's look at strength:

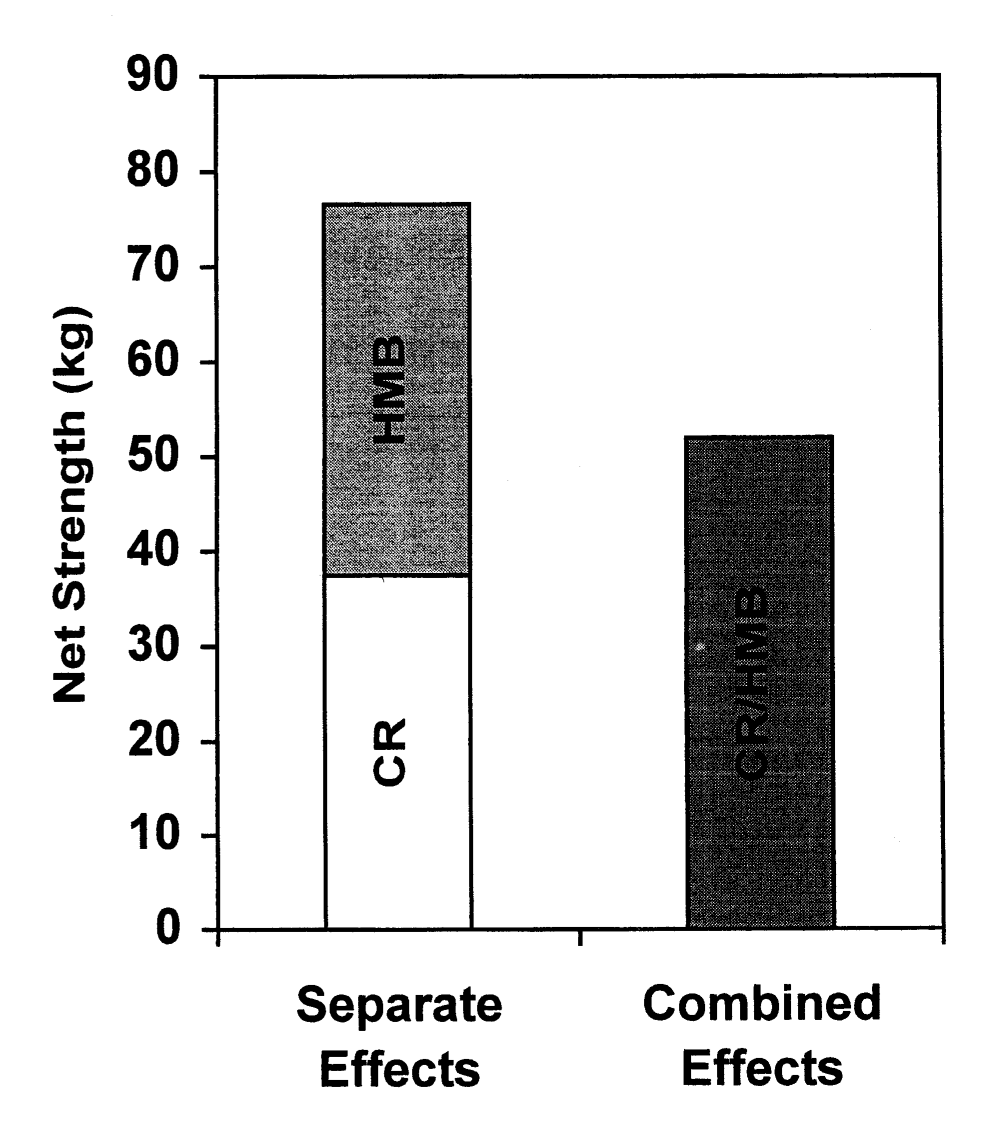

Results: Additive strength gains

Spread across bench press, power clean, behind-the-neck press, biceps curl, squat, triceps extension, strength gains were similar:[1]

- CaHMB: 129.9 pounds

- CR: 126.3 pounds

- CR/HMB: 157.9 pounds

- Placebo: 43.5 pounds

This suggests that lean mass and strength gains were additive, although there may have been some overlapping effects or a "ceiling effect". It's quite tough to put on this much lean mass and strength so quickly without a serious training program.

