MuscleTech is one of the supplement industry's innovator brands. It was MuscleTech, after all, that pioneered the use of paraxanthine – the "new and improved caffeine" – in their iQ Series of supplements that includes the EuphoriQ pre-workout and Burn iQ fat burner. Since then, plenty of other formulators have followed suit, and we're seeing paraxanthine show up all over the place. It's just one great illustration of MuscleTech's ability to set industry trends.

MuscleTech Creatine Chews have been launched in a delicious Citrus Burst flavor, bringing 1 gram of Creapure creatine monohydrate in every chewable tablet!

But pushing the boundaries isn't all that MuscleTech is good at – the company has solid entries in staple product categories as well.

Back in July, we covered MuscleTech's release of their Platinum 100% Creatine line, which uses only Creapure, the industry's most trusted brand of creatine monohydrate. With the Platinum 100% Creatine launch, we saw MuscleTech offering both pills and powder forms of the product, which of course tops off their famous Cell-Tech.

Well, now they're adding a new form of creatine to their product catalog.

MuscleTech Creatine Chews Debut in Lemon Lime Goodness

With MuscleTech Creatine Chews, the brand is now offering Creapure in chewable tablet form. Chews have taken off recently, because as supplement consumers get more informed and the complexity of their supplementation regimens grows, many end up taking tons of different powders, leading to what we call "powder fatigue".

Chewable supplements offer a super convenient, fun, and tasty alternative to the traditional powder-and-water mix – they're definitely more interesting than pills! And with the dextrose used as a carbohydrate source inside, there could even be a touch of post-workout synergy.

Let's get into these new creatine chews, but first, check the PricePlow news and deals:

MuscleTech Creatine Chews – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

MuscleTech Creatine Chews Nutrition Facts

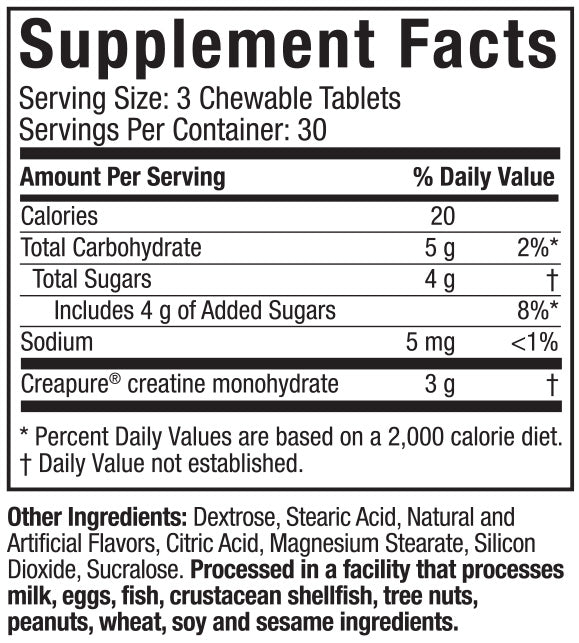

First, let's quickly state that each three-tablet serving has 3 grams of creatine monohydrate, so the math's simple - take one chewable tablet for each gram of creatine you want.

Next, the calories and carbohydrates in three tablets:

-

Calories: 20

-

Total Carbohydrates: 5 g

-

Total Sugars: 4 g

So we have 1.667 grams of carbs in each tablet next to 1 gram of creatine. You can probably guess (correctly) this is going to taste good.

MuscleTech Creatine Chews Ingredient: Creatine!

The main active ingredient is CreaPure creatine monohydrate, so let's do the deep dive on what it is and how it works.

Creatine dominates the supplement market today. Anyone who's serious about building muscle takes it or, at a minimum, has taken it before and eats plenty of creatine-heavy meat.

The most-well studied supplement ingredient ever

Decades since its introduction in the supplement industry, creatine has been subjected to a lot of additional scrutiny. A veritable mountain of evidence has concluded, overwhelmingly, that creatine is both effective and safe – for healthy adults. People with existing kidney disease will want to ask their doctor, but even that's up for debate nowadays.[1,2] As for healthy individuals, creatine supplements appear to be incredibly safe.[3-5]

What creatine does

Now that we've touched on the safety part, let's talk about creatine's effectiveness. What exactly does it do, and how? As it turns out, a comprehensive review of the research literature on creatine yields a laundry list of benefits that go far beyond just muscle building:

- Greater muscular power[6,7]

- Faster weight gain[7]

- Improved lean mass gain[7-11]

- Faster sprint speed[12-14]

- Better cellular hydration[15]

- Greater energy levels[16-19]

- Stronger feelings of overall well-being[19-21]

- Increased cognitive performance[22,23]

- Higher testosterone levels[24-28]

- Denser bones[10]

How creatine works

We think you'll agree that the foregoing list is very impressive. Whenever we see that a single supplement can have such significant benefits in so many domains of health and performance, we start to look for a fundamental mechanism of action – that is, we begin to suspect that the supplement in question coherently affects metabolic function at a deep level, and in a general way.

