In a fast-paced, highly-demanding world like ours, it's easy to feel overwhelmed. How can we better cope with the daily stress of modern society?

There are many different approaches, but it's always wise to begin by looking inward – at the human organism – to learn how we can leverage our own design to achieve the physical and mental equilibrium we seek.

The Endocannabinoid System: Our Built-In “Runner’s High”

Vanizem takes stress relief to the next level by boosting anandamide, the "bliss molecule," and supporting your endocannabinoid system. Elevate mood, improve sleep, and protect against chronic stress—all naturally.

When it comes to managing stress, one of the best mechanisms is the endocannabinoid system (ECS). Activating this cluster of cellular receptors can elicit a range of physiological effects, depending on the specific pathways engaged and the context in which they are activated. There are well-known plants that interact with this system, but even if you've never used them, you're likely familiar with the effects of your own endocannabinoids.

That's because endocannabinoids are thought to be involved in runner's high, the feeling of intense euphoria and relaxation experienced after a challenging workout. This boost in mood and cognitive clarity is not merely affective; it can have health implications so profound that you could argue the runner's high may be just as beneficial as the exercise itself.

A large and growing body of research indicates that the activation of the ECS can not only improve mood, but also enhance cardiovascular health, increase pain tolerance, improve sleep, sharpen cognitive function, and reduce appetite.[1] To clarify, according to a 2020 research review on the subject, these benefits are largely independent of physical activity.[1]

Benefits of ECS Activation

While the effects are enhanced when combining ECS activation with exercise, ECS activation alone -- whether through exogenous or endogenous cannabinoids -- can modulate cannabinoid receptors (CB1R and CB2R), endocannabinoids like anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), and enzymes such as fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH). This modulation influences mood regulation, memory, neurogenesis, and neuroprotection. The review further emphasizes that the ECS plays a crucial role in maintaining energy homeostasis, modulating neuroinflammatory responses, and protecting against neurodegenerative processes.[1]

So what's the most effective way to activate the endocannabinoid system? After all, some strategies are better than others, and moderation is key. We need the right intervention, in the right dose – and for that, PLT Health Solutions has pioneered an innovative solution.

Introducing Vanizem – Upregulating Anandamide Endogenously For Brain Health

The supplement is called Vanizem, and for those familiar with the industry, it has an interesting origin. Vanizem is a botanical extract sourced from Aframomum melegueta, commonly known as grains of paradise. What's interesting is that we've extensively covered grains of paradise in another context – fat loss. However, Vanizem was developed to be more consistent with the long ethnobotanical use of the spice, which is to support mood.

Grains of paradise contains vanilloids like 6-paradol that activate the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV-1) receptor. This receptor promotes thermogenesis and increases energy expenditure, supporting fat loss and metabolic health,[2] partly by activating mitochondria within brown adipose tissue, which triggers thermogenesis.[3]

However, the benefits of TRPV-1 activation extend well beyond caloric balance and body composition. This receptor's activity is also linked to neuroprotective[4] and anti-inflammatory[5] effects, increased pain tolerance,[6] improved mood and cognitive function,[7] and enhanced stress resilience.[8]

Does this list sound familiar? It should – these are the same benefits associated with ECS activation!

So, here's the million dollar question: is there a link between grains of paradise and the endocannabinoid system? Absolutely.

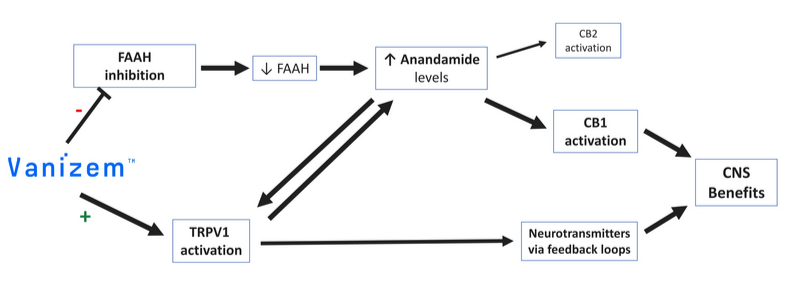

How Vanizem Upregulates Anandamide (AEA), A Key Endocannabinoid

The vanilloids in grains of paradise, of which 6-paradol is one of the most important, inhibit the activity of an enzyme highlighted above – fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH).[9] By downregulating this enzyme, Vanizem effectively upregulates an important endocannabinoid called anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine, or AEA). Anandamide is named from the Sanskrit word "ananda", meaning bliss. It was the first endocannabinoid to be discovered and elucidated,[10] and is connected to the anxiety-reducing effects of FAAH inhibition.[11]

However, vanilloids are volatile constituents that must be protected against destruction from environmental factors like heat and oxygen, as well as from stomach acids. Vanizem was developed using proprietary microencapsulation technology, which provides superior properties, including improved stability over time and at high temperatures, greater efficacy, versatility in formulation, water dispersibility, and preservation of volatile compounds like the vanilloids to which it is standardized. This patent-pending process minimizes the loss of bioactive compounds and ensures the integrity of our final product, preserving its nutraceutical value and efficacy at a low dose.