For strength, Creatine + HMB performed better than creatine and HMB separately,[1] but not more than each separately like with lean body mass. Still extremely impressive!

Given that the placebo group gained almost 2 pounds of lean mass in three weeks indicates that they had a pretty solid training system, but the combination of creatine and HMB certainly sored ahead.

Note the double-dosing

Now, it's important to note the doses used here, which are as the studies below. In order to achieve this, you would need to double the dosage of BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB, and add 10 grams of extra creatine for the first week as a "loading" period.

While we have gotten away from loading since the study was performed, there is so much research showing that it's successful. And given that creatine's not nearly as expensive, it's not a bad idea to give it a shot if you're new to creatine.

The next study is more recent, and ran for over 3 times longer:

-

2020: Ten Weeks of Creatine Monohydrate Plus HMB Supplementation on Athletic Performance in Elite Male Endurance Athletes

Published in 2020, this experiment received two publications: one focusing on performance effects,[2] and the other focusing on muscle damage and hormones.[3]

This trial lasted 10 weeks long, employing 28 elite male rowers randomized into four groups:[2,3]

- CaHMB: 3 grams per day

- Creatine: 0.04g/kg per day (for a 185 pound male, this is ~3.36 grams per day)

- CR+HMB: The combination of the above two

- Placebo

The supplements were mixed into a post-workout recovery shake (1 g/kg of carbs + 0.3 g/kg protein), or were taken before bedtime on non-training days.[2,3]

The workouts were 1.5 hours long, and included rowing practice as well as strength training and recovery protocols during rowing season, performed 6 days per week - serious training.

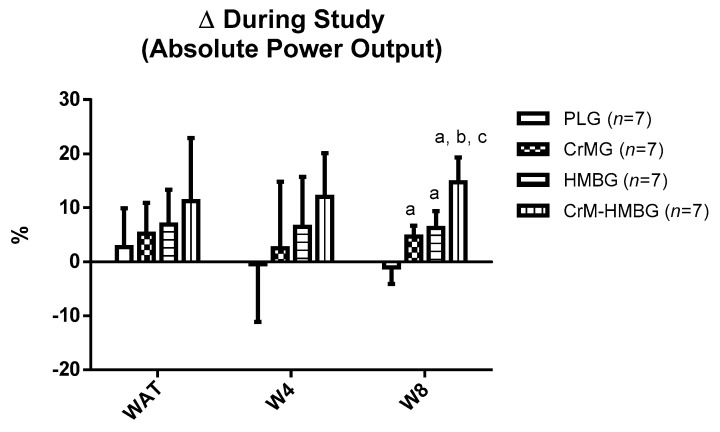

Results: Lean Mass and Power Gains

Each creatine and HMB group reduced BMI a significant amount, but the placebo group did not achieve statistical significance in this metric.[2]

Creatine + HMB significantly increases power output more than each separately - especially at the 8 mmol/L (W8) blood lactate level.[2]

Impressively, the power increases at anaerobic threshold were significant in the HMB and CR+HMB groups, although there were no significant differences between those groups.

In terms of power at 8mmol lactate -- an important type of metric for rowers -- all groups had increases, but the CR+HMB group showed synergistic gains! Here, the CR+HMB group gained 14.9 while the CR and CaHMB groups gained 4.7 and 6.4.[2]

Similar excellent power gains were on the anaerobic threshold (WAT) measurements, where only CaHMB and CR+HMB were statistically significant.

This data demonstrates a synergistic benefit of creatine and HMB on anaerobic work performance.