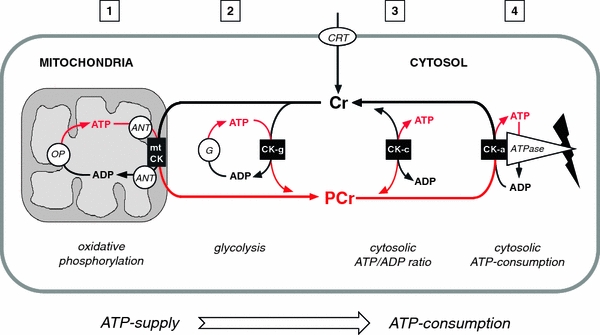

In creatine's case, the profound mechanism is adenosine triphosphate (ATP) upregulation.

Regular readers of The PricePlow Blog don't need to be told that ATP is critically important for health and performance. It's your body's energy currency, the form of energy that your cells actually burn to perform their various metabolic functions. If you think of your body as a car, then ATP would be the gasoline – without it, the car isn't going anywhere. In fact, it isn't even starting.

A phosphate donor for our conversion from ADP to ATP

ATP's most immediate precursor is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a molecule called adenosine di-phosphate (ADP), which is distinguished from adenosine tri-phosphate by having two phosphate groups instead of three. In our car analogy, you could think of ADP as crude oil, which your body "refines" into ATP.

A study published in 2011 does a fantastic job showing creatine's role in the production of ATP in the mitochondria.[29]

In order for your body to convert ADP into ATP, those extra phosphate have to come from somewhere – and that's where creatine comes into play. It turns out that creatine is a phosphate donor, meaning it contains phosphate groups that your cells can co-opt and use for the ADP-to-ATP conversion process.[30-33]

Every cell in your body can benefit from ATP optimization

While the most common use case is, again, to enhance athletic performance and recovery, the benefits are more general than that. After all, all your body's cells need ATP, including neurons.

So can creatine saturation benefit the brain? According to a 2018 meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the answer is yes – creatine supplements are capable of increasing performance on short-term memory, intelligence, and reasoning tests.[34] Other studies have found that creatine supplements can be neuroprotective, helping prevent or limit the severity of damage to brain tissue after traumatic brain injury (TBI).[35]

The argument for supplementation

Given how important ATP synthesis is for health and performance, and how important creatine is for ATP synthesis, you've probably guessed by now that the human body can synthesize its own creatine, endogenously. If we can make our own creatine, why take it as a supplement?

Creatine metabolically-expensive to generate in your body

The answer is that creatine synthesis is a metabolically expensive process. We actually found one peer-reviewed study that refers to this reality as the metabolic burden of creatine synthesis,[36] and argues that this process consumes phosphate groups – and other nutritional precursors – that are needed for other important metabolic processes as well.

So, there are two potential issues with relying on your body's creatine synthesis pathway:

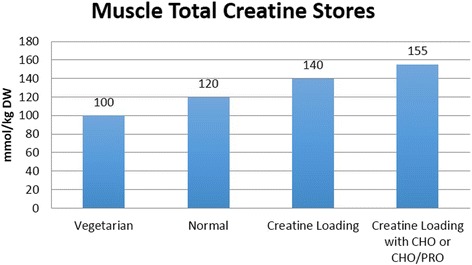

The amount of creatine you may need depends on your diet and activity. Research shows that vegans/vegetarians have far less in their muscle tissue.[5]

- You may end up not producing enough creatine to cover all your cells' requirements, if the required precursors are being used up in other metabolic pathways. And conversely,

- If your body prioritizes creatine, then those other processes might be compromised instead.

This was illustrated in an animal study where physical exercise was found to increase the blood homocysteine concentrations of rats. This happened because exercise sped up the rats' metabolisms, meaning that the cofactors for homocysteine metabolism were consumed at an elevated rate. But creatine supplementation reversed this effect, bringing homocysteine back under control.[37]

A critical, conditionally essential nutrient

On this line of thinking, researchers recently suggested that creatine is even useful for patients with chronic kidney disease, since it lowers the amount of endogenous production the body would have to make itself, attenuating unopposed losses of creatine.[1,2]

This is proposed in a very well-written review titled "Creatine is a Conditionally Essential Nutrient in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Hypothesis and Narrative Literature Review",[2] and is worth reading since it goes against the grain of everything that's been pushed by mainstream media.

CreaPure, the industry's most trusted form

Regarding Creapure, MuscleTech's creatine brand of choice, there are two important facts to consider.

