A new study shows that natural pomegranate juice greatly enhances performance and recovery, while also reducing markers of muscle damage (soreness).

There's no better feeling than the sense of accomplishment, brute strength, and machismo after a grueling workout where you simply left everything in the gym, no reps saved, no sets half-assed. The immediate sense of gratification is like nothing else. However....

Come a day or two later you're left with crippling soreness from pushing yourself to limits rarely experienced and you'd kick yourself for doing it, yet your legs are too sore to even lift that high. You've tried epsom salt baths, LCLT, and other common "recovery aids" but no luck. So you're left to just pop some NSAIDs to get through the pain (but that's never the ideal fix).

However, a recent study seems to have unearthed a rather powerful and all-natural supreme recovery agent -- natural pomegranate juice.

The Study

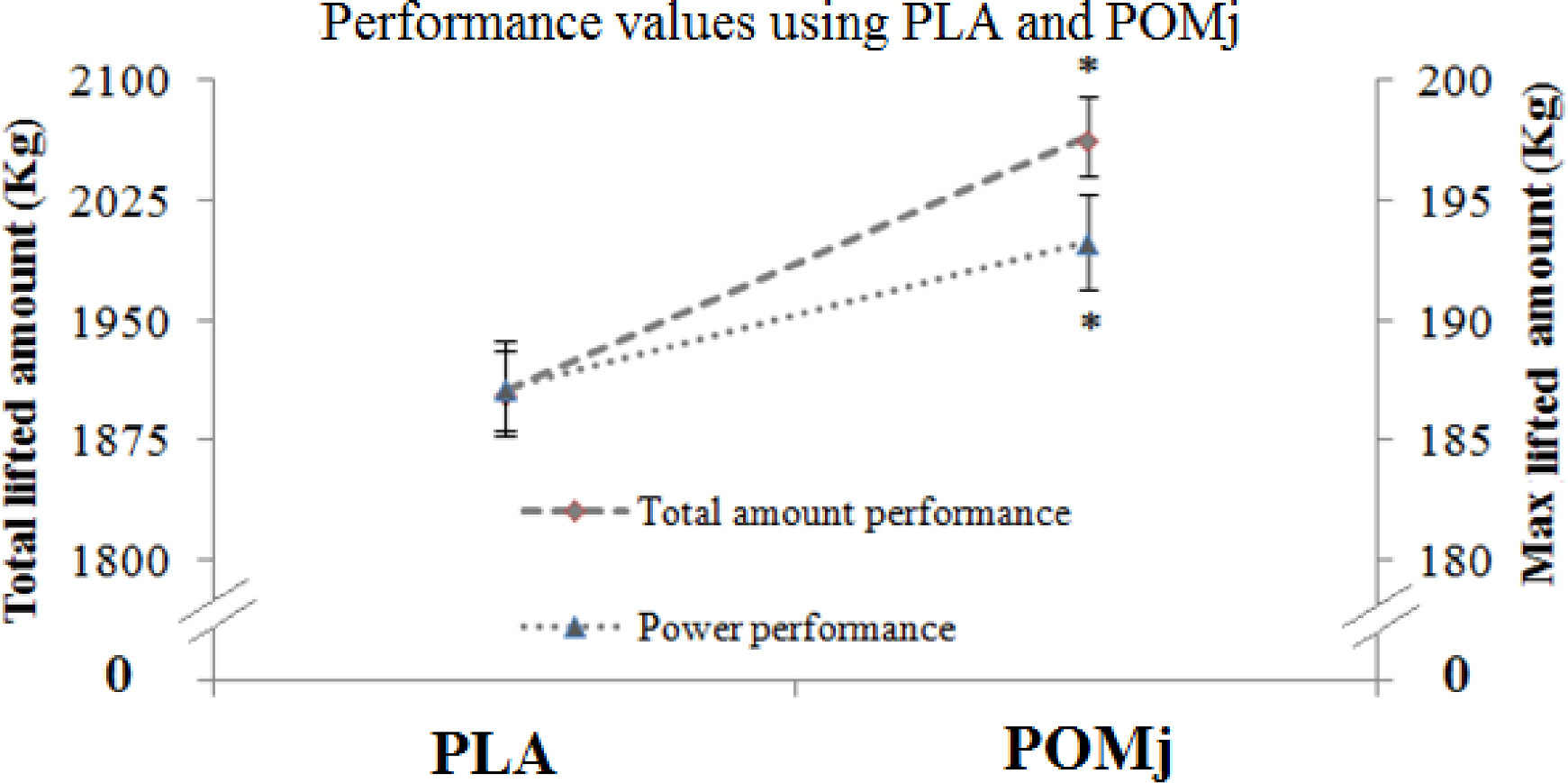

Fig 2. Calculated performances of placebo vs. pomegranate juice.

