Over 2,000 years ago the ancient Greek physician, Hippocrates — namesake of the Hippocratic oath — wrote, "All disease begins in the gut."

Probably radical for its time, especially considering that Hippocrates is considered to be the founding figure of medicine.

Gut Supplements: Prepare to meet the Ultimate Gut Health Supplement Stack by Revive MD - the fiber shown here is just one of five supplements!

Modern ultra-processed foods are ruining our gut health

Given the ultra-processed nature of the standard American diet (aptly referred to by its acronym, SAD), it's not a surprise to many people in the know that gastrointestinal illness is increasingly common in the United States.

Unfortunately, digestive disorders are also fairly common -- at least 11% of the US population suffers from one.[1] This number is likely a lot higher, though, because researchers have found that inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS), the most common digestive disorder in the US,[2] goes undiagnosed in more than 75% of those afflicted.[3]

As of 2018, we've reached the point where a whopping two-thirds (over 60%) of Americans are suffering from at latest one digestive disorder.[4]

As the incidence rates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity continue to climb, it seems more certain that the ancient wisdom of Hippocrates is evermore vindicated with each passing day.

Our strategy is two-fold: 1. Remove the insults (generally ultra-processed foods with inflammatory seed oils), and 2. Feed your gut the weapons it needs to keep you healthy

This state of affairs is both shocking – and unnecessary.

Remove seed oils, repair the damage

We at PricePlow are constantly begging readers to eliminate the most blameworthy culprits for digestive disease — the omega-6-laden "seed oils" (erroneously labeled as "vegetable oils") that are responsible for the biggest increase in Americans' excess calories over the last 50 years.[5,6] They're extraordinarily pro-inflammatory[7] and studies have demonstrated how they wreck the human gut microbiome.

Thankfully, many of you listened and removed these rancid oils from your diet, and reported great benefits from doing so.

But sometimes, when the damage is already done, you may still need some help getting back to optimal health.

A gut health stack to fight back with

Whether you're someone with a compromised gut, or someone with a healthy gut who just wants a good insurance policy against future disease, this is where the Revive MD Gut Health Stack comes in.

Today we're going to highlight five phenomenal supplements formulated by Revive MD—every single one can provide substantial, complementary contributions to your efforts at regaining or maintaining the health of your digestive tract.

If you want to read our in-depth write-ups of these products, follow the links below:

- Revive MD Fiber: A Fiber Supplement with the Best of Both Worlds

- Revive MD GI+: A Gut Health Supplement That Does More

- Revive MD Probiotic: Boost Your Healthy Gut Flora

- Revive MD Digest Aid: Digestive Enzymes to Beat the Bloat

- Revive MD Glutamine: Why Add to Your Gut Health Stack

- Revive MD Gut Health+: Target Harmful Bacterial Overgrowth

If your gut's in a seriously bad way, this stack attacks it from multiple angles - including repair and regrowth - and can help you better digest your food moving forward. We've never seen a brand focus so heavily on a problem, but it's a problem worth attacking aggressively -- which does require quite a few supporting ingredients.

Read on for a condensed summary of the product line below. It all starts with fiber:

-

Revive MD Fiber

Fiber is a generally indigestible type of carbohydrate[8] that's crucial for human digestive health. Basically there are two different kinds of fiber:[9]

- Soluble fiber: occurs naturally in foods like fruits and vegetables

- Insoluble fiber: occurs naturally in foods like cereal grains

The individual requirements for fiber vary a bit, based partly on the individual's diet, but also on the optimal amount recommended by nutritional authorities (which was developed and based on legitimate differences in health and diet research). But for people eating a "standard" macro split with plenty of carbs, it's generally agreed that men should aim to consume somewhere between 30 and 35 grams of fiber per day, and women 25 to 32 grams daily.[10]

Why Fiber?

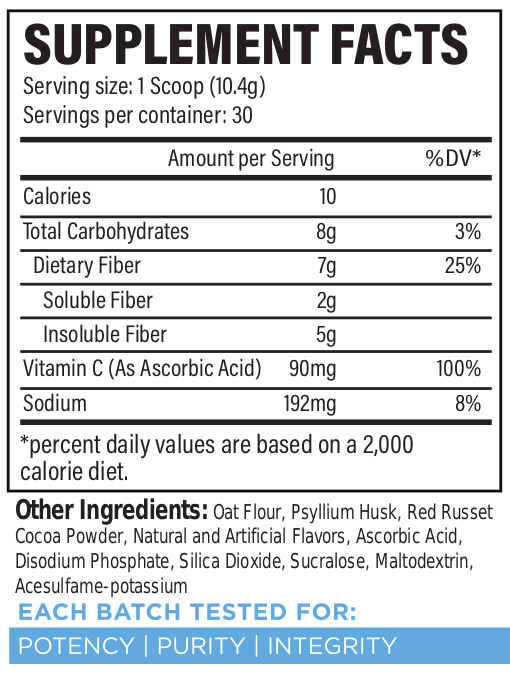

Introducing Revive MD Fiber, which has both soluble and insoluble fiber, and comes in a delicious chocolate flavor!

You could write a whole thesis on fiber and its advantages. In 2020 there was a great article published in the journal Nutrients titled "The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre"[11] Here's a brief summary of those benefits:

- Increased gut motility (ability to eliminate waste) and less constipation[12]

- Leaner body composition, especially when it comes to abdominal fat[13,14]

- Better insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health[15]

- More diverse and healthful microflora in the gut[16]

- Lowered levels of inflammation[17,18]

- Slightly elevated mood[19]

- Decreased risk of cardiovascular disease[20,21]

- Decreased risk of colorectal carcinoma, a specific type of cancer called[22,23]

- Less mortality[24]

The main mechanism that mediates all of these benefits is dietary fiber's ability to help the body produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)[25,26] that, by acting as a highly available fuel source for intestinal cells, help tamp down inflammation[27] and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO),[28] an amine oxide that has been linked to cardiovascular disease.[28]

So, as you can see, there are a lot of strong arguments for including fiber in your diet. But one of the biggest complaints about getting 30 grams of the nutrient per day from whole foods is that it's pretty difficult.

That's where Revive MD Fiber comes in. This unique fiber formula consists primarily of two ingredients: oat flour and psyllium husk:

-

Oat flour (from oat hull fiber)

This is an interesting inclusion because the vast majority of fiber supplements on the market consist more or less entirely of psyllium husk. But we really like oat flour due to some unique components—and unique benefits.

Oat hull fiber (a highly insoluble fiber that provides glycemic benefits)

According to Revive MD CEO Matt Jansen, one benefit of using oat hull fiber is that it allows the company to increase fiber content while keeping the digestible carbohydrate content fairly low.

Oat hull fiber is highly insoluble,[29-31] as much as 95% insoluble, according to one estimate.[31] And it's not fermented as much in the gut compared to psyllium.[29] Since psyllium is a soluble fiber, the oat flour in Revive MD's fiber supplement ensures you've got both of your fiber bases covered: soluble and insoluble. That's impressive because most fiber supplements consist of only one type — rarely both.

