Important Update: This lawsuit has been settled! Subscribe to our YouTube channel and sign up for our Protein news alerts to get notified when it's public - Lenny and Larry customers may have some cash coming back to them!

Are Lenny and Larry's Complete Cookies a bit less complete than consumers thought? We don't know, because lab tests haven't been released and these are only allegations.

On February 28th, 2017, two Illinois citizens filed a class action lawsuit against Lenny & Larry's Inc, with allegations of unfair and deceptive practices regarding the sales and marketing of Lenny & Larry's Complete Cookies.

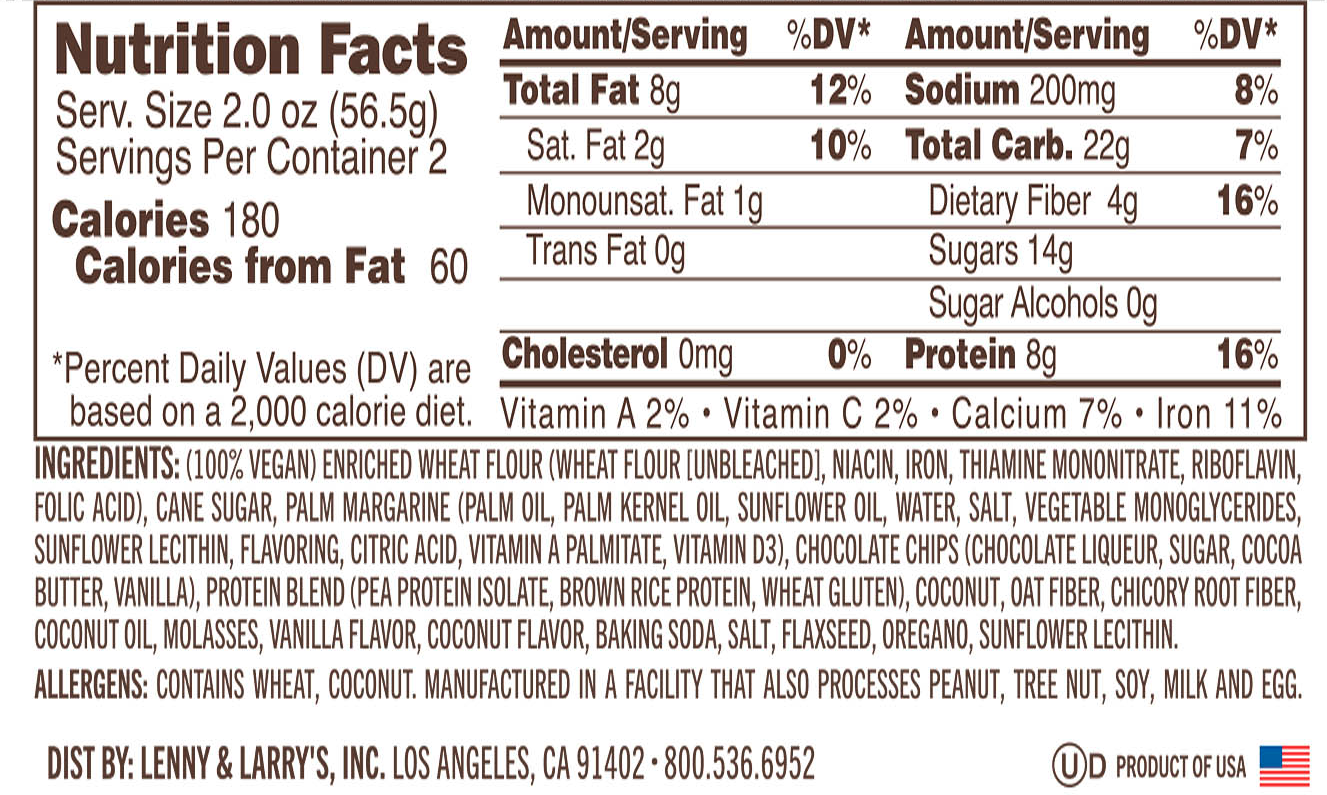

The plaintiffs in this suit accuse the famous protein cookie company of false and misleading claims with regards to the Complete Cookie's protein content - specifically "the percent of daily value, sources and quality of the protein content, and the actual amount of protein in the Product."

We've been asked numerous times our thoughts on this case, and the initial answer is that we are still in information-gathering mode.

With that said, you can download the class action complaint below, and then we'll discuss what we know and why this case is massively important:

What we know (and don't know) about the Lenny & Larry's Lawsuit

-

The lawyers will not release their lab tests.

We immediately contacted the legal team for the plaintiffs, requesting the lab tests, and were denied access to them.

Without actual lab tests, there is little actionable information to go on. This could be serious... but it could also be a shakedown attempt or a "legal test pilot" for the ongoing Body Fortress case (explained in detail below).

We don't know what flavors they've tested, what sizes they've tested, or what batch they're from. We also have no idea where they bought them from and how they can prove chain of custody and how they avoided counterfeits. There are simply too many unknowns.

-

Lenny & Larry's recently had a recall

On December 12, 2016, Lenny & Larry's issued an official recall notice through the FDA due to "the possible presence of undeclared milk in the dark chocolate chips" in certain lots of the Chocolate Chip and Coconut Chocolate Chip flavors.

It's possible that this is what began the legal investigation into the Cookies and their QA processes, but that's just speculation.

-

Lenny & Larry's has responded on Twitter (3/10/2017)

We're awaiting comment from Lenny & Larry's. Update: Lenny and Larry's has responded on Twitter, shown below.Lenny & Larry's response Tweet

@PricePlow Anyone can file a lawsuit, and this person has sued before only to have the Court toss her claim. This is no different.

