POM Wonderful v. Coca-Cola - What was the big deal?

So you heard that Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals sued MusclePharm and Brad Pyatt over alleged amino acid spiking... or Nutrition Distribution LLC is suing IronMagLabs over "unfair competition".

How can one supplement company sue another one over each others' labels, when those allegations seem to be related to the FDA's jurisdiction, and not that of civil courts?

The answer to that question lies in The Lanham Act, and an important 2014 Supreme Court Decision the entire consumables market space.

Nutrition facts labeling is a serious issue, recently made even more serious

We live in a world where no one can fully escape liability. Companies of all sizes are constantly getting sued for something, and as the numerous laws and regulations mount, so do the capabilities of the lawyers.

Every once in a while, there's a game-changing legal case that's relevant to the sports supplement industry, which is often mistaken to be unregulated. By reading the headline, you still might be asking how a juice company suing the global leader in sodapop is relevant here in the supplement industry.

Mark Glazier explains that supplement companies are regulated, despite 'common' opinion. And after reading this post, you'll understand how competitors and lawyers have another tool in their chest.

It turns out that this case has everything to do with the supplement industry, and affects every company that is selling consumable products in the U.S. marketplace.

When POM Wonderful decided to sue Coca-Cola, things escalated to the point where the United States Supreme Court had to decide how far civil laws could go, and essentially ruled that companies can sue competitors for misleading advertising, specifically under the Lanham Act.[1]

POM Wonderful vs. Coca-Cola: A quick primer

It helps to give a quick background. The summary of the issue is that POM Wonderful (the company that makes those well-known, antioxidant-packed bottles of pomegranate juice) went after Coca-Cola for “deceptive labeling”.

Coca-Cola-owned Minute Maid had a product it called a “blueberry pomegranate juice”, and POM believed it was blatant false advertising, because Coca-Cola's drink contained only 0.5% pomegranate and blueberry juice. Basically, POM believed Coca-Cola’s “falsely advertised drink” was damaging POM’s “properly and accurately” advertised product, which had more active pomegranate constituents.

In 2014, we captioned this image with "The supreme court recently ruled that Pom Wonderful may sue Coca-Cola, their competitor, for anti-competitive label claims. Will that decision affect the supplement industry?" -- The answer to that question was clearly YES.

After a long-drawn out legal battle spanning the greater part of a decade, two things happened:

-

The United States Supreme Court ruled that POM was allowed to pursue a legal suit against Coca-Cola under the Lanham Act,

-

POM Wonderful ultimately lost their suit multiple times in the 9th Circuit court of appeals.[2,3]

POM Wonderful ultimately lost, but they won the ability for these civil suits

It's the first of those two points that matters to everyone with a consumable product bearing a nutrition label. This case blew off the door to allow supplement companies (and any other type of food/nutrition/supplement company) to sue competing companies for deceptive and misleading labeling on their products -- if it legitimately interferes with the company's interests.

Here's an example:

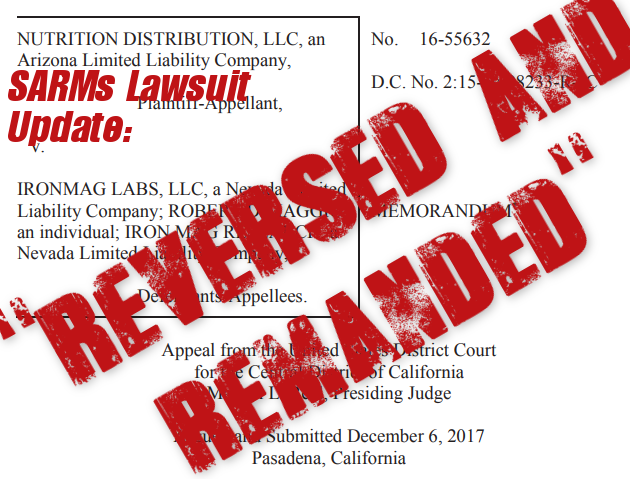

Nutrition Distribution vs. IronMagLabs has gotten crazy, and their Enhanced Athlete lawsuit has gotten even crazier. Now that the FDA has weighed in, the appeals court is allowing Nutrition Distribution to try this one again, but with some restrictions

Imagine that Supplement Company A makes a protein product and then one year later, Supplement Company B makes a similar protein product. If Supplement Company A’s product would be diluted because Supplement Company B’s product is falsely advertised, deceptive, or mislabeled, and therefore Supplement B’s company would confuse consumers about Supplement Company A’s product, then the Supreme Court has decided that Company A could sue Company B.