In the research literature, oat hull fiber intake among women has been associated with lower levels of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c),[30,32] a biomarker whose blood levels correlate with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. The effect seems to be especially and specifically pronounced in those who have high levels of fasting glucose.[30,33]

Other benefits of oats

Oats have long been recognized for their high content of vitamins, minerals and unique bioactive constituents like β-glucan, a type of polysaccharide carbohydrate with benefits for human metabolic health.[34,35] Among other things, β-glucan beneficially impacts a person's blood cholesterol profile,[34,35] and is probably responsible for oatmeal's notable ability to do the same.

Oats also contain high levels of avenanthramides—polyphenols with nitric-oxide (NO) boosting properties that reduce inflammation and itching.[36,37]

-

Psyllium Husk

Also known as Plantago ovata, Plantago psyllium has fibrous husks that supplement users are familiar with as psyllium husk fiber. This is one of the key ingredients that for decades has been used in daily fiber supplements, and for good reason—there's a wealth of information and research on it!

Psyllium husk fiber primarily consists of a polymer called arabinoxylan, which is composed of arabinose and xylose, which the human digestive system won't sufficiently digest.[39] As opposed to our oat hull fiber, psyllium is highly water soluble—it's slow-fermenting and actually forms into a gel when mixed with water.[29,40,41]

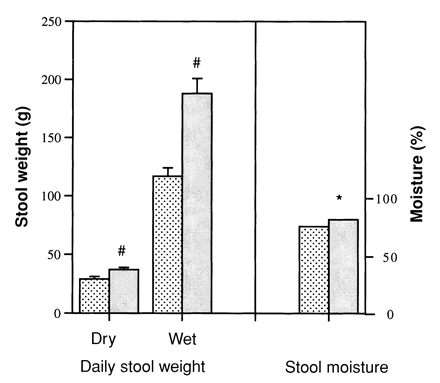

Psyllium as a bulk laxative (increasing stool weights)

Psyllium has been used as a bulk laxative coming on 50 years[42] -- this is a special type of laxative that increases fecal weight and stool size[38,42-44] by reacting with gas and water in the digestive tract.[45] This makes psyllium a kind of "digestive adaptogen"—it hardens stools that are too soft and softens those that are too hard.[46] The upshot in both cases is stools that are easier to pass[47,48] when they're too hard, yet reduced rates of diarrhea when they're too soft![46]

Psyllium and gas reduction

In one study by gastroenterology experts at the University of Michigan, researchers determined that volunteers who consumed 30 grams of psyllium daily had significantly less flatulence as a result.[49] It's important to note this because some types of fiber can actually worsen gas, so we want to be sure to specify that psyllium is not one of them.

Psyllium and appetite reduction

According to some research, using psyllium husk can substantially reduce appetite, especially three to six hours after taking it.[50-52] Note that these studies used fairly large doses of psyllium — between 10 and 20 grams per serving -- which is indeed more than we have in a single serving of Revive MD Fiber, especially since it's sharing some space with the oat fiber. We point this out because you'll probably need more than the recommended dose to achieve that same effect.

There's a bit more fiber coming into the stack below, too, but Revive MD Fiber is a great way to get both soluble and insoluble fiber in:

Revive MD Fiber – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

-

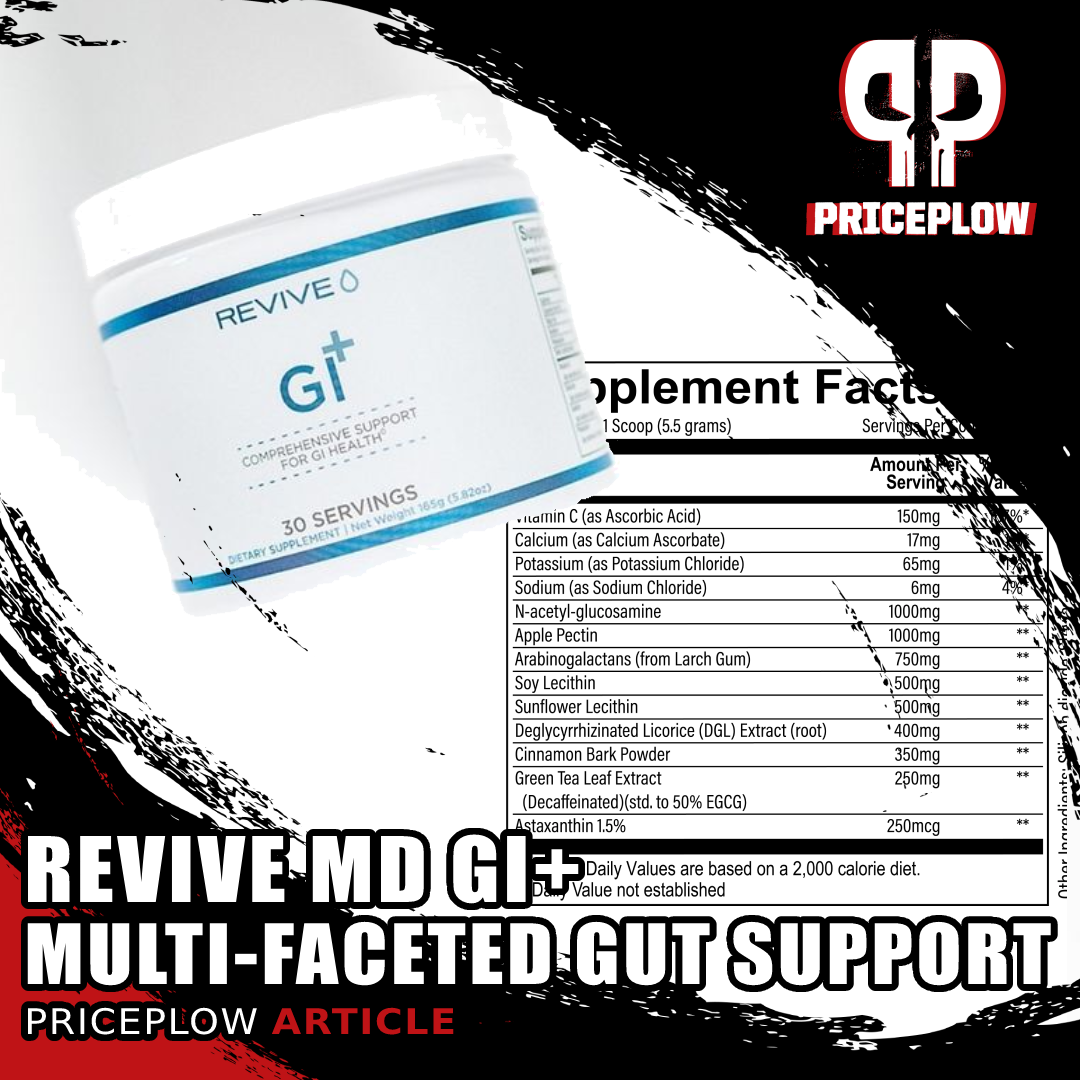

Revive MD GI+

GI+ from Revive MD is a formula focused on lubricating the gut by encouraging optimal mucus production, increasing the production of beneficial gut microflora, promoting gut immunity, as well as repairing the lining of the gut to make sure it's not permeable to undigested food.