First of all, Creapure is creatine monohydrate – a creatine molecule bound to a single water molecule.[39] This is the best form of creatine to take as a supplement, for the simple reason that it's the most studied form by far, in terms of both safety and efficacy.[4,38]

Second, Creapure as a brand has been around forever. It's one of the OG creatine standardizations, and has a long and totally untarnished reputation for high product purity. When MuscleTech goes in on something, they go big and international, and they've decided to have one less headache by going with the tried-and-true brand that's known around the world.

How much creatine do we need?

The average man loses roughly 1.6% to 1.7% of his body's total creatine reserves every day.[40,41] For women, the number is slightly smaller, but in the same ballpark.[42]

We all love that Cell-Tech, but sometimes you want some solo creatine, or you want to start loading on top of it. MuscleTech now has Platinum 100% Creatine in capsules and powders, both with Creapure creatine monohydrate

This translates to a loss of about 2 grams of creatine per day.[42] Taking this number as an obvious baseline for creatine intake, we can see that you should consume at least 2 grams of creatine, in order to replace what you lose if nothing else.

However, keep in mind that we're talking about an average. The amount of creatine needed varies significantly from individual to individual, with higher body mass and physical activity levels translating to higher creatine requirements. If you're the typical male athlete, powerlifter or bodybuilder, you probably need more like 3 grams of creatine per day, since strenuous exercise has been shown to increase the amount of creatine lost daily by as much as 50%.[43]

What's great about MuscleTech Creatine Chews is that you can take whatever amount you like, whether it's 2 or more tablets... so long as you don't eat, say, more than 20 in a day! And on that note, let's talk about the higher doses used in loading:

Is the loading phase necessary?

Standard practice for creatine supplementation is to start with a several-weeks-long loading phase, in which you take roughly 20 grams per day for about a week. The idea is that, because creatine's effectiveness depends on the extent to which it has saturated your tissues, front-loading it can help you achieve creatine saturation faster.

MuscleTech EuphoriQ is the smarter pre-workout supplement - an enfinity-powered nootropic pre-workout supplement that harnesses paraxanthine instead of caffeine!

Once the loading phase is complete, the creatine dose is typically reduced to 5 grams/day for maintenance. While this definitely sounds like broscience, peer-reviewed research attests to the effectiveness of a loading phase.[44]

However, if you want to keep things super simple, you can just take 5 grams a day from the beginning, and your stores will accumulate over time. This dose is sufficient to achieve creatine saturation in the vast majority of people.

It also depends on another factor: your diet.

Creatine from food?

We also get creatine from food. It occurs exclusively in animal products, particularly meat.

When it comes to the American diet, beef is probably the most widely-consumed source of creatine, and comes in at about 2 to 2.5 grams of creatine per pound.[45,46] Chicken contains slightly less, with only 1.5 grams per pound.[47]

Herring has the highest creatine content of any food – it clocks in at 3 to 4.5 grams of creatine per pound![48]

While you could get all the creatine you need from eating 1 to 1.5 pounds of herring daily, let's be honest, most individuals are not doing that. And sadly, that much fish comes with its own set of problems these days, so it's generally not recommended. As such, the average American man gets only 1 gram of dietary creatine each day, and the average American woman only 0.70 grams.[49]

In other words, the average American is not consuming enough creatine-based foods to cover ideal daily requirements. This means reliance on the endogenous creatine synthesis pathway, which, as we discussed earlier, is metabolically inefficient.

Thus, it stands to reason that most people can benefit from taking a creatine supplement. Only question is what form factor -- and now MuscleTech gives you options in Creatine Chews alongside their Cell-Tech series (Cell-Tech, Cell-Tech Elite, and Cell-Tech Creactor) and standalone Platinum 100% Creatine line.

The Carbohydrate Source: Dextrose!

