We all want to stay active, and more specifically, to keep doing what we've always done in the gym. But two things can happen over time:

InnovaPharm Flexamend is a powerful anti-inflammatory joint support supplement with several clinically-validated ingredients

- We train aggressively and tend to push our muscles -- and thus joints -- to certain limits, sometimes damaging the latter in a quest to grow the former.

- We age. We may love lifting heavy when we're young, but the older we get, the harder it is to pull off without getting hurt.

Either way, the victim of our quest for gains often comes in the price of our joint health.

InnovaPharm Flexamend: Support Your Joints with Innovation

So, with that in mind, InnovaPharm has given us a very nifty joint support formula – Flexamend, which is absolutely jam-packed with powerful anti-inflammatory ingredients.

One thing we love about this formula is the abundance of randomized controlled trials backing the main ingredients.

So now after you blow it up with their incredible new pump supplement, Poppa Pump, your joints will need a bit of support to get back in there and do it again.

Let's get into how it works but first, check PricePlow for product pricing and availability, and sign up for our InnovaPharm news and deals, these guys have been innovating like crazy lately:

InnovaPharm Flexamend – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

InnovaPharm Flexamend Ingredients

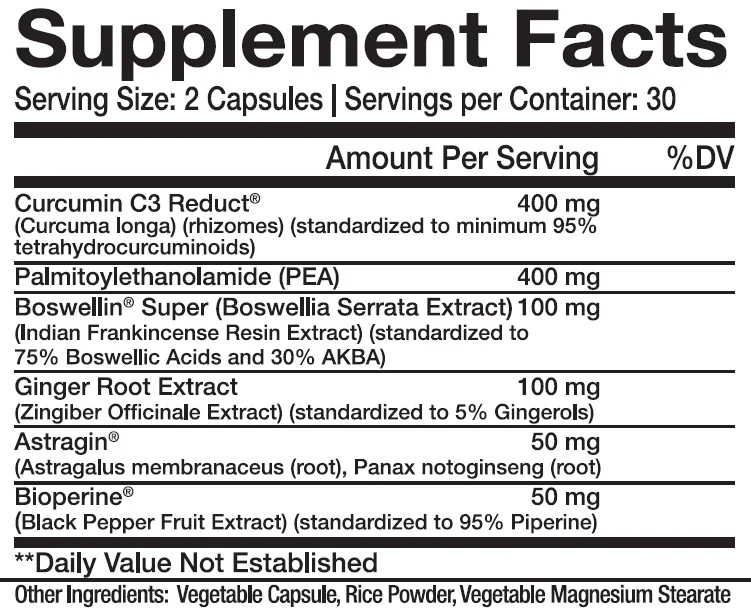

In a single 2 capsule serving of InnovaPharm Flexamend, you get the following:

-

Curcumin C3 Reduct (Curcuma longa) (rhizomes) (standardized to minimum 95% tetrahydrocurcuminoids) – 400 mg

Curcumin is a brightly colored orange pigment that gives turmeric its instantly-recognizable color.[1] The word "curcumin" most often refers to a particular molecule, but it's important to recognize that curcumin is only one in a large family of compounds called the curcuminoids. The curcuminoids as a whole are powerfully anti-inflammatory.[2] This is why turmeric root, which is rich in curcuminoids, has been employed for millennia by traditional medicine systems including Ayurvedic medicine.[3]

In addition to decreasing inflammation,[4-9] curcuminoids are also potent antioxidants.[1,10-15] This shouldn't surprise anyone, given the close connection between inflammation and oxidative stress.[16]

Inflammation and oxidative stress are powerful therapeutic targets, with lots of downstream benefits. Because of this, curcuminoids have been recognized by researchers for their ability to improve liver, cardiovascular, and neurological health.[17]

How curcuminoids downregulate inflammation – cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)

Just to put the power of the curcuminoids into perspective, these bioactive constituents have been shown to inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2),[18-21] a pro-inflammatory enzyme[22] that's also targeted by famous non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs aspirin and ibuprofen. Like these NSAIDs, curcuminoids have been shown to substantially decrease the severity of chronic pain.[4,9,14,23-33]

Curcuminoids and joint health

There are quite a few studies showing that curcuminoid supplementation can help improve the severity of osteoarthritis symptoms.[4,9,14,23-33]

In one of these studies, a randomized controlled trial, 500 milligrams of turmeric extract per day for 4 months decreased the incidence of joint crepitation by 60%, joint stiffness by 64%, and joint effusion by 76%.[34] In other words – just to be clear – of the patients who began this study with active knee crepitation, 60% of them saw it go into remission by the end of the study period.