Revive MD, a supplement brand that's no stranger to all-in-one formulas, has put out their comprehensive GI Health supplement, GI+

This is a very unique gut health restoration supplement that's quite unlike anything we've seen, so let's dive into it:

-

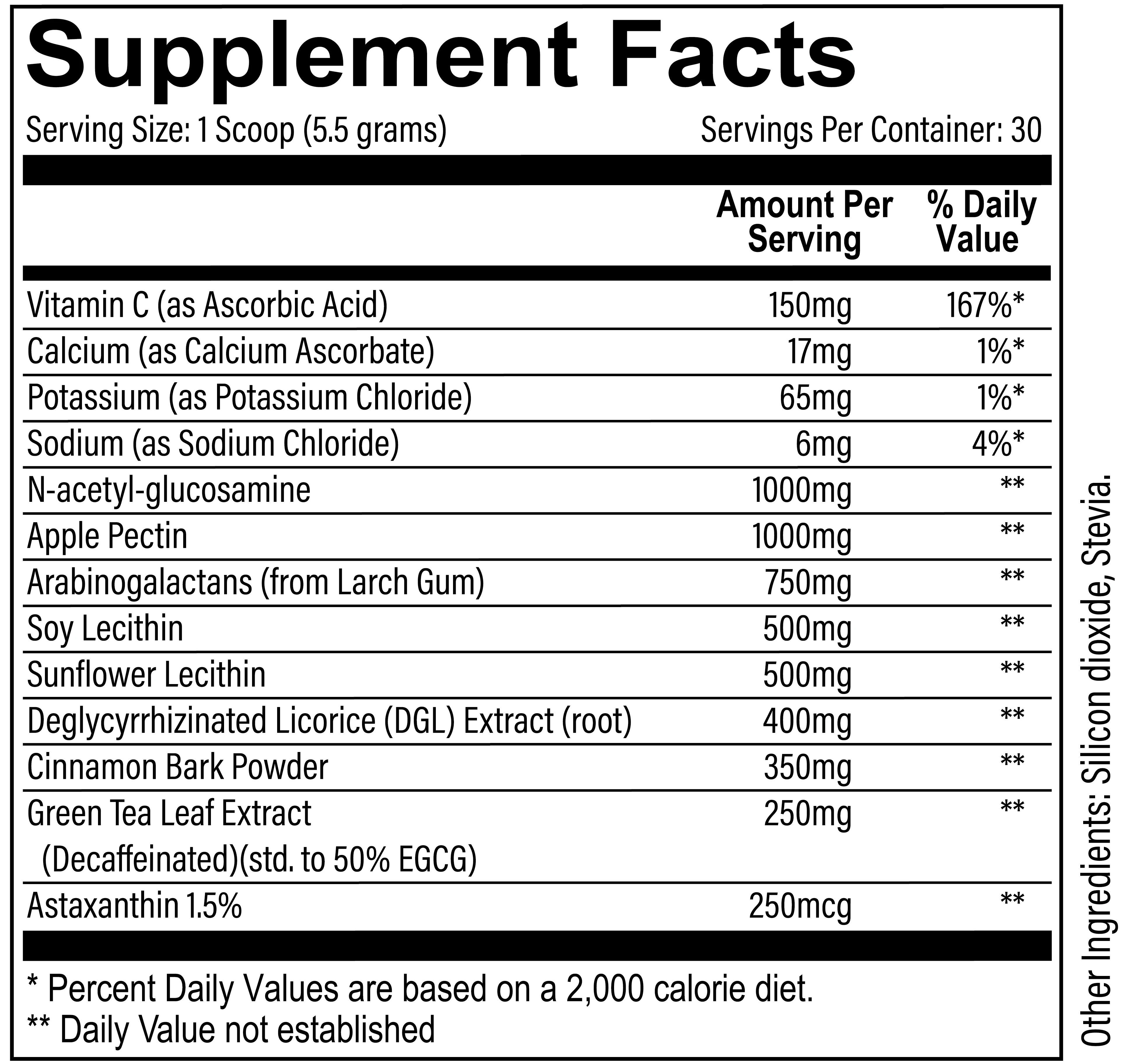

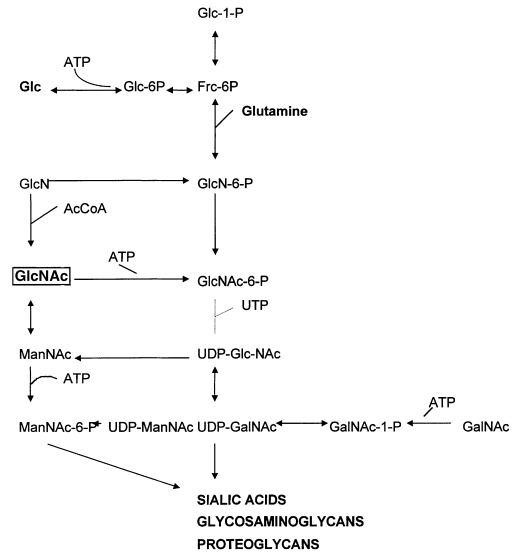

N-acetyl-glucosamine - 1000mg

Glucosamine is commonly found in joint supplements because of its ability to reduce joint pain and support joint integrity.[53,54] And there's this: a 2020 study found that people who take glucosamine supplements have longer lifespans. The nutrient, according to researchers, seem to be responsible for lower levels of all-cause mortality.[55]

The reason that glucosamine has these properties is collagen, which is important not only for joint health but also for the integrity of the digestive tract. It's largely composed of N-acetyl-glucosamine.[56] Since 1977, researchers have known that glucosamine synthetase, the enzyme that initiates the synthesis of N-acetyl-glucosamine, is down-regulated in people with Crohn's disease.[57]

So in 2000, researchers conducted a pilot study, published in the journal Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics,[58] that examined the question regarding whether N-acetyl-glucosamine could alleviate GI disease symptoms in patients who weren't responding to conventional treatments. 12 children, 10 with Crohn's and 2 with ulcerative colitis, were given 3 to 6 grams of oral N-acetyl-glucosamine daily.

Of the 12 children in this study "with severe treatment-resistant inflammatory bowel disease," eight recovered and were able to cease treatment for their condition.[58]

Although this was a small study, it's widely cited because of the almost miraculous effect that the N-acetyl-glucosamine had on diseases that are widely perceived as intractable.