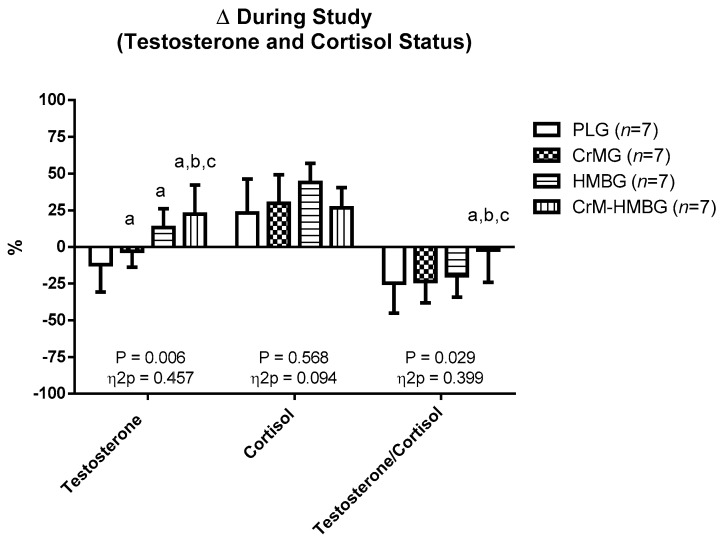

Hormones: Creatine + HMB Increases Testosterone 22%!

It's well-known that this level of training can sap testosterone levels and elevate cortisol levels. While the placebo group unsurprisingly saw a non-significant drop in testosterone, the CR+HMB group had a significant increase in testosterone - 22%![3]

The Creatine + HMB group increased testosterone so significantly that it basically "corrected" for the increase in cortisol,[3] which is tough to keep down with this level of training.

Creatine on its own had a slight, non-significant reduction in testosterone, while CaHMB had a decent (yet non-statistically significant) increase in testosterone. Yet the combination of the two did achieve significance, despite all groups having elevated cortisol.[3]

Additionally, CR+HMB did not experience a drop in testosterone:cortisol ratio -- the testosterone increase was powerful enough to overcome the increase in cortisol. Overall, this indicates that the combination of creatine monohydrate and calcium HMB are quite synergistic in protecting the body from overtraining.

The lesson: creatine and HMB for those extreme training runs

Ultimately, the moral of the story remains the same from our previous articles on HMB: If you're getting after it in a big way and feel that you're going to be running into soreness, overtraining, or catabolism -- HMB needs to move higher up your priority list.

Now let's talk about both of these two ingredients separately, to understand the mechanism a bit.

BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB Ingredients

-

Creatine Monohydrate - 5000 mg

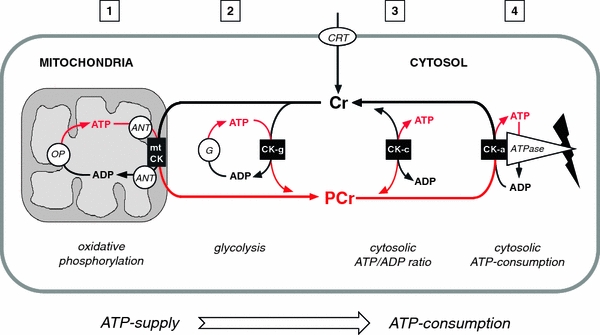

Creatine is a molecule produced in the body that's made up of three amino acids -- methionine, arginine, and glycine. It stores phosphate groups used to help produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP),[4] the body's main energy carrier and the usable energy source for nearly all cells. Amongst ATP's numerous roles, it's heavily used for muscle contractions[5] and intense mental activity.

Thanks to creatine's supportive role in ATP generation, and ATP's role in muscle contractions, creatine supports immediate energy production during exercise - especially when muscle glycogen becomes depleted.[6] Supplemental creatine has been shown to boost overall strength and performance in numerous training and sporting scenarios,[7] much of which will be detailed below.

How much creatine do I need?

Your creatine requirements are different for each person but depend on three major factors:

- Your size and muscle mass

- Your diet (specifically meat consumption)

- Your physical activity

The goal is to achieve a saturation of creatine in the muscle tissue so creatine can be deployed as needed during training. This requires a bit of work to determine each person's individual needs, although there are some general guidelines that suit most athletes:

Creatine storage in the body

A study published in 2011 does a fantastic job showing creatine's role in the production of ATP in the mitochondria.[8]

The male body has capacity to store up to 160 grams of creatine.[4] However, the total amount of creatine has been found to be 120 grams in the average man,[4] 95% of which is stored in skeletal muscle tissue. Small amounts are also stored in the brain and reproductive organs.[9]