Note the significant differences between PLA and POMj conditions.[1]

A coalition of researchers from Sfax University (Sfax, Tunisia) and the Institute of Sports Science sought to investigate the effect of natural Pomegranate juice supplementation on athletic performance, as well as both acute and delayed responses of muscle soreness and biomarkers of muscle damage following weight training.[1]

Previous studies have been conducted on pomegranate juice and its effects on stress markers[2,3]; however in regards to its effects on recovery from exercise (one of the most stressful things to the human body) has only briefly been studied.[4,5] Researchers sought to remedy that by focusing heavily on its relation exercise here.

The Test Group and Variables

Researchers enlisted nine elite weightlifters (21±0.5 years) and had each perform two Olympic weightlifting sessions after consuming either natural pomegranate juice (POMj) in the graphs, or placebo (PLA). To be considered an "elite weightlifter" for the trial subjects had to meet the following criteria:

- Trained at least five sessions per week with 90 to 120 minutes per session,

- Greater than 3 years experience in Olympic weightlifting and,

- No existing injuries injuries and they didn't use any antioxidant (e.g., vitamin A, C, E etc.) or anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) during the experimental period and one month leading up to the trial

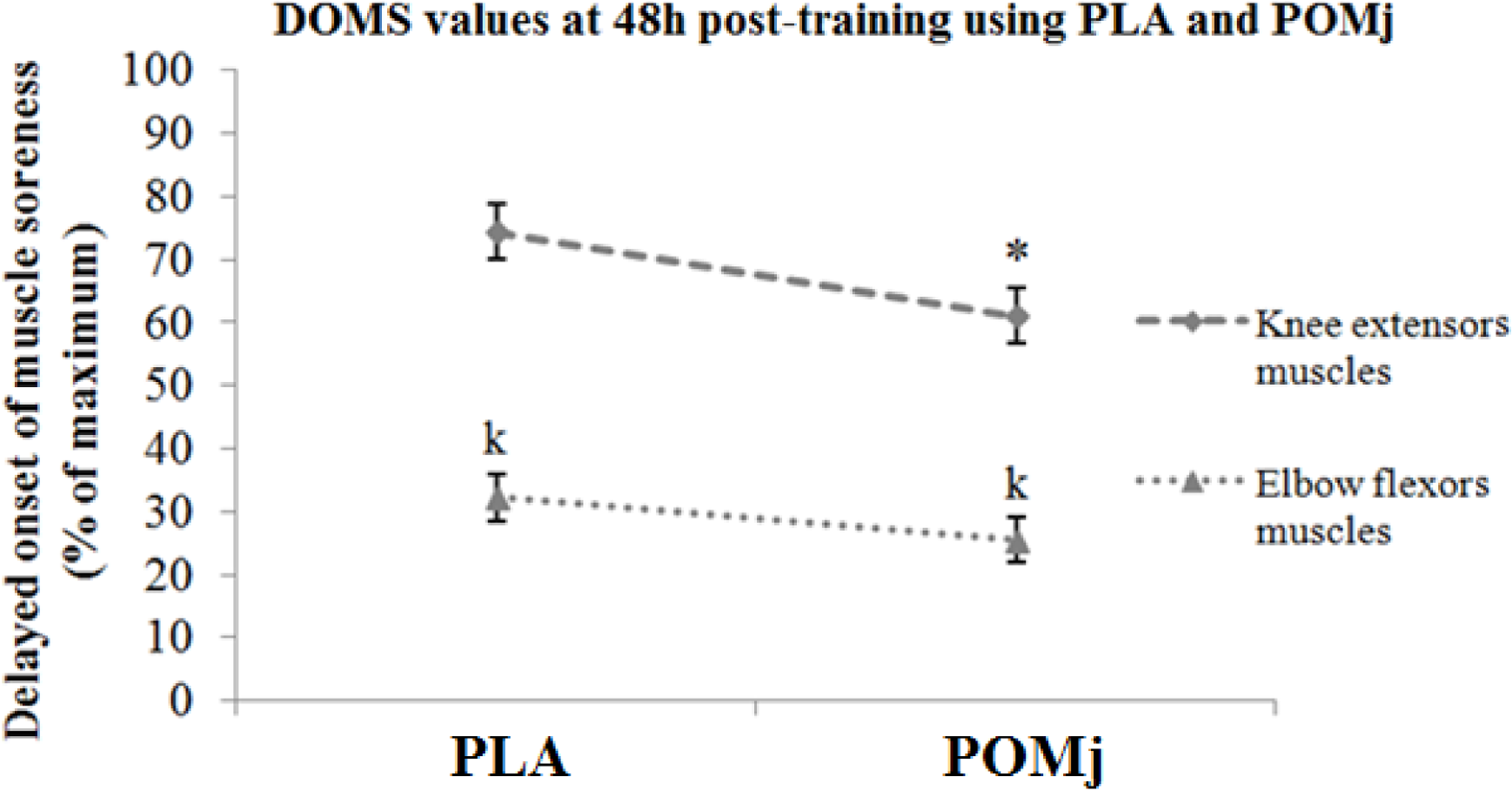

Fig 4. DOMS values using PLA and natural POMj supplementations.

*: Significant differences between PLA and POMj conditions; k: Significant differences between DOMS of knee extensors and DOMS of elbow flexors.[1]

Readings on heart rate, blood pressure and blood samples (hematological parameters, muscle damage and C-reactive protein (CRP)) were collected at rest, 3 minutes and 48 hours following each training bout. In regards to athletic performance metrics, weightlifting performance, Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), and DOMS (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness) were also assessed and recorded after each training session.

Test subjects consumed 1500ml of pomegranate juice three times daily in the 48 hours which proceed the first tested training sessions (i.e. 250ml × 6 times with 8 hour intervals between it). Additionally, during this tested sessions, lifters consumed an additional 500ml of natural pom juice.

What is "Natural" Pomegranate Juice?

We were wondering this same thing, so digging deeper into the study, we came across the answer:

"The tested quantity of the natural POMj was prepared from a fresh pomegranate fruit 48h before the beginning of the experimentation and was frozen and stored at -4°C. No additional chemical products were added to the natural POMj. Each 500-mL of the tested POMj contained 2.56g of total polyphenol, 1.08g of orthodiphenols, 292.59mg of flavonoids and 46.75mg of flavonols."[1]

So the big difference between the juice in the study, and the "wonderful" pom juice you see in stores is the freshness and preservation method of it -- meaning what's used in the study is FAR and AWAY more fresh (meaning more bioactives) than the bottled stuff you'll encounter in the store. We think this may be the reason for some of pom's positive effects on soreness and recovery, which are...