-

Apple pectin – 1000 mg

Sometimes, you just have too many ingredients to do it in a capsule. At 5.5g dosage, it has to be in a powder!

Apple pectin falls into a fiber category called prebiotic dietary fiber, defined as "a nondigestible compound that, through its metabolization by microorganisms in the gut, modulates composition and/or activity of the gut microbiota, thus conferring a beneficial physiological effect on the host."[59]

According to a review published by the journal, Current Developments in Nutrition, prebiotic fiber intake is associated with the following outcomes:

- Increased levels of beneficial microflora (bacteria) in the gut[60]

- Better calcium absorption[60]

- Higher production of health-promoting metabolites[60]

- Better immune function[60]

- Better gut barrier integrity[60]

- Lower risk of allergies[60]

- Less fermentation of dietary protein in the gut[60]

In the gut, pectin combines with water to become a gel,[61] which helps to normalize stool.[62] Some studies have shown that high doses of pectin can help alleviate symptoms of both diarrhea and constipation,[63,64] making it what we consider to be another "digestive adaptogen".

It may also improve symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[65]

Additionally pectin satiates and may reduce hunger.[66]

-

Arabinogalactans (from larch gum) - 750mg

Arabinogalactan is a complex carbohydrate that occurs naturally in larche trees. A form of dietary fiber, it can actually improve immune function and help the body fight off infections. It consists of the sugars arabinose and galactose, which is where the name comes from.[67]

Arabinogalactan helps produce butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that helps support digestive tract health. It works by acting as an energy source for cells in the colon and stomach.[68,69]

-

Sunflower Lecithin - 500mg

Lecithin in its various forms is great for improving nutrient delivery, specifically those that are hydrophobic (not water soluble) and fat soluble. By improving the dispersion of fat-soluble nutrients throughout intestinal fluids,[70] this ultimately increases their bioavailability.[71]

-

Deglycyrrhizinated Licorice (DGL) Extract (root) - 400mg

Simplified summary of the central role of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) in the metabolism of the amino sugars.[58]

The flavor we know as licorice is sourced from Glycyrrhiza plants and has long been used as a folk remedy for lots of digestive ailments. However, one of its primary bioactive components, glycyrrhizin, consistently raises cortisol levels[72,73] and lowers testosterone levels[74,75] in people who take it—not something we want!

That's why Revive MD uses deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL), which is just licorice stripped of its glycyrrhizin.

With glycyrrhizin out of the picture, we can enjoy the bonuses of licorice supplementation — better digestion and reduced reports of nausea,[76] lower levels of H. pylori,[77] and fewer ulcers[78] — without compromising hormonal health in the process.

The documented benefits of DGL consumption include:[79-81]

- Better circulation to damaged gut mucosa

- Higher number of mucus-producing cells

- Increased mucus production

- Extended lifespan for intestinal cells

-

Cinnamon Bark Powder - 350mg

Although cinnamon is typically associated with glucose disposal supplements, it also has some uses for promoting gut health. One 2016 study showed that when pigs were fed cinnamon, they secreted less gastric acid and pepsin, which helped "cool" their stomach.[82]

-

Green Tea Leaf Extract (Decaffeinated)(std. to 50% EGCG) - 250mg

Green tea and extracts thereof are pretty close to a "silver bullet" in the supplement science world, with powerful applications in a wide range of domains.

It turns out that green tea can be good for your gut, too:

In a 2019 study conducted by the Human Nutrition Program at Ohio State University, researchers found that green tea consumption positively affected the population of bacterial microflora in human intestines,[83] thereby helping maintain the integrity of the intestinal wall and reducing leaky gut incidence.

Many studies have shown that green tea can improve the digestive process as a whole,[84] which is believed to be mostly due to its effect on gut flora.

Green tea also has some components that can improve food allergy symptoms by inhibiting the activation of Th2 immune cells.[85]

-

Astaxanthin 1.5% - 250mcg

Astaxanthin is a pigment that occurs naturally in salmon and other seafood, and confers a variety of health benefits by reducing oxidative stress. It does this by upregulating a process called autophagy, which is the body's mechanism for recycling dead or damaged cells and replacing them with new ones.

Astaxanthin helps boost secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA)[86,87] an immune compound that's found abundantly in the human gut's mucus lining, also known as the mucosa. Improving mucosal health can improve the integrity of the gut wall, preventing the pro-inflammatory leakage of undigested food — a phenomenon known as "leaky gut."

Promoting the health of the gut mucosa has other knock-on effects. In one 2008 study, astaxanthin substantially improved heartburn symptoms[88] in people infected with H. pylori, the bacterium that's been identified as the causative agent in stomach ulcers.

This is one of the most unique gut-restoration supplements we've seen. We had covered glucosamine numerous times in terms of joint health - but never N-acetyl-glucosamine in terms of gut health!

