MuscleTech is a company with great bona fides in product innovation. For example, they were first to bring paraxanthine to the market in their EuphoriQ Pre-Workout, delivering a kind of caffeine 2.0 that's made a huge impact with consumers thanks to its comparatively low side effect profile.

But it's not always about new ingredients - classic, tried-and-true ingredients are classics for a reason. Today, we're talking about MuscleTech's re-entry into an essential industry category: supplemental creatine.

We all love that Cell-Tech, but sometimes you want some solo creatine, or you want to start loading on top of it. MuscleTech now has Platinum 100% Creatine in capsules and powders, both with Creapure creatine monohydrate

MuscleTech: No Stranger to Creatine

Most readers are familiar with MuscleTech's creatine formulas under the legendary Cell-Tech namesake. They currently have three versions available in the very affordable lineup:

- Cell-Tech - 5 gram creatine monohydrate with added amino acids and 38 grams of carbs!

- Cell-Tech Elite - 5 gram creatine blend with 6g EAAs and Peak ATP

- Cell-Tech Creactor - A 5 gram blend of creatine HCl and free-acid creatine (creatine anhydrous).

If you haven't looked at Cell-Tech recently, then look again - these formulas are wildly underrated. But sometimes, you want just solo creatine monohydrate to add to your EuphoriQ pre-workout, or any other drink for that matter. So MuscleTech has delivered:

MuscleTech Platinum 100% Creatine – Pills or Powder?

In the summer of 2023, MuscleTech launched two new creatine products... but they're not under the Cell-Tech name. It's MuscleTech Platinum 100% Creatine, which come in both pill and powder options and feature 100% creatine monohydrate.

You might think there's not much to say about creatine because, after all, creatine is creatine – or is it? We appreciate the fact that MuscleTech has opted to use Creapure, a brand of creatine with a longstanding reputation for exceptional purity and international compliance - exactly what a major brand like MuscleTech needs.

The innovators of paraxanthine-based supplements with EuphoriQ, MuscleTech also brings the tried-and-true basics like Creapure creatine monohydrate!

Another thing we like is that MuscleTech gives you a choice between pill form or powder form. For whatever reason, this isn't something we often see from other brands, but some consumers definitely have strong preferences one way or the other, so it's great to see MuscleTech offering this option.

Let's talk about the science behind creatine and how it works. Creatine is a big subject, so we could probably all use a refresher from time to time.

MuscleTech Platinum 100% Creatine – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

This area is reserved for Team PricePlow's upcoming videos.

Subscribe to our channel and sign up for notifications so you catch it when it goes live!

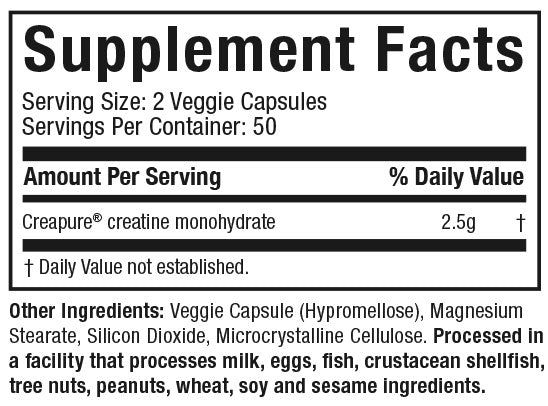

First, let's talk about the two serving sizes:

- If you get the powder, each scoop has 5 grams

- If you get the capsules, each capsule has 1.25 grams

So if you're wondering, the answer is yes, these are very large capsules! Now let's get into the creatine refresher and talk about Creapure specifically:

A primer on creatine and creatine monohydrate

Creatine is naturally-occurring, non-protein amino acid found prevalently in meat,[1-3] fish,[4,5] and interestingly, cranberries.[6,7] It's mostly stored in skeletal muscle and is used to provide critical phosphate groups to our body's primary energy source, ATP (adenosine triphosphate).[8] Without enough stored creatine (due to poor diet, overexertion, lack of supplementation, and/or impaired ability to generate it), mental and physical performance are both significantly diminished.[9]

Since the 1990s, a ton of research has been conducted on the ingredient, which overwhelmingly points to creatine being effective and safe.[10] It's always suggested to talk to a doctor before beginning any new diet or supplement program, but for vast majority of healthy adolescents and adults, creatine supplementation is extremely safe.[10-12]

We're now at the point where modern creatine studies have over 250 citations of other creatine studies,[10,13] and there are meta-analyses covering specific sports, activities, and goals (many cited below). It's, at this point, without dispute: creatine is the king ingredient of the dietary supplement world.

Creatine's benefits

It's probably the case that most readers here have used creatine at some point. Far fewer of us, however, understand the true extent of creatine's benefits for human health, which can go way beyond helping us exercise and build muscle.