The excretion of creatine

Humans excrete about 1.6-1.7% of their creatine stores per day.[10,11] This means that on average, males excrete about two grams of creatine per day,[12] although the actual number will depend on size and muscle mass. Women lose a bit less - roughly 80% of men.[12]

Dietary sources of creatine

Much of your creatine needs can be met by your diet, but it will ultimately depend on how much meat you consume. For instance, red meat is the best food-based source of the molecule, with about 2-2.5 grams of creatine per pound of uncooked beef.[13] Chicken comes in a bit lower, with roughly 1.5 grams of creatine per pound.[14]

The final intake strategy: achieve and maintain saturation

All told, this helps paint a picture as to why we want to achieve saturation of creatine in the muscle tissue and then stay at saturation. Older protocols (and several successful studies) in the late 1990s and early 2000s involved loading with 20 grams of creatine per day for 5 days, and then taking 5 grams per day thereon. This still works and will likely help achieve saturation more quickly but is more costly and potentially wasteful, especially in today's inventory landscape.

Those who are in less of a hurry will generally take 2-5 grams of creatine per day, every day, depending on gender, size, and exercise intensity. Without knowing any other lifestyle or diet details, our simple dosing suggestion is as follows: For women, 2-3 grams per day is a reasonable amount, while men can aim for 3-5 grams per day.

The athletic benefits of creatine

With creatine's role as a phosphate donor that facilitates ATP production, and ATP's energetic role throughout the entire body, creatine can have a wide array of health benefits. For the sake of this article, however, we're focusing on athletic benefits.

There have been hundreds of peer-reviewed studies evaluating the efficacy of creatine supplementation in improving exercise performance, and we can't possibly cover them all. A 2003 review analyzed roughly 300 studies evaluated creatine's effect on performance and found creatine supplementation generally leads to 5-15% improvement in the variable of interest.[15]

The rule of 5-15%

Published research has found short-term creatine monohydrate supplementation typically leads to:[15]

- 5-15% improvement in maximal power/strength

- 5-15% increase work during maximal effort muscular contraction sets

- 5-15% increase in work performed during repeat sprint bouts

- 1-5% improvement in single-effort sprint performance

There have been far more creatine studies published since then, and the results/ benefits are seen across numerous sports and events.

Short-term creatine use

Creatine supplements have supported short-term adaptations such as total work performed on the bench press and jump squat, increased cycling power, and improved sport performance in sprinting, swimming, and soccer.[15,17-23] Studies have also supported creatine's use in both males and females.[18,24-26]

Long-term creatine use

Further research has shown long-term creatine intake is beneficial to both muscle performance and lean body mass.[21-24,27-29]

Most researchers agree these effects are thanks to an improved ability to perform high levels of intense training thanks to better ATP synthesis. With so many studies conducted on creatine in athletes, the research community is led to conclude it is an incredibly effective and reliable supplement,[16,30] and one we believe that should be in nearly every athlete's regimen.

Creatine safety

When creatine supplements first gained popularity in the 1990s, they were mired in controversy and misinformation -- much of which still exists to this day. Thankfully, common sense dietary intuition (creatine is naturally found in food) coupled with safety research has prevailed.[30-34]

The most common reported "side effect" of creatine use is weight gain,[33] which is often the intended effect in many athletes. Anecdotal case studies sometimes report dehydration and cramping, but these are not supported in peer-reviewed studies on healthy individuals.[30]

An official position stand published in 2007 by the International Society of Sports Nutrition on creatine supplementation and exercise lists nine major points approved by the Society's Research Committee, one of which states "There is no scientific evidence that the short- or long-term use of creatine monohydrate has any detrimental effects on otherwise healthy individuals."[30]

In the years since that position stand was published, there have been no new research studies that indicate the contrary. However, a newer 2022 review cites 255 other articles maintains that creatine monohydrate has "Strong Evidence to Support Bioavailability, Efficacy, and Safety".[16]

Creatine Monohydrate: The main forms of creatine

There are hundreds of commercially-sold creatine supplements on the market, with over a dozen types of creatine compounds available for brands to use. The most well-established form of creatine is easily creatine monohydrate, though.[35]

It's the subject of the vast majority of research studies cited above, and consists of each creatine molecule bound to a water molecule, making it 88% creatine by weight.[35]

Our take is that the form of creatine matters less than compliance and dose, but when in doubt, go for the tried-and-true creatine monohydrate.