Revive MD GI+ – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

-

-

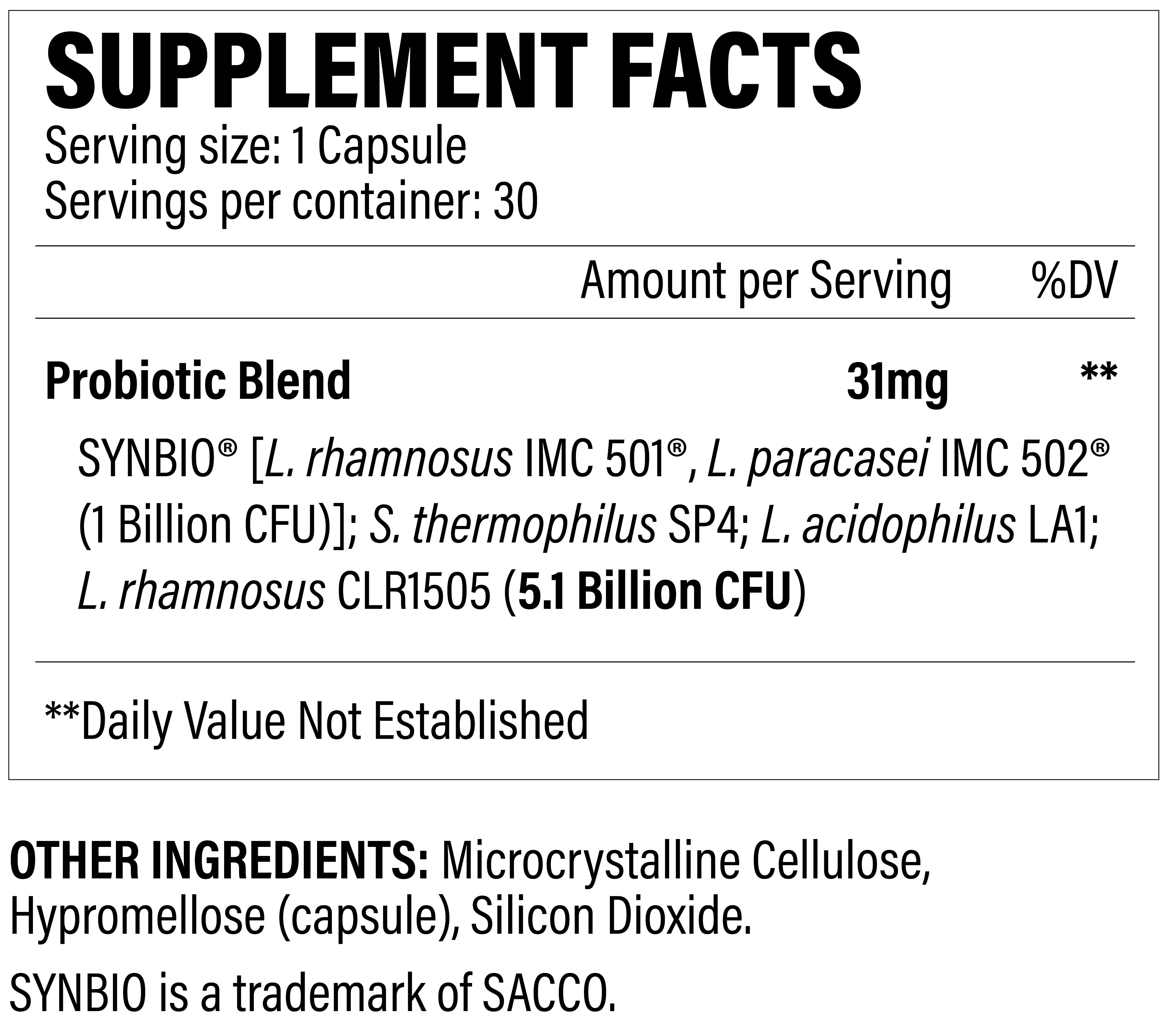

Revive MD Probiotic

Gut flora health has also become a major focus as of late. As researchers have increasingly begun to understand the "gut-brain axis" and its implications in mental health[89,90] and whole-body inflammation[90] -- in addition to overall immunity[91] -- we've begun to understand the importance of keeping the gut microbiome healthy.

There's even such a thing as the gut-muscle axis![92]To promote a healthy gut microbiome, supplement companies began selling probiotics, which are live organisms that support beneficial bacterial growth. There are hundreds of probiotics on the market, and in formulating theirs, Revive MD chose some patented probiotic blends.

Revive MD Probiotic is a rather aggressive formula, because it doesn't just support healthy bacterial colonies -- it attacks detrimental ones as well!

-

SYNBIO (L. Rhamnosus IMC 501 and L. Paracasei IMC 502) – 1 billion CFU

Not all probiotics are only for boosting healthy gut bacteria - some can attack detrimental colonies as well!

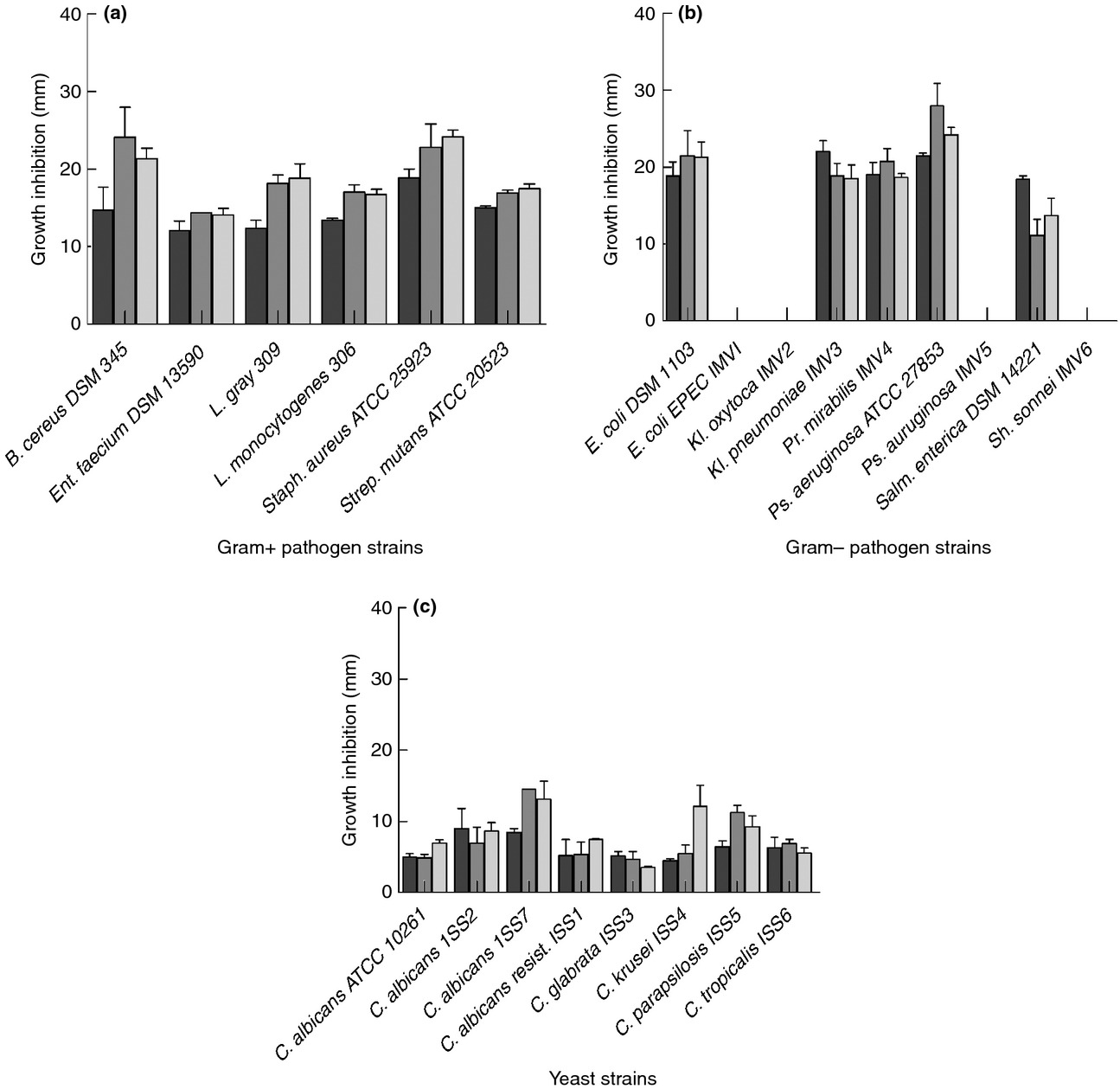

SYNBIO is a patented blend of two species from the important Lactobacillus genus that have been studied to out-compete more harmful bacteria.[93] It's been shown to inhibit several pathogenic gastrointestinal species tested, as shown in the chart below:

The inhibitory activity of IMC 501 (dark), 502 (gray), and the combination of both (SYNBIO, light gray) against various pathogenic species of yeast and bacteria.[93]

This is a very unique way to formulate a probiotic - by starting on the offensive, as opposed to the "defensive" approach that most supplements utilize.