Creatine supplementation has been shown to:

- Increase muscle power[14,15]

- Accelerate lean mass gain[15-19]

- Increase sprint speed[20-22]

- Improve cellular hydration[23]

- Increase felt energy[24-27]

- Accelerate weight gain[15]

- Improve sense of overall well-being[28-30]

- Support optimal cognition[31,32]

- Increase testosterone production[33-37]

- Increase bone density[18]

The last four points on this list should be of particular interest to anyone who doesn't eat a lot of meat, as meat is, hands-down, the best dietary source of creatine.[1-3] That means, vegans and vegetarians, this article is especially for you!

Creatine's mechanism of action

Impressive though the foregoing list may be, it's actually not even a complete list of creatine's benefits. It's truly impressive that one supplement can confer such diverse and far-reaching benefits on human health.

When we see a "silver bullet" supplement like this, we might expect to find that it improves a fundamental metabolic process – and that's exactly what creatine does.

ATP: The "gasoline" of your body

As it turns out, creatine can help increase adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, which is extraordinarily important. ATP is the energy currency of your entire body, used by your cells to power every single metabolic task they undertake. To use an analogy, if your body were a car, ATP would be the gas – no gas, and your car can't drive anywhere. In fact, it won't even turn on.

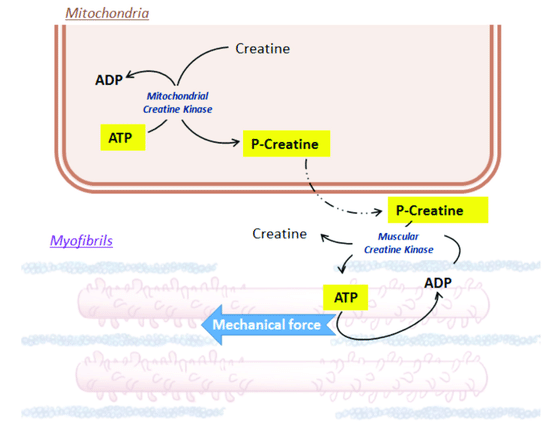

The direct precursor to ATP is adenosine di-phosphate (ADP), a molecule containing two phosphate groups instead of ATP's three. In our analogy, ADP is kind of like crude oil, the thing your body "refines" into ATP.

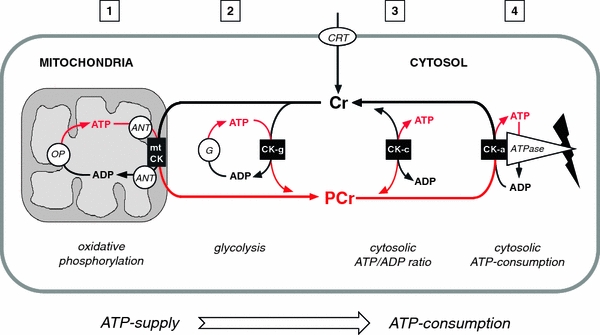

Where the analogy breaks down is in the fact that while oil refining is a "purification" process, converting ADP to ATP is an additive one. To make ATP, your body needs additional phosphate groups, and that's where creatine comes in. Creatine acts as a phosphate donor, delivering needed phosphate groups to your cells' mitochondria, which use the phosphates to turn ADP into ATP.[8,38-40]

A study published in 2011 does a fantastic job showing creatine's role in the production of ATP in the mitochondria.[41]

These are the high-energy bonds that your body uses to power itself. And creatine holds what's needed to build more of them. Without it, everything gets sluggish.

All your body's cells can benefit from ATP upregulation – including neurons

Although creatine is usually taken by athletes and bodybuilders for its impressive physique and performance benefits, there's a significant cognitive dimension to ATP's potential advantages.

This is because your neurons need ATP just as much as other cells. A 2018 meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials found that creatine supplementation can improve short-term memory, intelligence, and reasoning.[42] Other research indicates that supplemental creatine may even be neuroprotective, and useful for mitigating damage to neural tissue following traumatic brain injury.[43]

Why supplement with creatine?

You may have inferred from this discussion that the human body can make creatine on its own. So, why should we take a creatine supplement?

The answer is that creatine production is metabolically expensive. One study, speaking of the metabolic burden of creatine synthesis,[44] points out that creatine production consumes many dietary precursors that are important for other processes.

Thus, there are two potential problems with relying on your body's endogenous creatine synthesis: First, you may end up producing suboptimal amounts, thanks to precursor shortage (we haven't seen research on the prevalence of this specific problem, but it seems to be an issue in vegans), genetically impaired abilities to generate it effectively,[9] or the body's prioritization of creatine synthesis may ultimately compromise other important metabolic processes.

Ultimately, unless you're eating over two pounds of meat per day, supplementing creatine will make life easier on your body, improving basically everything requiring ATP.

