We’ve come a long way these past few years in the sports nutrition corner of the supplement industry. Thanks to the two visioneers who run Revive MD — Dr. Domenic Iacovone and Matt Jansen — health support supplements have been made cool again. Not only that, they’ve been made efficacious, with massively packed formulas to support your health and wellness goals.

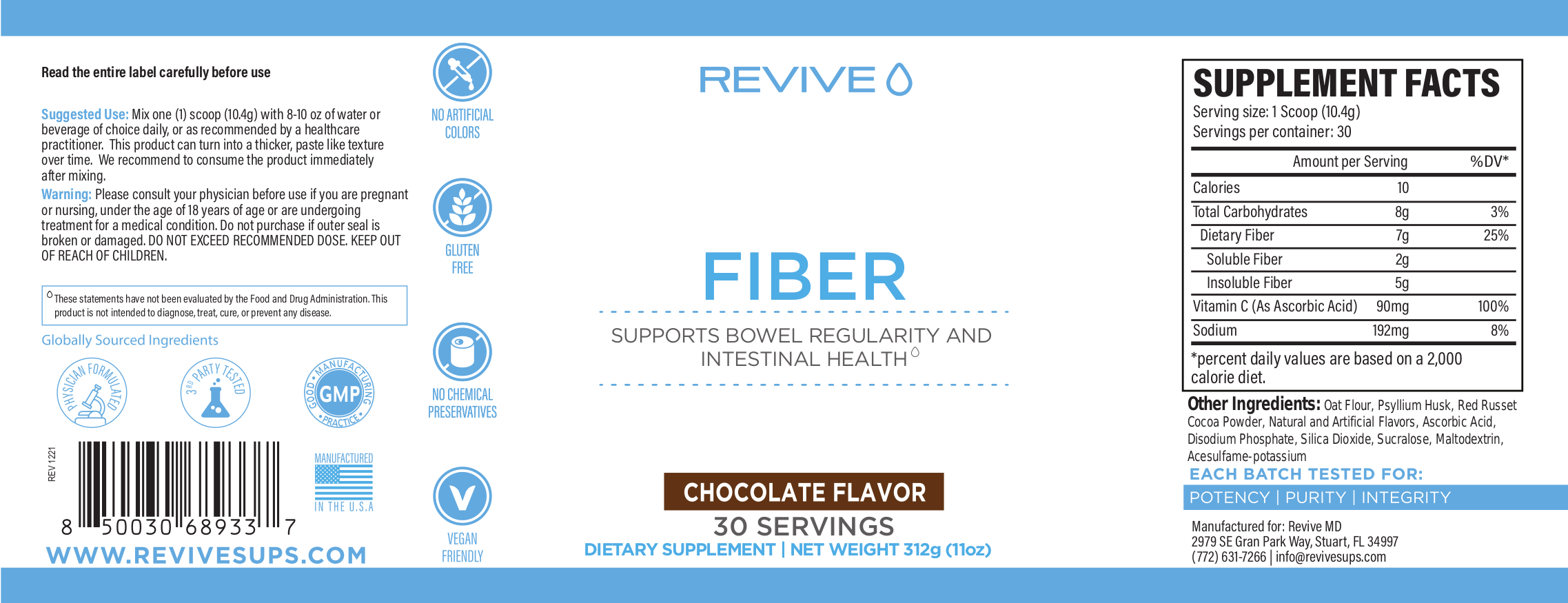

Introducing Revive MD Fiber, which has both soluble and insoluble fiber, and comes in a delicious chocolate flavor!

We recently covered their digestive enzyme blend in Digest Aid, which could be used to support their GI+ gut health supplement alongside Revive MD Glutamine. One key part of this gut and digestive health puzzle was missing, though: Fiber.

Revive MD Fiber: A Unique Fiber Blend

This week, the team introduced Revive MD Fiber, a new fiber blend that gives its users 7 grams of dietary fiber per serving. This supplement was designed to support bowel motility and healthy intestinal function. Even better, it was released in both an unflavored and chocolate flavor!

What’s unique about it, on top of having a chocolate flavor available? It’s using oat fiber alongside the psyllium husk.