Focusing on tetrahydrocurcumin

While we don't exactly have the above 500 milligram dose, we are quite close -- and this is no standard "turmeric extract" -- InnovaPharm selected a standardization of 95% tetrahydrocurcuminoids, highly-bioavailable metabolites that the body actually forms when you take curcumin orally.[35-38]

This "side-stepping" by taking the metabolite provides a few benefits, since you get more of the active ingredient inside. Of note, a few different pathways are more highly-targeted,[37] and there may even be some metabolic benefits![38]

Additionally, many brands and manufacturers appreciate that tetrahydrocurcumin is white,[39] and dieters enjoy that it combats harmful lipid peroxidation.[40] The latter of which, we're starting to believe, will support joint health as well. We'll take it all!

-

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) – 400 mg

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is a lipid molecule with demonstrated anti-inflammatory, pain-relieving, anti-microbial, immunomodulatory, and neuroprotective effects.[41] One really cool thing about PEA is that your body actually synthesizes it endogenously from palmitic acid, a type of lipid that occurs naturally in coconut oil, meat, and dairy products.[34]

But since your body only creates as much PEA as it needs at any given time, this means that it's almost always possible to derive additional benefit from supplemental, exogenous PEA. This is especially true if you're a vegan or vegetarian, as restricting animal product intake is likely to downregulate endogenous PEA production.

As of the time of this writing, PubMed has indexed over 350 peer-reviewed journal articles about PEA's benefits for human health. Some of these papers discuss the fact that PEA has been used as a medicine in many parts of the world – e.g., PEA has been used to in flu and cold patients,[34] has been identified as a possible therapy for irritable bowel syndrome,[42] and has also been studied for use in autoimmune and neurological diseases.[34,43,44]

When we see such diverse benefits, we think two things:

- It combats systemic inflammation

- It supports liver health

And that indeed seems to be the case in terms of inflammation: PEA's many applications and benefits share one thing in common – PEA's natural anti-inflammatory activity. One meta-analysis, published by the Journal of Pain Research, concluded that PEA is a viable therapy for managing chronic and neuropathic pain.[43]

A research review published by the same journal concluded that PEA supplementation is safe and effective for dealing with nerve compression syndromes like sciatica and carpal tunnel.[44]

The PEA mechanism of action: an endocannabinoid!

PEA downregulates inflammation by agonizing proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α), which signals your body to decrease its production of inflammatory cytokines.[43]

But what makes PEA really distinctive is its ability to active your body's endocannabinoid system,[43] which is responsible for the runner's high euphoria that can be triggered by vigorous exercise.[45]

The endocannabinoid system has also been studied for the management of arthritic joint pain. One study found that activating the endocannabinoid system may actually halt the progression of arthritis.[46]

This makes sense because endocannabinoids are themselves anti-inflammatory.[43,45,46] Furthermore, PEA can decrease the activity of mast cells, which play a central role in the inflammatory response.[47]

-

Boswellin Super (Boswellia Serrata Extract) (Indian Frankincense Resin Extract) (standardized to 75% Boswellic Acids and 30% AKBA) – 100 mg

Boswellia contains four different boswellic acids, the most powerful of which is called acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA). The boswellic acids, including AKBA, have been shown to exert potent anti-inflammatory effects.[48]

The boswellic acids, including AKBA, are known to downregulate an enzyme called 5-lipoxygenase (LOX-5),[49,50] which triggers the creation of toxic lipid peroxides from polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in a process known as lipid peroxidation. It's an extremely inflammatory process,[51-53] so decreasing LOX-5 activity is one of the most powerful anti-inflammatory mechanisms at our disposal.

As it turns out, boswellia is a great ingredient to pair with COX inhibitors like curcumin (see above) – combination COX and LOX-5 inhibitor compounds are known to be extremely good at downregulation inflammatory processes, and have been collectively identified as a serious contender to be the next-generation non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).[54] Needless to say, we're thrilled to see curcumin and boswellia show up together in InnovaPharm Flexamend.

Other research indicates that AKBA can decrease the body's production of inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).[55-57]