What is The Lanham Act?

The Lanham Act has been around for over seventy years. In this instance, it protects product owners and companies against false advertising that could harm the reputation of its own product.[4]

The provision POM relied on allows one competitor to sue another if it alleges unfair competition arising from false or misleading product descriptions.[1] The entire point of the act is to make deceptive practices of using marks be punishable.

What Went Down With POM and Coca-Cola

Basically, POM sued Coca-Cola under this piece of legislation, because it believed Coke’s “Pomegranate Blueberry” flavored drink was misleading consumers and that Coke’s “misleading” drink would ultimately affect the public perception of POM’s juice in a negative light.[1] (Coca-Cola’s drink contained only 0.5% pomegranate and blueberry juice and so it was argued that this product, potentially being less "effective", would damage the entire 100% pomegranate juice market).

Simple enough, right? It seemed that way.

At first, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals said that the Lanham Act could not be used in this capacity, as they argued that labeling concerns were under the FDA's purview.[2] However, POM appealed up to the United States Supreme Court, who then reversed that part of the decision, and ruled POM could in fact sue Coca-Cola for misleading advertising - specifically under the Lanham Act.[1]

Essentially, win or lose (and POM did indeed end up losing), the SCOTUS decision set precedent for other companies to sue competitors for those same kinds of reasons.

Open season? In the litigious supplement industry... of course!

This means open season for any company who wants to bring a lawsuit against another company for false advertising, deceptive claims, or inaccurate labels. What makes this ruling so significant, is that now companies and manufactures in an unregulated industry can sue others for false advertising!

We can think of plenty of supplement companies who had been licking their chops to get some similar lawsuits filed against other companies - and many of these cases are still going on, and only getting crazier and crazier (stay tuned for the entire story on the Enhanced Athlete situation).

POM’s Victory Has Far Reaching Impacts

So in POM v. Coca-Cola, the Supreme Court remanded the case back down to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2014.[1] This means that the case went back to the original court and was essentially re-tried, only this time, the original court had to allow POM to proceed with its suit under the Lanham Act (Coke argued from the get-go that POM couldn’t sue under the Lanham Act, so that was the issue went all the way up to SCOTUS)

Fast forward to March 2016 when the suit was retried, a jury determined that Coke’s juice was acceptable, even under the Lanham Act.[3] A bummer for POM, but it still won a monumental battle on behalf of the food and beverage industries.

The 2016 decision doesn't really matter to most of us, but the 2014 SCOTUS one does - POM’s fight established other companies ability to bring civil suit against competing companies under the Lanham Act.

What Does This Mean For The Supplement Industry?

Depending on how you look at it, the POM v. Coca-Cola decision is a major win for many manufacturers in the food and beverage industry - and definitely a win for lawyers who now have another tool in their arsenal. The SCOTUS decision translates directly to the supplement industry, which is often argued to be particularly misleading regarding how some companies decide to advertise or label their products.

Considering lawsuits are commonly brought by competitors, the SCOTUS ruling in POM v. Coca-Cola will give companies and manufacturers the ability to legally “call out” competitors who may be mislabeling products or false advertising.

Amino spiking, dangerous ingredients, false claims of effectiveness, companies who aren't lab testing their raw materials, etc... the list goes on. In order to win, the accusers will need a leg to stand and prove that they have been harmed in some way, but the floodgates are officially open and it did not surprise us to see a flux of lawsuits.

On the other end, companies have lost some protection by the POM v. Coca-Cola outcomes. The United States Supreme Court has set precedent that a similar claim (such as POM’s against Coca-Cola) will be sustainable under the Lanham Act - so something that was once considered to be only under the FDA's jurisdiction can now be tried in civil court.

The lawyers are watching: Better check that label and lab test that lot

We've always lived in a war of words between supplement companies. But now, when it comes to actual claims on the label, competitors (and their lawyers) have an extra tool in the chest, and it's pretty clear they're willing to use it.

This means that all companies need to proceed with extreme caution moving forward, especially if they manufacture a supplement with vague or misleading content claims, or don't bother to lab test their supplements, as we see occasionally from "time to time". Because any false labeling or false advertising will have potentially severe consequences, and there are lawyers and companies just waiting to strike.

The cycle never ends and likely never will. In the meantime, we as the consumers get to sit back and enjoy the fireworks, and pray that this ends up cleaning up the industry and not debilitating it.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)