-

S. thermophilus SP4

Additionally, Streptococcus thermophilus is a probiotic genus that's had success in fighting colorectal disease.[94] There are numerous immune system benefits to this strain, with animal models showing that S. thermophilus can significantly lower reduce inflammation biomarkers compared to controls.[95]

-

L. acidophilus LA1

Another bacterial strain from the Lactobacillus family is L. acidophilus LA1, shown to have numerous digestive system benefits. Again, we have another strain that can inhibit the ability for pathetic bacteria to function properly in the digestive tract.[96]

Research showed that LA1 actually prevented bad bacteria from binding to the digestive tract's cells by binding to them itself![96] It protected against Caco-2 cell adhesion and cell invasion against numerous diarrheagenic bacteria, providing support against both salmonella and E. coli, amongst others.[96]

-

L. rhamnosus CLR1505

Another form of Lactobacillus, L. rhamnosus CLR1505 has been shown to have some wildly impressive immunological benefits in animal models. For instance, researchers infected mice with S. pneumoniae (a bacterium that causes pneumonia) -- but the ones who were pre-treated with L. rhamnosus had improved T-cell counts, helping to support the pathogenic defense![97]

Additionally, L. rhamnosus strains can improve inflammatory biomarkers in blood tests.[98]

-

ReviveMD Digest Aid

As we learned in high school biology class (though most of us probably don't remember), an enzyme is a protein that accelerates (catalyzes) the chemical reactions that occur inside organisms. All living things produce and make use of enzymes.

Revive MD Digest Aid is an incredibly well-curated digestive enzyme blend to help you get the most out of your food.

Of all the enzymes in the human body, digestive enzymes are among the most crucial.

A digestive enzyme helps break down food molecules into their basic building blocks, which can then be absorbed by the intestine and transported into the bloodstream where they're delivered to tissues for the purposes of energy, growth, and repair.[99]

In the words of one paper published in 2016: "Enzymes control all metabolic processes in [the] human system from simple digestion of food to highly complex immune response. Physiological reactions occurring in healthy individuals are disturbed when enzymes are deficient or absent. Enzymes are administered for normalizing biological function in certain pathologies."[100]

Human digestive enzymes are synthesized mostly by the stomach and the pancreas,[99] which is why patients with pancreatic disease are often treated by means of supplemental digestive enzymes.[101]

Enzyme supplements as clinical therapy

In one small study from 2011, IBS patients took pancrelipase (PEZ) supplements, a cocktail of enzymes that are produced by the human pancreas. The PEZ was shown to alleviate some symptoms of pancreatic disease, such as cramping, bloating, and diarrhea.[102]

In another study where IBS patients were given a wide variety of digestive enzymes and prebiotic fiber, the combination of enzymes and fiber was shown to reduce bloating, gas and stomach pain.[103]

In dyspeptic patients, those who suffer from a cluster of symptoms including flatulence, bloating, and burping without a clear medical etiology, digestive enzyme supplements were, once again, found to improve their symptoms.[104] In the conclusion to that study, published in the "Journal of Medicinal Food," the researchers wrote:

"Overall, our results are in agreement with findings of previous studies, wherein significant efficacy was demonstrated by multienzyme preparations in alleviating frequency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms and patients had shown better tolerability."[104]

Enzyme deficiency is bad

Let's talk about what happens in cases of clinical enzyme deficiency.

Growing muscle requires a lot of food, and Revive MD Digest Aid helps your body break down and absorb even more nutrients!

Most of the time, it's caused by a type of pancreatic dysfunction that prevents the pancreas from making enzymes. When this happens, digestion basically fails, and afflicted patients are at major risk for serious deficiencies in almost every micro- and macro-nutrient,[105] from antioxidants to fat-soluble vitamins. As a result, they also have a seriously elevated risk for many major diseases, including sarcopenia and cardiovascular events.[105]

In this patient population, pancreatic enzyme therapy (PERT) has been shown to improve digestion to the point that these nutritional deficiencies can be solved.[105]

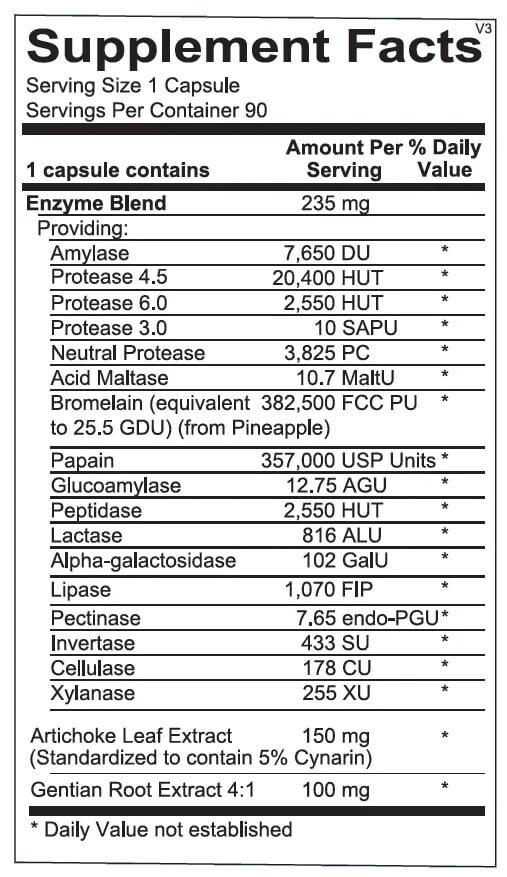

In a single, one-capsule serving of Digest Aid from Revive MD, you get:

Enzyme Blend - 235 mg

There are tons of digestive enzymes in Digest Aid.

Digest Aid contains a huge variety of digestive enzymes. The naming convention for major enzyme categories is simple: it's assigned by the substrate of the enzyme (i.e. the type of molecule) that the particular enzyme breaks down, followed by -ase, which is a suffix that denotes an enzyme.

For example, if a patient is lactose sensitive, it's sometimes treated with lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose (with varying levels of success for lactose). Protease breaks down protein and lipase (think liposuction or lipid) breaks down fat.

The enzymes and other ingredients contained in Digest Aid include:

- Amylase (7,650 DU): helps break down starch into simple sugars.[106,107]

- Glucoamylase (12.75 AGU): works synergistically with amylase.[108]

- Protease (22,950 HUT): helps break polypeptides into amino acids.[109,110]

- Peptidase (2550 HUT): helps break polypeptides into amino acids.[111]

- Maltase (10.7 MaltU): breaks down maltose,[112] a sugar that occurs in food additives.[113]

- Bromelain (25.5 GDU): helps digest protein,[114,115] improves knee pain[116] and allergy symptoms.[117]

- Papain (357,000 USP): helps digest protein.[118]

- Lactase (816 ALU): breaks down lactose,[119] improves lactose tolerance.