Management of osteoarthritis

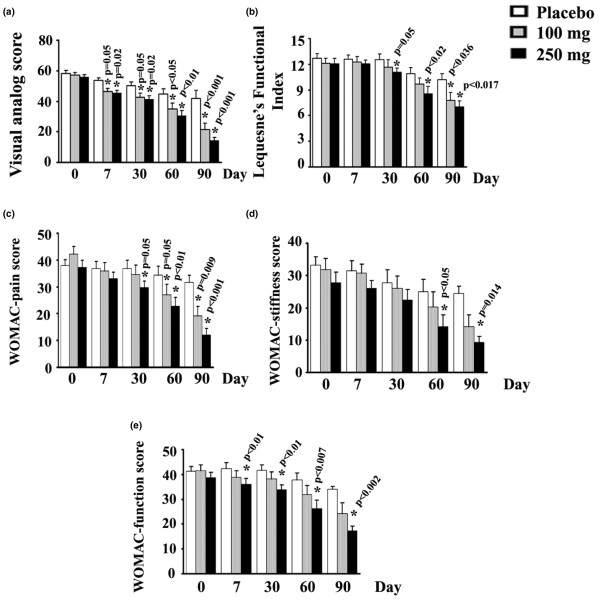

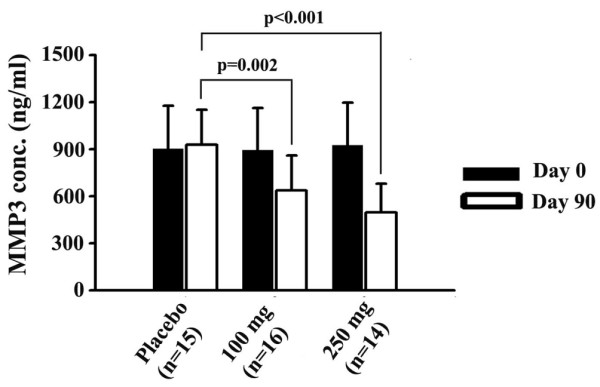

One randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that Boswellia extract can dose-dependently improve patient scores on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), an inventory designed to measure the intensity of knee pain.[58]

Study participants who took 100 mg or 250 mg of a standardized Boswellia serrata extract daily saw significant improvements in their scores on the WOMAC index, an inventory used to measure knee pain in osteoarthritis patients.[58]

The same study showed that the Boswellia extract can inhibit matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP-3), an enzyme that degrades collagen and tends to be overexpressed in OA patients.[58] Given that collagen is an important building block for joint tissue, it's not shocking that this mechanism would be implicated.

At least two other RCTS have shared similar findings.[59,60]

-

Ginger Root Extract (Zingiber Officinale Extract) (standardized to 5% Gingerols) – 100 mg

Ginger is a close relative of turmeric and, like turmeric, has impressive anti-inflammatory effects.[61,62]

Certain bioactive constituents in ginger, like its gingerols and shogaols, are known to decrease the production of proinflammatory cytokines like interleukins 1 and 8 (IL-1, IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). They do this through some mechanisms of action we've already discussed in this article – namely, LOX-5 and COX inhibition.[63,64]

One shogaol in particular, 6-shogaol, has been shown to downregulate inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme that generates NO in a stress hormone context,[65] as opposed to endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which generates the good, cardioprotective, vasodilatory kind of NO.