-

myHMB (as Calcium β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate monohydrate) - 1500 mg

Distributed by the TSI Group, myHMB is a patented form of HMB, which is a metabolite of the branched-chain amino acid L-leucine.

Read the full story in PricePlow's main HMB Supplements article.

HMB is actually primarily a signaling molecule, shown to activate many of the same "metabolic switches" as leucine, which includes both mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin)[36] and IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1),[37] both of which are well-known to be anabolic.

Many athletes know of leucine's anti-catabolic effects (it prevents muscle breakdown),[38-40] but that requires extremely large doses -- well into the double-digits of grams.

What we now know is that leucine's metabolite HMB is largely responsible for those effects, yet only ~5% of leucine is converted to HMB in the best of situations![41] This is where HMB supplementation comes in, to get the effects without needing to eat massive amounts of protein and leucine.

Human research on HMB

HMB's been around for a while, so we have a great deal of research supporting its use. Here's what we've seen in human subjects taking 1.5-3 grams daily, as collected in the International Society for Sports Nutrition (ISSN)'s position stand:[42]

- Improved muscle and strength gains paired with resistance training[43-45]

- Greater athletic endurance and overall work capacity[46-49]

- Reduced post-workout muscle damage[50,51] and recovery speed[52]

- Promote leaner body composition[53]

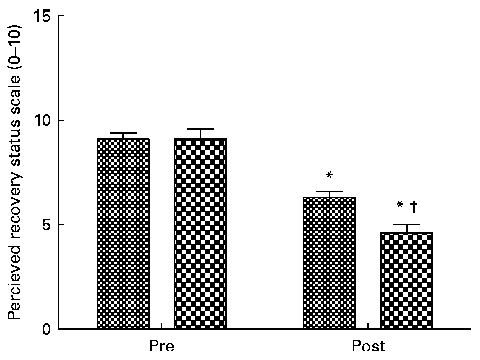

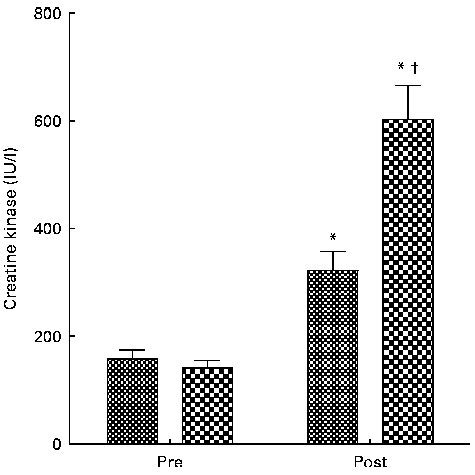

Resistance-trained subjects who took HMB before a high-volume weightlifting session rated their recovery significantly higher 48 hours afterwards, compared to the placebo group.[51]

For instance, one of these studies, published in 2014, was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled test on resistance-trained males who went through a rigorous three-phase periodized training program with an overreaching cycle.[45] It used 3 grams of HMB per day, which would require two daily servings of BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB.

The researchers tracked muscle mass, strength (using 1 rep max tests), and hormonal blood markers.

They found that the placebo group gained ~6% total strength, which is a testament to the training program. However, the HMB group gained 17% strength -- almost 3x the effect -- and they also lost significantly more fat![45]

Preventing muscle-loss and muscle-wasting

Before there were studies on building muscle, it's also important to note how HMB supports the reduced loss of muscle in demographics where this is of critical importance. This was demonstrated in a 10-day study with older adults on bed rest, where 3 daily grams of calcium HMB significantly reduced the loss of lean body mass.[54]

Resistance-trained subjects who took HMB before a high-volume weightlifting session had significantly lower blood levels of creatine kinase (CK), a marker of muscle damage, following the session. The bars with larger checkering represent the placebo group; the bars with finer checkering represent the HMB group.[51]