We dig into the formula below, but first, see PricePlow’s Revive MD News alerts, as they’ve just been named our 2021 Breakout Brand of the Year alongside Raw Nutrition, and we expect tons more this year:

Revive MD Fiber – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

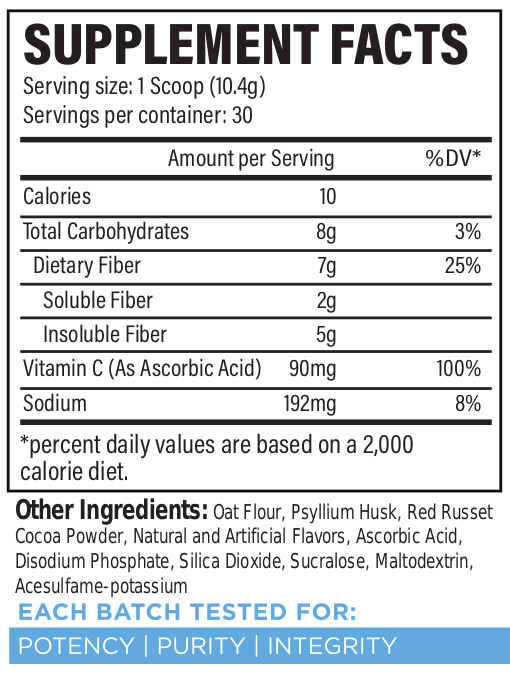

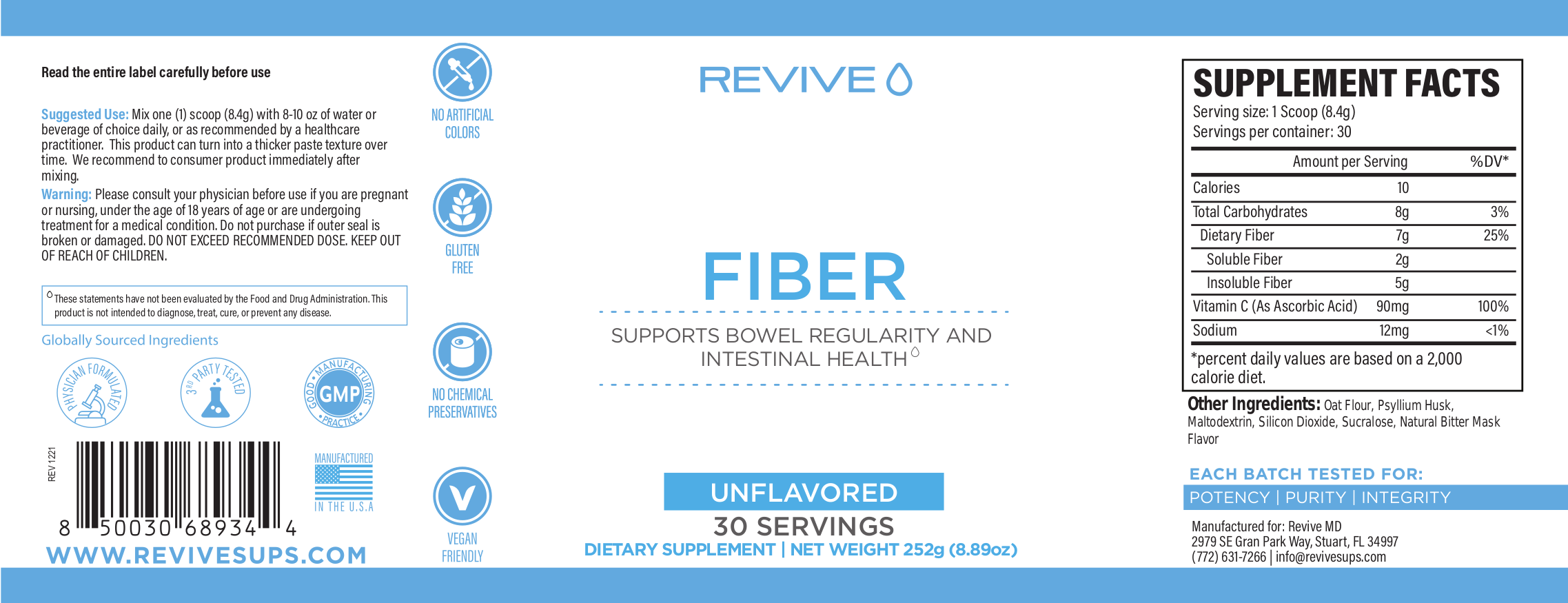

Revive MD Fiber Nutrition Facts / Macros

Each scoop of Revive Fiber yields the following:

-

Calories: 10

-

Total Carbohydrates: 8g

-

Dietary Fiber: 7g

-

Soluble Fiber: 2g

-

Insoluble Fiber: 5g

-

-

There’s also a 100% DV (90 milligram) dose of Vitamin C from ascorbic acid.

Why Fiber?