The Results

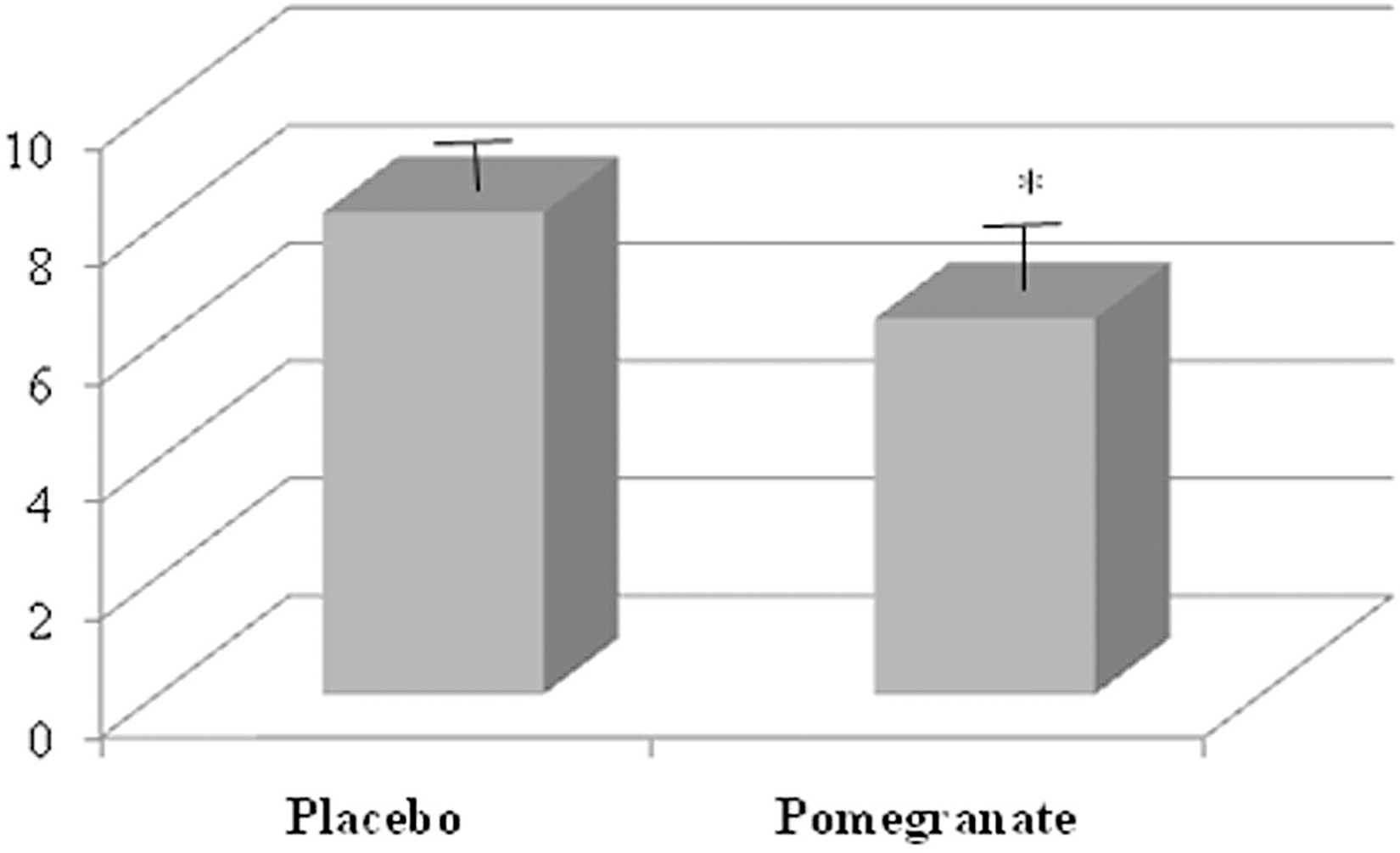

Figure 3 from the study shows that lifters using pomegranate juice had significantly lower RPE than placebo.[1]

The total and the maximal amount of weight lifting in the two Olympic lifts (i.e. the Snatch and Clean & Jerk) during the training session were higher in group consuming pomegranate juice than those consuming the placebo. Based on this, researchers suggest that supplementing with pomegranate juice during the weight training sessions and during the 48 hour following training improves total body strength and "ameliorate the capacity to adhere to intense training program."

Additionally, researchers also documented higher performance (+8.30%) and lower RPE values (-4.37%) using natural pomegranate juice in comparison to placebo. Most importantly though, significant reductions in DOMS of the knee extensors with lower values immediately and 48 hours after the corresponding training session as well as a lower rate of increase in heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure researchers noted in the pomegranate group. Researchers observed 20% reduced creatine kinase (CK) and 15% reduced LDH levels (both indicative of reduced muscle damage) in the test group. Finally the scientists documented lower levels of the liver enzyme AST, which is also an indicator of reduced muscle damage.

Rate of Perceived Exertion

We see this term tossed around an awful lot when discussing various studies, but have you actually taken the time to see what it technically means? Probably not...

Don't worry, we did the heavy lifting and found the precise definition as laid out in the clinical trial application:

RPE scale is a 15-point scale that runs from 6 (very, very light) to 20 (very, very hard). It measures feelings of effort, strain, discomfort, and/or fatigue experienced during physical task.[6] Basically, RPE is a measure of how worn out you get from a particular exercise or activity.