The patent-pending microencapsulation is achieved through complex coacervation (the separation of two liquid phases in colloidal systems). An emulsion is made of Aframomum extract with Gum Arabic, then pea protein and low methoxyl pectin are added. The pH is adjusted to form the coacervates, the product is spray-dried, and the final extract becomes Vanizem. The effects of Vanizem on the endocannabinoid system are unique and have not been clinically demonstrated for any other extract of grains of paradise.

Anandamide is, among other things, a TRPV-1 agonist – and as we'll see, it's one of the most important molecules for both brain health and overall health. Interestingly, AEA activates TRPV-1, but TRPV-1 activation also upregulates AEA – a rare example of positive feedback in neural biochemistry. It seems that the human brain is particularly fond of TRPV1 and AEA.

The bioactive constituents activate TRPV1 directly, but also indirectly through FAAH inhibition and anandamide upregulation.

-

Analgesic

After anandamide was discovered in 1992, its analgesic properties were quickly recognized,[12] with studies showing that it can modulate pain and increase pain tolerance both during and after exercise.[13-21] This is linked to the well-known "runner's high", where endocannabinoids, including AEA, help alleviate the discomfort of physical exertion.[22]

One study from 2010 found that when AEA levels are artificially elevated through the administration of a drug that inhibits AEA breakdown, animals exhibit a significantly reduced response to pain.[23]

-

Mood booster

In addition to its analgesic properties, anandamide shows promise in supporting mood. Preclinical research revealed that AEA could reverse melancholy behaviors, possibly by restoring critical neurotransmitters like serotonin, often referred to as the "happy hormone".[24] As you will see below, Vanizem, which upregulates anandamide, has been clinically shown to improve mood.

-

Antioxidant

Additionally, anandamide was found to restore levels of glutathione and superoxide dismutase, both of which are crucial in combating oxidative stress -- a factor linked to chronic inflammation and low mood states and.[24]

-

Improves sleep

AEA also plays a crucial role in sleep regulation. It enhances sleep quality by upregulating adenosine, a compound that promotes sleep onset and counteracts the effects of stimulants like caffeine.[25] Additional animal research demonstrated that anandamide increased time spent in slow-wave sleep, the most restorative sleep stage, by acting on the cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1).[25,26] As discussed below, Vanizem, which upregulates anandamide, has been clinically shown to improve sleep.

-

Anti-inflammatory

In addition, AEA exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effects. It's been shown to significantly reduce inflammation and improve lung function in mice suffering from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a severe inflammatory condition. By altering gene expression involved in the inflammatory response, anandamide nearly restored the mice to normal health.[27] It also reduced social deficits in rats with inflammation-induced behavioral changes, suggesting it could help treat a range of conditions linked to inflammation.[28]

-

Cardioprotective

Anandamide appears to also trigger vasodilation in abdominal vasculature[29] and in the pulmonary arteries,[30] mechanisms that can lead to a substantial reduction in blood pressure.[31] While studies specifically addressing AEA's ability to induce systemic inflammation are currently lacking, a review of the existing literature strongly suggests that it can.

Interestingly, the body seems to use anandamide as a type of endogenous blood pressure regulator – patients with obstructive sleep apnea, which is known to raise blood pressure, have higher serum levels of endocannabinoids compared to non-apneatic obese individuals.[32]

Activates TRPV-1

The effects of TRPV-1 and AEA are closely intertwined because, as mentioned earlier, each one upregulates the other. However, TRPV-1 also exerts effects that are independent of its interaction with AEA.

One significant benefit of TRPV-1 activation is its role in pain modulation. When activated by heat or capsaicin (the compound that gives chili peppers their spiciness), TRPV-1 channels in sensory neurons open, leading to an influx of calcium and sodium ions.[33] This triggers the release of neuropeptides like substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which play crucial roles in transmitting pain signals to the brain.[34] While this initially enhances pain perception, prolonged activation of TRPV-1 can lead to desensitization, reducing pain over time. High concentrations of TRPV-1 agonists like capsaicin can lead to long-term desensitization, a mechanism utilized in topical pain relief treatments that incorporate capsaicin.[35]

New Vanizem Pilot Research

While much is known about Vanizem's mechanism of action, particularly AEA upregulation via FAAH inhibition, the clinical effects of Vanizem are only just beginning to be explored. PricePlow has obtained pre-publication data on a brand new clinical trial of Vanizem and is pleased to share the preliminary results with you here.