Over time, more data has come to support HMB's use in injury and sickness -- a meta-analysis published in 2015 concluded that HMB supports significant reductions of muscle loss during aging, especially when it comes to injury, sickness, or those who are bedridden.[55]

Other studies in elderly subjects found significantly increased strength over placebo when using HMB combined with resistance training.[56,57]

We get into the mechanisms in our main article titled HMB (β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate): Performance-Driven Muscle Supplement. However, it's important to note a few things regarding the direction of HMB research:

Some caveats and research discretion:

There are two caveats when it comes to HMB and the research cited above. It's important to honestly discuss them:

-

In terms of building muscle, HMB works best in aggressive training programs

HMB is pretty well-documented to prevent muscle-wasting, but there are some cases where it did not generate muscle gains on its own. This is discussed in the ISSN's position stand, which makes the following statement:[42]

"...research [on HMB effectiveness] indicates that in trained populations it is critical that the exercise stimulus is of adequate intensity and volume to cause skeletal muscle damage. If these conditions are lacking, HMB is not likely to be efficacious."[42]

At this point, we're pretty comfortable stating that HMB is going to work best for those who repeatedly train to true soreness. You can still use it if you're just doing a standard 3 sets of 10 without much push to failure or periodized training, but that's not where this ingredient accels.

-

There is some fraudulent research on PubMed that still hasn't been retracted

Brought to our attention in PricePlow Podcast Episode #093 with HMB researcher Shawn Baier, there's sadly some research published on "HMB" that was actually using a fraudulent supplement that didn't have any HMB in it at all!

Shawn Baier joins PricePlow Podcast Episode #093 to talk HMB.

This happened in 2010, where three researchers published a study claiming that an over-the-counter supplement with "3 grams of HMB plus α-ketoisocaproic acid" did not work compared to placebo.[58] Those results made no sense, however, so another team of HMB researchers bought the product used in that study, had it tested, and realized it contained no HMB![59]

After writing a letter to the journal (the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research),[59] the original researchers admitted to their faulty study and that the product indeed contained no HMB,[60] but never retracted the original study! While their admission of guilt is admirable, this study still lies on PubMed without a red flag retraction notice, and this is a shame because it has swayed some individuals from using HMB... even though it wasn't even using the ingredient!

We hope that at some point, that study will be retracted by the authors or the journal.

The above story is the reason why TSI Group's myHMB is the only HMB to trust. When it comes to training this hard, there's no point in squandering potential gains.

You can learn more in our podcast with HMB researcher Shawn Baier and our article titled HMB (β-hydroxy β-methylbutyrate): Performance-Driven Muscle Supplement.

We're not done yet though -- there's even more research involving Vitamin D -- so let's get to that next:

-

Vitamin D3 (as cholecalciferol) - 12.5mcg (500IU) (63% DV)

While many supplement Vitamin D3 over the winter as sunlight gets more dim, that's not why it's in BodyTech Elite's Creatine + HMB!

Early on, HMB researchers noticed that some older individuals did not respond as well to HMB as others.[61] Upon investigation, they noticed that many had poor metabolic status, and one biomarker of note is that they had low serum Vitamin D3 levels![62] Those who had low vitamin D levels did not respond, while those were were sufficient did far better![62]

This is explained around the 1:05:00 mark in our podcast with HMB researcher Shawn Baier.