- Alpha-Galactosidase (102 GalU): breaks down glycosphingolipids and glycoproteins.[120]

- Lipase (1,070 FIP): breaks down dietary fat.[121,122]

- Pectinase (7.65 endo-GPU): breaks down pectin, a plant-derived polysaccharide.[123]

- Invertase (433 SU): breaks down sucrose (table sugar) into glucose and fructose.[124]

- Cellulase (178 CU): breaks down cellulose, a plant fiber.[125]

- Xylanase (255 XU): breaks down xylan, a cellulose-like polysaccharide.[126]

- Artichoke leaf extract (150 mg): provides digestive support.[127]

- Gentian root extract (100 mg): provides digestive and antioxidant support[128,129]

Revive MD Digest Aid – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

-

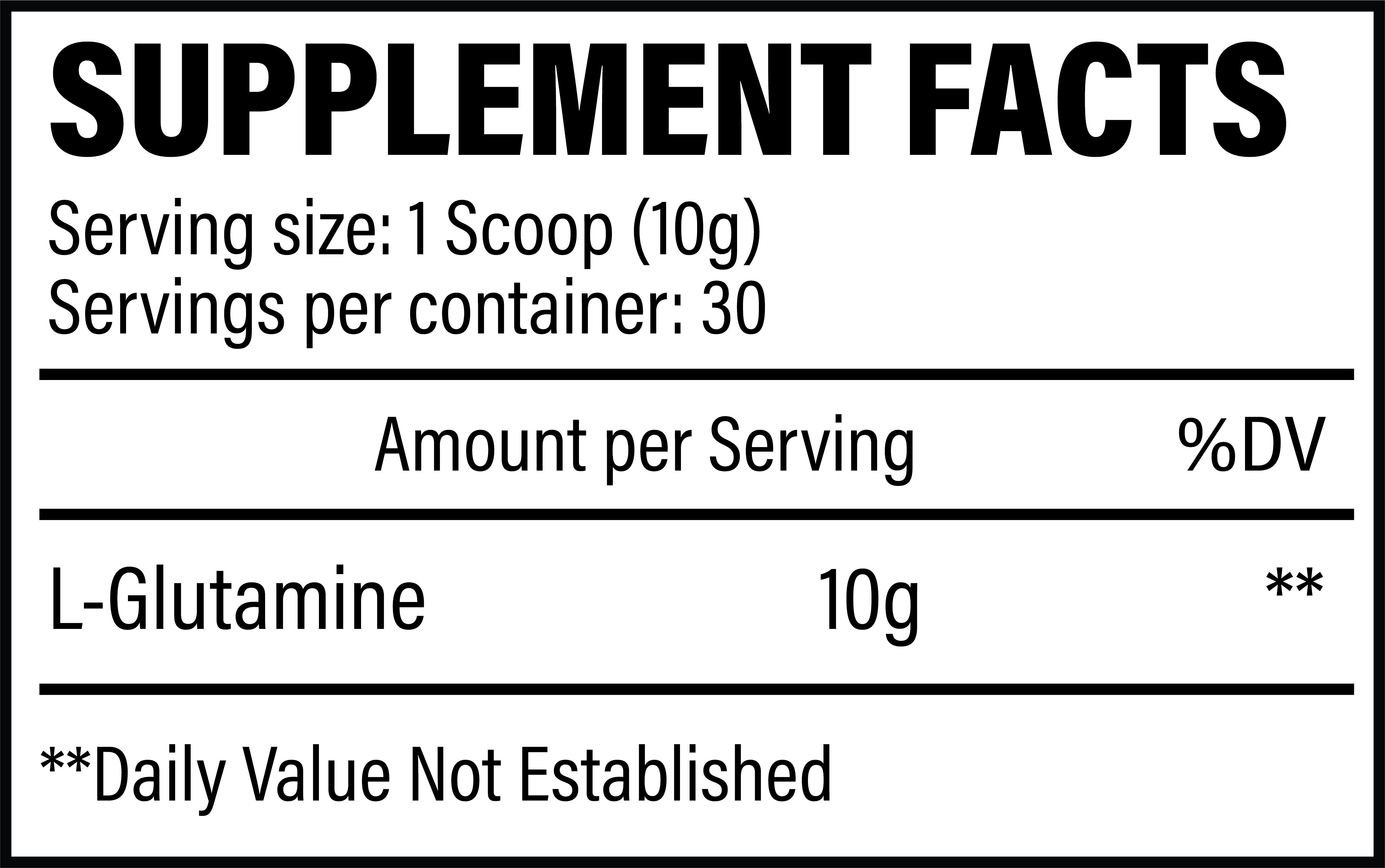

Revive MD Glutamine

In a 1996 research review with the auspicious title, "Glutamine," the authors stated, "There is also considerable evidence that glutamine can enhance the barrier function of the gut."[130] A closer look at the study teaches us that in times of illness,[131] animals' guts consume huge amounts of glutamine,[130,131] suggesting that it has some kind of direct anti-stress effect.

Glutamine is consumed excessively by stress and trauma

Revive MD Glutamine is here to bolster your gut health stack, which includes GI+, Fiber, Digest Aid, and Probiotic

In a 1991 study, seven hospitalized patients with serious trauma were hooked up to catheters and analyzed continuously during their recovery. Researchers found that although the rate at which the patients metabolized other amino acids was unaffected, their measured levels of glutamine dropped significantly, implying that glutamine was being metabolized more rapidly as a result of the trauma. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that the same patients had higher-than-normal levels of citrulline, which is a byproduct of glutamine metabolism.[131]

Glutamine deficiency and gut atrophy

Researchers have known for a long time that the human gut atrophies during long-term parenteral nutrition (where nutrition is provided in such a way as to bypass the digestive tract). Adding glutamine to parenteral nutrition significantly reduces the associated gut atrophy,[132] which should show us just what a powerful role glutamine plays in maintaining the gut.

Glutamine and the gut lining

The human gut doesn't just absorb nutrients. It's also semi-permeable, meaning that it's supposed to selectively allow nutrients to pass through while inhibiting the absorption of toxins and pathogens. In other words, the lining of the gut is a big part of the body's innate immune system.

The difference here is that Revive MD is using 10 gram scoops, which is double the norm. Go big for your gut!

In the research literature, glutamine is known as a substance that can enhance the gut's mucosal barrier,[133] thus optimizing its innate immune function.

When the mucosal lining begins to break down, the selective permeability of the gut becomes more and more indiscriminate. Eventually, a condition arises called leaky gut syndrome where undigested food particles seep out into places where they don't belong, which can cause chronic inflammation.