What about POM Wonderful?

Researchers note in the study that the incredibly popular POM Wonderful bottled pomegranate juice was not effective in reducing DOMS or improving recovery.[1] You may need to look for a more potent extract/juice.

In case you didn't catch the reference above, we took a slight jab at POM Wonderful, the leading pomegranate juice on the market. Reason being, it's not as great as it's hyped to be for improving recovery. In fact, POM Wonderful bottle (with a total polyphenol content of 650 mg in each 480-ml bottle[7]), "has no reported effect on muscle damage levels."[1] Yet, the natural pomegranate juice used here contains a whopping 2.56g of polyphenol in each 500ml and showed accelerated muscle damage recovery following intense weight lifting sessions.[1]

Wrapping It Up

This study at hand is more interesting than most of the previously published studies for a number of reasons: First, this trial actually used trained lifters and measured pomegranates effect on recovery parameters following exercise, not just general stress as had previously been studied.

But more importantly, the study measured high-dose pom extract's effect on performance and acute and delayed responses of muscle soreness and biomarkers of muscle damage in response to a weightlifting session, NOT in response to endurance training. No dis to the cyclists out there, but we're tired of seeing endurance studies on cyclists - we want something different. This is important as most recovery supplement studies are conducted following exhaustive endurance exercise such as running, biking, or swimming.

Showing that natural pomegranate juice is beneficial for even the regular lifting crowd means a broader base of appeal and more pertinent to our readership, the "informed lifter."

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)