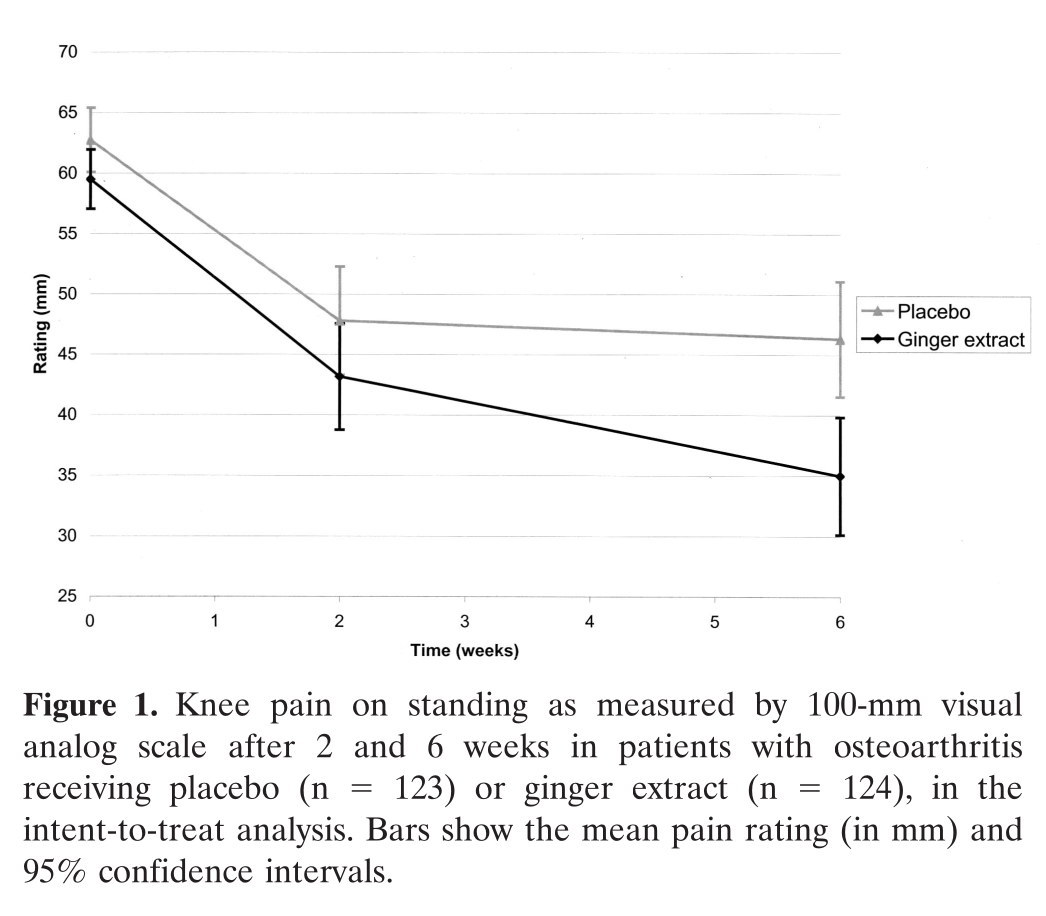

In a randomized controlled trial, OA patients who consumed ginger extract reported a significantly greater reduction in knee pain than the placebo group.[66]

One study showed that OA patients who randomly received either 255 mg of ginger extract, or a placebo, saw significant improvements in reported knee pain and WOMAC score by the end of the 6-week study period.[66] The effect sizes were pretty impressive – the ginger group saw an average 13 point reduction, compared to the placebo's 9 point improvement.[66] The ginger group also experienced substantially less knee pain when standing and walking 50 feet.[66]

-

AstraGin (Astragalus membranaceus (root), Panax notoginseng (root) – 50 mg

AstraGin is a patented[67-71] combination of botanical extracts sourced from Chinese ginseng and astragalus – two plants that are absolutely loaded with bioactive constituents that improve gastrointestinal function.

The bioactives in AstraGin have been shown to increase the amount of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) produced by human intestinal cells. Once those cells have access to the extra ATP, they can use that cellular energy to absorb more nutrients from the food and supplements that are passing through the digestive tract.

Thus, AstraGin is hoped to increase the bioavailability of whatever you take it with.

When taken regularly over long periods of time, AstraGin can even improve gastrointestinal health.[72]

-

BioPerine (Black Pepper Fruit Extract) (standardized to 95% Piperine) – 50 mg

Piperine, the primary bioactive constituent of BioPerine black pepper extract, is another bioavailability-enhancing ingredient like AstraGin. The key bioactive constituent here is piperine, an alkaloid that's been shown to inhibit the action of certain stomach enzymes. When those enzymes are less active, ingested nutrients are able to transit your stomach intact, thus increasing their absorption by the intestines.[35]

Piperine can also benefit metabolic health a bit – it's increases insulin sensitivity by activating glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4),[36] and can discourage the accumulation of fat in your liver.[37] It's also a powerful antioxidant.[38]

Incredible synergy with curcumin

So if BioPerine and AstraGin are both bioavailability enhancers, why do we need the two of them in the same formula?

As it turns out, piperine is unbelievably good at increasing the bioavailability of curcumin specifically. While curcumin is hamstrung by low oral bioavailability when taken on its own,[39] BioPerine has been shown to increase curcumin's absorption by an absolutely incredible 2,000%.[40]

Dosage and Directions

Take one serving once daily. There are many strategies with an anti-inflammatory supplement like this:

- 1 Capsule in the AM, 1 Capsule in the PM (12-hour shifts for the ingredients)

- Take before bed for improved sleep from the PEA

- Consider pre-workout if you have serious joint pain. Note, however, that this may reduce muscle inflammation, which we want when training, so this is our least-preferred method.

Conclusion: Potent Anti-Inflammatory for post Poppa Pump

The InnovaPharm Flexamend formula might be short, but it's also sweet. We have some really awesome synergy here, with multiple ingredients inhibiting LOX-5 and COX, plus the very smart inclusion of BioPerine in addition to AstraGin for the curumin-specific bioavailability boost.

In this formula, we also have three different ingredients – curcumin, boswellia, and ginger root extract – that have been validated as efficacious specifically for joint problems by randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. This type of study design is the gold standard in medical and nutritional research, so we always feel confident in a product that's based on RCT-backed ingredients.

If you're feeling seriously inflamed, there's no supplement we'd rather try first.

Overall, this is one of those products that illustrates how ingredient quality can be much more important than quantity.

InnovaPharm Flexamend – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)