Why Creapure creatine monohydrate?

When it comes to MuscleTech's chosen creatine, there are two important aspects to discuss.

The first is the chemical form of the creatine, creatine monohydrate, a creatine molecule bound to a single water molecule.[45] The reason to prefer creatine monohydrate is simple: it's the most studied by far, and consistently found to be safe and effective.[12] Monohydrate is what you should take if you want the most clinically-studied form.

Second, we like seeing the Creapure brand being used. Creapure is one of the OG creatine standardizations – bodybuilding and supplement veterans will definitely recognize it, thanks to its reputation for exceptional purity.

In 2022, Creapure sponsored a study comparing creatine monohydrate to every known form of creatine on the market.[13] They wrote the following in their conclusion (CrM = Creatine Monohydrate):

"CrM remains the only source of creatine that has substantial evidence of bioavailability, efficacy and safety and is considered GRAS by the U.S. FDA, is approved for use with accompanying health claims in the EU, has been extensively reviewed and approved by Health Canada, and is approved to be sold in major global markets. The bioavailability, efficacy, safety, and regulatory status of other purported sources of creatine are less clear, with only a few having some data supporting efficacy compared to placebo (see Table 7). However, there is no evidence that other "forms" of creatine are more bioavailable, effective, or safer forms of creatine compared to CrM."[13]

Human creatine requirements

So how much creatine do we need? Let's run the numbers.

The average man loses about 1.6% to 1.7% of his total creatine reserves every day.[46,47] For women, it's slightly less.[48]

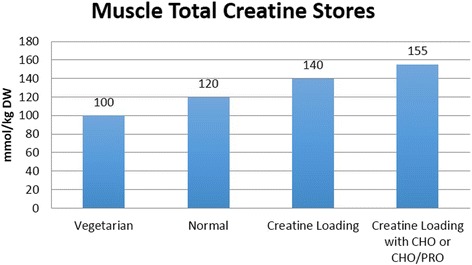

The amount of creatine you may need depends on your diet and activity. Research shows that vegans/vegetarians have far less in their muscle tissue.[10]

In absolute terms, this means that the average person is losing approximately 2 grams of creatine per day.[48] We can take this number as an easy baseline for estimating creatine intake requirements. At a minimum, you should replace what you lose, meaning you need to consume at least 2 grams of creatine from food and supplements daily.

There is significant individual variation though. The amount of creatine you need increases the larger and more active you are. So if you're a big weightlifting male, your creatine need is probably closer to 3 grams per day, since demanding workouts can increase creatine loss by as much as 50%.[49]

Some numbers on the dietary sources of creatine

Beef is probably the most commonly consumed creatine-rich food in the standard American diet – it clocks in at about 2 to 2.5 grams of creatine per pound.[1,50] Chicken contains slightly less – about 1.5 grams per pound.[2] Most fish have lower amounts, so vegetarians still greatly benefit from supplementation. We joke about it being in cranberries, since it's just scant amounts.[6,7]

So, for the average American to get enough creatine from food, they need about 2 pounds of beef or 3 pounds of chicken per day.

Let's be real, most readers are probably not eating this much meat on a regular basis. It isn't terribly surprising, then, that the average American man gets only 1 gram of creatine from his food every day. Women get even less – about 0.70 grams.[51]

In other words, if your diet is anything close to the American average, you almost certainly stand to benefit from creatine supplementation.

How to take creatine

The standard technique for creatine supplementation is to begin with a loading phase in which you take 20 grams per day for about a week. Although this might sound like bro science, there's actually good evidentiary basis for doing this.[52]

If that's too complicated, though, you can just take the standard 5 gram dose of creatine instead. It will eventually reach creatine saturation.

Should you take it pre- or post-workout? It doesn't seem to matter much - just get it in every day, even rest days. Test it alongside MuscleTech EuphoriQ, though -- some anecdotally feel "fuller" with bigger pumps when adding creatine and more water.

Conclusion: There's More Than Cell-Tech at MuscleTech!

MuscleTech EuphoriQ is the smarter pre-workout supplement - an enfinity-powered nootropic pre-workout supplement that harnesses paraxanthine instead of caffeine!

We love Cell-Tech, and as we said in the intro, if you haven't looked at the recent formulas (especially Cell-Tech Elite), it's time to take another look.

But sometimes, you just have to keep it simple. You've already got EuphoriQ or Burn iQ and just need that one last ingredient -- and it's the king of them all: creatine!

Not much else to say on the topic – creatine monohydrate just works. And unless you're eating literal pounds of meat every day, supplementing more will greatly ease the burden on your body. Again, we appreciate MuscleTech offering the choice between pills or powder, and we definitely like to see Creapure making an appearance.

And if you want to impress your friends, show them those 1.25 gram capsules - these beasts don't mess around!

MuscleTech Platinum 100% Creatine – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)