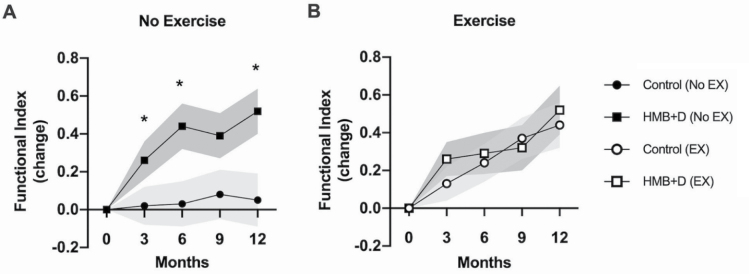

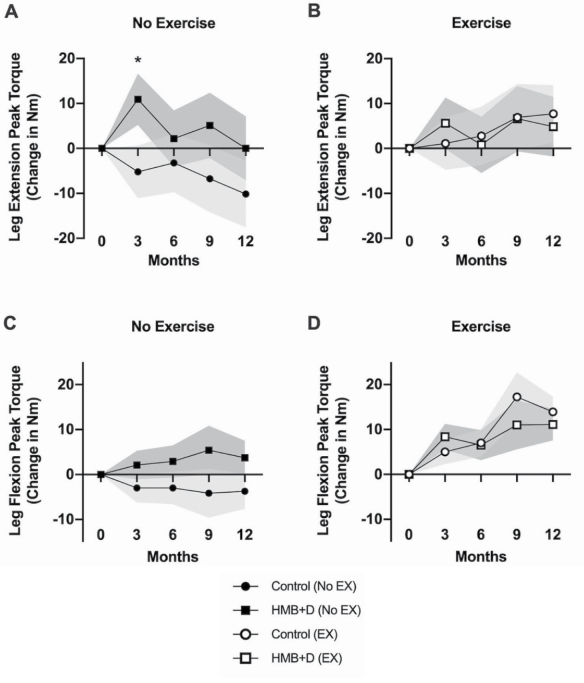

To verify if supplementing additional vitamin D3 would help in these situations, researchers conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study in elderly individuals with low vitamin D status that lasted 12 months.[63]

Elderly adults who supplemented with a combination of HMB and vitamin D made significant gains on a muscle function index compared to the control group. The effect size was approximately equivalent to that achieved by a resistance training program.[63]

They randomized individuals into created four groups:

- HMB + Vitamin D + Exercise (resistance training)

- HMB + Vitamin D

- Placebo + Exercise (resistance training)

- Placebo (no resistance training)

Compared to the non-exercising placebo group, the non-exercising HMB + vitamin D group gained significant leg flexion torque. Although HMB+vitamin D with no exercise did not significantly increase leg extension torque through month 12 of the study, the non-exercise control group actually lost leg extension torque, while HMB + vitamin D preserved it.[63]

What they found is that the adults who supplemented the combination of HMB + Vitamin D had significant gains in muscle function compared to the control group.

Interestingly, the HMB + Vitamin D group that had no exercise also gained strength and muscle function - significantly more than the non-exercising placebo group![63]

In terms of peak torque on leg flexion and leg extensions, HMB + Vitamin D + Exercise had the greatest benefits. Sad but not unexpected, the non-exercise placebo group lost strength.

While this is a study in older individuals, it shows that there could be some solid synergy here for those who have low vitamin D status. It's always, of course, important to get enough sunshine and reduce exposure to vitamin D's antagonists, but this is a nice little backup plan.

Additional research in women published in 2022 also showed a synergistic combination of vitamin D and HMB.[64] What's great about this study is that the women who had enough vitamin D in the first place still responded well, further backing HMB's efficacy up since they didn't have a vitamin D deficiency to correct.

Dosage and Directions

The Vitamin Shoppe's website states to mix one (1) scoop with 10-12 oz. of water or your favorite beverage 30-60 minutes before or after your workout.

It's definitely worth noting that much of the HMB research was provided with a dose equivalent to two servings per day. While that will cost you twice as much, we're confident it would also lead to better results given the data at hand.

Conclusion: A part of BodyTech Elite's January 2024 Lineup

This is a solid supplement -- there's solid research combining creatine and HMB, yet we don't always see them used together as often as we'd like. We're happy to see The Vitamin Shoppe leaning into their BodyTech Elite Series with this.

However, that's not all BodyTech Elite's been up too -- if you follow PricePlow's BodyTech news, you may also see that they recently launched a few other products, including but not limited to:

- BodyTech Elite Altered Savage Pre-Workout

- BodyTech Elite Shredded Physique Fat Burner

- A new flavor of BodyTech Elite Altered Strength Pre-Workout

Looks like good things are coming, but back to this formula... you can basically never go wrong with creatine and myHMB.

BodyTech Elite Creatine + HMB – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)