Fiber is an incredibly important type of carbohydrate that’s generally defined by molecular composition and non-digestibility.[1] There are many types, but they’re most often broken down into two forms:[2]

- Soluble fiber – Often found in fruits and vegetables

- Insoluble fiber – Often found in cereals and whole-grain products

Most fiber-containing foods contain blends of fiber, and the gastrointestinal tract tends to ferment soluble fiber faster than insoluble fiber.[2]

Fiber recommendations differ depending on your type of diet and who you ask, but for carbohydrate-based dieters, the general recommendation is for men to get 30-35 grams per day and women 25-32 grams per day.[3]

The benefits of fiber

We’ll briefly gloss over the benefits of fiber, but for a more detailed read, the 2020 article recently published in Nutrients titled “The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre” has a great modern overview, which cites not just standalone studies, but numerous meta-analyses also cited below:[4]

- Gut motility and constipation prevention[5]

- Body weight and abdominal body fat improvements[6,7]

- Insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health improvements[8]

- Healthier gut microflora environment[9]

- Reduced inflammation[10,11]

- A minor improvement in mood[12]

- Lower rates of cardiovascular disease[13,14]

- Reduced risk of colorectal carcinoma[15,16]

- Lower overall mortality[17]

Each of the studies cited above looks at various mechanisms, but most of them seem to be downstream of the fact that fiber helps the gut ferment short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs),[18,19] which have incredible benefits ranging from anti-inflammatory activity[20] to a heart-protective reduction in TMAO (Trimethylamine-N-oxide).[21]

The point being this: if you’re on a moderate or high-carbohydrate diet, you’re wise to keep fiber in the diet,[4] and getting nearly 30 grams per day is no easy feat. That’s where Revive MD Fiber can help:

Revive MD Fiber Ingredients

Two primary ingredients to discuss – oat flour and psyllium husk — and then we’ll discuss the other ingredients, because even the unflavored version has some sweetener added!

-

Oat Flour (from oat hull fiber)

We don’t often see this one in fiber supplements, but it makes a great deal of sense. Diverging from using psyllium husk alone, Revive MD adds a large dose of oat flour to the blend, which not only adds fiber, but some unique non-carbohydrate components.

Oat hull fiber: a highly insoluble fiber that provides some glycemic benefits

We’ve received confirmation from CEO Matt Jansen that it’s actually the oat hull fiber component, which is how the macronutrients stay low in active carbs. Oat hull fiber is a highly-insoluble fiber[22-24] (as much as 95% insoluble[24]), and is a lesser-fermented fiber than psyllium[22] — which comes next in the formula. This is going to give us the best of both worlds, providing both soluble and insoluble fibers when most fiber supplements usually just have one or the other.

Oat hull fiber has been shown to have a minor HbA1c-lowering effect in women,[23,25] who had modest glycemia improvements. Additional data shows that those improvements are most significant for those who have impaired fasting glucose.[23,26]

Other benefits of oats

Important to note that Revive is using oat hull fiber, not the entire oat – so the active carbs won’t be high

Beyond the specifics of oat hulls, oats are also well-known for their additional key vitamins, minerals, and bioactive plant nutrients like β-glucans that provide metabolically protective benefits.[27,28] That the scientific community is becoming increasingly aware of β-glucans ability to alter blood cholesterol levels,[27,28] an effect many see when increasing oat or fiber consumption. The beta-glucans inside may be the reason for that.

If lipid levels are a concern, you should also consider Revive MD Lipid in your stack. We always point out, however, that our primary focus is on HDL and triglyceride levels, as those are two more significant biomarkers for insulin sensitivity and metabolic health. But for high-carb dieters who do have elevated triglyceride levels, fiber may be used to help balance total cholesterol in your favor.

Additionally, oats possess unique polyphenols known as avenanthramides, which have nitric oxide boosting properties that also provide anti-inflammatory and anti-itch benefits![29,30]

-

Psyllium Husk

Also known as Plantago ovata, Plantago psyllium has fibrous husks that supplement users are familiar with: psyllium husk fiber. This is one of the key ingredients used for decades in diary fiber supplements, and for good reason – there’s a wealth of information and research on it!

Psyllium husk fiber primarily consists of a polymer named arabinoxylan, which is composed of arabinose and xylose, which the human digestive system won’t sufficiently digest.[31] As opposed to our oat hull fiber, psyllium is highly water soluble – it actually forms a gel when mixed with water, and is slow-fermenting.[22,32,33]

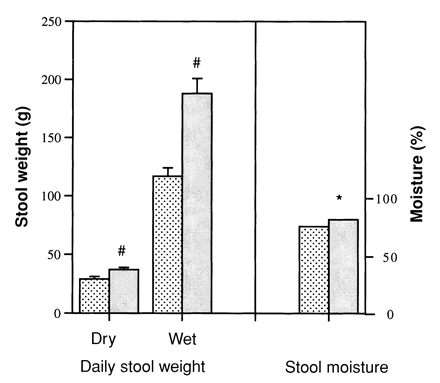

Increased stool weight – a bulk laxative

For decades, psyllium has been used as a laxative,[34] but not just any type of laxative. It works primarily by increasing fecal weight and stool size[34-37] thanks to its combination with gas and water in the colon and small intestine.[38] This function is extremely versatile, because it can both solidify stool for those who are too soft, but soften it for those whose are too hard![39] Ultimately, it leads to easier to pass, softer stool,[40-42] yet helps reduce diarrhea as opposed to causing it.[39]