Glutamine consumption is recognized as the most important factor in healing leaky gut.[134,135] Many studies have shown that the nutrient is capable of reducing intestinal permeability for pro-inflammatory and pathogenic molecules.[136-141]

Gut mucosa and innate immunity

This is basically the reason why glutamine helps boost immune function: when gut tissue is strong and supplied with all the amino acids it needs to function optimally, the immune system is more likely to defeat invading pathogens. This is because high-glutamine diets are known to prevent some bacteria from passing through the mucosa.[142,143]

No surprise, then, that low levels of plasma glutamine are associated with reduced immunity and higher rates of infectious disease.[144]

Glutamine as an “immunonutrient”

Beyond strengthening the gut at the tissue-structural level, glutamine is also capable of serving as an energy source for certain cells in the digestive tract,[145] much like butyric acid, which we discussed above. Glutamine's ability to power the function of enterocytes and epithelial cells translates into improved immunity, especially in surgical and critically ill patients.[145]

According to a 2012 meta-analysis, glutamine's ability to heal and protect the human digestive tract means that it improves barrier function and morphology, decreases mucosa atrophy, prevents radiation-induced GI injury, reduces oxidative stress, boosts mucosal lymphocyte count, and lowers intestinal permeability and inflammation.[134]

Revive MD Glutamine – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

-

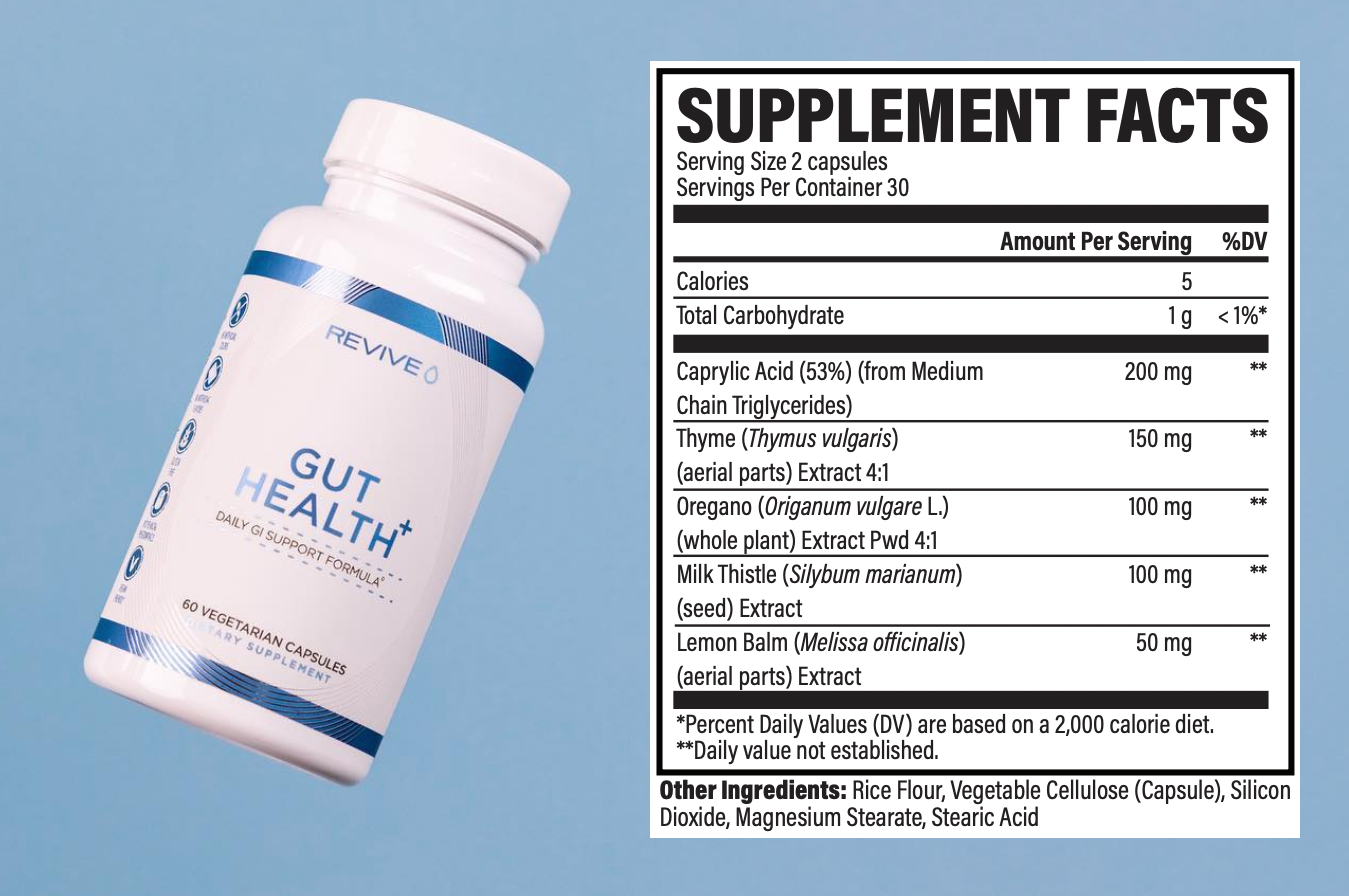

Revive MD Gut Health+

Added on Black Friday of 2022 (alongside a release of Betaine HCl for stomach re-acidification and Zinc Carnosine for ulcers), Gut Health+ has numerous antimicrobials inside to help limit harmful bacterial overgrowth. It's especially useful in combating candida.

Revive MD Gut Health+ – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Overall, Revive MD's probiotic is a different spin on a category that's been worn-out and perhaps not as effective as many would like it to be. We believe that a focus on probiotics without removal of the metabolic insult (generally ultra-processed foods) will be for nought, but when used alongside a cleaner diet, improvements anecdotally seem to be made more expeditiously.

Revive MD Probiotic – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Takeaway: The kitchen sink gut health stack

This six-product digestive health stack from Revive MD covers pretty much all the major digestive bases except for direct probiotic supplementation – although several of the ingredients in these products will indirectly improve the composition of your gut flora by various mechanisms.

Revive MD has an incredible, third-party tested product line, going well above and beyond supplements.

We understand that this is a lot to take in -- sometimes you can simply use more fiber and a bit of digestive support from Digest Aid. But other times, you're in a seriously nasty situation, and need to throw restorative ingredients at it. This is where GI+, Gut Health+, and Glutamine come into the picture.

Ultimately, we have to recognize that we didn't have such horrendous digestive problems a couple generations ago. Some people did, but nothing to this extent. Something has clearly changed, and that something is also changing you. It's time to fight back, but that means serious changes and cooking your own food.

So, on top of fighting for better gut health using the above supplement stack, we always recommend removing modern foods that your great grandmother wouldn't have seen in her childhood, and getting back to the pillars of ancestral eating - animal fats and organ meats included.

But to help repair the damage done, Revive MD and its team of professionals run under Dr. Domenic Iacovone and Matt Jansen have quite the stack here for you.

Revive MD – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)