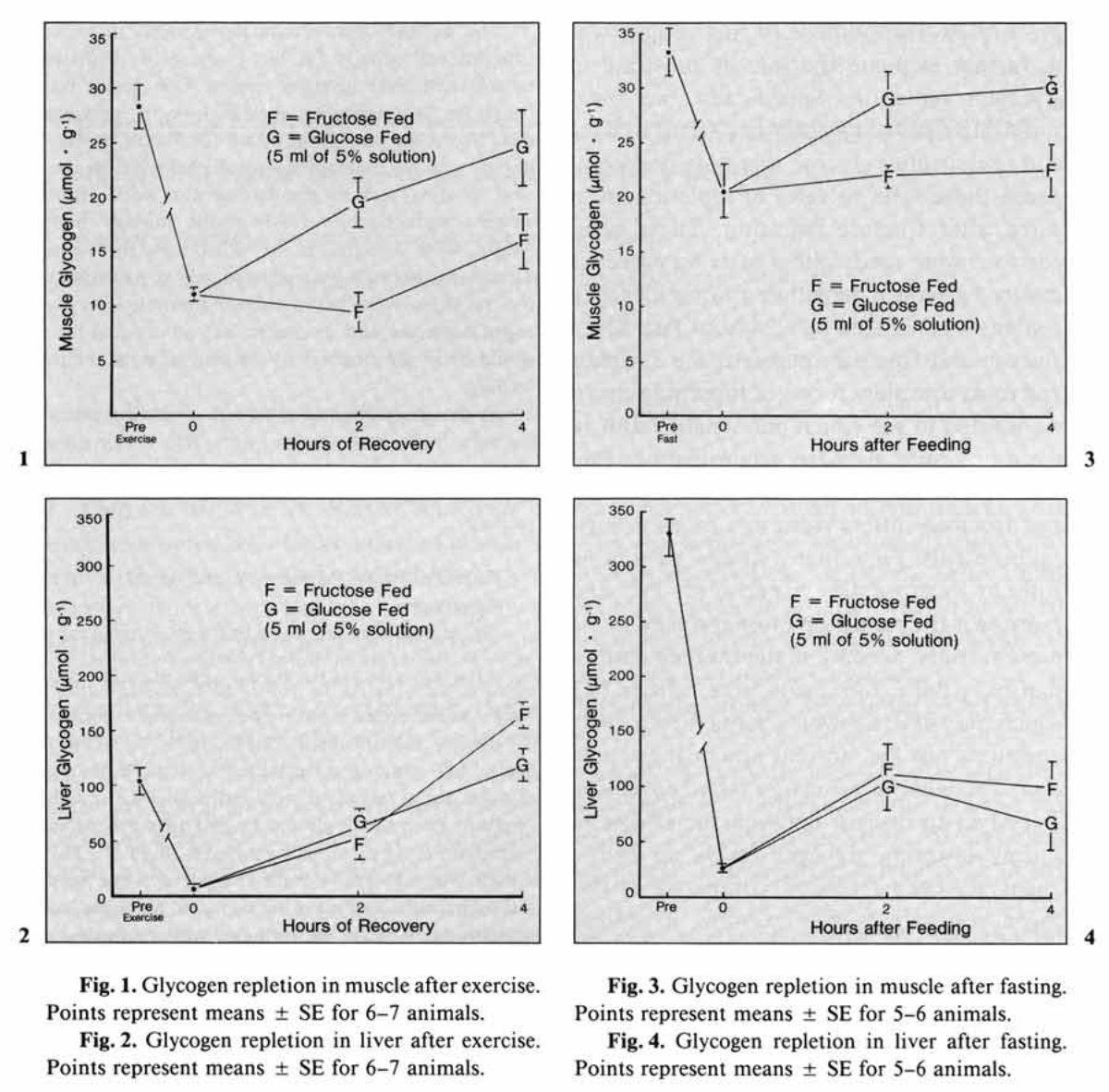

Fructose reloads liver glycogen, but dextrose/glucose reload muscle glycogen.[50] So why waste time with fructose? Cut to the chase with straight up dextrose!

It's worth noting that dextrose is the single carbohydrate source, aside from perhaps a bit more that could be in the flavor system. As oppoosed to table sugar (sucrose), which is half glucose, half fructose, dextrose is pure glucose! Dextrose actually stands for "d-glucose". It's simple, it's what the body already uses, and research has even shown that muscle glycogen synthesis rates are faster and better with oral dextrose than fructose![50-52] (These studies show that fructose is better at loading the liver, not what we need or want post-workout.) That's also been shown in intravenous treatment,[53] but we stick to oral data when we can.

Reason being, fructose absorbs more slowly in the intestine,[54,55] and the liver ends up having to convert fructose to glucose anyway,[55-57] and that's a slow process.[58] MuscleTech skips that and just go with the source that ends up in the muscle -- dextrose!

Flavors Available

MuscleTech first launched Creatine Chews in a Citrus Burst flavor that's an excellent blend of sweetness with lemon and lime. Over time, we're hoping we'll see even more in our list:

Barely worth noting, but there's also a negligible 5 milligrams of sodium in the Citrus Burst flavor, which is about 0.2% of the recommended daily value - it's likely in the flavor system, since salt isn't listed anywhere in the label.

A Delicious Way to Get Creatine and a Few Post-Workout Carbs

Put simply, creatine works. It's a supplement that we would recommend to almost anybody – assuming kidney disease or other health issues don't disqualify one from using it (if you're not sure, ask your doctor).

Chewables are a great addition to the MuscleTech creatine product lineup, and if MuscleTech's track record is any indication, the flavors are going to be super delicious.

MuscleTech Creatine Chews – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)