All in all, psyllium husk’s versatility makes it an incredibly popular dietary fiber to be supplemented. It turns out that if you take enough of it, there are additional benefits to be had:

Reduced gas

One study using intrarectal catheters on humans who were healthy showed that they actually had less gas when taking a massive 30 gram dose of psyllium.[43] Often, we think of fiber supplements as doing the opposite, so realize that psyllium is not like those other fibers in this and many other aspects.

There are also some interesting diet-related benefits:

Appetite reduction

Revive MD, a supplement brand that’s no stranger to all-in-one formulas, has put out their comprehensive GI Health supplement, GI+

Research has shown that psyllium husk can consistently reduce appetite, especially 3-6 hours after ingesting enough of it.[44-46] Those are larger doses — between 10 and 20 grams worth — so you’d need to take a few scoops of Revive MD Fiber to get those effects. It’s a nice effect, but there are definitely better ways to reduce appetite, such as removing processed foods that make you hungry, such as sugar and endocannabinoid-activating omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids found in vegetable/seed oils. Still, it’s a great tool to have in the toolkit.

Reduced blood glucose levels, HbA1c, and lipids

Test subjects who use psyllium husk fiber have consistently shown reduced blood sugar levels,[47-49] and unlike some of the studies cited above that used massive doses, one was effective with as little as 5 grams three times daily.[48] In addition, every lipid value improved, including a boost in HDL while reducing triglycerides,[48] which is indicative of improved insulin sensitivity as mentioned above in the oat section.

Additionally, one study showed that a 14 gram dose of psyllium husk lowered glucose absorption by 12%,[47] and another one had lowered blood sugar levels.[49] Consistent with research on fiber in general, we can conclude that those who are insulin resistant or concerned over glycemia are wise to consider supplementing psyllium husk.

An interesting, cholesterol-consuming mechanism

How does it work? It seems that psyllium husk fiber actually binds to bile acids, and that subsequently forces the body to produce more of them in an effort to maintain homeostasis![50] This process consumes cholesterol, leading to the reduced cholesterol plasma levels seen in psyllium husk users.

While this happens, we get some beneficial short-chain fatty acids produced during the slow fermentation process as well.[50]

-

The other ingredients

In the other ingredients section, you’ll see something interesting: sucralose! Even in the unflavored powder, it’s still sweetened so that it’s more palatable than your average fiber supplement.

In addition, there’s some maltodextrin added, but don’t fret if you’re concerned about it spiking blood sugar levels – if you look at the chocolate flavor, you’ll notice how far down the maltodextrin is buried (it’s behind sucralose there and the macros are the same as the unflavored version), so we’re unconcerned about it doing much besides assisting with consistency.

The chocolate flavor also has some acesulfame potassium (“ace-k”) at the end, and of course cocoa and other flavors.

Dosage and Instructions

Per the label, use one scoop with 8-10 ounces of water daily, or as recommended by your doctor. If you let it sit too long, the psyllium husk will gradually absorb water and become more gel-like, so get it down sooner than later and let the husk do its work in your body, not in your shaker cup.

Flavors available

Just in case Revive MD comes out with other flavors, they’ll be listed below:

A fiber supplement with both soluble and insoluble forms that’s enjoyable

This honestly shouldn’t be anything that earth-shattering, but here we are in 2022, and we finally have a dietary fiber supplement that brings two worlds together. Far too often, dietary supplements have only relied on soluble fibers like psyllium husk. And while those are great, there’s something to be said about the added benefits of blending in an insoluble fiber as well.

Oat hull fiber makes a tremendous addition, given its extremely high insoluble fiber content, providing a more “broad spectrum” for Revive MD users. All the better that we have a chocolate option too!

You can consider this the latest member of the Revive MD Gut Health, which also includes GI+, Digest Aid, and Revive MD Glutamine. Do you need them all? That depends on your situation – some readers just need more fiber to go along with all of those non-fibrous carbohydrates. But if your gut is in a bind, then take a look at the stack above and see how the month treats you. The proof will be in the pudding!!!

Revive MD Fiber – Deals and Price Drop Alerts

Get Price Alerts

No spam, no scams.

Disclosure: PricePlow relies on pricing from stores with which we have a business relationship. We work hard to keep pricing current, but you may find a better offer.

Posts are sponsored in part by the retailers and/or brands listed on this page.

Comments and Discussion (Powered by the PricePlow Forum)