— Lenny & Larry's (@lennylarrys_s) March 10, 2017

In case your connection blocks Twitter, they said,

Anyone can file a lawsuit, and this person has sued before only to have the Court toss her claim. This is no different.

-- Lenny & Larry's on Twitter

We've updated this post to include information on that case in the next section.

One important question we still wish to understand is how many manufacturing co-packers produce these cookies. If the allegations are true and there is an issue, is it systemic, or is it only certain lots or flavors, similar to the recall notice above?

-

One of the plaintiffs also attempted to sue KIND Bars... and her case was dismissed

Thanks to the response from Lenny & Larry's on Twitter, it turns out that one of the plaintiffs, Rochelle Ibarrola, has previously sued Kind LLC (creator of KIND Bars). That case was summarily dismissed as "the plaintiff could not sufficiently define the allegations of injury and deceit and could not establish how Kind LLC’s alleged misrepresentation of evaporated cane juice harmed the plaintiff and other Class Members".[1]

Why the Lenny & Larry's Lawsuit is a Big Deal

What's interesting about this case is that for the first time in the sports nutrition industry, the lawsuit is using PDCAAS, or Protein Digestibility Amino Acid Corrected Score, as a way of determining protein quality.

Bullet point 22 in the lawsuit explains PDCAAS very well:

The PDCAAS method does not simply calculate protein content by nitrogen analysis, but instead requires the manufacturer to determine the amount of essential amino acids contained within a product. This testing method ensures that consumers are being informed about the “quality” of the protein contained a product. PDCAAS measures protein quality based on human essential amino acid requirements and our ability to digest it.

The test protein is compared to a standard amino acid profile and is given a score from 0-1.0, with a score of 1.0 indicating maximum amino acid digestibility. Common protein supplements (whey, casein, and soy) all receive 1.0 scores. Meat and soybeans (0.9), vegetables and other legumes (0.7), and whole wheat and peanuts (0.25-0.55) all provide diminished protein digestibility.

The PDCAAS is currently considered the most reliable score of protein quality for human nutrition.*

*Interestingly, the plaintiff's lawyers cite a Labdoor article for the last statement in bullet point 22, which is odd due to Labdoor not being a government-sanctioned source, and Labdoor's protein verification methods have been called into serious question. When it comes to protein testing, we love Labdoor's goals, but not their stated methods nor grading criteria.

But let's not digress from the most important part of this case:

Learning from the Body Fortress Case

Regular readers may recall that PDCAAS came up in the November 2016 updates to the Body Fortress Lawsuit. Our guess here is that this class action complaint's text is based upon what they learned from the Judge's responses, where he denied some of Body Fortress's motions to dismiss the case.

There is a lot riding on this. If the case is upheld using PDCAAS scores, it may upend the entire food industry, and open everything in your fridge to class action tort, so you can bet that there are many eyes on this. More on that later, but first let's dig into where PDCAAS came from:

Is PDCAAS law?

PDCAAS Protein savior, or judge who unconstitutionally "legislates from the bench"? To be determined....

To demonstrate, in the Body Fortress case, Judge Manish Shah stated the understanding that “The regulations permit manufacturers to calculate the total amount of protein by multiplying the product’s nitrogen content by a factor of 6.25. See 21 C.F.R. § 101.9(c)(7)”...

-- but --

...he also cited that "the product must contain a statement of protein content as a percentage of the Daily Reference Value calculated using the “corrected amount of protein”—an amount that is not calculated by simply multiplying the amount of nitrogen by 6.25, but by taking into account the “protein quality value,” or “protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score.” See 21 C.F.R. § 101.9(c)(7)(ii)."

Digging deeper, 21 C.F.R. § 101.9(c)(7)(ii) references a book titled “Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Protein Quality Evaluation” that has finally been found here on apps.who.int but we've also made a backup here. Thanks to AC Slater (@TheStroBro on Twitter) for finding this document!

Our Body Fortress Lawsuit article's updates show a few of the important provisions of that FAO/WHO report as well.

Who defines protein, and why is it still so undefined?

The bigger question is whether or not PDCAAS is the "officially-recognized" way of testing protein - especially when not all sourcers have PDCAAS scores. The Obama-nominated Shah has been criticized by some industry insiders as legislating from the bench in this case. Is it his job to create case law that defines protein, or is it the FDA's on behalf of Congress?

This was predicted by our sources

Back in November, we even speculated that "every vegan protein (rice, pea, etc) with a PDCAAS (or DIAAS) score of less than one (like 99% of them) are not labeled right & subject to class action tort cases" - and here we are, with a vegan protein cookie under fire!!

This is exactly what Bruce Kneller predicted when we discussed this case.

What's the point?

The point is, these lawyers are getting smarter, but the plaintiffs' legal team may possibly be getting ahead of themselves if the protein content is clean per nitrogen and amino panel testing, but not 100% perfect per PDCAAS. This is why we need lab tests.

Without lab data, which the lawyers have refused to provide, we really can't say if this is that bad, or if they're merely testing the PDCAAS judgment from the Body Fortress case.

Either way, you better believe that the entire food industry is watching. This now goes beyond sports nutrition and protein powders.

Test it yourself?

This isn't to stop you from getting a lab test. For starters, the easiest thing you can do is to get a nitrogen-based protein test. If that comes in low, then you know there's a problem.

However, as we've seen with amino acid spiking, a successful nitrogen test (based upon the Kjeldahl method) doesn't necessarily mean the product is fairly labeled. A more thorough amino acid panel would be next - but that would cost around $2000!

Either way, nitrogen tests are the first low-cost line of defense for you to consider if you're really interested in this kind of thing.

Another industry-defining popcorn moment

All things told, there's a lot riding on this case -- that much we know -- but we don't know enough to make any good conclusions.

So stay tuned.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)