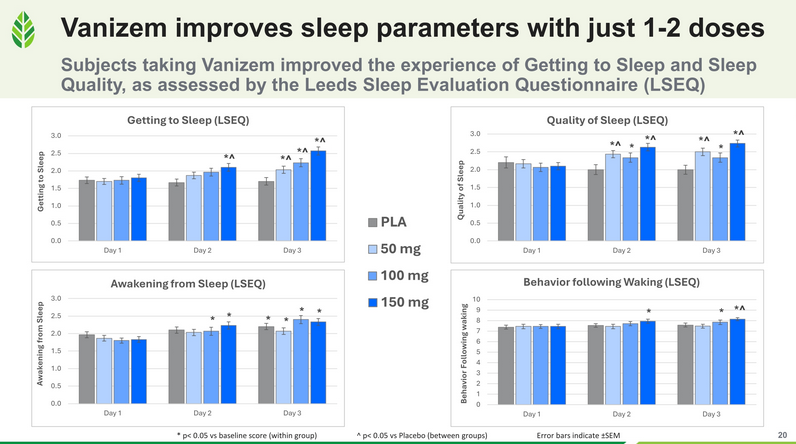

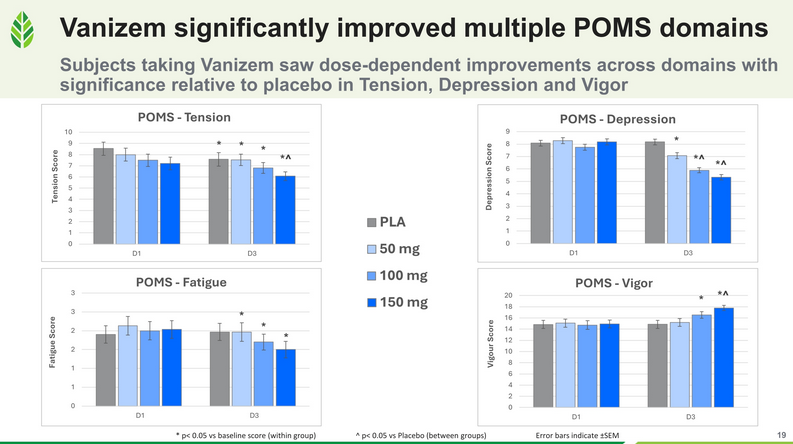

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, crossover clinical trial, 30 healthy women and men with mild anxiety received one of three doses of Vanizem (150 mg/d, 100 mg/d, or 50 mg/d) or a matching placebo for three days. Evaluations included the Profile of Mood States (POMS), Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (LSEQ), heart rate variability (for side effects monitoring), and a modified Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (mHAMA). While all subjects improved relative to baseline, those taking Vanizem demonstrated dose-dependent improvements in Total Mood Disturbances, with the most statistically and clinically significant effects observed at 150 mg/day and 100 mg/day.

The impact of Vanizem on individual subsets of the POMS Total Mood Disturbance score (Tension, Depression, Fatigue, and Vigor) is shown in the graphic below.

The Profile of Mood States (POMS) is a psychological assessment tool that measures an individual's mood states across six dimensions: tension, depression, anger, vigor, fatigue, and confusion.[36] This tool is commonly used in research and clinical settings to evaluate mood fluctuations and emotional well-being.

Vanizem significantly increased key dimensions of sleep, like getting to sleep and quality of sleep.

Vanizem also significantly improved crucial aspects of sleep. Specifically, the study observed large effect sizes in the high-dose groups for both sleep onset and sleep quality after just 1-2 doses.

Sleep impairment triggers a cascade of negative effects — each amplifying the other — leading to a negative feedback loop declining mental and physical health that becomes increasingly difficult to reverse. As sleep deprivation persists, the body's stress response intensifies, with elevated cortisol levels making it harder to relax and fall asleep. The lack of restorative sleep impairs cognitive function, resulting in memory issues, decreased problem-solving abilities, and a reduced capacity to manage emotions. This mental decline can contribute numerous health consequences and terrible mood states, further deepening the cycle of stress and sleep disruption.

In other words, improving sleep quality in a safe, non-addictive way is crucial for achieving all of the stated goals of Vanizem supplementation. It's very encouraging to see that Vanizem has this effect.

Vanizem: An Exciting Way to Naturally Boost the Endocannabinoid System

As our understanding of the endocannabinoid system deepens, it's becoming clear that working with it offers the potential for profound mental and physical benefits. Far from just creating a "runner's high", the ECS plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis, regulating mood, cognitive function, and sleep, while also providing neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory effects.

Unlike other stress management approaches that focus on a single aspect of health, endocannabinoids offer a holistic solution by engaging multiple pathways simultaneously. The ability of endocannabinoids to provide the benefits described above offers an all-encompassing defense against the damaging effects of chronic stress.

Vanizem, which leverages the ECS by upregulating anandamide, can naturally enhance the body's internal stress management mechanisms, offering a safer, effective way to break the cycle of stress and declining health.

We're waiting for more data on this very promising ingredient – stay tuned to the PricePlow Blog for more information -- this article will be updated as the body of research grows.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)